The “Baby” Project (a series of covers of the Justin Bieber song “Baby” across genres) is on hiatus, but Bieber Fever still burns strong here at Overthinking It, in spite of the conspicuous absence of new material from him over the past few months. What’s going on?

The “Baby” Project (a series of covers of the Justin Bieber song “Baby” across genres) is on hiatus, but Bieber Fever still burns strong here at Overthinking It, in spite of the conspicuous absence of new material from him over the past few months. What’s going on?

Puberty. The kid’s voice finally changed at the late age of 16, and he spent much of 2011 working with a vocal coach to manage the transition. It appears he’s made it to the other side, as his first new single in months now features a decidedly lower-voiced Bieber. Ladies and Gentlemen, the sound of post-puberty Justin Bieber in his new song, “Mistletoe”:

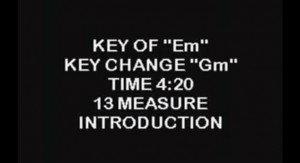

So how much lower did his voice get? Well, in musical terms, in this new song, he peaks at “A,” while in his 2009 debut hit, he reaches the “C” above the previous “A.”

Using these two songs–his biggest pre-change hit and his first single post-change–we can approximate his downward shift as a minor third. Which, in the music world, is quite a lot.

So what does this seismic shift mean for our young phenomenon? In practical terms, his old songs are unsingable in their original keys, which means that in order for him to sing them live, he’s going to have to sing transposed versions that are taken down a few notches to accomodate his new, lower vocal range.

And this is really sad. Because in doing so, the songs are, well, neutered. Allow me to explain why this is such a big deal after the break.

If you must sing "Livin' on a Prayer" at karaoke, at least do it in the proper key.

I actually complained about the neutering effects of transposing songs before on this site. While explaining The Karaoke Quotient, a formula for objectively determining the appropriateness of a song for karaoke, I made a big deal about being able to sing a song in its original key :

Soaring ballads and screaming metal songs kill singers with their range. Most men can’t hit those high notes in “Livin’ on a Prayer.” Bon Jovi himself can’t even do it these days (Ritchie Sambora does it instead). But note that I mentioned in the original key. Songs with high notes like “Livin’ on a Prayer” are often transposed down a step or two [for karaoke], which helps with singability, but kills in terms of remaining true to the feeling of the original song.

I didn’t cover it in too much detail in that article (as there were nine other parts of the formula to explain), so let’s do that now. If you’ve ever had the misfortune of coming across one of these transposed tracks, you may have noticed that even competent singers have trouble starting on the right pitch, even if there’s plenty of lead-in. After they’ve stumbled around for the first verse, they typically lock into the right key during the chorus, which just doesn’t get as high as it should. The energy and power of that impossibly high chorus is just sucked out of the song because we expect it to be, well, impossibly high.

It’s not just my personal theory on song keys and transposition, either. In the book This Is Your Brain On Music, author and neuroscientist Daniel Levitan describes an experiment in which he asked non-musicians to sing, unaccompanied, their favorite songs from memory:

The results were surprising: the subjects tended to sing at, or very near, the absolute pitches of their chosen songs. I asked them to sing a second song and they did it again. This was convincing evidence that people were storing absolute pitch informat in memory; that their memory representation did not just contain an abstract generalization of the song,but details of a particular performance.

In other words, almost all of us, musicians and non-musicians alike, are finely tuned to the particulars of a sound recording to the point that we can recall their melodies in their original keys without any help. So when we hear a familiar song with familiar instrumentation but in a different key, our minds rebel. We don’t enjoy the song as much as we would if it were in the original key. When the song is at a lower key and the high parts just aren’t as high, we notice that difference and interpret it as a reduction in the song’s energy level.

This is the problem that Bieber will face when he takes the stage with transposed lower versions of his songs. They just won’t carry the same punch that they used to.

Don’t believe me? Try this on for size. Here’s perhaps the most famous singer to manage the pre/post-puberty transition, Michael Jackson, singing “I Want You Back” in the early 1970’s with the Jackson 5:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_5hQ8cEE7Q

and here he is as an adult, singing the same song, but transposed down from A flat to D (four and a half steps, for those of you keeping musical theory score at home):

Yikes. Now, don’t get me wrong: the second version isn’t bad, but it’s different. And more importantly for Justin Bieber, it feels foreign to the artist. Like it’s…not his song anymore.

