Confession: I’ve never seen Straw Dogs. I’m using it as a point to riff off of, rather than the foundation for my argument. Sorry for leading you on. But I’ve probably seen Die Hard a dozen times. Where Straw Dogs ushered in a new era of cinematic violence, Die Hard marked the start of the action blockbuster. While the stakes could still be grim, our hero could address them with wit and charisma.

Die Hard is the story of a man who sneaks around an office building, murdering ten people before he’s sated. This man is NYPD detective John McClane. The terrorists whom he’s trying to dislodge kill four people: two guards in the lobby, Joseph Takagi and Harry Ellis. The last two, it could be argued, are reluctant kills. Hans Gruber would rather get in and out of Nakatomi Tower without having to kill Takagi, and Ellis is an unexpected hassle. McClane shows no such reluctance.

Unlike Straw Dogs, Die Hard is not morally ambiguous. You never question whether or not John McClane’s the hero. Why is that? McClane kills more than twice as many people as the terrorists and does a tremendous amount of property damage besides. But he’s the hero and Gruber’s the villain. How is that so screamingly obvious?

Put aside for now the question of right and wrong. For one thing, in most moral codes, being in the right does not give one absolute license to use any means necessary. For another, there’s a difference between a movie telling us our hero is in the right – through exposition, perhaps, or the title card – and persuading us he’s in the right. If one of the secondary characters popped in every ten minutes to say, “Boy, John McClane sure is doing the right thing,” Die Hard would be awful. Instead, it’s a classic of American cinema.

I’m not interested in why McClane is the hero and Gruber the villain. I’m interested in how we can tell.

A Question of Distance

Here’s the most brutal thing Gruber does: shooting Takagi in the head at close range when he won’t reveal a password.

Okay.

Note the composition of the image. Both the killer (Gruber) and his victim (Takagi) are in frame. They’re filmed at enough of a distance that both of their torsos are visible. Right now all the details are clear, but in less than a second, there’s going to be a big burst of red that obscures everything.

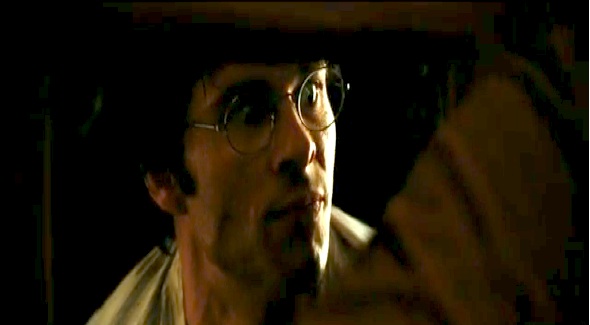

Now here’s the first guy McClane shoots.

This is resolved in two shots. The first shot is a medium shot, showing McClane’s head, arms and half his chest. It’d be a “two-button shot” if his shirt had buttons on it. We see him firing past the camera, but more importantly, we see the panic on his face. Oh no!

The second shot is a full shot, showing our victim and some surroundings. He jerks back, caught by bullets, and falls down. He bleeds a great deal – note the spurts of red – but the blood never obscures our view of the scene. There’s just enough blood to know that he’s met a violent end, but not so much that the scene is dominated by it.

Most of this blood came from Takagi. Really.

This is an important distinction. Our hero and his opponent do not occupy the frame at the same time at the moment of execution.

Of course, there’s more than one bad guy in this scene. McClane’s trapped under a table! He squirms backward while the bad guy stalks him. Then he reloads. He fires straight up through the table, gritting his teeth. Again, two frames: one of McClain firing …

Next time you have a chance to kill someone ...

… and one of the bad guy getting it.

... don't hesitate!

The audience is never confused. Despite the cut between these two images, we don’t wonder what’s going on (“are these different rooms?”). This is the magic of editing at work, as these two shots were probably not filmed at the same time. Marco probably got it on top of the table (squibs loaded up, splinters of wood popping), then Bruce Willis slid underneath to fire some blanks when John McTiernan called “Cut.” But our hero and his handiwork are separated by that cut.

And most of McClane’s kills take place the same way. McClane fires in one frame and a bad guy gets it in the next.

Compare this to Gruber executing Ellis for not living up to his bargain.

Hans, what am I, a method actor?

