When The Huffington Post writes that Katy Perry has unfollowed Russell Brand on Twitter — that “the 27-year-old singer clearly doesn’t want to know what Brand is up to, and knows the best way to do that is to completely disconnect from her soon-to-be ex” — who is speaking thus? Is an intrepid reporter, revealing to us the product of an investigation? Is it a crafty editor, pulling eyeballs and hucking ad clicks? Is it a friend and confidant, speaking with intimate knowledge of the singer’s private moments? Is it a contract web writer keeping herself in Pabst with compelling fiction? Is it Ms. Perry’s publicist, outlining a marketing strategy to skew the “Teenage Dream” singer toward older audiences who identify with women leaving the wrong man behind, embarking through heartache and striking out on their own?

Is it Katy Perry herself, drawing on her intensity of emotion to speak truth to her own condition? Is it the social psychology of gender, speaking from a deep rooting in the minds of many? Is it an echo of Paul Simon? Is it universal wisdom? Romantic psychology? Russell Brand?

"I will be part of your interpretive discourse. Always."

Roland Barthes begins his seminal essay “The Death of the Author” with a similar question related to Balzac*. His answer to his own question seems extendable to the literature of celebrity, from the accounts of their thoughts an actions, to their own statements in the public sphere, to the murmuring curiae across all professional, amateur and social media, to the very names and identities that appear in our lunchtime conversations:

We shall never know, for the good reason that writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing.”

– Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author”

That is to say, nobody is really “saying” that Katy Perry unfollowed Russell Brand on Twitter. We are reading it, but once it is down in text (or really, any medium that is subject to interpretation by a reader), it is no longer attributable to an active, talking person capable of will and intent. Because she is not alive in this context, “Katy Perry” is dead, as are any individuals who might claim to speak for her or about her with authority. Their intentionality no longer exists with regards to this story, or in the collected discourse that makes up the myths, tales, gossip and songs around the literature of Katy Perry’s celebrity existence.

(Russell Brand the celebrity is also dead in this same way, but because of social forces and also because he is somewhat less well-liked, more controversial, and more prone to self-destruction, this is somehow less shocking.)

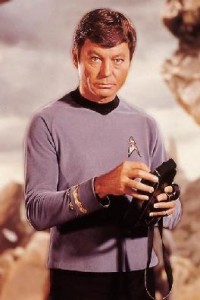

Dammit Jim, I’m a Doctor, Not Perez Hilton.

Bones McCoy needs a Zooey Deschanel-esque portmanteau, a la "adorkable", that combines "spacefaring doctor from the future" with "homespun country wisdom" -- and also "grizzled."

Announcing the deaths of things people like is one of the ways philosophers and theorists socially alienate their involuntary readers — so to step away from Barthes’s postmortem, let’s talk about what it means — in the act of literary interpretation — for identities to shuffle off their mortal coils, for intention lose its claim on meaning, and for the writer to be “dead.” The death of the author is to one degree or another taken for granted in the trendy study of literature these days, and at risk of making the jump from good blogger to bad graduate student, it seems just as clearly so in the interpretation of celebrities.

After all, the interpretation of celebrities and the argument over the meaning of celebrities are a great deal more popular and enthusiastically practiced these days than up-close-and-personal encounters with Balzac*.

But let’s be clear what we’re talking about, because if we don’t, we end up feeling sheepish next to the Wolfenstein 3D enthusiast in the “Neitzsche is dead… God” t-shirt.

We are not saying Katy Perry does not exist as a corporeal being — that she no longer walks, breathes, lives, loves or feels in her brain, a distinct object with its own phenomenology. No, Katy Perry’s physical existence can be experimentally confirmed (though only the very creepiest of logical positivists would make the attempt).

We are not saying Katy Perry deserves no credit for her work, that she is unpraiseworthy, or that she shouldn’t necessarily be paid royalties for “California Gurls,” so long as we live in a society where people possess intellectual property rights — and/or the authority to extend such rights — for which currency is exchanged.

We are not saying that she is irrelevant, or that what she does is meaningless or unimportant.

We are saying that, with regards to the literature that is Katy Perry — and specifically interpreting and attempting to discern the meaning of that literature — Katy Perry herself cannot step forward and claim authority as the author, or as the celebrity. When we are sitting there looking at the Huffington Post article about her unfollowing Russell Brand on Twitter, she cannot point to it and show us where she is in it, or persuasively claim to know what it means, because dammit, she is Katy Perry.

