[It’s Game of Thrones Week here on Overthinking It, which requires a fiddly spoiler policy. Some of these posts have spoilers through the end of the first season of the HBO show. Some of them are just generalized discussions of the world of the Westeros, safe for any reader. This post in particular has spoilers straight on through to the end of the latest book, which means that Belinkie can’t read it. Nyah, nyah! It also gives away some plot points from the competing epic fantasy franchises The Wheel of Time and The Sword of Truth, so if you’re the kind of person who cares about spoilers, maybe just skip this one. —Ed.]

It is generally thought that National Socialism stands only for brutishness and terror. But this is not true. National Socialism—more broadly, fascism—also stands for an ideal or rather ideals that are persistent today under the other banners: the ideal of life as art, the cult of beauty, the fetishism of courage, the dissolution of alienation in ecstatic feelings of community; the repudiation of the intellect; the family of man (under the parenthood of leaders). These ideals are vivid and moving to many people, and it is dishonest as well as tautological to say that one is affected by Triumph of the Will and Olympia only because they were made by a filmmaker of genius. Riefenstahl’s films are still effective because, among other reasons, their longings are still felt, because their content is a romantic ideal to which many continue to be attached…

—Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism”

Let’s just get this out of the way. I am not calling George R. R. Martin, or any of the other authors discussed in this post, a Nazi. Nor am I calling them Blackshirts, nor connecting them with any other historical group of totalitarian assholes. The aesthetic principles I’m discussing here are neither the result of fascism nor indicative of fascism, they just take advantage of the same emotional circuitry that fascism takes advantage of. These are not politicized aesthetics, rather, fascism is aestheticized politics. It’s not quite accurate to claim that aesthetic similarities don’t imply any ideological similarities at all, but that’s a lot closer to the truth than the other way around.

That said, it cannot be denied that the fascist aesthetics described by Sontag (and read that whole article here if you haven’t, or if you need a refresher) is a big, big part of the epic strain of sci-fi and fantasy.

Triumph of the Will, 1934

Star Wars, 1977

And it’s also an important element of the “Blood, Tits, and Scowling” genre codified by Perich yesterday,

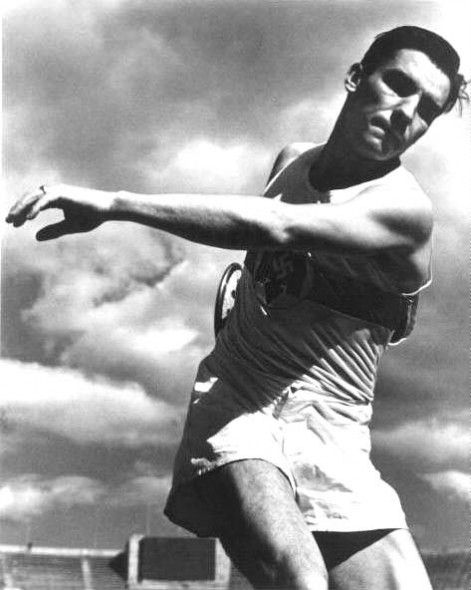

Olympia, 1938

Spartacus: Blood & Sand, 2010

at least in some of its more baroque manifestations. And since the HBO Game of Thrones series is both of these things, it’s certainly worth considering the degree to which it partakes in the fascist aesthetic.

So yeah. The fascist aesthetic. What is that, exactly?

Fascist art depicts, in Sontag’s words, “unlimited aspiration toward the high mystic goal, both beautiful and terrifying.” It “celebrate[s] the rebirth of the body and of community, mediated through the worship of an irresistible leader.” It focuses on “the contrast between the clean and the impure, the incorruptible and the defiled, the physical and the mental, the joyful and the critical.” It fetishizes “the holding in or confining of force; military precision.” Its characteristic subject matter is “vivid encounters of beautiful male bodies and death.” In short, fascist art depicts the perfected, disciplined body in service of the perfected, disciplined state. Its aesthetic principles are, in visual terms, clean geometric lines, chiseled physiques, and slow motion; and in musical terms, brass fanfares, pounding drumbeats, and pipe organs. Its moral principles are strength, skill, obedience, order, joyful submission, and apocalyptic dissolution… and it’s this last that really set it apart from other aesthetics that glorify strength (of which, to be sure, there are plenty to go around).