While the actual trigger pull happens off camera, we do see Gruber picking up his gun with Ellis’s head still in frame. The camera later pans over Ellis’s bloody head while Gruber narrates some demands over the radio.

But when John McClane shoots the penultimate villain in the head …

… there’s almost no blood.

The Heroic Journey (Yes, AGAIN)

While not every action film mimics Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, they all borrow one element of the Hero’s Journey: the reluctant departure, or the Refusal of the Call. Our hero does not want to plunge into action. Maybe he’s a weary veteran. Maybe he’s one day away from retirement. Maybe he’s been saddled with a crazy partner. Maybe Poseidon’s got it in for him.

Our hero uses violence reluctantly if he must.

John McClane is at Nakatomi Tower reluctantly. All of the people he meets are yuppie snobs, though he makes a begrudging exception for Joseph Takagi (and look how long Takagi lasts). McClane wants nothing more than to pick up his estranged wife and get out of there. But when terrorists seize the building, McClane plunges into action to save the Nakatomi employees. He arrives reluctantly, but eventually he embraces the Call to Adventure.

To show the distance between our hero and his violent deeds, a canny cinematographer will depict the hero and his victims in separate frames during firefights. There’s a visual separation between the hero and his bloody work that eases the violence in the mind of the audience. Our hero isn’t killing another breathing human being with hopes and dreams. He’s enforcing his will against a cruel universe, firing his gun into the blank spaces just past the camera. If those spaces should happen to contain henchmen, so much the better.

There are other reasons for breaking up the action into different frames as well. Shooting the hero in a medium shot allows the audience to focus more on his face. This is very important for films like Die Hard, where Bruce Willis’s personality is the biggest draw. We need to see him groan and gasp as he sprints across a hall in panic, laying down a hail of bullets. Violence is never impersonal for him. It’s immensely personal. We need to empathize with his struggle. The bad guys shoot at him from a distance; he shoots at them from the middle ground.

To see what a difference perspective makes, consider the “is that my briefcase, homes?” scene from Collateral:

Vincent (Tom Cruise) executes two muggers in a full shot. There’s an imperceptible break (a jump-cut) between him swatting away one of their guns and him blasting both of them. Later, he picks up his briefcase and finishes off one of the wounded without even looking at him. The shot doesn’t change perspective through out: full shot, good distance, everyone’s figures completely in the frame.

That scene could have been filmed a thousand different ways. Imagine if we’d stayed tight on Vincent’s face throughout, interspersed with some smash cuts of guns being drawn and blood spraying. You’ve seen that before. It’s not odd. But Michael Mann, who’s also canny at setting up a shot, framed it this way. Why?

To remind us that Vincent isn’t the hero.

Sure, we may think he’s a bad-ass in that scene. But it’s not meant to endear us to him. Our sympathy still lies with Max tied up in the cab. The muggers are particularly unlikeable – ugly, brutish, ill-spoken and robbers besides. Vincent dispatches them so that the plot can move along. But when he shoots a guy in the face without looking and comes back to the cab, it’s not reassuring.

I agree with you that in Die Hard that’s how heroism is displayed but that isn’t universal film grammar. Not to squabble with one off exceptions, I think more than being in same frame it’s the specific victim in foreground killer shooting towards camera that creates the “badness” of it, as in a theater it would seem like the character is shooting someone in the audience. Because having the person in same frame isn’t enough as in Indiana Jones most everyone he kills shares the frame with him when it happens. But to counter the foreground theory Marion shoots someone in the head in foreground who falls revealing Marion smiling with smoking gun. So maybe it’s foreground impact of *faceless* victim, with lots of tension edited in before the killing?

But it’s like Peckinpah and slow motion death, which he took from Kurosawa who first used it when a kidnapper was killed to underline the humanity of a life lost despite him being a villain, Peckinpah used it to underline impact, and it’s evolved that slow motion death is just to prolong spectacle. Every slow motion death doesn’t equal humble contemplation of the universality of death and every wide shot where someone kills someone doesn’t mean their the villain.

Because having the person in same frame isn’t enough as in Indiana Jones most everyone he kills shares the frame with him when it happens.

I don’t recall Indy doing that much killing. The ones that leap to mind are:

(1) He shoots the swordsman (Raiders of the Lost Ark).