More importantly, since Katy Perry isn’t generally in the business of this anyway, nobody else can step forward and claim to derive that same authority from knowing her intentions.

“I know what this article means, because I am Katy Perry’s number one fan. I know her heart, and I know how she feels about Russell. This is what it really means,” is nonsense.

In saying Katy Perry is dead, we say she isn’t alive and present as a celebrity exerting her intentions through celebrity gossip about her. The many influences on it and the maelstrom of ideas, preconceptions, echoes, references, marketing meetings, Facebook wall posts, and everything else associated with it, once they are literature, aren’t really derived from the willful acts of a celebrity anymore. There are too many intermediaries between the writing and the reading of a text (or, again, any interpretive medium) for the reader to allow for this sort of authorial authority to preside over meaning and interpretation.

The Walking Tall Tale

But what do I mean when I say “the literature that is Katy Perry?” Katy Perry is a person, right? And all this talk we go about doing with regards to her being a person doesn’t make her any less a person, does it? Let’s look back to Barthes:

As soon as a fact is narrated no longer with a view to acting directly on reality but intransitively, that is to say, finally outside of any function other than that of the very practice of the symbol itself, this disconnection occurs, the voice loses its origin, the author enters into his own death, writing begins.”

Definitions of literature in literary theory, whether relative or absolute, tend to flock around this general area — literature is information that doesn’t have to correspond to reality, but can have an effect, whether that is beauty, truth, tension, sublimity or any of the other familiar or exotic goals of literary pursuits, without needing to do anything else.

Poetry is a form of literature. Drama is a form of literature. Film is a form of literature. I’m positing, and I can’t reasonably be the first person posit it, but that doesn’t matter, (especially in discussions of the death of the author — because, after all, as you read this, I am not present in or in relation to it as a living being either) that celebrities themselves have these days so far transcended a relationship with reality that they have become a form of literature themselves, supported by the discourse around them across media and platforms.

Why do these people have a show? They’re just famous for being famous.”

– Every curmudgeon who thinks he is clever but is really just having a bad day, including me sometimes, about the Kardashians

By “the literature that is Katy Perry” I mean that Katy Perry as we read and interpret her — the body of information that we encounter that has this name associated with it in which we look for a certain meaning and/or significance — is far less a corresponding description of a person than a literature in itself, endeavoring in these same familiar and exotic literary pursuits.

Dasein In the Membrane (A.K.A. I Don’t Know If This Rhymes, Because Nobody Uses This Word In Actual Conversation)

As I’ve noted in previous articles and podcasts, I find the term Dasein, drawn from Martin Heidegger’s Being And Time, useful in discussions like this, because it doesn’t bog us down in scientific argument over the qualities of a person or of cognition, or of the functionality of the mind, and concerns us primarily with the thing capable of experiencing “stuff.” Dasein refers to an entity which, “in its very Being, comports itself understandingly towards that Being.”

Sein und Zug

People who are alive in the world are Daseins. Philosophical zombies, theoretical beings who are materially indistinguishable from people but who do not possess subjective consciousness (which I find to be a problematic term because it sidetracks us into discussions of emergent properties and information theory), are not Daseins. Trains are not Daseins. Thomas the Tank Engine, were he to be real, would be a Dasein.

Daseins can be authentic or inauthentic. It is generally believed to be a good thing to be authentic as you’re going about the business of being-in-the-world. Celebrities, especially heavily managed and choreographed ones, with teams of publicists, stunt marriages, scripted interviews, meaningless but lucrative endorsements of useless products, and other such Kardashian endeavors, are often seen as inauthentic. They are fake, phoney, and emotionally detached, their pictures are heavily Photoshopped, their bodies are virtually cybernetic — the litany is familiar; they are not being honest.

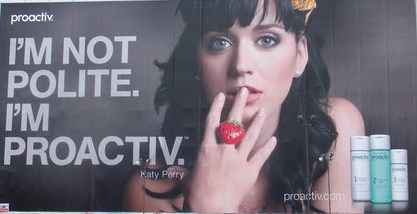

I would take it one step further and say that when you see something like this:

"You gotta have blue hair." - Strong Bad

You’re not looking at an image of an inauthentic Dasein — Hell, you’re not even looking at a person anymore. There is so much interference and cultural interplay in this information that you return to an act of reading as described by Barthes, divorced from the act of writing. You are looking at something “narrated no longer with a view to acting directly on reality but intransitively, that is to say, finally outside of any function other than that of the very practice of the symbol itself” — you are looking at literature with a dead or absent intentionality.

