In each of the X-Men movies so far, the scale of the conflict has been a product of its time.

In the first movie (X-Men, 2000), the danger is terrorism: a radical ideologue threatening a gathering of world leaders with a radiological weapon. It’s interesting to examine X-Men’s sympathetic treatment of terrorism, and its skepticism about the growth of government powers, in light of the War on Terror (fodder for a future post, if anyone wants to submit an article). In the second movie (X2, 2003), the conflict is now over racial identity. Does being a mutant automatically require conflict with established institutions, or can mutants and humans live in peace? By the third movie (X-Men: The Last Stand, 2006), the conflict turns into outright war. Magneto gathers an army of mutants to attack a pharmaceutical company, and the confrontation is public and explosive.

So where does that leave X-Men: First Class?

First Class is set in 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It is the height of the Cold War, with tensions between the West and the Soviet bloc as hot as they could get without reaching outright bloodshed. The U.S. places ICBMs in Turkey, close enough to destroy Moscow. In return, the U.S.S.R. dispatches ships loaded with ICBMs to Cuba, which will put most of the Eastern seaboard in peril.

(SUBSTANTIAL SPOILERS for First Class follow)

Despite the explosive mutant battle on the shores of Cuba that caps the film, the primary conflict in First Class is espionage. Sebastian Shaw operates behind the scenes to provoke the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. to the brink of nuclear conflict. He’s an ex-Nazi scientist, but he’s so useful to the Eastern and Western powers that they still take meetings with him. To combat him, Charles Xavier and Erik Lensherr team up with the CIA. They recruit a team of special agents from the private sector and turn them into paramilitary operatives.

First Class is a story of the Cold War. While there are established (if not always honored) rules of warfare, a cold war – a war of spies and diplomats – has fewer explicit codes. The question of methods is foremost. Is blackmail acceptable? What about torture? Assassination? If you use immoral means to achieve a moral end, does that leave you on the side of the angels? And if you use moral means but fail to achieve your end, was it worth it to even try?

A Wilderness of Mirrors

While First Class is notionally about Charles Xavier’s first class at the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters, the teenagers get very little screen time. The movie and the audience are clearly more interested in Xavier and Lensherr. The world’s most powerful mutants, they represent the divergent goals and methods of the mutant rights movement.

When we first meet Erik Lensherr as an adult, he is alone in a hotel room in Switzerland. He glares at a wall covered with pictures of his targets: Sebastian Shaw, Shaw’s contacts, and the bankers who support him. Lensherr visits one of these bankers, interrogating him on Shaw’s whereabouts. He tortures the banker for information by prying out one of his metal fillings and gets a lead: Argentina. On the way out, he reminds the banker that, should anyone else learn about Lensherr’s quest, Lensherr will be back to kill him.

In Argentina, Lensherr confronts two ex-Nazis, former cohorts of Shaw’s. These men, presumably former soldiers, are more competent threats than a hapless Swiss banker. But Lensherr goes in alone anyway. He teases the men for a bit, goading them into attacking him first. Then he pins one to the table with a knife, compels the bartender into shooting the other one with his magnetic powers, and gets another lead before finishing his work.

What do these incidents tell us about Lensherr? He’s cold-blooded. He has no qualms against torturing or killing in order to complete his mission. In fact, he even seems to like it. Lensherr yanks the filling out of the banker’s mouth after being told of Shaw’s location. And he lets the Nazis in Argentina know that he’s an Auschwitz survivor by showing off his forearm tattoo.

We also know that he operates alone. This might not strike most folks as odd. As a moviegoing audience, we’re used to our heroes being bold men of will who operate without allies. But it’s hardly a requirement, and it’s especially odd in historical context. There was no shortage of well-heeled Jewish survivors in 1962 looking to bring Nazis to justice (q.v. the Mossad operation to capture Adolf Eichmann, for instance). Lensherr could have tagged along with any of those. For all we know, maybe he did off-camera. But the movie depicts him as a lone wolf. He acquires his intel solo and operates solo.