Fascist storytelling always hinges on a moment of transfiguration, a one-way-only gate through which the agonized hero cannot pass without being transformed into a thing unrecognizable. Crucially, what lies beyond is not something that we get to know. It has to be utterly alien and eternally remote. It was not given to Moses to enter the Land of Caanan, but at least he got to look at it. Fascist art contents itself with less. We see the moment of transition, the event horizon as it were, but we get only the barest glimpse of what lies beyond. The proto-fascist mountain-climbing films described by Sontag arguably fail to capture this aspect, because mountain peaks are reachable. (I mean, we’ve done it, you know? The peak of Everest is pretty well covered with litter.) The ultimate fascist mountaineering narrative, then, would be that of Sisyphus — but a joyful Sisyphus who has chosen his own punishment. Or better still, a thousand joyful Sisyphi.

Fascist storytelling always hinges on a moment of transfiguration, a one-way-only gate through which the agonized hero cannot pass without being transformed into a thing unrecognizable. Crucially, what lies beyond is not something that we get to know. It has to be utterly alien and eternally remote. It was not given to Moses to enter the Land of Caanan, but at least he got to look at it. Fascist art contents itself with less. We see the moment of transition, the event horizon as it were, but we get only the barest glimpse of what lies beyond. The proto-fascist mountain-climbing films described by Sontag arguably fail to capture this aspect, because mountain peaks are reachable. (I mean, we’ve done it, you know? The peak of Everest is pretty well covered with litter.) The ultimate fascist mountaineering narrative, then, would be that of Sisyphus — but a joyful Sisyphus who has chosen his own punishment. Or better still, a thousand joyful Sisyphi.

And so stories of agonized struggle tend to end with ceremonies. The hero becomes the king, ushering in a golden age, but we don’t ever get to see the king, like, paying down the national debt, or building a lot of libraries, or doing whatever else a golden age would really entail. Superhero franchise reboots tend to work this way as well, at least when they end with the moment where Peter Parker affirms once and for all that he is Spiderman. We know more about the day to day business of being Spiderman than we do about the day to day business of running a nation-state (which may explain why our society is in decline), but nevertheless, there’s an important vacuum here. You don’t get to see the day to day life of a superhero because that would be boring, and it wouldn’t solve all the problems of the world. To make the audience believe that the heroic agonized body has ushered in a utopian society, you need to focus solely on the moment of transformation. “I am Spiderman!” he declares, and then we see one more glorious swoop of the CGI-perfected disciplined physique in motion over the New York City skyline — and then credits. In 2001, the moment of apotheosis is the stargate sequence, after which the movie rather pointedly just up and ends. But this kind of creativity is pretty rare. Other than coronations (actual or self-imposed, superheroic), there seems to be a certain limited repertoire of events that work well for this kind of apocalyptic closing gesture: graduations, migrations, weddings, childbirth, sex (especially first sex, or first sex for that couple), and — this being the big one — glorified death.

Tolkien only ever dabbled in this kind of stuff, but it’s part and parcel of modern epic fantasy. The main characters in Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time are “ta’veren” which basically means they are magically empowered with a cult of personality that inspires — among other things — stalkerish devotion from their supporters. All three of them start as farmers and end up leading nation-states. And it’s stated explicitly (and over and over again, I might add) that the two slightly-less-main of these characters have to dedicate themselves to supporting the mainest character of all in his apocalyptic showdown with the forces of darkness, in which he will (probably) sacrifice his own life. They get to be heroes and kings pretty much as a side effect. It ends up being a story of glorification through sacrifice and submission, which is probably the core of the fascist aesthetic. An even better example is Terry Goodkind’s eminently readable but frankly appalling Sword of Truth series, which is all loyalty oaths and sadomasochism, and dodgy conflation of loyalty oaths and sadomasochism… In the first book, the hero and heroine can never be, uh, intimate, because if they did he would be blasted and brainwashed by the magical puissance of her hoo-hah, becoming so devoted to her that his old personality would — hey, don’t look at me, people, this was an international bestseller. At the end, it’s revealed that because the hero is already so completely in love with the heroine, her magic has no effect on him. Again: through submission, glorification. Love conquers all, I guess, but sometimes love ends up conquering Poland. (And yes, this hero too starts as a hayseed and ends up as literal king of the world.)