Why Arguments About Objectification So Rarely Actually Go Anywhere Productive

Now, this of course, brings up a major problem. The idea of the death of the author runs afoul of complaints about objectification.

And as much as it may sidetrack me, I have to mention it here, because after posting that picture people are going to yell at me about it anyway in the comments (except I’m not here! And my intentionality does not exist in this work as you read it, ‘natch!).

The idea behind objectification is that by understanding a representation of a person as less than a fully realized person, we instrumentalize or use that person, which, in a Kantian sense, is a crime against the dignity they ought to be afforded as rational beings, and in a Marxist sense, sets up a dialectic that subjugates and alienates them, most likely for the economic benefit of your own class of people.

However, if you want to look at an image of Katy Perry (or even a darker, sparser corner of the Internet where people actually look at Balzac*) and employ judgement in relation to the “thing-in-itself” through any number of rational formulations, or if you are seeking to lift up Katy Perry from her subaltern place in socioeconomic discourse, you will be sorely disappointed, because you are knocking on the door of an empty house. And, no I’m not saying she’s dumb (I’m sure she’s very smart).

Katy Perry isn’t actually there. That image is a literature of Katy Perry, and if you’re looking at it, the intentioned Katy Perry with whom you are seeking to interact with is already dead.

So, arguments about objectification often run into this problem, as for political reasons people continue to will that literature be capable of producing its causal agent for redressing, redefinition or redemption, when that agent is long absent and even asking for it is an incoherent act.

This of course does not mean objectification is good, or that protesting it is bad — but just that most of the time it is quite difficult to do anything about it, except to try not to allow systematic trends in its use to create deleterious effect on people’s standards of living.

The important thing to remember here is that these problems are intrinsic to the act of interpretation and finding meaning. One of the ways to try to get out of this is to not try to find the meaning in things, but to engage in art in different ways. That in the rest will have to be covered in another article.

Katy Perry Is A Commercial Enterprise

You may notice this advertisement exemplifies pretty much everything I've been saying. You might.

You might have stopped earlier in this article when I said something that was clearly and knowingly incorrect, or at least incomplete:

Katy Perry herself cannot step forward and claim authority as the author, or as the celebrity. When we are sitting there looking at the Huffington Post article about her unfollowing Russell Brand on Twitter, she cannot point to it and show us where she is in it, or persuasively claim to know what it means, because dammit, she is Katy Perry.”

-Me, “Earlier In This Article (We were all so young then. Look at the hair I had! Crazy!)”

If you’re paying attention, you might have stopped here and said of course she can! Dammit, she is Katy Perry!

And indeed you would be right — Katy Perry could indeed step forward and make an authoritative statement about what the article saying she unfollowed Russell Brand on Twitter actually means, and she’d have the power to back it up. She could have her lawyers send a cease and desist. If you did the wrong thing with her celebrity, of which she did not approve, she could sic Chris Dodd on you. I don’t get the sense that Katy Perry is mean-spirited enough to do these things, but people who would lay some claim to her celebrity intentionality would.

Regardless, let’s say she did do it, would she be doing it because she is correct?

Far from a refutation of the death of the author, this power is one of the big reasons why the essay “The Death of the Author” exists — because this sort of act is not an act of interpretation, but an act of intellectual tyrrany — that if you aspire at all to freedom or dignity in the human mind, you should find it abhorrent that in capitalist societies and other similar societies people of wealth, power and influence get to step forward and claim to everybody else what something means just by virtue of them being the “author,” which is of course cognate with the word “authority.”

If celebrities are the modern-day folk heroes — the lenses through which people see their own lives, craft their relationships, and plan their own rituals, it the literature of their day-to-day is in celebrity gossip — what right that derives from truth rather than power does Katy Perry or one of Katy Perry’s lawyers have to come along to a random dude or lady reading People magazine at the checkout line and insist on what it means?

It is thus logical that in literature it should be this positivism, the epitome and culmination of capitalist ideology, which has attached the greatest importance to the ‘person’ of the author… The image of literature to be found in ordinary culture is tyrannically centred on the author…”

– Roland Barthes, Ibid.

