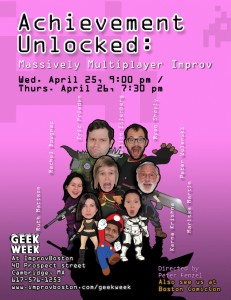

Achievement Unlocked: Massively Multiplayer Improv, a comedy show starring the talented team Elephant in the Room (including Overthinking It TFT podcast mainstays Sheely and Cognac, and longtime friend of the Overthinking It crew Eric Frieden), premiered this past Sunday at Boston ComicCon to a packed house. Before we head into the rest of our run at ImprovBoston’s Geek Week (where you can also see Overthinking It Live and hopefully a live recording of our 200th podcast), I figured I’d run down some of the artistic thinking behind the show, especially because it involved subjecting a segment of our popular culture to a greater level of scrutiny than desert might dictate.

The Starting Point

So, in the beginning, I was approached by Ruth and Sheely from Elephant in the Room to advise on and potentially direct a video-game themed comedy show. I had just organized and presented a workshop on comedy show concepting with some very interesting guests and conversations, so we tackled the first two questions at hand:

- What is the core funny/interesting thing that makes me want to do this show?

- What medium is best-suited for translating it?

These questions were interesting enough for me with regards to video games that I signed on to direct the project. But before we address them, let’s tackle a question I see entirely too often:

Are Video Games Art?

Of course video games are art – even if they don’t match a given formal definition of art exactly, they share all the essential qualities of other media that are definitely art – or, rather, they match the qualities of other media through which art is presented. They are capable of generating emotional responses, aspiring to and achieving beauty, imitating life, perfecting on imperfect ideas and forms, creating semiotic ambiguities and unities, and, if such a thing is possible, reaching toward Truths. Whatever your philosophy of aesthetics or the value of artistic work, there is something for you in video games.

Maybe what people are discussing when they discuss whether video games are art is whether they are “good enough” art to deserve the title. And for that, well, as I’ve written on this blog before, I’ve never been a huge fan of that question, because there is no accounting for taste, and because almost all art that is very good is totally shitty up until the point where the general public is allowed to see it.

Anyway, I see the art of video games as breaking down into several categories:

- The discrete, conventional art that supplements the game – things like cutscenes, visual tableaux, images and animations, music – stuff that if you pulled it out of the video game and set it aside, it would still be art. This stuff is art the way music or movies are art.

- The art involved in bringing the game into being – things like the elegance of the code, the way the physics engine is incorporated, the way the designers and developers find inspiring ways around problems. This stuff is art the way chess is art, or design, from woodworking to architecture to electronics. The art isn’t just in how the thing is perceived or experienced, there is also art in how it is created and how it works.

- The experiential art of the game as it is played – things like Mario jumping on a Goomba as a performative act – or even the player pushing the button prompting Mario to jump, and how that has aesthetics, norms, tropes, a fourth wall, and many other elements that are present in a live theater performance. This stuff is a performance art, like when an audience watches a singer sing a song live.

An Act of Translation

There are lots of comedy shows that focus on the first of these classifications, taking the various symbols and tropes and discrete art objects of gaming and other geek culture and referencing them or putting them in the context of a traditional western comedy show. The Big Bang Theory is a good example – it dresses itself up in the recognizable discrete art objects of geek culture, but its structure is thoroughly sitcom-ish. An episode of The Big Bang Theory might talk about Ms. Pac Man, but at no point does it resemble playing Ms. Pac Man.

“Well, of course it doesn’t, it’s a TV show, not a video game,” you might say.

But, looking at the third classification – the experiential art of the game as it as played – just as a poem originally written in Spanish might be translated to English, a player-game experience in a video game might be translated into a performer-audience experience in a comedy show. And it would also be fun to poke fun at this relationship, to explore it and find out some funny truths about it, by pulling it out of context and looking at it from another angle.

For this to work, we need to get away from the idea of “literal” translation. We don’t want to literally hook up wires to the actors and have audience members play them. We also aren’t playing You Don’t Know Jack or The Secret of Monkey Island, where the game itself is a comedy show. We have very little budget, a real-life team, and want to get across our idea with fairly traditional theater resources.

So, just as translating the poem in Spanish isn’t really about a “literal translation” – literal translations tend to totally fail at accomplishing what the piece they are translating are trying to accomplish. It’s like redesigning a car model into a boat and giving it wheels instead of propellers. No, we want to pick the elements that work and translate analogously.

Viva La Rasa

One thing to keep in mind is that the relationship between the audience and the performers in a live stage piece is not fixed. It is very easy to think they are, because of how devoted to them Western artistic discussions tend to be, but even in the West, different sorts of theater or movies or what have you build the relationship between the audience and the performers in very different ways. The fourth wall, the idea of playing a “character,” the idea of having a “hero,” the idea of telling a “story” – despite classes and guidebooks to the contrary, all these things are negotiable.

Perhaps no performance style brings this out more clearly to me than traditional Indian theater of the Natyasastra, specifically the eight-eleven rasas (“juices,” “flavors” or “essences”), give or take, depending on the tradition, and how they work practically in engaging an audience throughout Indian tradition.

