USA! USA! USA!

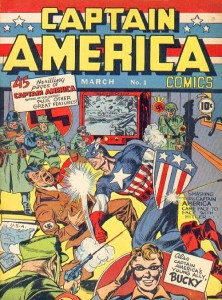

The basic Captain America story isn’t supposed to be complicated. Steve Rogers is a nice kid from Brooklyn with a heart of gold and unfailing sense of duty who turns into a Super Soldier and fights ze eehvil Ghermahns during World War II, the Least Morally Ambiguous War ever. Along the way he loses friends and gets the girl, but stays true to his patriotic duty to his country.

Future iterations of Captain America would struggle mightily with morally ambiguous situations and the symbolic burden of being the mascot of a nation-state whose actions he doesn’t approve of, but none of that is even hinted at in Captain America: The First Avenger. Most of this is due to its setting in World War II and that it’s an origin story focused on the creation of a hero. But even with those two factors as a given, the movie takes great care to steer clear of anything even remotely controversial. Even the gravitas of Nazi evil is mostly pushed aside by the fictional HYDRA, a rogue Nazi science unit that breaks off from the Third Reich and even targets it as one of its enemies. Rogers recruits African- and Asian-American members for his team, but the racial prejudices that both men would have surely endured are never mentioned in the movie.

USA! USA! USA!

From a story telling perspective, the movie made the safe choice by not bringing in these more complicated, challenging elements. The movie stays lean and focused on Rogers’s transformation and heroics, and everything else is in support of that. It make sense to show Rogers’s guilt over his friend Bucky Barnes’s death, but it probably wouldn’t make sense to see Rogers have an argument with Gabe Jones, the African-American member of the team, over segregation back home and abroad. It’s not essential to the story.

I recognize all of that, and yet, I can’t help but be a little disappointed that Rogers doesn’t have to struggle with anything beyond personal loss and HYDRA-thwacking in this movie. It’s justified for all of the reasons I cited above, but I can’t help but yearn for these things. This is OverthinkingIt.com, after all, and it’s not exactly in our nature to let any movie off the hook, especially when the movie’s hero is presented as the physical embodiment of a complicated nation-state, and as such demands the same level of scrutiny and debate we give to that most complicated of nation-states, America.

So with that in mind, let’s engage in a thought experiment: how could a different Captain America movie put our Star Spangled hero into some more thought-provoking situations?

Captain America as a Holocaust Movie?

What Would Captain America Do?

Rogers arrives in Italy in November 1943. This may or may not have been intentional on the part of the filmmakers, but either way, the choice of time and place give Rogers plenty of distance, both spatially and temporally, between the horrific scenes discovered by US troops as they liberated concentration camps in Germany in the spring of 1945.

But what if the timing were different? Putting the HYDRA threat aside for a moment, what if the U.S. government saved Rogers for the D-Day invasion and the final push into Germany? What if Rogers had come face to face with Nazi mass murder and all of its implications?

The testimonials of American GIs who liberated the camps are well-document. They reveal a range of strong emotions: shock, horror, trauma, and even guilt that they somehow weren’t able to do more to stop these atrocities from happening.

Now, remember that the doctor who invented the Super Serum implied that the formula affects the mind as well as the body. What was bad be comes worse, what was good becomes better. Schmidt’s bad personality traits amplify and turn him into a super-villain. Rogers’s good personality traits amplify and turn him into a super-hero.

What Would Magneto Do?

Given these augmentations, Rogers would have had an intense reaction to the concentration camps. Perhaps he would have been paralyzed by the evidence of man’s seemingly limitless capacity for cruelty and collapsed into despair. Perhaps he would have been filled with guilt over his inability to stop the killings and question the extent to which his country did enough to stop them. Or perhaps he would have been filled with righteous anger and devoted his life to bringing every last Nazi to justice. (It wouldn’t be totally out of character for a Marvel character to become a Nazi hunter, after all.)

Few people would want to see Captain America curled up in a fetal position, crippled by PTSD, or Captain America as a cold-blooded Nazi hunter, but I think many would share my interest in wanting to know how this idealized symbol of righteous American power would have reacted to this most extreme situation. Presumably with great sadness, possibly with some disillusionment as well, but also great compassion for those that suffered, not to mention an even stronger resolve to keep fighting and preventing such evil from happening again.

Captain America as Struggle for Racial Equality?

Gabe Jones, Black Guy

The above Holocaust scenario is pretty far removed from the movie that came out this past weekend, but the subject of race isn’t far from it at all; it’s on screen for anyone to see, although it’s never explicitly discussed in the movie.

