The Well-Made (Video Game) Plot

The Well-Made (Video Game) Plot

Video Game plots, if they’re meaningfully interactive, have some features of the whodunnit, the whendunnit, and the dunnwhat. Like a whodunnit, the central question is presented in multiple choice format. But like a dunnwhat, the question is basically what the protagonist is going to do. Finally, like a whendunnit, the questions that the reader/player cares about are always going to be different from the questions that the character/avatar cares about.

In order for the interactive narrative to function as a game, there need to be “right” and “wrong” decisions. In practice, there are usually several layers of this. Most wrong are actions that the machine doesn’t even understand (like pressing left to make a choice rather than pressing A, or balancing the controller on you head or whatever). Slightly less wrong are actions that lead you around in a circle: “But thou must!” responses, although often the circle is a longer and more enjoyable ride than that. Least wrong are actions that meaningfully advance the plot. And these in turn, in works with branching plots, are divided into the decisions that lead you into “good” and “bad” branches (here defined as more interesting and less interesting rather than good and evil, or happy and sad, although game designers usually make those synonymous).

The player’s experience of the game’s plot can be abstracted to exploration of the decision tree, and discovery of the “good” actions on that tree. These processes are linked: failing to discover the right choice will always mean exploring a wrong one. And in some games, at least, the wrong choices are designed to gently point you in the direction of the right one. These are the games we can call well-made.

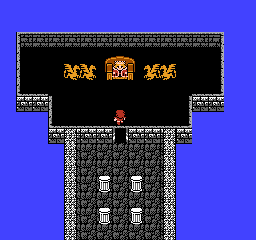

Might this guy have something interesting to say?

A well-made plot in fiction is one where the central mystery of the story can be figured out in advance by a smart and attentive reader based on cues provided by the text itself. The same holds true of video games. A game with a well-made interactive plot is one where the game itself leads you to the most interesting branches of the decision tree. There are dozens of ways to pull this off, depending on the kind of game you’re looking at. If it’s a conversation tree you’re dealing with, you can make one of the good choices contain a highlighted keyword the player will remember from an earlier conversation, or make one of the bad choices transparently inappropriate, or make the response to the wrong answer something that should prompt the player to offer the right answer. But if it’s a game of “find the NPC with something important to say,” well-madeness is going to be a function of architecture: either the character should be in a central location — on a throne at the end of a long vertical hallway lined with columns, for instance — or somewhere notably out of the way, but not actually hard to find, like at the bottom of a well. If it’s a game of “optimize my character’s build,” it’s done by making the useful powers seem cooler than the useless powers, or more frequently by showing the math and letting the munchkins work out the percentages on their own. And with any kind of game at all, you can always break the fourth wall: “Smoke your pipe to summon the wizard!” The point is that an attentive player should be able to arrive at the solution by something other than chance or brute force.

Unlike the literary version, well-madeness in video game plots is a feature of the small scale, not the large scale. It might be that we should think of games not as having well-made plots, but as having a number of discrete narrative puzzles, each of which can be well-made (or not). Z doesn’t have to connect to A. It can, certainly, and maybe it should, but this has more to do with thematic unity than with a sense of narrative fair play.

It should be remembered, of course, that a well-made plot is not synonymous with a good one. A well-made mystery novel can easily go wrong by giving the reader too many clues, so that there’s never any doubt who the killer’s going to be. In video games, this manifests as hand-holding, spelling out in blatant detail what the right choices are and making all of the mazes into branchless tunnels. These plots are still well-made, they’re just dull. Making them less dull is a question of balance, and of preserving illusions. If I guess the solution to a well-made detective novel, I have no reason to feel smart. The author gave me all of the clues, after all! But if it’s balanced well, I maintain the illusion that I put it together on my own. If I figure out the right way to progress in a well-made game, I have no reason to feel like I’m good at playing it! The programmers told me what to do. But if it’s balanced well — if they mainly relied on contextual cues, and making the right choices look fun — I maintain the illusion that my actions are freely chosen. A plot that’s both well-made and enjoyable falls into this sweet spot.

And of course, all of this only applies to video game plots that are interactive. Many games have no plots at all. Many that do have plots give the player no control over the plot whatsoever, limiting it to scripted cut-scenes at the end of certain levels (although we could talk about the degree to which the level itself, even in a side-scrolling platformer, has an elementary narrative goal of some kind: “find the exit”). But although people often talk about the distinction between plot and narrative in gaming, there are cases where the plot itself is a game (which means that most pieces of entertainment software are actually several distinct but interlocking games — Super Mario RPG, for instance, has a rhythm game, a resource management game, and a game of narrative exploration/discovery, at a minimum), and when we talk about how well these are put together, we need to judge them by criteria of their own.

Great essays. What do you think about games being designed to be open-ended enough that players may read a plot into their choices- choices with no wrong answers leading back to square one? This seems to be an aim of Elder Scrolls and Mount and Blade. In these cases the presence of a plot is a choice of interpretation and performance by the player.

So…is that series of super awesome Cowboy Bebop articles just like dead now or what? Because that would suck.