It's about the bomb.

[This is the first in what may be a series. Should I have started with a more well-known anime like Sailor Moon or Dragon Ball or Pokemon? Maybe. But I just watched Paranoia Agent, and you should, too. You can stream the full 13 episode series for free on Veoh.com. You won’t regret it.]

[Also: this is a SPOILER FREE! article. Hopefully it’ll make you want to watch the show.]

First, a story…

Back in college, a friend of mine asked me to take a course on modern Japanese literature with her. Being my snarky self, I said, “Why should I do that? I already know the answer to all the books. If I took this class, I guarantee all of the essays would have the same exact thesis:

‘It’s about the bomb.’”

Whether or not I was right about modern Japanese literature, the interesting thing to me is how little this thesis applies to anime and manga. There’s the odd exception, of course; Grave of the Fireflies jumps to mind, as does Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress. (Grave of the Fireflies is about two children trying to survive through World War II; Millennium Actress is about an aging actress who lived through the war.)

For the most part, though, anime goes out of its way not to mention nuclear weaponry. Never never never. The most blatant example is the famed Neon Genesis Evangelion, in which the main characters continually use nukes but never refer to them by name. No, they’re “N-2 mines!” Nothing nuclear about ‘em! Those mushroom clouds over there? Just a trick of the light! (In case you don’t believe me about the nuclear weapons taboo in anime, here’s an article about it on TVTropes, appropriately titled “Nuclear Weapons Taboo.”)

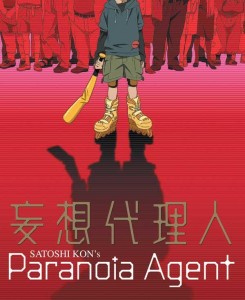

So I was shocked by Satoshi Kon’s anime series, Paranoia Agent, for two reasons:

1. It is clearly about the bomb.

2. None of the reviews or articles I read about the show acknowledged this fact.

If you’ve never heard of Satoshi Kon before now, put his name in your memory file, because he’s one of Japan’s directors to watch. His first film, Perfect Blue, catapulted him to fame and glory, giving him free rein to work on even crazier postmodern pieces like Millennium Actress and Paprika.

Critics have lauded Kon for blurring the lines between fantasy and reality in his work, which by the way is always quite beautiful. But blurring fantasy and reality is nothing new, even in anime. You only have to watch Neon Genesis Evangelion to know that. Kon’s work is beautiful, but so is a lot of anime. Kon’s works are also quite referential; he loves pastiche and parody. But that’s not new in anime, either. FLCL, The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya, and Excel Saga, ahem, excel at mocking anime conventions through the form of anime.

What’s new about Kon’s work is how modern and sociopolitical it is. However you define art, Evangelion certainly fits the bill, but it’s more a psychological drama and religious allegory than a critique of modern Japanese society. While Haruhi Suzumiya is all about undermining common anime tropes, the show seems to be more parody for parody’s sake, not to make any larger statement about the people who enjoy the original product.

Which brings us to Paranoia Agent. Here’s the story, briefly: An elementary school boy—the Shonen Bat—supposedly has been rollerblading around Tokyo and its suburbs to make hit and run attacks with his baseball bat. A bunch of people have been hospitalized as a result, and soon people start dying. Although the anime starts out as a simple mystery (“who is the Shonen Bat?”), it quickly becomes complicated as the audience and the police realize that all of the victims have one thing in common: they feel boxed in and are looking for some way—any way—out, even if it means being bashed over the head with a blunt object.

There’s a lot to pick apart in the show, particularly the fact that the Shonen Bat’s first victim is Tsukiko Sagi, the designer of Maromi, a cute stuffed dog that is clearly meant to be Hello Kitty, Pikachu, Luna from Sailor Moon, and Totoro all rolled into one.

Then Maromi comes to life and starts talking to her.

Then things get weirder.

Maromi is not creepy.

As a postmodern text, Paranoia Agent begs to be interpreted. According to the reviews and articles I read, the show is about alienation, personal responsibility, the cult of victimhood, and Japan’s preoccupation with fantasy and cuteness. This is all true. Paranoia Agent is clearly about all of these things. But you know what else it’s about?

It’s about the freaking bomb.

How do I know that? Well, the show’s opening tipped me off:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=waTi95SEWJA

For those of you who don’t feel like watching it (even though you should—it’s about the weirdest opening sequence I’ve ever seen), here are the translated lyrics to the theme song:

“The lost children are a spectacular mushroom cloud in the sky/

The lost children are comrades to the little birds that have infiltrated these lands/

Touching the sun-kissed law with their hands/

They are trying to speak with you/

Dreams bloom atop benches in the apartment complex/

Hold your fate inside your heart/

Quell your depression/

Stretch your legs out towards tomorrow/

Don’t worry about things like tidal waves/

The lost children are a spectacular mushroom cloud in the sky/

The lost children are comrades to the little birds that have infiltrated these lands/

The lost children are dreams grown atop benches in the apartment complex/

The lost children are comrades born on the day of the light that filters through the trees.”