If celebrity is literature, and I think it is, and the act of interpreting celebrity is confined to the reader of celebrity, which I think it is, and if all the confounding factors make intentionality in the creation of celebrity untransferable, which I think they do, then for an interested party (including the Dasein associated with celebrity of the same name) assert authority over readings of the literature of that celebrity by virtue of authorship or celebrity itself is an act of economic and social power — not interpretive value, reading, or meaning.

It’s bullying. It’s not nice. And I’m gonna tell Roland Barthes**, so nyah.

Let’s finish with something from the end of Roland’s essay, for symmetry:

Thus is revealed the total existence of writing: a text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author. The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination… Classic criticism has never paid any attention to the reader; for it, the writer is the only person in literature. We are now beginning to let ourselves be fooled no longer by the arrogant antiphrastical recriminations of good society in favour of the very thing it sets aside, ignores, smothers, or destroys; we know that to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.”

– Roland Barthes, Ibid.

**- Roland Barthes is dead. Unfortunately. PBUH

*- Always pun intended. Always.

I would like to interrupt my own reading of this piece to respond with shock and disappointment to the notion that Russell Brand is less well-liked than Katy Perry. I’ll get to the rest shortly… but really, Katy Perry is grating, unlikable, and only marginally talented, while Russell Brand at least has “Bedtime Stories” to redeem him.

OK. So, I think the most obvious concern here is the goal, or lack thereof, towards which you are driving this point. Barthes is demanding the birth of the reader. He is not just insisting that the field of literary criticism wake up and attend the reader, he is calling for the reader to own and acknowledge his own agency. I can’t help but find that point moot in this context. Modern “readers” of celebrity are by no means ignorant of our own power. Far from the world of literature (where we still, decades after Barthes, “attach[] the greatest importance to the ‘person’ of the author…” – to varying degrees in critical circles but almost exclusively in the general public), celebrity is an arena where its “readers” consistently assert authority of interpretation and description.

Which brings me to the point that, far from being tyrannical demagogues bent on denying the “reader” their due, celebrities “these days” are only just barely getting their feet in the door in the realm of authoring their own identities. When challenging the authorship of celebrity, you are only seldom if ever challenging the people behind the personality – celebrity is most typically authored by managers, record labels, publicists. Elvis was not the author of his own identity – that would be the Colonel. For the Beatles, Epstein. This is even more true in recent years, with (for example) the Disney machine, which starts crafting identities for its shills when they’re barely even old enough to cognitively process *how* to define themselves (something normal human beings begin to grasp fully as teenagers).

It’s only with the advent of social media, and lessons in self-marketing, and the ability of artists to achieve celebrity without intermediary, that we’ve begun to see any sort of self-authorship taking place. The Dasein behind the celebrity is not its author, but just another layer in the “tissue of quotations” that is the text. In many ways, it is they who need to rise up and become better “readers” (and therefor complicit authors) of themselves. The public, far from not realizing its role, increasingly relishes it, and celebrities are routinely punished, to varying degrees, for their attempts to undermine OUR authorship (think Britney Spears).

There are exceptions, of course – Madonna managed to embody the tyranny of the author, but only by killing herself every few years and resurrecting herself as someone new (she is at best a collection of short stories, rather than one unified text). That, however, was before the real rise of the “reader” of celebrity, which perhaps reached its apex in Princess Di’s demise – precipitated as it was by her quest to escape the paparazzi (the ultimate agents of the “reader”) and followed as it was by en masse readings and rereadings of her as a text. That was a defining moment in the realization that celebrities were no longer who their authors (their publicists) said they were (and certainly not who they claimed to be) but instead were defined solely by their readers.

I’d say Lady Gaga has made a decent go of fighting against that tide, but she’s in a different world than Madonna was. Only big mega-corporations like Disney come close to maintaining authorship against the tide of the reader, and even they fall short (think Miley Cyrus – she didn’t wrest authority over her identity from Disney, the internet did).

I guess this is all a long-winded way of saying that Katy Perry never lived. Her authorship was delegated long ago. She, the Dasein, the Katy Perry behind Katy Perry, has never had any claim of ownership or authority over her identity, and the best she can hope for is to become a partner in her own reading.

And that’s why I killed Ferdinand de Saussure.