And then there’s Martin. Game of Thrones starts out as anti-fascist in aesthetic. There seems to be no such thing as a triumphant apotheosis, at least not in the first couple of books. It’s not that the mountain peak can’t be reached: it’s that the whole mountain was a delusion, and those who try to climb it are in for a nasty surprise when gravity kicks in. Trial by combat fits into the aesthetic of fascism beautifully — justice carried out through perfected, muscular bodies engaged in a glorious mortal struggle — but it only fits if the trial by combat is glorious, and only if justice is actually served. There are two trials by combat in the books. In the first, Martin makes a big point of showing how the fight is not glorious. The second trial is a bit more poetic — but the wrong guy dies, and an innocent man is convicted. Neither of these glorifies the state, or the body, or the attitude of submission. Or take that scene from the season finale, where Robb’s supporters are bellowing “THE KING IN THE NORTH!” That would certainly seem like aestheticized fascism. But it takes the bloom off the rose when you remember that [and I think a secondary spoiler alert is justified here] most of the people in that room, Robb included, are going to get put to the sword by Roose Bolton and Walder Frey. A shorter version of that whole cycle plays out within the first book alone, with Dany’s unborn son. He was to be named “Rhaego, the stallion who mounts the world,” something which I read as “rides the world” when I read it back in 1996, and have now decoded more accurately as “f___s the world.” The scattered Dothraki tribes would finally unite under his overwhelming strength, and then, exalted by their submission, they would cross the narrow sea and stampede throughout Westeros, slaughtering and raping as they went. Under a value system that glorifies strength, this would count as a happy ending. But the apotheosis is not to be: the stallion who mounts the world gets taken out by a vengeful midwife before he’s even born.

Even that, though, is tragic, and tragedy always has the potential to shade into a glorification of sacrifice. The real challenge to fascist aesthetics comes from the series’ unperfected bodies. Some bodily abnormalities can be reconciled with fascist narratives — Jaime pretty clearly loses his hand just so that he can, through agonized struggle, climb the mountain, touch the peak, and reclaim his status as a perfected instrument of death. Brienne’s harped-on ugliness is there so that we can focus on her bodily perfection in terms of skill and strength. Varys’ castration is tied in with his utter dedication to serving the realm — the fascist body needs to be disciplined and perfect, but in all three of these cases bodily imperfections are just opportunities for more and further discipline. But the same can’t be said of Tyrion. He is quite precisely undisciplined. He drinks to excess. He likes his food. He has sex — he doesn’t make love, he has sex, and often, and never in idealized terms. He pisses. I don’t remember whether he shits or not, but others shit in his presence. He cracks jokes. He loses his temper and alienates his friends. All of this brings in the spirit of the carnival and the grotesque, which is the mortal enemy of fascist self-seriousness. Much the same can be said of Samwell Tarly, with his gross fatness, his cowardice, and his incontinent lusts. Robert Baratheon’s drunkenness, Doran Martell’s gout… This was the major initial attraction of the series, I think, to many, or at least to me. It peeled off the gleaming facade of the fantasy novel to reveal a foundation crawling with termites. And, critically, it found something beautiful in it. The story is grim and violent. Often, we are dismayed when we see people who should be good being bad: a knight of the kingsguard punches Sansa in the stomach, Littlefinger turns on the Starks, or Joffrey, like, breathes or walks into a room, that asshole. But with characters like Tyrion and Samwell, the story celebrates human weakness rather than despising it. And that is the one thing that fascist art will never countenance.

However. As the books go on, the fascist aesthetic begins creeping back in. There are three main places where I see this happening.

1) The kingsguard.

The Kingsguard is an elite military unit dedicated to, uh, guarding the king. It’s made up of the seven greatest knights in the realm (so quite literally the seven most perfected and disciplined bodies), and they are fanatically devoted to the head of state. They’re also celibate, adding the little whiff of sexualized restraint that any good fascist art needs. And theoretically, at least, they are also spiritually perfect. Because, you know, skill in combat and spiritual purity go hand in hand. In the early books, much is made of how glorious the kingsguard looks, in their spotless white cloaks, but they are exposed as a bunch of brutish louts, save for Ser Barristan, who is noble but well past his prime. So at the beginning of the story, the Kingsguard is about exposing the fascist glorification of force as hollow. But over the course of the books, this begins to shift. When Jaime Lannister becomes the leader of the kingsguard, it pretty clearly saves his soul. And one of the ways that we know this is that he starts taking the celibacy oath seriously. Ser Barristan, who already had the spiritual purity thing down, gets a physical competence upgrade — turns out that even as old as he is, he’s probably one of the world’s greatest swordsmen. And unlike his lesser brethren, who are still serving the series’ designated bad guys, Barristan jumps ship and goes off to worship the real irresistable leader, Danaerys Targaryen (for which see below).

2) The Wall and the Watch.

