This brings us back to Straw Dogs.

Straw Dogs, you’ll recall, is about the lengths a man will go to in order to defend his property. Charlie and the thugs he runs with prove that they’re villains by assaulting Sumner’s property. They shoot at his door.

They throw rocks at his house.

And they smash in his windows.

In each of these cases, the villain, his weapon of choice, and the object of his violence are all pictured in the frame at the same time. Why? Because they’re villains. Violence is part of their identity. We must never forget that they’re violent people – that the infliction of their will upon the world causes damage.

What about David Sumner?

Sumner is inseparable from his violence as well. He uses a long, blunt weapon (a fire poker if the movie’s hewing to the 1971 original) to beat one man bloody.

He splashes some boiling oil on another intruder.

And he nails another intruder’s hand to a wall.

The easiest way to distance our hero from violence, and thus make him more sympathetic, is to cut between our hero, the act of violence, and the result. That’s trickier to do with hand-to-hand fighting than with a firefight, but it’s not impossible. Luke Skywalker did it.

The object of his violence is barely visible.

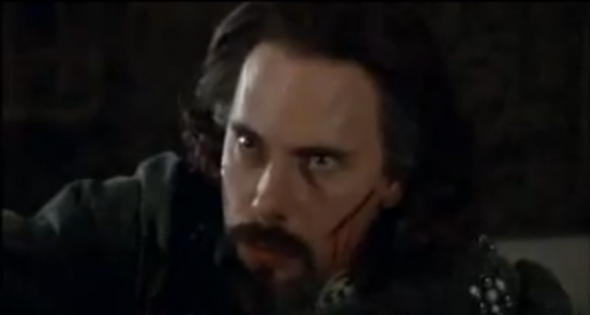

Inigo Montoya did it.

Trust me, I'm getting stabbed.

But with David Sumner, we see the hero, his action, and the result all in the same frame. Why?

As hundreds of critics before me have mentioned, Straw Dogs is a more serious examination of violence than it might first appear. Peckinpah’s intent was not to glorify violence but to exhume it. If you’d asked him, he would have denied that adventurous heroes are reluctant to use violence. He would have laughed at the idea of the Refusal of the Call. The kind of men who use violence to change the world don’t hesitate to do so. They embrace violence just as readily as the “villains.” It’s part of their nature.

While I haven’t seen Straw Dogs (and maybe I should), I have seen The Wild Bunch. And it’s no accident that The Wild Bunch spends several minutes in the beginning introducing us to a quaint Western town. The first line of dialogue is spoken by legendary leading man William Holden. And those words are: “If they move, kill ’em!”

Straw Dogs (at least, the ‘71 version) is the story of a man who secretly wanted to use violence all along. He just never had an excuse. The village bullies tormented and pushed him, provoking him to keep retreating. When he had nowhere left to retreat, only then did he bare his teeth.

It remains to be seen whether the remake, 40 years later, will treat Sumner with the same horror. The trailer suggests otherwise. It implies that Sumner is discovering his true self by indulging in violence. The assaults of the town thugs are a favor to him, showing him who he really is.

Perhaps that’s indicative of the film industry’s changing tone on violence. Violence has gone from being a reluctant tool of heroes – Wyatt Earp taking up the Marshall’s badge; Spartacus pressed into rebellion; Hamlet holding himself back from killing his uncle – to a sign of their prowess. Bloody films aren’t new. Blood-soaked heroes aren’t new. But not every blood-soaked film has a hero. Except the remake of Straw Dogs, apparently.

I agree with you that in Die Hard that’s how heroism is displayed but that isn’t universal film grammar. Not to squabble with one off exceptions, I think more than being in same frame it’s the specific victim in foreground killer shooting towards camera that creates the “badness” of it, as in a theater it would seem like the character is shooting someone in the audience. Because having the person in same frame isn’t enough as in Indiana Jones most everyone he kills shares the frame with him when it happens. But to counter the foreground theory Marion shoots someone in the head in foreground who falls revealing Marion smiling with smoking gun. So maybe it’s foreground impact of *faceless* victim, with lots of tension edited in before the killing?

But it’s like Peckinpah and slow motion death, which he took from Kurosawa who first used it when a kidnapper was killed to underline the humanity of a life lost despite him being a villain, Peckinpah used it to underline impact, and it’s evolved that slow motion death is just to prolong spectacle. Every slow motion death doesn’t equal humble contemplation of the universality of death and every wide shot where someone kills someone doesn’t mean their the villain.

