“Party Rock Anthem” by LMFAO is in serious need of the Musical Talmud treatment.

(Note: although the zombie theme of this music video is begging for deconstruction, I don’t see it tying into the lyrics, so we’re “bracketing it” from this analysis. But feel free to pick it apart in the comments.)

It’s not a rock song–it’s dance pop through and through–and yet, the title is “Party Rock Anthem,” and there’s a prominent reference to the most rock of rock bands, Led Zeppelin.

Is this meant to be a thorough repudiation of “rock” music as it’s commonly known, or is it cleverly appropriating some of that spirit into a new context?

What does it all mean?

From the iTunes "Pop" section

Party rock is in the house tonight

Everybody just have a good time

And we gonna make you lose your mind

Everybody just have a good time

The song asserts in the opening chorus that “party rock is in the house tonight,” which immediately forces us to confront the tricky definition of “rock” as a music genre. I stated earlier with confidence that this song is clearly not “rock” and that it’s “dance pop,” and most of you would probably agree, but we need to ground ourselves in some common understanding of these labels.

Musically speaking, the simplest way to set “rock” against “pop” is instrumentation. “Rock” music is typically driven by the guitar and backed with acoustic drums and electric bass, while “pop” is more likely to rely on electronically generated sounds for its instrumentation. And although “rock” music has incorporated more electronic sounds over the years, the guitars are still very much front and center in the sound. Let’s use the iTunes top “rock” songs list as shortcut to illustrate this. Scan through the artists and listen to the previews. This is the sound of modern rock. Now do the same for the iTunes top “pop” songs list. Way more synth, way less guitars. So it’s no surprise that iTunes classifies LMFAO in the “pop” genre.

From the iTunes "Rock" section

OK. That was a long-winded way of establishing that musically, no one is going to accept this as “rock.” But what about the non-musical aspects of “rock”? Consider the following phrases:

“This rocks.”

“Let’s rock.”

“Rock out!”

“I’m rockin’ the new Amazon Kindle.”

“This party is rocking.”

These expressions of enthusiasm, energy, and power obviously have roots in the energetic aspects of rock music, but can be used to describe things that are, strictly speaking, non-musical. Hence LMFAO’s ability to channel “rock” in a non-rock song.

But here’s the problem. All of the examples above use “rock” in the verb form. A subject does the “rocking,” or is characterized by “rocking.” But in the song “Party Rock Anthem,” the word “rock” is used exclusively as a noun, as a thing that’s “in the house.” We’ve already established that this song isn’t “rock music,” so if that’s not “in the house,” then what is?

LMFAO has effectively created a new definition for the noun “rock.” “Rock” is a state of mind, not a music genre. LMFAO is simply taking the evolution of the culture that grew up around “rock” music to its next logical step: divorcing it from its source music altogether.

Huh. I guess rock music really is dead.

But it’s not that LMFAO wants rock music to die, nor are they necessarily mocking it by calling a dance pop song a “Party Rock Anthem.” No, they’re just tapping into the benefits of rock culture without using any rock music because the larger music cultural context allows them to get away with this. “Rock” musicians are no longer the cultural titans that defined American popular music with their monster guitar solos and crunchy power chords. In a fractured “rock” landscape that includes everything from the Insane Clown Posse to Foster the People, no “rock” hegemony exists to challenge a “Party Rock Anthem” that is not a rock song.

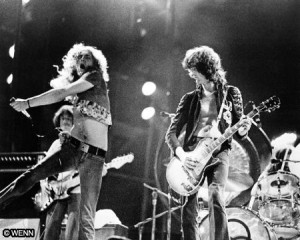

Led Zeppelin, playing rock with rock music.

But that rock hegemony used to exist. It was led by bands like Led Zeppelin, which LMFAO seems to be writing off in these lyrics:

We party rock yea!

That’s the crew that I’m repping

On the rise to the top

No led in our zeppelin

It’s clear that LMFAO considers themselves to be ambassadors of this new rock-less rock and are not ashamed of it (“that’s the crew that I’m repping”). It’s also clear that they see themselves, and presumably, their rock-less rock, ascending in popularity and achievement.

