It is that time of year when, in observance of the holy days of Easter and Passover, the pop culturally devout choose yet again to watch one of the greatest movies of all time, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments.

DeMille notes in the opening credits to the movie that it draws on many sources, including the books Prince of Egypt by Dorothy Clarke Wilson, Pillar of Fire, by the Reverend J. H. Ingraham, and On Eagle’s Wings, by A.E. Southon. But for those who internalize its gravitas and epic spell of persuasion, I wanted to point out some key things that differ specifically between The Ten Commandments and the Biblical Exodus account. Pull up an empty chair, hide some eggs and bread, and let my people go!

10. Moses is a badass Egyptian military commander.

Decades before Stanley Tucci’s raw charisma and contagious enthusiasm made us all complicit to the child-murder of The Hunger Games, The Ten Commandments condemned a decadent, amoral, totalitarian dictatorship by showing us how fabulous everybody’s clothes were. Sure, the Moses of the Bible was adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter and raised in a high social station, but the Moses of The Ten Commandments is a certifiable Big Man On the Nile — a war hero and statesman, who defeated the Nubians in battle in Ethopia and signed them into an enduring alliance with Egypt shortly before the whole thing with meeting God and moving the ocean.

A towering presence in court, at 6’2” with a perfect tan, chiseled features and his own Egypt is Awesome golden hat, Heston has the cache and the backstory to be a real Biblical hero, even though the actual heroes in the Bible tend less toward “Conqueror of Africa” and more toward “Wandering Bipolar Homeless Guy.” Don’t worry; he gets there.

Planet of the Egyptians.

9. There are a ton of minor characters with serious, but arbitrary names.

The Torah is a document of the very distant past, and as such it does not retain a great deal of specificity of the day-to-day goings on in the lives of early Biblical figures. In the alphabet soup of begetting generations, it is easy to forget than the ten or twenty names in a row are the only names we know over centuries or millennia of Biblican Time. The Biblical story of Moses is full of people like “Pharaoh’s Daughter,” “two fighting Hebrews,” or “the elders of Israel” without being all “Hey Ron! How goes it?”

Of course, this would not do in the film depiction, where people know what to call each other as they go about the business of Exoding. So, The Ten Commandments gives people names — but it is not enough to just give people names – with grand handles like Yohcabel, Memnet, Sephora, Jannes, Pentaur, Abiram, Eleazar and Korah, it is difficult to tell which characters are actually from the Bible (hint: about half of them). But it sure does sound majestic and Pentateuchial!

I mean, just check out these opening credits (and the entire movie after them, if you’ve got 4 hours to spare, on YouTube license):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oy1K3JBz1DQ

8. Moses is also a progressive labor agitator.

Moses: No son could have more love for you than I.

Sethi: Then why are you forcing me to destroy you? What evil has done this to you?

Moses: The evil that men should turn their brothers into beasts of burden, to be stripped of spirit, and hope, and strength — only because they are of another race, another creed. If there is a god, he did not mean this to be so.

Seven years after the release of The Ten Commandments, Charlton Heston would participate in the A. Philip Randolph’s “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” the massive Civil Rights rally where a then-relatively-less-famous guy named Martin Luther King, Jr. would offer a very memorable speech about having a dream, and a then-relatively-much-less-famous guy named Robert Zimmerman who went by Bob would play some guitar.

In the meantime, The Ten Commandments, despite its obviously traditional subject matter, contains quite a bit of progressive economics. Moses, in a position of authority over the Hebrews, introduces reforms in Egypt. He increases their rice rations and gives them the Sabbath day off less as a divine command and more as an improvement to their standard of living. He is offended by the racism and prejudice of the Egyptians, and calls upon them to be fair-minded, to treat workers well, and to deal equally with all peoples.

When Pharaoh demands the Hebrews continue to make bricks without their deliveries of straw, Moses calls for a general strike (of slaves, ‘natch), daring Pharaoh to make a city without bricks. In the Bible, Pharaoh makes a similar demand, but Moses does not confront Pharaoh over it, he turns to God, because the Hebrews are mad at him for getting them in trouble, and he doesn’t know what to do. As such, the tome progresses without collective bargaining or discussion of the relative productivity advantage you get from giving reasonable breaks and decent food.The movie addresses these subjects.

These were bold moves for the creative team, both because they are supported so little by the Biblical text and because the United States was still wrestling with the declining but present force of McCarthyism. Edward R. Murrow’s daggers against McCarthy had only struck home two years previous. The major court decisions that would strike down the now-illegal persecution techniques of the anti-Communists were only just kicking into gear. The Senate condemnation measure that greatly reduced McCarthy’s personal influence predate the movie by two years; when The Ten Commandments came out, McCarthy’s health and influence were rapidly fading, but he was still in office.

To add more complexity, in 1949, Cecil B. DeMille had been one of the leaders of the Motion Pictures Industry Council, along with decent actor Ronald Reagan. By 1950, he would also be on the board of the National Committee for a Free Europe, another anti-Communist group that ran Radio Free Europe.