When we first meet Charles Xavier as an adult, he’s picking up a co-ed in a bar in Oxford. As the world’s most powerful telepath, he could use his powers to bed her in minutes. But he limits his mind-reading to determining her favorite drink. Instead, he spins a charming line about heterochromia and mutations. He ends his spiel with a toast – “Mutant and Proud” – that clearly has the girl intrigued.

Of course, Xavier didn’t come to Oxford alone: he brought his adopted sister, Raven, with him. Raven also wants broader acceptance of mutants, even if she’s cynical where Xavier is optimistic. But wherever Xavier goes, Raven goes, too. This extends not just to Oxford but also to Washington, when agent Moira McTaggart recruits Xavier to brief the CIA on the nature of mutants. Raven has no qualifications in genetic science beyond being a mutant, but Xavier wants her along anyway. And she proves useful, too.

Xavier is warm-hearted and affable. He has lots of friends at Oxford, as evidenced by the party thrown for him when he gets his doctorate. He wants to make the world safer for mutants by spreading awareness at a grass-roots level. By getting the “Mutant and Proud” slogan to catch on, he hopes that the rest of society will realize that mind readers and shape changers are not necessarily worse than people with different-colored eyes.

Xavier is also more willing to work with a team. When McTaggart approaches him, he picks up the gravity of her request by peering into her brain. But instead of heading off solo to deal with Shaw and his cohort, he teams up with the CIA instead. This isn’t his only choice. The world’s most powerful telepath probably had as good a chance as anyone of taking down a trio of mutants single-handed. But he wants the resources, manpower and the goodwill that working with a government agency will generate.

Two powerful men. Two different methods. One common goal: making the world a safer place for mutants.

Shaken, Not Stirred

First Class is a story of the Cold War. It’s a story about espionage: secret meetings, influence exerted behind the scenes, states brought to the brink of violence and the fallout of World War II. When people in the Sixties thought about espionage – or when people today think about espionage in the Sixties – they thought of spies. Two spies in particular.

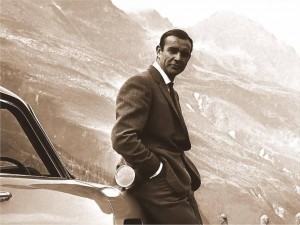

On one hand you had James Bond. The creation of Naval Intelligence officer Ian Fleming, Bond was a Commander in Great Britain’s navy who became an officer in the SIS. Bond has “00-status”, a government sanction to use lethal force in the completion of his assignments. When depicted in novels, Bond doesn’t enjoy killing: he approaches it with the cool detachment of a surgeon. On film, however, Bond is a different character. He often punctuates a kill with a post-mortem one liner (e.g., “I think he got the point”) and can transition from murder to loveplay with little rest in between.

Bond was a spy in search of adventure. He traveled to the most glamorous spots in the world: Jamaica, Istanbul, the Bahamas. He acted alone, faced down overwhelming odds, and emerged triumphant and unruffled. Though he was an agent of a massive bureaucracy, he only checked in with them at the beginning and end of his assignments. And not even at the end, if he had a pretty girl to seduce in the meantime.

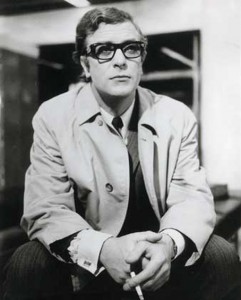

On the other hand you had Harry Palmer. Harry Palmer was first introduced in the Len Deighton novel The IPCRESS File in 1962, just after the first Bond film, Dr. No, was released. Palmer is a former Army Intelligence officer transferred to an unnamed intelligence department. He works closely with other officers in his department. He harangues his superiors for reimbursements that are owed to him and raises in pay. He lives in a small flat. He has a rather modest education, which he supplements by reading up on military history.

