[Enjoy this guest post on Tommy Wiseau’s The Room – no, wait, come back! – by Raquel Steres.]

Writer/director/actor/producer Tommy Wiseau’s The Room is, at least on the surface, a simple romantic drama about a love triangle. Boy of indeterminate national origins meets girl. Boy and girl become engaged. Girl gets bored. Girl has affair with boy’s best friend. Boy finds out, destroys apartment in a lethargic rage, and kills self.

The film’s infamy does not come from its simple plot, but from Wiseau’s unique style of filmmaking. The Room is not what a film is supposed to be. Characters appear with no introduction and leave the film with no explanation. Major plot points happen off-screen while a sizable portion of the film’s running-time is devoted to scenes of characters buying flowers, ordering pizza, playing catch with a football, or greeting each other with a pleasantly surprised, “Oh, hi!” Dialogue does not even attempt to approximate the patterns of actual human speech. Actors constantly step over each others’ lines, which seem to have been arranged out of order. Characters switch emotions wildly and arbitrarily. The main character’s apartment contains no family photographs, but is instead decorated with framed pictures of spoons. Every single shot in the film is slightly out of focus and off-center, due to the fact that Wiseau could not decide whether to record The Room on 35mm film or HD video and chose instead to shoot in both formats simultaneously by taping two cameras together.

It would be easy to assume that all of these elements are mistakes. All the people involved in the film’s productions were amateurs, utterly inexperienced in acting, directing, cinematography, editing, costume design, catering, and all the other essential aspects of filmmaking. The film is, by any standard, mesmerizingly bad.

But a closer investigation of The Room’s production reveals that every one of Wiseau’s choices was deliberate. A search of Youtube turns up earlier versions of the film’s pivotal scenes. Wiseau workshopped these scenes, practiced them, revised them, refined them over a period of years, and without exception, the rough drafts are better than the final product. The dialog is more natural, as is the blocking. The acting is humanoid, even competent. Wiseau could have made a normal film, but he didn’t. He chose not to. He made The Room on purpose.

Recognizing this fact is the key to understanding what The Room is really about, which is far more than a simple love triangle. The film is actually a religious morality tale about the struggle between hedonism and salvation.

Oh, hi Mark.

Perhaps the film’s most striking element is its central character, Johnny, played by Tommy Wiseau. Johnny is an odd figure. His unusual appearance, with his muscular yet lumpy physique and his hard face, is not typical of that of a traditional leading man. His mumbles in an unidentifiable accent and never reveals his nation of origin. He has no family. He speaks in broken idioms and simple declarative sentences and is incapable of picking up on innuendo or connotative language. He laughs at inappropriate times.

Though apparently advanced in age, he displays startling naiveté at the ways of the world. He does not appear to understand that employers make empty promises, that women change their minds, that audio tapes have limited storage capacity, that people lie, and that apartments should be locked when the occupants are not at home.

Despite all this, he manages to hold down a job, support himself and his fiancée Lisa in a San Francisco loft apartment (the titular Room), and pay the tuition of Denny, a young man-boy-thing who lives somewhere nearby. He has managed to amass a large circle of friends and acquaintances despite his total lack of social skills. Johnny is even able to subdue a gun-toting drug dealer, unarmed. The other characters heap praise upon him.

Many of those who have seen or reviewed The Room suggest that Johnny is not human. This is no great revelation. Johnny all but confesses openly to this, shouting, “Everybody betray me [sic]! I’m fed up with this world!” in a tense emotional scene. So now we know one thing: Johnny is not from Earth. He is not human. We have to ask: what is he?

Consider Johnny’s generosity and naiveté. Consider his fascination with ordinary objects like spoons and doggies. Consider his (and by extension the film’s) preoccupation with the minutiae of life and odd sense of time.