As I mentioned earlier, there are two racial minorities in Rogers’s core team: Gabe Jones, an African-American who learned both French and German at Howard, a prestigious black college, and Jim Morita, a Japanese-American from “Fresno,” which he points out to Rogers after he mistakes him for a Bad Guy Japanese. Both would have been the subject of harsh discrimination during the World War II era. African-American soldiers were typically prohibited from combat and mostly relegated to service roles. Segregation of America’s armed forces didn’t end until 1948, and persisted unofficially through the end of the Korean War in 1953. Japanese-Americans were, of course, infamously interred into camps in the United States. Japanese-American men not in the military were given 4C draft status–“enemy alien”–and all those that were in active duty were discharged shortly after the Pearl Harbor attacks. Both African- and Japanese-Americans would eventually create specialized fighting units that served with distinction during the war (the Tuskeegee Airmen and the 442nd Infantry Regiment, respectively), but those were the exceptions, not the rule.

Jim Morita, Asian Guy

All of this would not have been lost on a “kid from Brooklyn” (especially one that paid close attention to the newsreels before movies, as was depicted in the movie). Suspicion of Japanese-Americans was rampant after Pearl Harbor, and the internments made national headlines. Closer to home, New York City’s history before and during the World War II era is pockmarked with numerable moments of significant racial tension, from the draft riots of 1863 to the Harlem Bus Boycotts of 1941.

Jones and Morita were not strangers to Rogers. The movie alludes to a strong sense of camaraderie among the men, and given the awesomeness of their action montage, it seems that they’d been through a lot together. Surely the subject of racial discrimination would have come up among the men, especially with Morita, who, being from California, very likely had family living in internment camps at the time.

My interest in wanting to see how Rogers would have reacted to these conversations goes beyond a simple wish that any given commercial movie be more sensitive to topics of race and prejudice. It’s more directly tied to my desire that Steve Rogers be forced to confront these issues. Not in spite of the fact that he’s Captain America, but precisely because he’s Captain America.

Thomas Jefferson: white guy, slave owner, the original Captain America?

Many have argued–myself included–that the one common thread running through the long, sprawling, complicated American narrative is the tension between the loftiness of its egalitarian ideals and the constant internal struggle to turn those ideals into practice. The same man who wrote “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” into the Declaration of Independence also owned hundreds of slaves on his Virginia plantation. Over 200,000 Union and Confederate soldiers died in a war fought over slavery, a war whose legacy was still unresolved at the time of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s and in many ways remains unresolved today, in the 2010’s.

Oh, and we fought a war against a genocidal racist maniac while our own army was racially segregated.

In other words, the struggle for racial equality isn’t the seedy underbelly of American identity. It practically defines it. And this is why I see the lack of any acknowledgement of racial tension in the Captain America movie as a real lost opportunity. As our idealized symbol of righteous American power, Captain America should obviously embody all of the great things about the American spirit, but he shouldn’t pretend that the terrible things about the American spirit don’t exist or ignore their destructive power. In fact, if he’s the Great American Hero we so desperately want him to be, then he should be confronting these issues head on.

Asking for a Captain America movie in which our hero saves the Jews is probably too much to ask for. So would a Captain America movie in which Rogers leads a Civil Rights movement at the same time he’s battling Nazis/HYDRA in Europe. But I don’t think it’s too much to ask for a Captain America movie in which Rogers has to confront American racism, at least a tiny little bit, among his close-knit, multi-cultural squad.

But It’s Just a Summer Action Movie

Those that say I am in fact asking too much of this movie, that it shouldn’t really be criticized for skirting the issues of the Holocaust and racial prejudice, wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. Captain America, in spite of its historic setting, is ultimately a fantasy movie, not a gritty realistic portrayal of hardship during World War II. It has no “obligation” to tell a more complicated, thought provoking story. You could even say that X-Men: First Class, with its moral dilemmas and civil rights allegories, more than adequately plays that role for this summer’s slate of superhero movies.

None of these things are necessarily wrong. And I remind you of what I said at the beginning, that the movie “made the safe choice” to not include things like the Holocaust and racial prejudice in its story, and that at least partly because of that, the movie succeeds in providing solid entertainment.

But let me close with this thought: were the signers of the Declaration of Independence (yes, those same slave-holding white guys) making the “safe choice” when they signed their names to a document that essentially marked them as traitors to the British crown? No. America was created by those who made the unsafe choices, those who took risks, those who challenged the status quo.

Shouldn’t Captain America do the same?