Of course, it is possible to see Moses as both a labor agitator and as anti-Communist (because, as the McCarthy era unfortunately ignored, labor unions are generally not Communist) – but it is interesting to see how cultural resonances have changed, particularly around the improvement of working conditions and the call for the essential freedom and dignity of peoples, as opposed to the unconstrained interest of the employing government or private interest.

7. Queen Nefretiri shows up to bring the Passover story much-needed sexist romantic melodrama.

Nefretiri: I could never love you.

Rameses: Does that matter? You will be my wife. You will come to me whenever I call you,and I will enjoy that very much. Whether you enjoy it or not is your own affair. But I think you will…”

If you enjoy watching self-destructive mutual debasement by wealthy, powerful unforgivably chauvinistic men and opulent, conniving women reveling in the gildedness of their cages – by which I mean if you enjoy the AMC original series Mad Men (ZING!) – you probably love The Ten Commandments.

The Bible does not name the specific Pharaoh who opposed Moses during the Exodus (really old book, remember), but The Ten Commandments (in line with its non-Biblical source material and a fair amount of popular culture) identifies the Pharaoh of Exodus as Rameses II, a.k.a. Rameses the Great, (Ramesses if you’re nasty), and that of course this meant his famous wife, Nefretiri, to which he built a glorious tomb in the Valley of the Queens (Nefertari if you’re nasty)…

Okay, brief aside. I’m not a fan of the changes how we spell names transliterated from other languages and alphabets. I searched for “Nefertiri” in Wikipedia, only to be redirected to an extended list of characters from the Highlander universe, because that was the only spelling for Nefertiri they found. And while this was a joy in itself, it did lead me to think I had perhaps gone insane and typed “List of Highlander characters” into Wikipedia several times in a row, despite being certain I’d typed Nefertiri. It’s not that I haven’t typed “List of Highlander characters” into Wikipedia. I definitely have. It’s just that now they call her “Nefertari” for some reason, even though there was no alphabet in the 13th century BCE.

I mean, I get it – it’s the same reason we have gone from “Moslem” to “Muslim,” which have very different cultural resonances despite sounding so similar the same and coming from a language with a different alphabet. Names collect cultural baggage, and whenever we want to progressively reinvent a new idea of an historical figure or broader identity for political reasons, we have to change the spelling to let everybody know this is a different construction of a person or people. And that’s fine, I guess.

Actually, I just realized The Ten Commandments spells it “Nefretiri,” while The Mummy spells it “Nefertiri,” and now I’m about to throw my laptop against the wall. So never mind.

Okay, so, back to the point, for some reason Ramses the Great and his wife Nefrerejaques are both in this movie, despite not being in the Bible, and Nefredonia of course falls desperately in love with Moses, who is both crazy and married and talking to God about both of these things for most of the movie, so that doesn’t work out. Instead, Nefluenza marries Ramessess, despite the fact that they clearly can’t stand each other, and Rameses is grumpy about her love for Moses as well as his father’s fondness for him. So there is a lot more cattiness and sideways glances and just general backbiting comments in this movie than in Scripture.

Nefretiri in The Ten Commandments

In the end, though, it is pretty great, because Nefretutu introduced into the language an hilarious, breathy, warbling cry of “Mohhhsiss!” that adds a whole new dimension to the Biblical lawgiver/heartthrob, and because if I have any complaints about the Pentateuch, it’s that the original didn’t have Anne Baxter in a sheer harem girl outfit.

Oh, Moses, Moses, why of all men did I fall in love with a prince of fools?”

Yeaaaaah…. awesomeness debatable… moving on.

6. There is rampant metacasting of Hollywood greats.

This is really just two reasons consolidated into one, Vincent Price as Baka the Master Builder Edward G. Robinson as Dathan the orgy guy. Everybody should know Vincent Price as the voice-over on Thriller and the perennially creepy major figure in spooky horror. For those unfamiliar with the name, the voice and mannerisms of famous gangster character actor Edward G. Robinson should be familiar on their own merits, from everything from Chief Wiggum on the Simpsons to common appearances in Looney Tunes cartoons:

In fact, here’s an Edward G. Robinson impression in a Bugs Bunny cartoon:

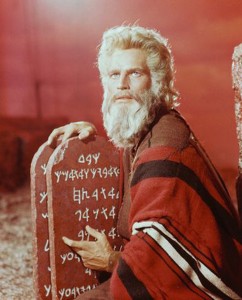

I’ve always enjoyed this kind of metacasting, where an actor is taken way out of the kind of part they’re most commonly seen in and thrust into a totally new genre. Robinson plays a character who isn’t really fleshed out in the Bible — the guy responsible for starting the orgies and making the golden calf, who, because he is Edward G. Robinson, has a lot more to do with the story in the movie than in the book. And he gets this scene, by which point Moses is a man possessed, getting greyer and more bearded the way Goku goes Super Saiyan. I think at this point he’s at Super Moses Level 3.

The exploding golden calf is another thing that was added for the Hollywood version.

The Platonic form of this kind of metacasting is probably from The Greatest Story Ever Told — there is a Roman Centurion played by John Wayne with a jarring line at a bizarre and kind of disturbing moment — made all the more disturbing by the fact that it’s frickin’ John Wayne. I won’t embed it, it’s a little much.