Like the Kingsguard, the Watch is a military order. And like the Kingsguard, they are sexless. (Institutional male celibacy seems to be kind of a thing for Martin.) Unlike the Kingsguard, they aren’t elite. In fact we’re told quite explicitly that you go into the wall as the scum of the earth. But the order transforms them. Their submission makes them into a swords, disciplined and perfected. The brothers of the watch still have their failings and foibles, and the worst of them — deserters and murderous traitors — are as bad as anyone, anywhere. But the redemption narrative is played straight often enough. And then there’s the Wall, and the North beyond which it metonymically represents. Sontag again: “As usual, the mountain is represented as both supremely beautiful and dangerous, that majestic force which invites the ultimate affirmation of and escape from the self—into the brotherhood of courage and into death.” And a key element of the continuing plot involves Bran traveling north, beyond the Wall, to achieve some kind of mystical apotheosis in the frozen lands beyond. The threat of the White Walkers is also interesting here. There’s always been a sense that the political and military struggles that make up the bulk of the books are ultimately meaningless, because, well, zombies, right? It doesn’t matter who’s sitting on the Iron Throne when the dead are walking in the night. And that means that everyone is eventually going to need to put aside their struggles, strap their armor on, and march north. Which means that the apocalyptic vision of the Night’s Watch — setting aside all material concerns in favor of a titanic military struggle against a literally inhuman foe, and more importantly, being redeemed and perfected by that struggle — turns out to be the right vision. It’s submission to an ideal rather than submission to a glorious leader, so it’s not quite fascist as Sontag describes it. But it’s in the ballpark. And speaking of glorious leaders…

3) Danearys Targaryen.

Dany’s story in the first book is great. The way she gets gamed by Mirri Maaz Durr is heartbreaking. Mirri’s reasons for doing it are heartbreaking. At the end of that book, Dany seems like the series’ most intensely vulnerable character — we’re not worried that she’ll get killed, necessarily, since she’s obviously so important — but there’s a real concern that she’s going down the wrong road, becoming a monster.

As the series goes on, however, Dany becomes more and more of a Mary Sue, which, considering that she starts out as the violet-eyed last scion of a dying house, is really quite an achievement. She attracts a fanatically devoted army of followers. Every man she meets falls in love with her. She becomes absurdly virtuous. Abolishing slavery is a good thing, don’t get me wrong, but she seems to be literally the only person in the world who objects to it — it seems to be used as a crude way to establish that she’s the Good Ruler. And the way that she gets it done is a little off-putting. She approaches the problem with a burning moral certitude, and backs it up with overwhelming physical force. End of story. There do not seem to be any negative (or even any complicated) consequences. And then there are these ancient prophecies popping up, about how she’s going to unite and save the world… the story begins to hit some very familiar beats. The collapse of the prophecy about Rhaego made it seem like this was a series where all myths are false. There is no preordained savior, no mystical leader: people just muddle through the best they can, and make up stories afterwards. But it’s looking more and more like the endgame of the books is going to be a struggle between Danaerys’ true myth, and everybody else’s false myths. And that arguably makes it worse. The charm of the series was that it deflated the fascist fantasy, demanded that we accept normal, fallible humanity as a story worth telling, even in a fantastical realm. But what if Martin doensn’t think it’s worth telling after all? What if all of the first four books were just an extended tour of the Weimar republic? What if the seven kingdoms, the Starks, the Lannisters, all of it, is just so much rubble to be cleared away by the cleansing fire of Dany’s ascension? What if Game of Thrones was never really a departure from the fascist aesthetic after all: what if Westeros was just waiting for the right führer to come along?

Stokes, I think you missed another big fascist signifier in Dany’s story [and this is a spoiler]: In A Storm of Swords she acquires a huge army of highly trained elite warrior eunuchs, the Unsullied. They are trained since birth, they are literally nameless, they are highly disciplined, and they have all sexual and emotional feelings removed from them. The name alone suggests a unit of the Third Reich.

All that said, while I do follow your arguments, I have to trust that Martin won’t be taking the easy way out in his series, and that it won’t devolve into Dany as an idealized Hitler. The books have shown too much sophistication and narrative complexity to this point, and too much interest in undercutting the standard tropes, that I can’t believe he would retreat back to such cliches at this point.

I agree it’s a bit early to be prejudging the resolution of Dany’s story – nothing else that’s happened in the books has so far turned out exactly as the reader or the protagonists have expected.

Mance Ryder, Khal Drogo, King Joffrey, Robb Stark and Renly Baratheon can all tell you about the vagaries of fate…

Y’all do have a point. But let me reflect this back onto the Robert Jordan books again. In The Wheel of Time, the main character, Rand, is “the Dragon Reborn,” a reincarnation of a fantastically powerful wizard who lived thousands of years ago, who is prophesied to come again at the end of days, conquer the world, and lead the united forces of humanity in an epic struggle against Satan. This prophecy is unambiguously true; it’s what the whole series of books is about.