(2) He lets the mechanic get decapitated by the propeller (same).

(3) He shoots four Nazis with one trigger pull (The Last Crusade).

I know I’m obviously missing a few, but Indy slugs far more people than he shoots. It’s not like he’s capping fools all the time. Plus, in the case of #1 and #3, those are shot for comic timing moreso than heroic triumph.

I think more than being in same frame it’s the specific victim in foreground killer shooting towards camera that creates the “badness” of it, as in a theater it would seem like the character is shooting someone in the audience.

This is a good point.

To belabor my nitpick- flip Die Hard: McClain sharing frame, Gruber always separate; we still interpret Gruber as bad- my proof is that very flip is the basis of Yojimbo, the bad guy uses a gun shooting across frames while the hero uses a sword to face his foe directly within frame. In both cross cutting edits deny/distance the violent act, but we interpret that denial/distance as heroic reluctance in Die Hard and cheap cowardice in Yojimbo.

Yojimbo’s hero shares the frame with everyone he kills, and with similar ruthless precision as Gruber or Cruise in Collateral, but it’s morally opposite even though it’s shot the same- this admits that sharing the frame emphasizes repercussion of act, but also that there’s something more in the performances and story that cues the audience how to interpret that act.

I don’t think it’s cherry picking Die Hard when an edit is associative or dissociative because within Die Hard it makes a consistent connection through contrast, but I don’t think it can cut paste to another movie and be the same thing as that editing might emphasize something else entirely given how other story and mise-en-scene elements relate to it within that movie as Yojimbo shows.

But Yojimbo himself is only barely “heroic.” He’s the protagonist, and he’s likable, but he’s a scoundrel who takes advantage of others’ greed and gullibility. Plus, the “swords vs. guns” distinction adds a whole other layer of moral complexity.

The interesting comparison would be with some other classic Westerns. I need to give this some more analysis (follow-up post!). Good comments!

I’m desperately trying to defend my optimism for the Straw Dogs remake as the original felt convoluted (not mistaking morally challenging for muddiness I mean there’s plot clumsiness) the critics gloss over that in justifying it’s very existence as art, but if they can forgive some of the original’s faults why can’t it be done for the remake?

I don’t trust Hollywood as much as the next guy but Straw Dogs is not a flawless masterwork and even if it’s remake is equally flawed it will hopefully be as interesting. Maybe it will be like The Producers, where one has better dialogue and performances and the other really good song and dance numbers?

The biggest issue between the protagonist and the antagonist is emotion. The good guys always have an emotional involvement. Even the greatest stoic performance — can you say Eastwood? — shows emotional involvement for their acts. Violence is the last resort for the pro. The anti’s OTOH have their violence just below the surface. Hair trigger mentality.

As your ref: above for Gruber/Takagi. It’s not the blood or even the framing that makes the impact, it’s Rickman’s brilliant portrayal of a surpreme badass. How do we know? His total blasé attitude in killing Takagi. “Not working? OK, bang! Next choice on my list.”

Gruber is charming, smooth, sophisticated, immensely likeable and totally psychopathic. Classic serial killer profile. McClane is sweaty, dirty, on the edge of panic for most of the movie but overcomes everything to win. He is forced to respond at every turn. David Sumner is the same and so are most protagonists. They are reluctant. That is why they are the heros.

To muddy the waters… is Leon a hero? Is Mathilda? And I have yet to see The Man from Nowhere but that one should upset the applecart for movie tropes.

One other ‘well actually’ that is delightfully off the point of the importance of visual framing.

You note the terrorists in Die Hard kill only 4 people, thus making their villain status morally questionable compared to the hero. You seem to forget the botched mass killing on the roof. They had planned to blow up the entire group of hostages and the FBI helicopter (the latter they were ultimately successful in destroying) with the roof explosion. This was to cover their escape, and was there plan all along, even without McClane’s intervention. Clearly this cold blooded killing of the entire office staff (and likely would have included Takagi, even if he had given the codes) frames Gruber and associates as the villains, or at least shows they aspire to be so. Would this plan of violence not give moral justification to the hero’s bullet filled response, even if not successfully carried out?

One wonders how this movie might have been shot in the form of a caper film, if told from the perspective of a particularly ruthless and smart group of European thieves.