Okay, let’s pick it apart. “Lost children.” That can refer to today’s youth, Japan’s so-called “Lost Generation” of young people who are having trouble getting full-time jobs and making ends meet. This is also the generation raised on the Internet, the generation that spends more time on World of Warcraft or text messaging than interacting with real human beings.

And that fits with the themes of the show, sure. But what about that “spectacular mushroom cloud in the sky”? The “birds that have infiltrated these lands” (like that bird named Enola Gay, perhaps)? “The light that filters through the trees” can be interpreted as a simple image of sun coming through the leaves on a spring day… or the light of the atom bomb flash frying an entire generation. And just in case you didn’t get the bomb connection, the intro sequence has debris and a mushroom cloud in the background.

“But Shana,” you may be saying. “Even if the theme song IS about the bomb, who says theme songs directly reflect the themes of their shows? Even though MASH’s theme song is called ‘Suicide is Painless,’ MASH is not about suicide.”

That’s true. We can’t interpret a show primarily by watching its opening sequence. We must also look to the actual text. I’m not going to say much because I don’t want to spoil the show for you, but in the very last episode after the series’ climax, one of the main characters explicitly says, “It looks like just after the war.” Which war? I’ll give you three guesses.

According to the reviews and essays on the show, the theme of Paranoia Agent is something along these lines: “People in Japan (or maybe all humans) screw up because their lives are so full of pressure and because they are alienated. But they don’t want to take responsibility for their actions, so they cry victim so they don’t have to change their ways. And to comfort themselves, they escape to adorable and superficial anime shows.”

I like that reading. Early in the show the police realize that the Shonen Bat’s victims LIKE being victims. One of the police officers says something like, “They all seem kind of relieved.” Being victims of a crime allows them to give excuses for not getting their work done, for being bullied at school, for failing to pay back a debt in time. One victim is bashed into amnesia, freeing her from all responsibilities and stress. And, of course, lots of victims just die.

But let’s add the bomb to the mix. The theme of the show is: “Japanese people treat themselves as victims and try to console themselves with anime.” Now add the bomb: “Japanese people treat themselves as victims and try to console themselves with anime BECAUSE OF THE BOMB.”

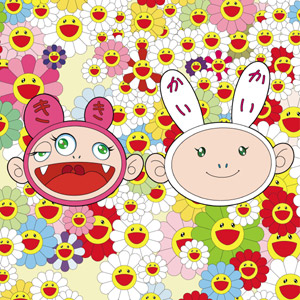

Superflat art from the Brooklyn Museum show.

This theme is not new. It’s one of the major ideas behind the Superflat movement in the fine arts, founded by Takashi Murakami. “Superflat” is a complicated term. It refers to the flatness of anime and manga art, which goes back to traditional Japanese watercolors and ink pieces. Traditional Japanese art is two-dimensional, as is anime. At the same time, it refers to Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s becoming, literally, super-flattened by the bomb. At the same same time, it refers to the supposed superficiality of anime culture and its over-reliance on the cute (or “kawaii” in Japanese). Anime is superflat because it has no intellectual depth. Get it? In both Paranoia Agent and in Murakami’s work, feelings of alienation and sexuality are inappropriately channeled into anime, manga, and video games—Japanese consumer culture. And where did these bad feelings come from? From the stresses of high school entrance exams, from the stress of work in the not-so-great Japanese economy. Oh, and from BEING BOMBED.

Those are the claims of Paranoia Agent and the Superflat movement. But I wonder how true these claims are. Do Japanese people treat themselves as victims any more than any other people? If so, is it because of the bomb or because of something else? Is it unique that Japanese people seek solace in the cuteness of anime, or is that something that all people do? And if Japanese people are unique in their love of anime, is that necessarily because they were nuked? In short, do all of the meanings of the term “Superflat” necessarily connect?

It is true that anime developed during and after World War II, but that seems a quirk of history rather than causality. In other words, Japan did become obsessed with the cute after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but does that necessarily imply that kawaii culture came about because of the bombings? I’m not so sure about that.

On the other hand, it is true that Japan is the anime capital of the world, and cuteness seems to hold quite a bit more sway there than anywhere else. Anime is getting quasi-popular in the U.S. now, but not so much that we see suited businessmen reading manga on the subway. We Americans also seem to enjoy the violent Dragon Ball/Naruto stuff more than the cutesey Totoro/Hello Kitty stuff, if Adult Swim’s anime lineup is any indication of our tastes. Perhaps we Americans sublimate our troubling emotions and repressed sexuality into violent action movies while Japanese people prefer My Neighbor Totoro and Card Captor Sakura.