But their vehicle for ascendance is still a “zeppelin,” albeit a “led”-less one. We see in this a reflection of how LMFAO has appropriated of the cultural spirit of rock (zeppelin) without its musical and occasionally pretentious, moody thematic features (led). They clearly feel that they aren’t weighed down by this burden and are thus able to make rock-less rock music entirely on their own terms.

Conclusion

I guess I do see a little Monet in this...

LMFAO, a dance pop music duo, is boldly advancing its “party rock” music, one that is devoid of any musical aspects of rock but seems to be channeling the broader culture of rock. It’s easy to write this off as a careless misappropriation of one art form into an highly dissimilar form. Like evoking nineteenth century impressionist oil paintings when talking about a crayon drawing just because they’re both renderings of a tree.

I don’t entirely disagree with this statement. But do give LMFAO credit for boldly defying the commonly accepted use of the word “rock” in music. And lest we forget, rock music was born out of defiance of social and musical norms. So perhaps it’s only natural that once “rock” itself has become a norm, “rock” will come along to challenge it.

party rock is a nickname for lmfao’s group because of their 80’s influence. a lot of 80s rock used a synth, too, and you should note its fusion with breakdancing that makes up their style, also very big in the 80s. you should learn a little about a band before writing an article on them

There are other precedents to this… right off the top of my head, there’s Robbie Williams’ “Rock DJ,” which was certainly not a rock song in any way Elvis, the 70’s/80’s glam rock outfits, or the punk scene would recognize. I’m sure you could probably find other songs with “Rock” (non-verb/non-gyrational) in the title, performed by techno and dance outfits (I’d check AllMusic.com if I was really interested in the research). I suppose, at its most abstract, “rock” isn’t a genre, so much as an attitude, a tribal enthusiasm for music that flourishes in the hands of youth.

“Every day I’m shuffling” is also a reference to the Rick Ross song “Hustlin’,” which is very much not a rock song, and seems to be making fun of the seriousness and self-importance of rap and hip hop. That could be another reason it is called “Party Rock” – to try to distance it from other sorts of current dance/club music that are not rock or rock-influenced. It’d be like wearing Indian war paint because you’re tired of Western comformity – showing that you know nothing about the thing you are imitating except that it is exotic and cool.

Some other conceivable ambiguities that could be adding shades of meaning: the “party rock” could be a drug. It could also be a person or a crew that is “in the house” that referred to metaphorically as a big, heavy thing or a stable base – “the party rock upon which I will build my church.” This would add credence to “Party Rock” as a potential Jock Jam to be played at stadiums (and to me the tune does feel a little Jock Jammish) – the player or team is the Party Rock, or they are collectively with their fans.

And “rock and roll” was originally a euphemism for sexual intercourse, so that could be part of it.

I was actually gonna comment that my impression of Party Rock, as used in the chorus, was of ecstasy and other rave drugs, as confirmed by the use of phrases “good time” and “lose your mind,” but Fenzel beat me to the punch. And I also thought that definition’s pretty obvious. (Related query: Has Red Bull become the drug of choice at the U.S. club scene, or is it more of a fractured world where stimulants of the solid, liquid, and gaseous kind have their own niches?)

Which is why I’m also latching on to Lee’s take, which deals with the disambiguation of the term “rock music.” I’m confused with what is defined as rock nowadays (and the most popular offshoots, pop rock and alternative rock). I guess I’m a fan of the three/four-piece/Rock Band/Guitar Hero definition of rock (vocals, bass, guitar, drums), and I’d rather see a multitude of ” rock” definitions in the genre section of Wikipedia, rather than just seeing “Rock” and confusing the hell out of me.

One point that I think supports your thesis, Mark, but which I was surprised to see you leave out, is that the song is not “Party Rock Anthem.” It’s “Party Rock Anthem.” That is, LMAFO use “party rock” as a compound noun (note that “Party Rock Anthem” is itself on an album called Sorry For Party Rockin’), as well as like a brand name (their two previous records were both also called Party Rock). So not only is this piece right on, but they are pretty clearly aware that the phase “party rock” describes a thing that is different from “rock”: the spirit, energy, and state of mind of rocking parties.

Cool, advertising a song within a song (a meta-song?). Harkens back to Ignition (remix).

So the zombie theme, is it like that saying “bad sex is better than no sex” so in the video it’s “bad dancing is better than no dancing?”