Harry Palmer was such an unglamorous personality that, in the Deighton novels, he was never even named. It took the 1965 film adaptation of The IPCRESS File, starring Michael Caine, to give Deighton’s protagonist a name and an accent. Caine portrayed Palmer as snippy with superiors but congenial with his peers. He was hindered by bureaucracy, particularly the squabbles between departments. He wasn’t a martial arts master or a crack shot, but he was clever. In the end, that was all he needed.

(Ironically, the Bond films and the Palmer films were both produced by Harry Saltzmann and scored by John Barry. Now that’s horizontal integration!)

Two powerful men. Two different methods. One common goal: peace in the West and the security of the British Empire.

Good article, but now I want to read spy novels!

Do it! Read them! Very rewarding.

Excellent review! And thanks for the link. I think you’re dead-on about the movie presenting the two types of Sixties spies and exploring that dichotemy, but I would equate Xavier to Smiley much more than Palmer. As you point out, his breeding has more in common with Le Carre’s character, for one thing. Not that Smiley grew up in that kind of wealth, but he later married into it. And he did go to Oxford, and I can totally picture him participating in that same sort of drinking celebration back in the days when he was recruited by Jebadee. Furthermore, he’s a social operator. As you point out, Xavier plays well with others and builds a team. Smiley always uses a team (Connie, Mendel, Guilliam, etc.), whereas Palmer would much prefer to work alone like James Bond. [Minor spoilers follow:] It’s true that the film doesn’t leave Xavier as emotionally wrecked as Smiley, but I’d say that the physical toll he pays is roughly equivalent.

Anyway, none of that alters any of your key points. Thank you for the fantastic analysis!

Excellent point! Although don’t forget Palmer had his team, too. Although I think the Smiley comparison holds as well. Smiley’s only “powers,” if you will, were his penetrating insight – his mutant mind – and the people with whom he surrounded himself.

This is an interesting take, Perich, and it reminded me that Vaughn – unlike Singer or Rattner, both American – is British, a fact which lends credence to your interpretation (and maybe also serves to explain some of the movie’s unfortunate racial missteps, as noted elsewhere.

In fact, it’s likely that Daniel Craig’s breakout gangster role in Vauhgn’s Layer Cake was what go him the role of Bond in the first place.

Racial missteps because he’s British? I would be interested to know why you think that, being British myself…

An interesting comparison I heard from a friend after seeing the movie was that Xavier is to MLK Jr. as Magneto is to Malcolm X. Anyone want to discuss?

That was brought up in the OTI podcast about the movie, actually. I thought of it, too! :)

That’s a pretty established comparison of their ideologies.

Great parallelism between the First Class protagonists and the fictional British spies!

An interesting thing to note about the movie, though: At the end of the movie, Raven/Mystique first chose to side with Xavier, but then Xavier convinces her to side with Lensherr for her to be able to express her mutant freedom.

Or should it be read as: Xavier knew what Raven really wanted (i.e. read her mind), and Raven was simply asking Xavier for permission?

Does the movie suggest that ultimately, the bureaucratic spy will bow down to the operational spy, no matter what differences in opinion there may be between each other?

I think Raven’s changing sides at Xavier’s behest is linked to the whole thing about how he never had to use his powers to know what she was thinking or wanted. Although painting it as him bowing to Erik sounds cooler. That’s just my opinion, though. :)

I do like the parallels, but I think X-Men: First Class is too caught up in its superhero origins to be entirely there. James Bond could arguably be compared with superheros, but not Palmer. And Xavier solves most of his problems by means of his powers, albeit far less directly applied than Lensherr. Even if he doesn’t use them, half the people he’s dealing with know about them, which changes the situation.

oh, and btw, I think you’ll find there was actually a fourth paradigm for spies in the sixties – Maxwell Smart.

oh, and btw, I think you’ll find there was actually a fourth paradigm for spies in the sixties – Maxwell Smart.