Now consider the following exchange from 1987’s Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire in the United States, later remade as City of Angels with Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Z1kE5nkuB4

Damiel: It’s great to live by the spirit, to testify day by day for eternity, only what’s spiritual in people’s minds. But sometimes I’m fed up with my spiritual existence. Instead of forever hovering above I’d like to feel a weight grow in me to end the infinity and to tie me to earth. I’d like, at each step, each gust of wind, to be able to say “Now, now and now” and no longer “forever” and “for eternity.” To sit at an empty place at a card table and be greeted, even by a nod. Every time we participated, it was a pretense. Wrestling with one, allowing a hip to be put out in pretense, catching a fish in pretense, in pretense sitting at tables, drinking and eating in pretense. Having lambs roasted and wine served in the tents out there in the desert, only in pretense. No, I don’t have to beget a child or plant a tree but it would be rather nice coming home after a long day to feed the cat, like Philip Marlowe, to have a fever and blackened fingers from the newspaper, to be excited not only by the mind but, at last, by a meal, by the line of a neck by an ear. To lie! Through one’s teeth. As you’re walking, to feel your bones moving along. At last to guess, instead of always knowing. To be able to say “ah” and “oh” and “hey” instead of “yea” and “amen.”

Cassiel: Yeah, to be able, once in a while, to enthuse for evil. To draw all the demons of the earth from passers-by and to chase them out into the world. To be a savage.

Damiel: Or at last to feel how it is to take off shoes under a table and wriggle your toes barefoot, like that.

Cassiel: Stay alone! Let things happen! Keep serious! We can only be savages in as much as we keep serious. Do no more than look! Assemble, testify, preserve! Remain spirit! Keep your distance. Keep your word.

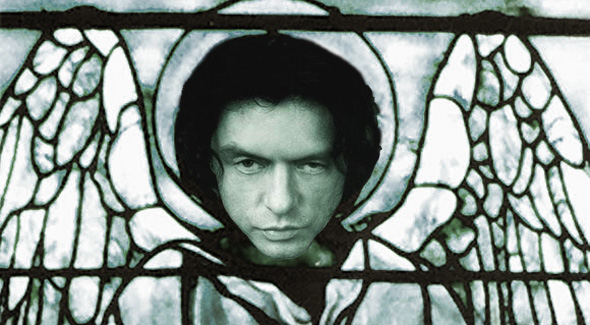

The above clip features two characters, Damiel and Cassiel, discussing their fascination with quotidian human life. Damiel and Cassiel, like Johnny, are thrilled by the idea of reading a newspaper or feeding a cat. Damiel and Cassiel, like Johnny, like to say, “Oh,” and “Hi.” Damiel and Cassiel, like Johnny, do not understand the passage of time or know what it means to tell a lie. Damiel and Cassiel, like Johnny, are not human. Instead, they are spiritual beings. They are angels.

During the course of Der Himmel über Berlin, Damiel falls in love with mortal life and a mortal woman. At last, he abandons his heavenly existence for a human one. (He is not the first angel to do this; it is implied that Peter Falk — not Falk’s character, but the actor, Peter Falk, playing himself — went through a similar transition.) The film’s dénouement finds Damiel enjoying his new life, having successfully bridged the gap between spirituality and sensuality.

Where Der Himmel ends, The Room begins.

In a way, The Room is a spiritual sequel to the German film, following the existence of an angel some years after taking the plunge and becoming a mortal man. The Room hints at Johnny’s celestial origins when Lisa says to him, “You think you’re an angel. You’re just like everybody.”

But while Der Himmel finds the change a happy one, The Room takes a much more cynical view. The theme of incompatibility pervades all of the film. Over and over again, we see characters try to make two disparate elements coexist, and fail. A woman tries to have two lovers at once. A customer in a coffee shop orders a slice of cheesecake and a bottle of water. Johnny’s fiancée serves him a cocktail that the film’s fans have dubbed “Scotchka” — a putrid mix of equal parts whiskey and vodka. In another scene, Lisa orders a pizza: half Canadian bacon and pineapple, half pesto and artichoke. The two toppings cannot mingle; at best, they can hope to cautiously share the same plane, like a pair of cameras strapped awkwardly together on one rig.

But they can’t coexist. Not really. Not for long. The human race cannot truly reconcile spirituality with sensuality. When given the option, humanity (represented here by Johnny’s fiancée Lisa) will choose simple, mindless hedonism (represented by Johnny’s himbo friend Mark) over spiritual fulfillment (represented by Johnny himself, the fallen angel). This presses Johnny and Mark to fight; not only are the spirit and the flesh incompatible, but they are actively at war with each other.

