Tension

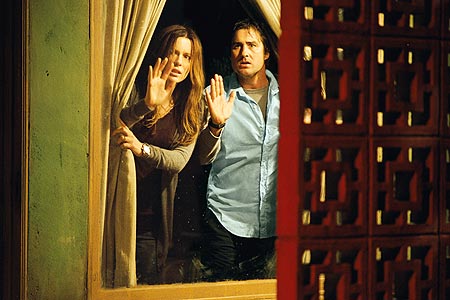

Despite these similarities, there are two big important ways that these kinds of stories differ from each other. One has to do with the role of the protagonist. In whodunnits, the reader has to match wits with a detective character who is also trying to solve the mystery. The detective serves as both a rival and a point of identification for the reader. We’d like to beat them to the punch, but we understand that they’re on our side. They feel about their world the way we feel about their world, the same desire drives them as drives us. In whendunnits, contrariwise, the reader is and must be on their own. We get to try to solve the whendunnit because we stand outside of the work’s timeline. Kate Beckinsale doesn’t get to know ahead of time that the car is going through the lobby. Uma Thurman may hope to Kill Bill, she may plan to Kill Bill, she may even be convinced that she will succeed in Killing Bill, but she doesn’t get to know that “Uma Thurman Will Kill Bill” was the tagline of the movie. The question for us is when/how, the question for her still has to be what/whether. Whodunnits and whendunnits are on the opposite ends of a spectrum here. “Normal” plots fall somewhere in between. In most cases, the main characters don’t themselves know what they are going to do (or, for the psychological variant, who they really are), which puts them in the same shoes as the reader. But they may or may not care about it. There’s a very narrow subset of the novel of psychological revelation in which the character is actually trying to figure out who they really are, but in a great many cases they are simply going about their day to day business as a funeral home director, stick-up artist, or heir-apparent to a motorcycle gang. The actions which are psychologically revealing to the viewers are to the characters completely unrevealing.

The non-psychological dunnwhat, which is more about physical action, tends to work more like a mystery novel. Arya Stark wants to get home to Winterfell, but she doesn’t know what she has to do to make that happen. The readers want her to get home to Winterfell, and we don’t know what she has to do to make that happen. This kind of identification often slips back and forth a little bit — either we have information the character doesn’t, leading to dramatic irony, or the character makes a preparation that the author doesn’t share with us, leading to antidramatic irony — but for the most part it holds fast. You could notionally imagine a text where a the reader wants to know what the characters will do, but the characters themselves are ambivalent… The Manchurian Candidate, maybe, sort of? The Neil Gaiman Miracleman? Weekend at Bernie’s? But as you can see from the examples, this requires some rather special effort on the author’s part.

The second big difference between these narrative forms has to do with the degree of narrative constraint. Reverend Knox’s very first rule for a well-plotted mystery demands that the killer turn out to be a character introduced within the first few chapters of the story. Unless these take the form of a phone book, then, a well plotted whodunnit will present you with a sizable but strictly limited number of solutions right off the bat. Every character who is introduced could be the killer, but only these characters are allowed, which means that — like in a game of Clue — you can narrow down the possibilities over time and get invested in one possibility over another (a bad idea, in Clue, but possible). For whatever reason, the fewer possibilities there are, the more intense our desire to know becomes. It’s as if there’s a certain amount of water, flowing through a network of pipes, and as you close the valves on more and more pipes the water pressure in the rest of the system mounts and mounts and mounts. The climax comes when there’s only one viable choice remaining… but note that this is not sustainable; it’s a moment, not a condition; if you wanted to extend the plumbing imagery, this would be the point where the pipe bursts and starts spraying raw narrative tension all over the shag carpet in your allegorical rumpus room. So ideally you wait right to the end before letting this happen. Also, you generally want the rate at which potential murderers are eliminated — at which valves are shut off, like — to increase rather than decrease over the course of the novel. If there are twenty suspects, and seventeen of them die in the first ten pages of a two-hundred page book, that’s a problem. It’s also a problem if they’re all viable suspects up until ten pages from the end, at which point, again, seventeen of them die. You want to eliminate suspects at a steady rate, or on a gently accelerating curve. And writers really get in trouble when they think they have two viable choices, but one of them is quite clearly not the guy — and then this gets extended for hundreds of hundreds of pages, resulting in, burst pipes, flooded basement, water damage, nasty mildew infestation all up in your crawl space. (Take the whole Team Edward/Team Jacob business, just for instance.)