“So, I think the most obvious concern here is the goal, or lack thereof, towards which you are driving this point.”

It is kind of funny that the first thing mentioned about an article about the death of authorial intention is what the intention of the author is.

Hey, I’m the author; I’m dead. You’re the reader – you’re the one who matters here. Maybe my article doesn’t actually make a point. It certainly falls way short of serious literary criticism.

But if we put that aside for a moment and I can do some reading of this piece and further authorship/discourse since my name happens to be on it, I’d say that it’s very rare that I write a piece for Overthinking It is that just trying to make a point (I think the time I was mad at the Starcraft II plot was the main time I did that).

I like my writing to be entertaining, thought-provoking, absurd, witty, even pretty. I tend to make arguments self-consciously, acknowledging my own absurdity and inadequacy as I make them. The last thing I care about is whether serious critics think my writing is making a point that happens to be important.

I mean, it’s nice to be validated, and I suppose it’s cool to feel like my insights might mean something to people, but that isn’t what’s driving me to do stuff like this. If I wanted to be important to the vanguard of cultural criticism, I wouldn’t throw silly pictures of DeForest Kelley into my articles.

That said, there are clearly big chunks of the article that are expository, so I’ll address what you’re talking about.

1. Last night, while social forces were conspiring to write this article without my intervention, but with the use of my hands and computer, my main feeling was around explaining and riffing on the concepts in Barthes’s essay to people who may not have encountered them before.

One thing I do tend to disagree with a lot of literary critics on is the localization, both geographically and temporally, of literary phenomena. I don’t think things necessarily change all that completely from one time or place or time to another – at least not in an organized, clean or systematic way. Even when new materials or media become available, a lot of the old stuff still applies, and a lot of the time if you’re seeing something for the first time, it might just be because you didn’t see it before — not because it wasn’t there.

Individual times and places still have a huge variety of subjective experience associated with them — that if there’s an idea you can conceive, somebody somewhere is probably thinking it. A lot of the time when somebody thinks there is a sea change or something entirely new going on, really it has happened before or is happening concurrently in other ways or isn’t happening as discretely as they think it is.

In other words, “Peoples is peoples. No is buildings. Is dancing! Is music! Is tomatoes! So you see, peoples is peoples.”

I am very skeptical of revolutions, material dialectics, and people who claim that they’ve got it all figured out and know the way forward. As Milton would put it, “New Presbyter is but old Priest writ large.”

Also, I don’t think of cultural progress as something that introduces new ideas that supercede and replace old ideas. The old ideas are still there, and the new ideas probably aren’t all that new or special, except in the beauty, spirit, elegance or robustness of their articulation.

So, what I mean by this is, I don’t think the death of the author happened this one time when Barthes was talking about it — and he acknowledges this to an extent within his essay. I think it’s an idea about literature that is always in play. I don’t think discussing it is irrelevant to the present day because the academy tends to act toward literature in a different way than it used to, or because the business of entertainment has changed.

On to the more specific stuff.

– It’s interesting that you see the paparazzi as the “agents of the reader.” I see them very much as the agents of the author. It probably didn’t get into my essay, so rather than say what I “meant” (which I guess is hogwash so close to this article), I’ll add new stuff.

The commercial machinery of celebrity, even with the constant participation of readers through social media, their own conversations and other types of engagement, still tries through political and economic means to use intentionality and appeals to authority to control the reading of celebrities-as-text.

But when I’m saying the celebrity is dead in much the same way the author is dead, maybe it isn’t that the celebrity is the author. That’s clearly not how it functions.

But consider product endorsement. When Katy Perry is on a poster saying “I am proactiv” – there is an appeal to the authority of the celebrity there, that Katy Perry is “saying something.”

Now, we know Katy Perry the Dasein isn’t saying this thing. But the peopke around Katy Perry _are_ attempting to say it, and is relying on the intentionality of that created celebrity as if it were a Dasein to express their own intentionality through to the reader of the ad and control how it is interpreted.

I guess the biggest difference between my and your interpretation of this is I see those people as primarily aligned around authorship – that they are authoring Katy Perry the celebrity and trying to position her as an authority rather than as a literature by virtue of their social and commercial power – and you see them more as aligned around readership – that they are interpreting Katy Perry themselves and creating a dialogue with the people looking at the ad.

I think I see it your way too. Makes sense. They could be doing both. And they might have been doing both for a long time.