For which see Fantastic Four.

Is parody paradigm?

Fascinating article, one tangential and essentially irrelevant question. Why is the abbreviation co-ed used exclusively for female students? Is it some Ivy League tradition or something that filtered into the popular culture? Incidentally, the woman that Xavier tries to, as we Brits say, chat up, would not be educated co-educationally. Although the women’s colleges had been divested of the enforced quota keeping women’s levels low in 1957, and granting full collegiality in 1959, the education was segregated until 1974. The last men’s college became co-educational in 1984. The final women’s college became co-educational in 2008, my first year at the university.

Does that count as a Well, Actually? I don’t know.

Interesting, especially since women were allowed to vote in Britain earlier than here in the States… Hm…

Yeah, it’s very much clear that Oxford and Britain as a whole don’t map onto each other – read social mobility/income/etc. etc. etc. It doesn’t help that there’s now more people in our Cabinet who went to Magdalen College than there are women. Probably more people who went to a much smaller college than ethnic minorities. But that’s the Conservatives for you. (source: http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/standard/article-23873241-beware-a-cabinet-of-magdalen-college-men.do )

But don’t all the bar scenes take place in off-campus bars? I only spent a half year at Oxford, but I know that students from different colleges would mingle at the pubs around town. In fact, I rarely met other St. Anne’s students at the pubs I went to. Not to mention that there’s no real proof in the film that the woman Xavier chats up–or Raven for that matter–are even students. The woman could have been a townie. Raven could have been along for the ride for her protection. I actually thought the Oxford scenes were the most accurately depicted scenes in the whole film–that was exactly the kind of loose scholarship/philosophical bullshit flirting/heavy drinking I encountered while over there. Heavy drinking should be emphasized the most there.

I think that it’s when she talks to Raven that she asks something about her that shows that Raven isn’t a student and that the woman is. A bit like the ‘which college are you at?’ ‘Actually, I’m at Brookes’ conversations today. Except that Brookes people are usually nicer than Uni. The main pub looked like the Tom Tavern/St. Aldates to me, and one was a bit of Hertford that I think was standing in for the Eagle and Child called ‘The Eagle’. Yeah, even fifty years afterwards, I thought the Oxford bits were pretty accurate. The yards of ale were often boasted about by former-Rhodes-scholar professors. During lectures.

It may be that St. Anne’s, which from my experience has a great community spirit, doesn’t need to get out as much/only ever goes to the Royal Oak/whereas the other colleges are desperate to escape (see: Christ Church).

I liked First Class, but one thing about it left me ambivalent: the fact that Magneto is more heroic, and more importantly is more interesting, than Xavier.

Sure, he’s a morally-ambiguous, revenge-driven killer from his first adult scene. And sure, it’s good that he’s a well-developed character. But while he’s hunting Nazis, Xavier is using picking up chicks. While he’s traveling the world to avenge his family, Xavier is building an impromptu school just because he’s a nice guy. And while he ends up with a genuine team of misfits, the ones who stand with Xavier are all able to pass for normal except for one guy who really, really wishes he could. Everything in this movie leads me to support and prefer the cold-blooded monster from the first first three X-Men movies.

Sorry it took so long to respond to this post, but, well, it took me a long time to get around to seeing the movie!

Anyway, what I can’t quite comprehend is why neither the article nor ANY of the comments has yet brought up The Avengers! Bond & the Avengers were the comparisons that permeated my mind throughout the film, both aesthetically and philosophically.

While I haven’t read the Harry Palmer stuff, it seems like all of the imperfections in comparing him to Xavier are solved when comparing Xavier to John Steed instead… and the sense of “working with a team” is certainly heightened. I don’t know if you were only looking at spy *novels* exclusively, or spy *films* exclusively, but I don’t think you can ignore the Avengers series in any discussion of ’60s spies.