Whendunnits like whodunnits are constrained, but in a rather different way. As soon as the meter drops on the plot proper (after the stakes have been established in the flashback, that is), the crucial event could happen at any time: if the plot flashes back exactly one hour, then you’ve got exactly sixty minutes in which the events could occur. But if they happen right away, the tension is basically zero, so nobody’s going to write it like that. If you wait thirty minutes, that tension will build: now you have only thirty minutes for the event to happen in! And if you wait forty minutes? If you wait fifty? Any storyteller worth their salt, of course, will save the events for the fifty-eighth or fifty-ninth minute. Just like whodunnits reach their peak intensity when you have the smallest number of potential criminals, whendunnits reach their peak intensity when the window that the crucial actions can fall into is as small as it possibly can be. There’s something like an unexpected hanging paradox going on here, of course, but in practical terms this matters little. We can safely assume that the important events in a whendunnit are always going to happen within the last twenty pages of the book or twenty minutes of the film, but knowing this does not protect us from experiencing the increased narrative drive: “Oh okay, I get it, here it comes, here it comes!” Once you’ve figured out the underlying narrative logic, it becomes clear that whendunnits don’t technically need to have flashbacks. All you need is for the readers to have some knowledge of future events that the main characters don’t have, and for there to be a limited time frame in which these events can occur. We know that the Power Rangers will destroy the rubber-suited monster of the week, we even know how — that one big diagonal slicing move with the power sword. All we need to know is whether it’s time for it to happen yet in this episode, i.e. when it will happen. And one of the interesting corollaries of this is that all whodunnits are also whendunnits. The detective will figure out who the killer is at some point, because it’s generically required. As you get closer and closer to the end of the book, the time window (expressed here as a matter of page count) during which this can happen gets smaller and smaller — and as a result, the intensity of the experience gets stronger and stronger. Very often, these two kinds of narrative drive appear in a single work, so that the shrinking subject pool and the shrinking window of opportunity are neatly superimposed. It’s not just in detective stories either — one particularly clear example of this is the flashback-structured romantic comedy Definitely Maybe, where we know that Ryan Reynolds has had a child with one of his old ex-girlfriends, but not which one.

Compared to these humming narrative engines, the relatively open-ended structure of the serious novel, in which a vividly realized character merely does… something… falls a little flat, which is part of why these books are typically not page turners. Adventure stories, dunnwhats that are page turners, get around it by providing constraints on their narratives in a different way. Rather than setting up a situation where the character has no predefined teleological goals, they set up a very clear goal which may or may not be attainable. They are not dunnwhats but dunnwhethers. Frodo will toss the ring of power in the volcano… or not. Lizzie will marry Darcy… or not. Tony and Maria will find a place for themselves, somewhere a place for themselves… or not, although arguably in this case we already know that they’re doomed, and it’s just a matter of learning when and how they succumb to that doom. Narratives of this kind present us, like the whodunnit, with a multiple choice question, and therefore are typically considered more frivolous because real life mostly slaps us with short essays. Many, many romantic novels, serious or trashy, have their heroines choosing between two or three guys — but in real life, it’s never that neat. Rather, we face the implied choice between all guys, everywhere, and of course there’s a very real chance that even that queasy pseudo-choice will be made meaningless by factors beyond our control, such as whether the guy we choose is even interested, or whether he’ll get hit by a bus tomorrow. Some life decisions really are unambiguous choices with meaningful results. Plead guilty, or innocent? Accept the marriage proposal, or reject it? But these moments — which we might describe as narratively exciting life experiences — are pretty few and far between.

So to summarize, before we move on to some actual video games:

• Well-made plots require a sense of long-term causality, or fate. Typically they involve a who, a what, a when, a where, and a why, but some of these elements are unknown at the start of the story. A smart reader should at least technically be able to work out the missing pieces ahead of time.

• In non-interactive fiction, at least, we can distinguish between plots that primarily that are primarily about finding out who did some known thing, plots that are about finding out when some known future event will happen, and plots that are about finding out what some known person will do. (There are probably other categories — figure them out for yourselves. Could you imagine a pure howdunnit? )

• In some kinds of stories, the main characters care about the same questions that the readers care about. In others, they almost never do. This has a pretty big effect on our experience of the work.

• For all of these categories of plot, constraints on narrative tend to make the narrative more exciting. Which is not to say better, necessarily…

• There’s often both a plot and a meta-plot at work, so that on one level, we’re wondering who the killer is, and on another, we’re wondering when the detective will figure out who the killer is. Ideally both levels of this should be well-made: if we feel like the detective identified the killer only because the episode was about to end, that’s a non-trivial weakness.

I expected more discussion of plot-driven games, like Red Dead Redemption, LA Noire, or Uncharted. Maybe in Part 2?

Awesome. Bonus points for mentioning Encyclopedia Brown.

There are mystery plots that could qualify as “pure howdunnits,” where the detective knows the identity of the murderer, but the murderer has an airtight alibi, so the detective must figure out how they managed to kill someone while they were live on national television/having dinner with the president/in outer space.