I mean, you talk about Princess Di, I could just as easily talk about Rock Hudson, and how a great many people (though perhaps not as many as with Diana) knew that Rock Hudson the celebrity was a literature and not a person, that he wasn’t the author of his own life, and that the life he experienced and the life that was publicly portrayed for him were fundamentally different.

I could go back and say that we can see Augustus understood this by looking at his Res Gestae — that the public life Augustus said he had was a very deliberate construction that didn’t correspond to a realistic idea of a human being, and that to a degree a lot of people were complicit in this and aware of it.

Did people really believe when Augustus refused a dictatorial appointment or a consulship between he wanted to remain “First Citizen” as a Tribune, that he was doing it out of a civic commitment to limiting his own power born out of personal virtue? Did people look at the idealized statues of him and belief that’s who he must be, because that is who he says he is? Did the people who knew him actually think he was a God?

I’d wager that at least some people knew what was going on – that Augustus was effectively the Emperor/King, and that the only reason people talked about him the way he wanted to be talked about was because of political, military and economic inducement. That to some people, the celebrity-as-author was dead thousands of years ago.

So, maybe transfering the source of the appeal to authority of the personage of Elvis from Elvis to the Colonel doesn’t make Barthes irrelevant – it just begs the question of intentionality, kicking it down the line from the celebrity as a Dasein to everybody invested in the creation of the celebrity.

Or maybe not. Just riffing at this point. Thanks very much for the awesome comment – would take me a really long time to totally unpack it.

Hope at the very least the article was entertaining and/or interesting :-)

Haha! You’re right; that IS pretty funny. I think the fact that I did that is perhaps a bit of (subconscious) evidence for my assertion that Barthes’ truisms have yet to be fully realized in the general world view, but more on that later, perhaps, if I remember. Regardless, imagining away my misplaced attribution, the text itself seems to be gesturing towards a conclusion that I feel is illogical.

By mapping celebrity culture onto the concepts of “author” and “reader,” there is a tacit implication that they follow the same developmental arc, especially when the piece ends with Barthes closing rallying cry: “we know that to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.” I still maintain that the reader of celebrity needs no such rally, that the hypothetical reader who would have paused early in the article and exclaimed “of course she can! Dammit, she is Katy Perry!” exists, if at all, only as a minority.

You’re right, of course, that your article is a piece of entertainment. It certainly served as such – if I hadn’t been entertained, I wouldn’t have responded! (I even forwarded it to a former professor of mine who teaches on Barthes in a course that studies varying aspects of modern culture, because I think it would be an awesome read for kids just being introduced to that essay) However, when you say “The last thing I care about is whether serious critics think my writing is making a point that happens to be important” – well, yeah, I get it… but at the same time, I would hardly bother to come to this site if I didn’t like to overthink things, which is, after all, what I did to your piece (although not particularly well, I admit).

Anyway, to get back into it… It’s becoming clearer from your response that much of our disagreement lies in our differing readings of Barthes. I’d tried to ignore that, and focus mainly on his application to the current situation, but it seems like it’s more central than I’d thought, and though I didn’t want to challenge your post at that deep a level, I guess I’ll lay out what I think the discrepancy is, and see what you think (if you even still care!).

Basically, as I read your argument, you believe that Barthes is talking about something that already exists, and which he is simply revealing. Thus, you feel comfortable drawing a comparison with something like celebrity culture, where this truth is also already self-evident. Now, I’ve only read the essay a couple of times, and I didn’t refresh myself before engaging with this, which might be my mistake… but I’ve always interpreted “The Death of the Author” as a plea, to the literate public, to reclaim the ownership of meaning-creation that had been lost to them for the prior century.

I don’t think, as some scholars would argue, that “the cult of the author” arose for the first time during the 19th century… but “authorship” certainly had a vastly different meaning up until that point… and the times in history to which I *would* point as seeming to privilege authorship did so in a very different way (the Greeks, as I understand it, held *play* competitions, not *playwriting* competitions, meaning that although the names of authors are what have come down to us, the decisions were based on the collaborative efforts of performances, not necessarily the authors’ written work out of context). The rise of the author as a figure of, well, authority does have a ton of other parallels to celebrity culture, as such, which make this even more interesting (and on which I probably should’ve focused my original response… ah well…)

So, basically, I’m agreeing when you say that Barthes is saying something that’s always been known (and I would never claim that Barthes is irrelevant!) – I just feel like he’s speaking, contextually, from a place where that knowledge had been extremely damped down for many years, and he’s calling on people to *return* to that previous conception of authorship (something which I still feel we have yet to do, en masse as a culture).