It’s sort of anti-“Thriller” in that the shuffle dances moves of “Party Rock Anthem” are so easy it’s hard to be intimated not to try it for fear of getting it wrong, but in that simplicity are actually closer to zombies than “Thriller’s.” The joy of dancing “Thriller” is the mastery of something complex, while in “Party Rock Anthem” it’s the joy of not being burdened by any complexity.

The only way I could understand the zombie motif tying into the lyrics is if you accept the unlikely premise that this is all being done ironically much in the same style that Beastie Boys once did Fight for Your Right (to Party). That is, the parody of modern party culture has become so complete that the disguise has become not only been accepted but absorbed by that same subculture. The party zombies cannibalize open mockery of their zeitgeist. Really if you accept that to be true, then the played straight acting of the musicians and high production value are both consistent with an artistic retelling of Beastie Boys’ tragic comedic history.

The image of the film presents the main body of the song as a defense mechanism parallel to themes in every post apocalyptic eulogy of How long can you sacrifice your humanity before you lose it. What is the difference between survival and defeat? When are LFMAO party zombies and when are they not?

That was the best I could do.

” That is, the parody of modern party culture has become so complete that the disguise has become not only been accepted but absorbed by that same subculture.” Indeed, this is a major component of the post-postmodern hipster milieu, as also seen in Ke$ha’s parody desperation, and in the entire sub-sub-genre of “brostep” (eg, Skrillex).

The zeit, as it were, has no geist.

What? Run DMC have been the Kings of Rock for over 25 years.

“But do give LMFAO credit for boldly defying the commonly accepted use of the word “rock” in music.”

The term rock has a long history in rap music. I think LMFAO are referencing that tradition, rather than making a critique about – or carelessly misappropriating – the spirit of rock and roll.

Indeed, one could even say that rock and roll could never hip-hop like this.

As someone said above, “Party Rock” is the name of LMFAO’s hip-hop crew. So writing about the reinterpretation of ‘rock’ in this song seems beside the point, since the idea is that Party Rock, the crew, is awesome/fun and this is their ‘anthem’. It’s like trying to determine the definition of the word “mode” or “flip” in Flip-Mode Squad, and it smacks of not actually bothering to look anything up about the band before you wrote the article.

First off, I just looked at the LMFAO Wikipedia page, and it doesn’t say anything about a crew named “Party Rock.” That doesn’t mean it’s not true, but maybe it’s not as well-know as you claim.

And even if it is true, I think the term “Party Rock” is a lot more complicated than that. The group’s second album is entitled “Sorry for Party Rocking.” Does that sound like it refers to a group of people? It sounds like a verb to me.

I’m not a huge fan of LMFAO or anything, but their inaugural hit song, “Shots”, has the line: “I’m with the Party Rock crew, all drinks are free.” and Party Rock Anthem goes, “Party Rock is in the house tonight.” Just by having heard those alone, I am aware that LMFAO belongs to the Party Rock crew.

Now, given that their crew is known as Party Rock, and that this is literally one of the first things the band made known about themselves (the 2nd line in their 1st hit single), I would personally assume that the primary references they make when they discuss “Party Rock” and “Party Rocking” are their crew, and the activities their crew gets into (getting drunk and partying/dancing).

First, to address the research question: I did do some research on LMFAO prior to writing this. It was fairly cursory, but it was present. Could I have done more? Sure, and I’ll aspire to do more next time.

That being said, even if I had known that about LMFAO (that “party rock” was the name for their crew), I don’t think that would have changed much of the article’s content. Given the “Led Zeppelin” reference and multiple references to “rock and roll” in the lyrics, it’s clear that LMFAO wants people to think about the traditional definition of “rock” and how they’re subverting/reinterpreting it. Even if they’re mostly referring to themselves when they say that “party rock is in the house tonight.”

Huh…I always assumed the lyrics were “Party rockers in the house tonight”, not “Party rock is in the house tonight”. Are we absolutely sure that it’s “rock is” and not “rockers”? If it’s “rockers”, then that would help disassociate themselves from the “rock” genre. Like you said, it’s possible to use “rock” without referring to the musical genre (“Rocking a new Kindle”, “Rock out”, “Let’s rock”, etc). They’re “Party Rockers”, ie “Rocking the Party”.

But again, that’s only if they’re saying “rockers”, not “rock is”. Great article, nonetheless. :)