Monk used to do a lot of these, and they crop up on other television shows as well. I think they lend themselves better to an episode of TV; we already know who the killer is, so they’re less suspenseful, which makes it hard to stretch them out for a 300 page novel but you can pretty comfortably fill 40 minutes of airtime. Also, it’s a way to shake up the formula and keep audience’s interest when a show’s on its 60th episode, without totally abandoning a show’s “crime solving” raison d’etre.

Other “pure howdunnits”: locked-room mysteries (for instance Stephen King’s Holmes pastiche), stories about games (we’re reasonably sure that Bobby Fischer, or Yugi, will prevail, but the drama lies in discovering what method of victory they will use), and several Asimov short stories where we know exactly what happened (when, where, who, why) but not what science-fiction technology was used to accomplish the task.

here are some reference links just in case you want to know more about the “academic” side of narrative and gameplay and etc.

http://www.ludology.org/articles/Frasca_LevelUp2003.pdf narrative vs. gameplay, very easy to read I promise!

and also too it sounds like you are searching for the term “procedural rhetoric” http://www.bogost.com/books/persuasive_games.shtml

“Video games are only ever dunnwhethers, and rather than caring about the characters’ actions, we care about our own skill.”

“The major constraints we deal with when we play video games — and this should be painfully obvious to anyone who has ever played video games — are the constraints of our own skill. That’s the struggle, and the primary excitement, that we take away from the experience.”

I feel like you’ve characterized a certain kind of player, rather than the nature of the game itself. I don’t see why, because this media is more interactive than television or books, the player is inherently more concerned with her own skill than the characters or plot. I say this because I *do* become invested in the characters that I play or interact with.

Two games that immediately jump out as being not particularly skill-driven but (for me) very enjoyable as an interactive narrative are Arkham Asylum and Mass Effect 2.

The perfect videogame plot is The Warriors. The film, not the book. We know who are protagonists are. They have a firm goal, lots of enemies, and a time limit. You don’t need anything else.

It’s funny you should mention that http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Warriors_(video_game)

For films, The Prestige is I think a great example of twin howdunnits in direct opposition.

Dunnwhethers frivolous? Has Moby Dick ever been called frivolous? Have the story of Siddhartha Gautama’s enlightenment, the Ramayana, the story of the Fall, or the passion of Jesus been called frivolous? Within your schematics, the only place I could find for these plots is as dunwhethers. Perhaps I have misunderstood your meaning.

I think it would be a pretty big mistake to see Moby-Dick as primarily “about” the question of whether or not Ahab will successfully kill the whale. And the rest of the examples you list are religious texts, which generally are considered “serious” for reasons other than their plots.

But you’re probably right that the serious/frivolous distinction I’m setting up is a little forced. I do think it holds up as a general rule, but I’m happy to concede that there are exceptions.

“In grand narrative terms, Edgar doesn’t matter.”

Actually that’s entirely untrue. Edgar is a central figure to the game’s background story (he’s a member and primary funding source for the Returners organization that the whole first half of the game revolves around), his fancy sandcastle’s abilities serve a narrative function three times in the story, he’s a required party member for some sections of the plot, and in the sandboxy second half of the game he’s one of only four characters the plot demands you gather up before taking on Kafka.

Now if you’d said this about Gogo or Umaro you’d have had a point, but definately not for Edgar.

I disagree. Edgar is certainly more important than Umaro and Gogo (and, I would argue, more important than Setzer, Gau, Relm, and a whole bunch of other characters). But that doesn’t necessarily mean he actually matters. In traditional narrative terms — which are not necessarily appropriate for judging games, but they’re what I’m talking about at this point — the game is about Terra finding out who she is, learning the Empire’s evil plan, and thwarting it. Everything else is a picaresque episode (including the whole second half of the game except for the final boss fight). Saying that these parts are unimportant is a little misleading: the game’s plot is a picaresque, so these episodes are arguably the most important things. But if we look for a well-made plot in the game, Edgar (along with a lot of other stuff) becomes window-dressing. Yes, the castle comes back. Do any of its appearances matter? Really? The second one lets you get Edgar as a character again, which is only important if you think he’s important. The third gives you access to another dungeon — completely optional, I think? — which it literally collides with at random. They could just as easily have put the dungeon the bottom of the ocean or on top of a mountain. So yes, the castle serves a mechanical purpose in the plot, moving from B to C and from H to I or whatever, but there’s no sense in which it helps build up to Z. Same with the Returners, I’d say — I don’t think they’re nearly as important to the plot as you do. I can only speak for myself, of course, but I lost track of the fact that my party was supposed to be part of a paramilitary resistance group VERY quickly indeed.