Now, one of the author’s more interesting conceits is that Rand is far from the first guy to show up claiming to be the Dragon Reborn. There have been dozens of “false Dragons,” over the years, who have tried to conquer the world, failed, and been executed or deposed. At one point, Rand has a confrontation with one of these guys, who gives Rand the ol’ “we’re not so different, you and I” speech. Rand says “The difference is that I really AM the Dragon,” and trots out a bunch of prophetic signs that point to this being the case. The false Dragon smirks at him, and basically says “yeah, well, if a couple of more things had gone right for me — if I had won this battle, not led my army across that river, etc. — then I would be ruling the world, and I would really be the Dragon. And people would find a way to make the prophecies fit, just like they’re doing with you.”

The interesting thing about this is that, in the world of the books, the false Dragon is provably, unambiguously, WRONG. We’re not supposed to question whether Rand is actually the messiah: if anything, we’re supposed to learn that the false Dragon cynical and deluded — what TV Tropes calls a “Flat Earth Atheist.”

In Game of Thrones, there’s also a messianic prophecy, which claims that “when the red star bleeds and the darkness gathers, Azor Ahai shall be born again amidst smoke and salt to wake dragons out of stone.” Most readers assume that this refers to Dany, who has managed to hatch her stone dragon eggs (and whose birth also fits, for slightly more complicated reasons). In-universe, some people are claiming that it’s Stannis Baratheon — but this does not seem remotely plausible to me, and I don’t think Martin even wants us to see it as plausible. Stannis is currently trying to decide whether or not he should murder a bunch of children in a magical ritual to make a dragon statue come to life, so that he can fulfill the prophecy. So messianic candidate number one ends slavery, messianic candidate number two murders children. Decisions, decisions! Granted, Martin has surprised me before, on multiple occasions. But if it does turn out that Stannis really is the chosen one, or that the prophecy is bunk after all and Dany is nothing special… well. Surprised wouldn’t begin to cover it.

The fact that false messiahs have come to grief does not necessarily mean that the narrative will not have a true messiah. There can only be one, right? If Colonel Mustard, Ms. Scarlet, Professor Plum, and Mrs. Peacock are all innocent, it does not necessarily follow that Mr. Green is NOT guilty.

I’m not sure you’re anticipating the correct subversion of the trope. From what I’ve inferred of Martin’s philosophy from reading these books, it doesn’t seem likely that it will ultimately *matter* whether or not Dany is the “messiah” in this prophecy. I find it much more likely that Dany will actually be that fulfillment… but that that won’t be the end, or the “point” so to speak.

Time and time again, Martin proceeds from the notion that what is crucial is ultimately inconsequential. The series, as a whole, is entitled “A Song of Ice and Fire.” Now, Dany is clearly the “fire,” and the prophecy encourages that, and I believe it will be fulfilled and play out that way. What ISN’T clear is how the “ice” plays into it. The “white walkers” SEEM to originate from the north… but there are two HUGE problems with framing Dany as the “good Hitler” who will take a happy successful army of Fire against the evil Ice-y zombies to fulfill the fascist aesthetic.

First, {SPOILER} those aren’t the only zombies. Dondarrion does a perfectly good job of zombifying Catelyn without being from beyond the Wall. IF zombies are the ultimate evil of the series (which I strongly doubt), then they don’t strictly fit into the “ice vs fire” paradigm, which is the only framework which allows for Dany to emerge as Victorious Leader.

Second, “beyond the Wall” has proven to be a highly varied and complex place. There is possibility for a rising power there that is entirely independent of zombies, and that could stand against zombies either in conjunction with a triumphant Dany, or on its own, and could indeed be a “heroic” force standing against a negatively-framed fascist-Dany.

Wonderful essay. Perhaps some of what has delayed Martin’s completion of this series (and caused him to extend and extend it along so many tangents) is his reluctance to–pardon the pun–submit to the apotheosis trap he has set for himself. Here’s hoping he navigates the gray areas (cool and warm?) between Ice and Fire.

I was wondering about this comment: “Jaime pretty clearly loses his hand just so that he can, through agonized struggle, climb the mountain, touch the peak, and reclaim his status as a perfected instrument of death”

That’s not really how I’ve read it so far – he certainly undergoes agonised struggle, but so far he hasn’t really seemed likely to reclaim his fighting abilities. It’s clearly a redemption story, but it seems more that he’s learning humility rather than – cue montage – becoming even more bad-ass.

Strong second to this comment. Jamie has, thus far, managed to just about hold his own against Illyn Payne, who sucks. Sure, in any other fantasy novel Jamie would overcome his hardship and achieve levels of badassitude with his left hand that he never dreamed of with his right, but in GoT he’ll probably keep sucking, or die out of hand.

I for one would love to see a badass montage of a character learning humility set to the strains of Loverboy’s “Working for the Weekend.”