OK, on your other point – it feels like you’re conflating two different advertising techniques when you talk about celebrity endorsement as if it *is* an appeal to authority. I don’t think it is. (the appeal to authority, obviously, – in this case – would be someone purporting to be a Real! Doctor! telling you how well Proactiv works… on their website, for example, underneath the pic of Katy Perry is a photo of some woman in a lab coat with the text “Our experts want to help you achieve the best skin possible!”) The celebrity endorsement, on the other hand, has nothing to do with the Dasein Katy Perry, or even her authors, but with the objectified “philosophical zombie” (I love that!) that is her celebrity literature. She is used because people want to look like her, approximate her – not because they think she has value in assessing the product (an ability only her Dasein would possess, if at all). I don’t think it’s expressing any intentionality at all.

Think of how many adolescent girls ran out and bought “Wuthering Heights” because it was Bella’s favorite book in “Twilight.” Would they have done that if it were Katy Perry’s favorite book? Probably not, because she does not have any interiority as such. She is not viewed *or even imagined* as a complex Dasein, and more importantly, we, as readers, know this. People relate more genuinely to a fictional character, because they’re exposed to her fictional interiority, then they do to a celebrity shell.

I wonder if you’re right, that people were as aware of Rock Hudson and Augustus as literature as they are now, post-Diana. I still think that was a turning point in our modern era, but I don’t know when celebrity authorship firmly established itself as something to turn *against.* I wouldn’t be too hesitant to assign the phenomenon to Disney, around the Annette Funicello era, but that could just be my penchant for blaming everything on Disney.

I’m going to be pondering that for a while, now…

So one of the interesting things about authorship, when we go down this road, is the distinction between texts that are and are not authored. We tend to intuit the existence of an author behind “artistic” products like books, songs, films, paintings, and so on, but not behind practical texts like those pamphlets that tell you the features of your new microwave, and not behind folk texts like fairy tales. We know that someone wrote them, of course, but we kind of have to remind ourselves of that fact.

Are twitter feeds governed by an author-function?

Tweets are definitely authored, even the anonymous ones. This is why it’s a scandal when a middle-eastern lesbian on Twitter turns out to be a 40 year old white guy from middle-America. When you or I in our personal lives do something like follow or unfollow a twitter account, or “like” something on facebook, that’s definitely authored behavior. The persona that we create through our online activity is given meaning by the person behind it. We all know that it’s a pose, to at least a certain extent. There are things that we like that we would never dare “like,” and things that we “like” to be ironic or provocative or polite. But there is nevertheless a sense that there is a person (a Dasein, I guess) behind that gesture, who is trying to be ironic or provocative. This persona functions as a seal on the discourse. Without telling us what the real meaning is, the persona establishes certain limits for it, in that you can’t make claims about the meaning of the gesture beyond a certain point without also making a claim about the gesture’s author.

Not all twitter accounts have authorship, though. Nothing that @GeneralMills tweets will tell us anything about the subjectivity of General Mills, because there is no such subjectivity. The existence of the account tells us that the company cares about branding, and that they think they can capitalize on this newfangled social media razzamatazz. But nothing it says can be “revealing” in the way that an authored statement can. If @GeneralMills started posting pictures of male genetalia, there would be a scandal, and someone would get fired — but we would never ask “do you think he really did it?” the way we did about Anthony Weiner, because there’s no “he” to have done it.

Celebrity twitter feeds fall somewhere in the middle, depending on the celebrity. Their personas are so groomed in general that I typically assume their online personas are run by a team of publicists. On the other hand, a lot of celebrities seem to value twitter precisely because it’s a place where they can be autonomous and unguarded. And I think the confusion, that sense that there just *might* be a real person behind the persona, is what accounts for (or maybe allows?) the fascination of celebrity.

“We are not saying Katy Perry does not exist as a corporeal being”

Hey, I’m saying that!

http://weird-proof.org/2011/02/24/russell-brand-does-not-exist/

Hi blogger, i must say you have high quality posts here.

Your blog should go viral. You need initial traffic boost only.

How to get it? Search for: Mertiso’s tips go viral