Which is actually true. It belongs to a different singer: a boy, not the adult man that the boy eventually became.

I used the word “sad” to describe this situation at the beginning of this post. And I meant it. That boy singer is lost and gone forever. He’s not coming back. The world will no longer be able to hear “Baby” the way it was meant to be performed live, in the key of E flat.

It’ll be interesting to see where Bieber takes his live show, and his career, from here. Even without the voice change, I’m sure there’d be an urgent need to produce new material, but that need must be greater now that he can’t rely on his old material to sustain a live show. Or maybe he’ll try to get by on transposed versions of old songs as a significant portion of his live show for many years to come. And maybe his legions of fans won’t mind the effect transposition will have on their favorite songs. The experiment I quoted, after all, was done well before our current Bieber-ified era.

But what about you, OTI readers? Are you bothered by transposed versions of your favorite pop songs? If you’re not a musician, were you even aware of such a thing before reading this? Sound off in the comments, especially if you can cite other example of artists significantly transposing their songs into lower keys and if people have noticed.

This is a significant and interesting article, and anything that quotes ‘This Is Your Brain On Music’ is a winner; what I’m interested in is the parallel puberty of the bulk of his fans (viz. Mark Lee. No, I mean – ) The ten and up girls and boys who have worshipped him as a modern day idol – there is a level of devotion to such acts these days that I can’t remember in my own youth – they seem the analogue of The Beatles and The Monkees. We’re beginning to see it in twitter trending topics and the like – the enforced sexualisation of these individuals. Bieber moving from hero to hunk, the man element does not merely change his voice – it changes how he is viewed. What will happen to those fans as they grow? Will they, like with the reformation of Take That, follow him to middle age and beyond? And what impact does this have on the relationships of those who have him as their post-pubescent paragon? If he is even slightly influencing the idea of MAN, of the desirable, lovable man, how will that impact American and global masculinity? If the condition of desirability for men is set by heterosexual women and homosexual men, will men adapt in a Bieber-ish direction? Is there a Bieber-ish direction at all? What does he promise in his songs and styling that man presently does not in general do?

I believe I need to study more sexuality, attraction psychology and gender studies before I can address these critical questions.

Also, is the answer not Autotune?

Yeah that was my first thought.

Listen to the songs – that difference is so huge, I don’t think autotune could hide it. It certainly couldn’t hide it in live performances. It’s not that he sings those high notes off key, his range is significantly lower and can’t sing them at all.

It’s not like he isn’t autotuned already anyway.

I mean, even if you could pretend his voice never changed, it would be really jarring and weird, an adult with a voice like that. He is selling his picture as well as his voice, and he totally doesn’t look like that old voice anymore – he has to reinvent his image.

And I don’t think Mistletoe really does it – this Bieber doesn’t really work. He needs to find something else.

Why, oh why, did he not get castrated?

Often, singers will cheat by either singing down an octave but louder, or by having backup singers sing the high note the lead can no longer hit, while the lead sings some harmonizing note underneath. Fans will notice the former, but not feel too cheated, and they’ll probably not notice the latter.

No, I am not bothered by transposed versions. I wish they’d do more of it on shows like American Idol- I’d rather hear a person with a lovely voice sing something arranged to fit within their range than reaching for and missing difficult notes or (worse) straining to reach every note.

One of the things that really struck me when reading Levitan’s book was an early passage about the physical purity of the way our brains process sound. I have a copy right here — let’s see if I can track down the actual passage:

That is one seductive piece of science — but does the purity of hearing mean we must expect that same consistency from the much-more-variable human voice? I’m a frequent karaoke singer, and I’ve noticed that my range tends to fluctuate with just about anything: hours of sleep, foods and beverages consumed, time spent talking, time spent not talking …

Bieber’s voice would have changed even if he’d hit puberty before he hit the big time — performance and practice take their toll. Like @Estarianne above, I’m in favor of a little transposition if it means the singer’s performance improves.

But also, there was one karaoke version of Journey’s “Open Arms” that I sang once, where they’d transposed it half an octave higher than usual — probably to bring it into a comfortable range if you were a dude singing an octave lower. But I couldn’t sing it an octave lower and had to go screechy and shrill instead. I felt betrayed.