That said, while I’m not totally sure Jaime is going to succeed in becoming a bad-ass again, I don’t think “humility” is the right word either. He’s becoming a “true knight,” in the series’ parlance, which judging from the examples we’ve encountered means being brave and honorable, but also implacable and a bit of a prig. And it does also imply impressive murdering skills. (The series’ one candidate for a physically incompetent “good knight,” Ser Dontos, turned out to be in it for the money.) In any case, whether he’s going to succeed in becoming a badass or not, he’s tirelessly working to achieve that end. The radical departure would be for him to accept the things he cannot change (AA style), stop practicing swordplay, and take up

needlepointtennissome self-consciously non-macho hobby that’s easy to do with just your off hand. I don’t see that as being in the cards.I agree, ‘humility’ is not the right word – I can’t see him becoming a monk. Rather, he’s learning that being good at killing need not define him. As you say, that does seem to be a pretty important part of most characters’ job descriptions, so this rejection of narrowly-defined ‘power’ in favour of ‘soft power’ – see his negotiation with Edmure Tully – works counter to a fascistic aesthetic.

He is still trying to become bad-ass, of course – it would be very out-of-character for him to simply give up – but I’d be very disappointed in GRRM if he ends up simply being a mighty monohanded massacre machine.

@ Andy: “or die out of hand”

Oh, I see what you did there, ser.

First, great article.

One thing that I think should be mentioned, and it’s something that makes me hope that Martin will stay in the complicated grey areas, is what happens in the last parts of Danaerys’ story . [Here comes another spoiler]

After she takes the third city — Mereen, I think — she finds out that the “council” she set up in the first city has been replaced by a tyrant. She decides to stop her victorious march west and go back and learn how to rule. To be sure, this could still be just a step on her mythical ascension to ultimate leadership, but it does set up the possibility that the story is going to deal, at least temporarily, with what comes after the coronation.

Of course, maybe Martin will just skip the whole thing and take up the story again after she’s become an amazing leader and she’s resumed her conquest of the world.

That is a good point — I’d forgotten. And the odds that Martin will actually talk about the process of governance are not so bad. We got to hear about Tyrion’s tax increase, after all! (Probably a first for epic fantasy, that.)

Of course, since this is ASOIAF, it was a tax on whoring.

The tax on whoring was Tywin’s idea

Also, how will she deal with her dragons eating little children?

I think the jump to only acknowledging these techniques as specifically and exclusively fascist is pretty forced to fit the article pitch. You basically end up with an argument (that’s worth having, as they always are) to not always immediately condemn fascism as innately bad. The things you bring up have been used in stories since humans starting telling them, for many reasons and in many ways. Just a bit simplistic to go, yeah Saving Private Ryan is fascist because they achieve glory for the state by submitting, movie summed up, what’s next?

A great post! Thank you.

As Sontag notes, the particular tropes she sees in Riefenstahl are “fascist” in her case, because of Riefenstahl’s personal political history.

As Sontag says, many of these tropes were used in official Communist art, also. And some of them were developments of pre-existing European art tropes, such as the pure male brotherhood under a superior leader: cf. Sarastro’s Holy Brotherhood in the Magic Flute. And that was itself just a twist on the various religious or secular brotherhoods which dotted European history.

So we need to be able to discuss “fascist” art while feeling little sting from the word itself. The complex of attitudes can be found quite broadly, even if especially among various totalitarian movements. I myself feel little political pull from watching or reading “Game of Thrones”, and I don’t favour replacing Obama with Kal Drogo. It’s fantasy.

Interesting, but I feel that the the themes of the ‘fascist aesthetic’ are far to broadly human to be applied with the sort of scatter gun precision that the article ascribes to. The idealized fascist image of the hero is and was only a pruning of a larger more complete tree that ascribed to human perfection. We are nothing if not communal beings and much of the fantastic virtues that we ascribe to our hero involve the ideal integration of the self with the tribe through semi divine leadership through love and power. The perfection of the self (via martial, mental and physical prowess) leading to societal love and acceptance are themes that are as old as fiction. Gilgamesh, Siegfried, Arthur.

To accuse a work of fascist themes seems to me to demand a higher standard of proof than simple shoehorning. The argument for the wheel of time for example is a solid one as it embraces many of the most obvious bullet points but in the Song of Ice and Fire so much of the author’s time is spent on the kneecapping of fascist points that when he eventually does get around to a more standardized hero’s journey it is hardly a ringing endorsement of the tropes.

Even in the organizations that the article cites as fascist one of the most important points that GRRM hammers home time and again is that the ideal of the organization hardly fits the reality. Time and again we are notified through history and rumor as well as the occasional PoV that the kingsguard of the past was manipulative, lecherous and vain. That the “true knights” were often the exception not the rule. Likewise the nights watch holds to it’s celibacy so loosely that it is a public secret that it is in name only. Every single character who has been shown has violated their vows and been shown to be doing if not the right thing than at least the kind or human thing. Whats more a full half of the brothers prove to be no better than bandits when the iron hits the anvil and instead of being transformed the loyal remainder die piecemeal as they struggle to return to the safety of the wall. The day is saved by cripples and boys not because they feel a glorious duty but because they are desperate not to die.