Because having the person in same frame isn’t enough as in Indiana Jones most everyone he kills shares the frame with him when it happens.

I don’t recall Indy doing that much killing. The ones that leap to mind are:

(1) He shoots the swordsman (Raiders of the Lost Ark).

(2) He lets the mechanic get decapitated by the propeller (same).

(3) He shoots four Nazis with one trigger pull (The Last Crusade).

I know I’m obviously missing a few, but Indy slugs far more people than he shoots. It’s not like he’s capping fools all the time. Plus, in the case of #1 and #3, those are shot for comic timing moreso than heroic triumph.

I think more than being in same frame it’s the specific victim in foreground killer shooting towards camera that creates the “badness” of it, as in a theater it would seem like the character is shooting someone in the audience.

This is a good point.

To belabor my nitpick- flip Die Hard: McClain sharing frame, Gruber always separate; we still interpret Gruber as bad- my proof is that very flip is the basis of Yojimbo, the bad guy uses a gun shooting across frames while the hero uses a sword to face his foe directly within frame. In both cross cutting edits deny/distance the violent act, but we interpret that denial/distance as heroic reluctance in Die Hard and cheap cowardice in Yojimbo.

Yojimbo’s hero shares the frame with everyone he kills, and with similar ruthless precision as Gruber or Cruise in Collateral, but it’s morally opposite even though it’s shot the same- this admits that sharing the frame emphasizes repercussion of act, but also that there’s something more in the performances and story that cues the audience how to interpret that act.

I don’t think it’s cherry picking Die Hard when an edit is associative or dissociative because within Die Hard it makes a consistent connection through contrast, but I don’t think it can cut paste to another movie and be the same thing as that editing might emphasize something else entirely given how other story and mise-en-scene elements relate to it within that movie as Yojimbo shows.

But Yojimbo himself is only barely “heroic.” He’s the protagonist, and he’s likable, but he’s a scoundrel who takes advantage of others’ greed and gullibility. Plus, the “swords vs. guns” distinction adds a whole other layer of moral complexity.

The interesting comparison would be with some other classic Westerns. I need to give this some more analysis (follow-up post!). Good comments!

I’m desperately trying to defend my optimism for the Straw Dogs remake as the original felt convoluted (not mistaking morally challenging for muddiness I mean there’s plot clumsiness) the critics gloss over that in justifying it’s very existence as art, but if they can forgive some of the original’s faults why can’t it be done for the remake?

I don’t trust Hollywood as much as the next guy but Straw Dogs is not a flawless masterwork and even if it’s remake is equally flawed it will hopefully be as interesting. Maybe it will be like The Producers, where one has better dialogue and performances and the other really good song and dance numbers?

The biggest issue between the protagonist and the antagonist is emotion. The good guys always have an emotional involvement. Even the greatest stoic performance — can you say Eastwood? — shows emotional involvement for their acts. Violence is the last resort for the pro. The anti’s OTOH have their violence just below the surface. Hair trigger mentality.

As your ref: above for Gruber/Takagi. It’s not the blood or even the framing that makes the impact, it’s Rickman’s brilliant portrayal of a surpreme badass. How do we know? His total blasé attitude in killing Takagi. “Not working? OK, bang! Next choice on my list.”

Gruber is charming, smooth, sophisticated, immensely likeable and totally psychopathic. Classic serial killer profile. McClane is sweaty, dirty, on the edge of panic for most of the movie but overcomes everything to win. He is forced to respond at every turn. David Sumner is the same and so are most protagonists. They are reluctant. That is why they are the heros.

To muddy the waters… is Leon a hero? Is Mathilda? And I have yet to see The Man from Nowhere but that one should upset the applecart for movie tropes.

One other ‘well actually’ that is delightfully off the point of the importance of visual framing.

You note the terrorists in Die Hard kill only 4 people, thus making their villain status morally questionable compared to the hero. You seem to forget the botched mass killing on the roof. They had planned to blow up the entire group of hostages and the FBI helicopter (the latter they were ultimately successful in destroying) with the roof explosion. This was to cover their escape, and was there plan all along, even without McClane’s intervention. Clearly this cold blooded killing of the entire office staff (and likely would have included Takagi, even if he had given the codes) frames Gruber and associates as the villains, or at least shows they aspire to be so. Would this plan of violence not give moral justification to the hero’s bullet filled response, even if not successfully carried out?

One wonders how this movie might have been shot in the form of a caper film, if told from the perspective of a particularly ruthless and smart group of European thieves.