I am not Japanese, nor have I ever lived in Japan. So I need proof. If you are Japanese or have more knowledge of Japan than I do, do you think it’s true that Japan’s cute obsession stems directly from World War II and the atom bomb? If you are from another non-American country, can you speak about your experience with cute culture? In other words, are anime’s infantilism and cutesiness unique? Are modern Korean and Chinese cultures that different in this respect? I mean, almost every culture has gone through terrible times, but not every culture flees to cuteness. I haven’t seen any Jewish anime yet. But, hey, there’s still time!

And a question for everyone, regardless of where you’re from: do you think different countries have clearly defined popular cultures? Is it right for me (or Satoshi Kon, or Murakami) to define Japan by anime and manga? Is it okay to extrapolate on an entire country’s psychology based on its assumed preoccupation with one aspect of pop culture? If so, what does our American pop culture say about us?

Hello,

I’m pretty late to this, but I really enjoyed your analysis. I don’t know that I can really give a better perspective about the “cause of the cute,” even though I have lived in Japan for 2.5 years. But the notion of responsibility and being relieved by the idea of being a victim resonates, for sure. Consider, also, Japan’s continued resistance to making formal apologies to Korea and China for things like Nanking, etc., and you can easily start to see Japan in that light: “Well, yeah… but we were NUKED!” That’s a gross oversimplification, but I think it works within your analysis of Paranoia Agent rather well.

I haven’t watched this in a couple of years, but I’m going to start again. Thanks for giving me a new angle on the show.

–Matt in Nara

Oops… somehow I thought you’d posted this a long time ago. So I guess I’m not so late after all! (sorry to double post)

I thought Paranoia Agent was blatantly obvious with being about the bomb that it wasn’t even worth mentioning.

“If so, what does our American pop culture say about us?

” LOL…that is so funny. I can’t believe you actually asked!!!

@TheDarkFan: Why?

Thanks to this article, my girlfriend and I watched this anime and we loved it. I think your analysis was spot on and what especially impressed me about this anime was the multiple levels that it worked on. Thanks very much!

I know very little about Japanese culture and anime (I liked it when I was a child, grew out of it for the most part) but having recently seen the animated adaptation of Barefoot Gen, I’m now kind of wondering if it was less “we’re anxious because of the bomb” and more that “Shonen Bat himself was a metaphor for the bomb.” Keiji Nakazawa, the creator of the semi-autobiographical manga Barefoot Gen (about the Hiroshima bombings and the aftermath thereof – Nakazawa was a young boy living in the city when it happened) said something along the lines of “wanting to speak up and place some responsibility on the Japanese people for the bomb” and going on about how it was a result of the Japanese government stubbornly continuing to fight a hopeless war, causing day-to-day suffering even for the Japanese people, and they drove the Americans to take drastic measures to end the war. The dichotomy of the completely unfathomable horror of what he experienced and his attitude that it was kind of a relief that it happened, and also somewhat their own fault, was very shocking to me … much like the dichotomy between Shonen Bat murdering the victim and the victim seeming kind of relieved.

Maybe Satoshi Kon has the same kind of thoughts about it. From this point of view, maybe Paranoia Agent is about trying to deal with this troubling pseudo-masochism and/or the inability to take their share of responsibility for the bombing. (By regressing into “cute culture” and harboring denial?) It’s hard just for me personally to wrap my head around Nakazawa’s idea that the Japanese brought something as terrible as Hiroshima and Nagasaki on themselves. It’s got to be a lot more difficult for an entire culture, the culture that it actually happened to.

It’s interesting that the theme song refers to the lost children as being *comrades* of the little birds/American war planes, as in, supporting them and what they’re trying to do.

Interesting take but I’ve checked several sources that have translated lyrics that differ significantly from yours in various areas. I’m not saying who is wrong or right, but could you show us where you derived your translation from?

This was an amazing review. I had just rewatched the anime, and after receiving more understanding through additional experience, your review has me trying to interpret on an entirely different level. I’d love to pick and poke at every part of your review, and add my own two cents, but if people wanted that, I’d have my own review. Let me just say that you’ve done something amazing here, and hopefully the benefits you have given others will return to you tenfold.

Still an insightful read after all these years. I found this article after watching Paranoia Agent back in college and wanted to understand it better.

Satoshi Kon was a real visionary and there won’t be another director like him who produces such unconventional anime, though Masaaki Yuasa might be a close second. Kaiba, Tatami Galaxy, Ping Pong the Animation are just as thought-provoking as it is bizarre.

Me and my friend loved this article! we just finished the show and decided to pop corn read this on a whim. very insightful!

You just made a lot of assumptions. And just to be clear, Japanese were the victims and USA was a sh*t for the bomb

Japanese Language and Literature major here… I don’t know where you got your lyrics from but they are really badly translated almost comedically so in order to get the bomb point across.

You’re article is very informative and thought-provoking. Even if the lyrics aren’t 100% accurate, it was still a very entertainment read! Even so many years later, this was a blast!