On more specific character notes the idea of Jaime as a fascist ideal is patently ridiculous. His maiming is treated as a whole sale lessening. The crippling of a great and glorious beast. The only improvement that it gives is that it destroys utterly the man that he is and forces him to reevaluate who he can now be. In his own words it forces him to ask the question “how is it that the boy who wished to become (a knight in shining armor) became a (psychotic thug).” Furthermore what saves Jaime’s soul is not his appointment as lord commander but in fact the ugly woman who reminds him that ideals can be upheld. A person whose views are truthfully a delusional fantasy that end with her being unjustly hanged by her own former mistress over a misunderstanding that her true honor created.

Dany is the only person that a decent argument can be constructed around and yet even here the argument has it’s fair share of rotten supports. Let it first be said that Dany is a Mary Sue only by gross reduction and comparison. Drop her next to Rand Al’Thor and you could barely see her sue-light next to the incandescent sun of the Dragon reborn. Rand is literally so strong of a god head that he can take a city from rioting starving chaos to order and satiation with twenty words to the right three people. Dany finds out first hand that she doesn’t have this power when the Khalassar of her husband abandons her. Her actual power is not inherent but is instead via the loyalty of three dragons. Creatures that represent the apotheosis of force. Creatures whose nature is turning out to be rather less lovely than initially thought. What with the devouring of children and all.

Furthermore the freeing of slaves is not treated as a consequence-less act of moral superiority. Many die of starvation and disease, the cities she “frees” become in order a brutal dictatorship where the former slaves lord over their former masters, butchering them in the streets and mutilating them to create more unsullied, unchanged and finally a seething hotbed of resentment and insurgents that Dany attempts to rule over once she realizes that she is no better than her pillaging husband. But only after she crucifies 163 men and women of it’s aristocracy in a righteous rage.

Dany is the closest thing to a mythic protagonist but that is only because stories that devolve into a muddle of failure only work when they are written by Cormack McCarthy and even then only once. Any character in this series that seems to be the least bit effective in fixing the problems of the world will by the very contrasting nature of their success open themselves to the accusation of fascism. It’s just the way the cookie crumbles. Dany might seem like she is the real deal. The true myth but much of what makes her compelling is that after so many pretenders to the throne of “protagonist” (AKA fuhrer, apparently) she is emerging as a real contender. These devices exist because they are fundamentally satisfying to the human psyche and their use doesn’t denote any ideology beyond a desire to tell a fulfilling story.

Still, as the books themselves so wonderfully put it, when it comes to myth and prophecy, “prophecy will bit your prick off every time.”

Great response SodiumAzide (0.1M keeps my reagents nice and clean without killing my lymphocytes). The culmination of events into an end of history is an extremely common trope, and acts as both a denoument and a logistical inevitability to story length, so it’s hardly fair to label it to specific genres and ideologies.

I still wouldn’t agree with you regarding Dany, as the OP said, she behaves far too much like a modern liberal than a feudal aristocrat (no matter her life experience). I’d also be more critical of Jon Snow, it was obvious he was Lyanna’s son from even the first book, I can’t quite explain it but he feels far too perfect and boring compared to the rest of the cast.

Nevertheless, I have no delusions that Dany and Jon will do a tag-team rampage across Westeros, defeating the ice demons and reclaiming their birthrights and ushering a new, less inbred Targ royal family. The series is far too savvy for that.

Holy crap, I just realised, Jon Snow is an idealised Harry Potter.

First, great article. Second, it seems so utterly wrong. As some readers have noticed it stretches the definition of fascist too much. In this manner almost everything, most of the cultural tropes and organizations in western culture and history can be labeled fascist: starting from communist, socialist realistic art with those steely eyed, angular and heroic worker-soldiers, utterly devoted to five years plans and destruction of fascism. Then we have Christian knightly orders on which Kingsguard and Night’s Watch are partly modeled, certain country where abolition of slavery required bloody civil war, almost every book and movie hero striving to self-improvement. Of course it may be so because fascism has taken so much from history and culture, used those things that worked well in arousing feelings. But if it is so, is it justified to call them fascist?