Johnny realizes he cannot bridge the gap between heaven and earth. It is then that he utters the famous line, “You are tearing me apart, Lisa!” He can no longer reconcile the body and the soul. They fall apart. The center cannot hold. Johnny gives up on human life and heads back to heaven via a bullet to the head. But before he goes, he wrecks the apartment, the titular Room.

You are tearing apart the tenuous connection between corporeal sensation and religious ecstasy, Lisa!

A word about the room. In a DVD special feature, Wiseau hints that the room is much more than a physical living space. He says, “It’s not a room. It’s the room.”

The room is, as previously discussed, a loft apartment in San Francisco. The upper level of the apartment, reached by a spiral staircase, contains a bathroom and bedroom. The large four-post bed is dressed in white sheets and white curtains. This is where Johnny and Lisa sleep and make love. This is where Johnny goes to take his own life. This is the kingdom of heaven.

The main living area on the lower level is bathed in the sensual color red, with red walls and red candles. A coffee table sits before the couch, holding an altar-like arrangement of candles and a big bowl of apples, which bears obvious religious connotations. This is the room where Lisa seduces Mark, where Johnny celebrates his birthday, where Johnny and Lisa share pizza and Scotchka. This is the earth.

Johnny flees this room and destroys it.

Like any religious parable, The Room carries a message: repent, for the end is nigh. When the human race at long last abandons spirituality, the heavens will respond in kind, forsaking the land, snuffing out the candles, tearing down the walls, and smashing the spoon paintings.

[Does the scene where everyone plays basketball in tuxedos signify the camaraderie among angels prior to the Fall? And what about the Nic Cage / Meg Ryan remake? Sound off in the comments! – Ed]

Raquel Steres is an English instructor, freelance writer/editor, bartender, and high priestess of the Esoteric Order of Dagon. She lives in upstate New York.

You know…that makes sense.

I haven’t seen the movie, but I doubt a fallen Angel would represent spirituality or that an Angel would take its own life. More likely he is the spirit of something, “the 90ths”, America, youth or somesuch.

If the two cameras being shot side by side represent the impossibility of Heaven and Earth to share the same space, how will that theme change once Wiseau finishes the 3D conversion and the two views are in fact existing simultaneously in the same space, not just cautiously but indeed an essential combination for without which there could be no space, no third dimension, no “room” if you will?

I ponder the movie will then be from the point of view of some being that bridged the gap witnessing characters who can’t. Thus by having the audience in a 3D “room” manifested of the very joining of Heaven and Earth the characters either can’t see or try desperately to maintain the film finally takes on all the tragic weight and intended irony Wiseau wanted but couldn’t get because technology hadn’t caught up with his genius. It’s still tragic but more optimistic reading in 3D.

That then, is New Jerusalem descending and Kingdom Come. Right? Right?

Absolutely. I guess it doesn’t do much to truly settle the debate if New Jerusalem is a real place or is figurative. Like that 3D “room” is really there it couldn’t exist without Earthly materials, but it’s an optical illusion and won’t protect you from the physicality of rain or stray footballs.

It doesn’t exist in one sacred place, it can be shown/exist/reproduced in many places at the same time- with the right equipment, it’s sacredness isn’t solely connected to it’s scarcity of location. But once that 3D “room” stops being projected it’s physicality is lost.

That reproducibility/loss is at the core of it’s sacredness. Like how we’re only one with God when God is no longer one with Himself, our experience of the distance from God is what unites us.

So perhaps the loss of the physical 3D New Jerusalem leads us to appreciate the figurative notion which is the true New Jerusalem that we enter when the movie ends. The medium of the movie itself echoing Johnny’s tragic return to Angelhood, an angel inhabits Earth as The Room inhabits light on a screen.

Not to mention that 3D is still oddly flat-looking compared to real life. (To me, the different 3D depths just look like layered flat objects, like background scenery in a stage play.) So I think that what Wiseau is getting at here is that forcing a marriage between the spiritual and the profane will get us, at best, a flat, awkward approximation of sacredness or depth that doesn’t hold a candle to the real thing.

I concur. An instance within the movie’s text is the odd/goofy spoon paintings, here Wiseau underlines his rejection of the post-modern notion of “the real thing” being nothing more than the interplay of appearances, when Johnny smashes the spoon paintings it’s a symbolic castration of “the real thing” (false spoon idol) that makes room for The Real Thing (God.)