5. Moses is also a broadly tolerant, progressive skeptic.

If this god is God, he would live on every mountain, in every valley. He would not be the god of Ishmael or Israel alone, but of all men. It is said he created all men in his image. He would dwell in every heart, every mind, every soul.”

This is related to Moses’s economic progressiveness, but is even cooler and a bit more shocking, especially in light of the last 15 years or so of culture, which have really polarized and Balkanized public discussion of religion in the United States, such that statements like this, were they to appear in mainsteam movies, would seem far more creepy than they once did — it would be far less likely, if made today, that they would be targeted as overarching statements to a mainstream, rather they would be acts of determined partisans, and the feel of that is different.

It is debatable whether Moses here means that everybody should observe Judeo-Christian, or rather that a God, if real, would extend past Judeo-Christianity to all people and all beliefs, which is an ambitious and aspirational, and, as we’ve found in our relative upswing in political/religious and political/antireligious hostility, difficult.

I prefer to read it as Moses being progressive in his approach to divinity, identifying a very broad definition of God that incorporates at least a hopeful possibility for all people, which is of course very different from the book of Exodus, which is very specifically focused on the problems and solutions of one single group.

The Moses of The Ten Commandments is of two minds about God — one when he is in command of his faculties, and is skeptical about God and people’s claims as to what God is and what God can do, and another when he is caught up in the transformational energy that grows his long grey beard and gives him that frenzied look in his eyes, when he serves as a prophetic mouthpiece for God with such a profound understanding of what he is saying that he doesn’t really stop to explain it. It is interesting in the movie that these two do not reconcile, and Moses the individual is somewhat lost in Moses the historical force — although you get the sense when his arms are up and the sea is parting that somewhere in there he is happy.

But there is definitely a metanoia — Moses goes through a psychological breakdown and reconstruction, and his forceful introduction to God is pretty traumatic and not very humanized, specifically because he comes to it from a pretty skeptical place. It demonstrates an almost Kierkegaardian attitude toward the harrowing difficulty of juxtaposing religious belief with rational thinking, but still retaining the possibility that some might make the leap.

4. Pharaoh converts to a grim, domestic form of Judaism.

Pharaoh does make the leap, but in the entire other direction, being convinced of the reality of God, but being thoroughly nonplussed by it and not wanting to be involved in it at all. It takes a whole lot of the wind out of his sails.

There is no evidence anywhere that after meeting Moses, Rameses spent the rest of his life a cranky believer in YHWH, or that he ever considered murdering his much-beloved wife, even if it was to stave off a very awkward silence.

3. You can cut the sexual tension between Moses and Pharaoh with a knife.

The Ten Commandments explores to a much greater degree than the Bible the relationship that Moses and Pharaoh have as adopted brothers. In the Bible, Pharaoh, his heart hardened by God, is a lonely, alienated figure who seems to not understand what is happening and how much of it is his own fault. He certainly does not open up to or reach out to Moses in any meaningful way. In the movie, there are many moments of vulnerability, status reversal, confession, transformation, exultation and anguish on both sides — and in the end Moses is the more distant, transformed person (although in a way he clearly enjoys), and Pharaoh has been made familiar and more personal in his unhappy marriage.

It is definitely the kind of intimate relationship between two men that has lots of subtext and a certain laughable quality that comes from a quirky chemistry juxtaposed against the at least attempted seriousness of their portrayals and a lot of forced, awkward distance. Hey, you don’t have to take my word for it. The images speak for themselves:

Oh, by the way, in the movie, it isn’t God who hardens Pharaoh’s heart. Not really. Instead they blame the woman for doing it.

Yeaaaah, this movie is lucky it has so much else going for it!

2. “So let it be written. So let it be done.”

This phrase is presented as one of the most authoritative lines in the movie, said by both Pharaoh and God, and is not drawn from the Bible. Nobody really responds to it or thinks it is strange.

This also speaks to the general rhetorical flourish and gravity of the speakers in the film. In the Bible, Moses repeatedly refers to himself as a poor public speaker, asking God for help influencing the people around him. This is why God gives Moses so many visual tricks to pull off (the one most commonly forgotten being his ability to transmogrify his hand in and out of leprosy just to show he can). Moses can’t just go to Pharaoh and tell him the Hebrews have to become Israelites. That would be crazy!

But with Heston and Brynner doing their thing, it’s hard not to imagine at least some minor angels or incarnate virtues of some kind stopping by for pointers on how to speak with purpose.

1. Moses must endure a desperate struggle to survive wind machines, pratfalls, and epic desert voice-overs.

These three and a half minutes or so are definitely in my top 10 of favorite movie sequences of all time. My appreciation of it comes in waves:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oy1K3JBz1DQ&t=95m20s

The traditional account of these events, according to the King James Bible:

Moses fled from the face of Pharaoh, and dwelt in the land of Midian: and he sat down by a well.”

When Moses goes to sit by a well, it is serious business.

So let it be written! So let it continue in the comments!