Now, bear with me, because I am not an expert, but my sense for the rasa is that they are emotional states that a performative work aims to inspire in an audience. Far from Western performance traditions, where the reaction from the audience is external to the work itself and a result of it, the rasa are integral to the work – they are presided over by specific divine personages who then preside over the performative acts, and having onlookers experience the specific rasa is essential to executing the piece (as compared to Method, where it is far more important for the actor to experience the emotional life of the piece, and audience reaction is something left up to the relative success of the play with which the artists cannot be all that concerned while they are performing it).

Here is an example of a dance performance that is based on Sringara rasa, the essence of attraction, erotic love and beauty:

Note the number of hand signals, indications, and representational tableaux that are thrown into the piece to signify different elements that as a whole mean to evoke and conjure the emotional reaction from the audience. This is a very unnatural and nonrepresentational series of actions, but the reaction they are meant to provoke is very familiar and thousands of years old – in turn showing that an authentic experience from an actor is not necessary for an authentic experience from an audience, and that the completion of the artistic act doesn’t always occur on the far side of the proscenium.

(This tradition, by the way, cuts across Indian performance arts and is one of the reasons why Bollywood movies seem unnatural by Western standards.)

The Qualities of Video Game Experience

So, what qualities of the video game performing arts experience did I want to “translate” to the stage?

Participation – I didn’t want the audience to feel passively engaged, watching a presentation that was being given to them. As charming as it is, The Super Mario Brothers Super Show is not Super Mario Bros. I wanted the audience to feel involved with the action onstage and be able to participate in what happens.

Conflict that breaks the fourth wall – I didn’t want to represent conflicts to the audience, appealing to their sympathy to root for a hero. I wanted conflict depicted onstage to involve the audience as one of the parties involved, and for them to see the heroes as extensions of themselves. This led to me wanting more of the conflict to be external to the characters, with actors conflicting with others actors, but from the structure of the show itself.

Identity creation – In the table work we did developing the show, talking about what we liked or didn’t like about video games, the major theme that jumped out from everyone in the group was the ability to create or choose avatars or representations of themselves. The less involved with video games the players were, the more they admired the powers and capabilities of a video game character, and the more involved with video games the players were, the more they saw building or choosing a character as validation of themselves. But it was important for the audience to be able to define a transformative avatar of some sort to feel invested the way they are invested in video games.

External rewards and praise – This was something I wanted to make fun of a bit in the show, as well as the inspiration for the show’s name, how video games create overarching realities that deliver, as manna from the heavens, praise and validation, often for random and undeserved things (ACHIEVEMENT UNLOCKED: BIBLICAL REFERENCE!!! COMBO! BONUS!!!).

Escalation and Culmination – Video games have functional climaxes. They may not match up well with a rising action, moment of recognition, or other qualities of plot arcs in other media, but there is almost always some sort of high point that brings the gaming experience to an apotheosis – even if it is just to get the high score or to get past the pretzel on Pac Man; in games where culminations are weakly justified, we as players are willing to amp up the importance of the culmination in our own minds to compensation.

In particular I think of Clu Clu Land, a game that resembles a personal hell of unending, awkward and increasingly heinous challenges, but which I enjoyed a great deal and still felt like I won from time to time, especially when I made a cool cool picture and everything flashed:

None of these things, I feel, are present in scripted theater without heavy use of gimmick that can’t be repeated easily and doesn’t have much space to explore, like The Mystery of Edwin Drood. They aren’t even all that prevalent in sketch comedy or long-form improv. So, after considering the elements that we wanted to translate, I decided that about half the show would be short-form improv – that is, stuff like Whose Line is it Anyway or Wild ‘N Out.

(By the way, here I am going to post a bunch of out-of-context Wild ‘N Out games, which come without explanation, mostly because they show how the forms can be adapted to different crowds and the relationship between the performers, guests and audience, which is very different from most other kinds of Western theater. And also because a surprising number of people have never seen Wild ‘N Out. Warning for uncouth language and the presence of Mariah Carey’s husband.)

With short-form improv, the audience or the host sets external expectations for the performers, giving them challenges and information, and then watching them succeed or fail to meet the demands of given games. Also, there are many games where audiences members get to come onstage and participate in various not-very demanding ways.

So, knowing that the escalation and culmination of video games is not necessarily something that follows a plot, but is more functional than syntactical, like how it is in music, we workshopped and crafted an overall show design that linked the short-form games with long form elements (“grinding”), where the players explored the traits and customization given to them by the audience in the avatar creation games. It was designed to recall a variety of different video game forms and styles, but mostly fantasy games, both traditional RPGs and MMORPGs.

The choice of form might seem trivial (oh, you did short-form improv? You could have just done sketch comedy.), and it is one often done too hastily in my opinion, but by the end we built a composition that I think in the end is mostly a short-form improv show, but that has a structure and a point and succeeds in translating the artistic core of the video game experience that interested me at the start of the project.

Come see Achievement Unlocked at ImprovBoston’s Geek Week, this Wednesday & Thursday, in the 9:00 p.m. Eastern and 7:30 p.m. Eastern blocks respectively. If it does well and people like it, we may look for further opportunities for the show.

Any thoughts about the artistic core of video games, the relationship between performer and audience, or the career of Nick Cannon? Halftime is Game time! Sound off in the comments!