An interesting prospect and I do definitely see the last point in particular as the central idea; especially in the last scene of season 1. I never read the books, but the way I’ve been mulling it over makes me think that their world, their system is so fanatically stupid, corrupt and impractical that its only logical course is to be destroyed. It just happens that it will be destroyed by a girl with an army and some dragons. The only things certain is this world are death and revenge. Bureaucracy, the state, order, honor and law are all delusions. This is certifiably proven when Ned loses his head at the end of season 1. (See the Game of Thrones and Noir article from last week.) The only things that really works is warfare and if their whole world burns because they’re all dicks, so be it.

I’m not sure how much a mary sue Dany is, she has a little bit of it only because her arc wasn’t as massive as nuanced as some of the others. Then again all characterization in this show looks bland to me compared to Treme.

Let’s look at the father of fascist story arcs; Richard Wagner. Granted Wagner’s operas were way before the Weimar Republic’s fall, but still its worth looking. Books and books have been written about Wagner; so I’ll tyr to be brief about the compser, the essayist, the patriot and particularly Wagner the racist. In Wagner’s Ring Cycle the whole world comes crashing down at the end after celebrating Nordic mythos for 16 hours. After all the fighting, acts of bravery for love, dragon fighting, talks with gods and all that other stuff that occurs in Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold,) Die Walküre (The Valkyrie,) Siegfried and Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) the whole system falls apart because men and gods alike cannot succeed for all their planning or their strengths. Even Siegfried, who was supposed to be this great brave hero, gets tricked and dies. The only way any of these characters transcend their faults in the end is through death.

Wagner realized that even in a fantasy the system collapses because even though the fascist (or proto fascist) aesthetic reveals in everything Wagner goes through; contrasts of great and small, grotesque and beautiful, brave and cowardly, one thing that brings the whole idea together is apocalyptic transformation. The world has to end in order to made into something better. Perhaps the entire aesthetic is paradoxical, it reveals in a life that eventually collapses due to its own mechanisms. Perhaps these dreams of fascist aesthetic are all for naught.

what a bunch of red assholes! its a goddamn book!

Hi, caralis, welcome to your first time at Overthinking It, which “subjects the popular culture to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn’t deserve”.

I think the commenter who called attention to the scene where we discover that Drogon has eaten a child raises an important point. Viewed symbolically this is a perfect example of how Martin refuses to gloss over the barbarities of authority and war in favor of a simplistic hero narrative. Dany’s dragons symbolize the pure physical power needed to rule; thus with this scene, Martin is saying as bluntly as possible “power eats children.” He is stubbornly refusing to pretend that Dany’s ascension will magically fix all wrongs in the world. And as far as “no consequences” for freeing the slaves–well, I realize this article was written before the fifth book came out, but it’s worth noting that Dance With Dragons completely negates this point; the entire portion of the book which centers around Danaerys is about her dealing with the consequences and discovering that just because you swoop in with an army and some dragons doesn’t necessarily mean you’re ushering in a new golden age.

Also one minor note: whoever said Jon is Lyanna’s son–pretty sure that’s wrong. Ned Stark says in the very first book that his baby momma was a serving girl named Wylla. We hear a bit more about her in the fifth book as well.

In fact, a huge portion of the books have dealt with the day-to-day operations of rulership which you note are lacking in the other “fascist” narratives that you’ve cited. Someone mentioned Tyrion’s escapades as the Hand of the King; I would also note Jon Snow’s struggles to control the Wall and pretty much all of Danaerys’s actions in the fifth book. The point Martin consistently hammers home is that the exercise of power is messy and bloody and almost always creates more problems than it solves.

Also, in response to the commenters discussing the “Fire vs. Ice” narrative–to me it seems like the Ice part includes not just the Others but also all the old powers of the North. Melisandre pretty clearly identifies the weirwoods, skinchangers, and children of the forest as enemies of R’hlorr, and there’s a scene in the fifth book where she glimpses Bran and the greenseer who’s teaching him in her fire and calls them “servants of the Dark One”. True, Melisandre is somewhat deluded but her god seems to have backed her up pretty well so far, and his jealousy does not seem feigned.

The Starks seem to represent the ancient powers of the North–the old gods, the First Men, the children of the forest, the greenseers, the wargs, etc. etc. Meanwhile Danaerys is the fiery conqueror from overseas, harkening back to both the old Targaryens and the Andals who took the kingdoms of the First Men and cut down the weirwoods. I think some type of struggle or at the very least tension is likely brewing between the old dark North and the bright young South. This alone will probably interfere with any kind of simplistic “Danaerys flies in on her dragon and saves the day” ending.

Oops, that thing about Wylla was supposed to go at the end.

As a fascist, I quite enjoyed this (and ASOIAF too)

Is this plagiarism? https://medium.com/@joe.streckert/game-of-thrones-fascism-and-false-equivalence-b726a5fba09f?source=friends_link&sk=7aa24a2a03d241bb6ce82415fe4e332e