So — transposition within reason, and not without warning?

Having been subjected to a ton of

top-fortytop-four pop music by my recently pre-teen daughter I have to agree with Timothy, above: if his voice is much lower now it just means he can start singing through autotuners the way… pretty much every other major/popular non-rap adult male artist except Bruno Mars does.I assume he avoided the seemingly obligatory autotuners before his voice changed because they would have made him sound like Alvin and the Chipmunks.

Should Beiber choose to forgo autotuners I expect that, since he really does seem to be a vocal artist and not just a mop of hair I expect he’ll do what older musicians do as they age and reinterpret their older repertoire to not only reflect their new voices but their artistic maturity.

—

As for vocal ranges and the toll pro singing takes, earlier tonight I happened to be browsing various videos of Adele’s “Someone Like You” and even she doesn’t go for the high notes on any of her live/on-camera versions.

—

And finally, possibly because I’m more used to garage bands and bar bands doing covers than I am with either pop music or karaoke I’m… eh, I’m probably not the one to be judging whether songs only sound good in their original keys. Live bands with better performers seem to select the lead singers’ sweet and/or power pitches rather than the original key.

figleaf

If you think that Justin Bieber isn’t autotuned, you are wrong. Most people who aren’t in the industry don’t know that autotune is more subtle than most people think. Everyone seems to just think of T-Pain sounding like a robot but autotune can actually be used as an after-effect to simply touch up a single pitch or even a part of a pitch. The effect becomes more and more disconcerting the further the autotuned interval is from the original pitch and the longer the effect is sustained. Bieber is autotuned but because of the excellent production, we don’t notice it; however, if Bieber was autotuned up a whole minor 3rd, which the writer of the article suggests is the interval his voice has dropped, we would definitely notice.

In terms of my own experience with changes of key, I have played in a number of groups that have played and recorded cover songs. It is very common practice to change the key of the song to match the vocalist but, in my opinion, the change is always a negative one. Songs are usually in their original key for a reason. The timbre of a particular person’s voice at particular frequencies has a lasting impression on the listener(s), as Levitin states in his book “This Is Your Brain on Music”, and it is a shame to have that aural memory erased. For karaoke, it can be as disconcerting as listening to a song autotuned the whole time. To the trained listener or someone with perfect pitch, there might not be a difference at all.

The subtleties of performance are lost with autotune and the effect that a song has on people can be lost with a change of key, as well. Certain frequencies just seem to resonate with us more and that’s something we should avoid losing.

Yeah, certainly it’s clear from U Smile and Baby that the voice is subject to a certain ‘smoothing’ effect.

So we’re all on the same page w/r/t Autotune here:

Autotune will not help JB sing “Baby” in its original key of E flat major if those high notes are now out of his range. It’s not possible for AT to let him sing it in a comfortable, lower key (e.g. C major) but make it sound like E flat major to the audience. Nor would AT allow JB to sing the high notes in falsetto and give them the same oomph as if here were singing with his full chest voice. (At least to my knowledge).

Glad to see this has sparked a healthy discussion and to see that there are other people who care about transpositions as much as I do!

You’re right. Autotune and other pitch-correction/shifting software can raise the pitches to the original key but they will sound distorted to the audience, similarly to the “Chipmunk” effect someone mentioned above which raises the pitch up one whole octave. On instruments such as guitars or keyboard this type of effect can sound interesting and is used for guitar harmonization and the like but on a vocal, it sounds foreign and robotic. Also, if we are talking about live performances, it most certainly wouldn’t work. As disconcerting as it would be to the audience to hear a song shifted up a large interval, imagine the performer trying to sing in a different key than the song that they are hearing. It would be near-impossible and would sound fake.

Key certainly has an effect on the way we hear music. I play a sad somber version of “If I only had a brain” two whole steps down, and the drop in key helps the listener’s brain make the transition from the previous perky version. I heard Elvis Costello and Bill Frissel try the same thing in it’s original key, and it didn’t really work.

Change in key isn’t always a bad thing.

Transposing a song down a half step or even possibly a whole step isn’t a big deal. When it gets to be bigger than that, it becomes really noticable

It’s not really a big deal to transpose down by 1 semitone. Bon Jovi’s done everything like that since 1988. It’s only problematic when the key is significantly lowered (i.e. The Police doing “So Lonely” a major fourth down)