When blogging for OTI, I try to avoid talking about the economic factors that go into the production of art. Economics can seem simplistic – like a “just-so story” – or reductionist. Why does The Walking Dead spend so much time at the campsite? Because they had a limited budget and could only shoot on a few sets. Done! Hit “Publish” and kick back until next week. When all you have is a bachelor’s degree in economics, everything looks like a widget factory.

But when talking about the overall logic of why one show succeeds and another largely identical show fails, economics can’t be avoided. You have to talk about what the market looks like, who the biggest producers and consumers are, and how the incentives line up.

From the earliest days, the role of commercial broadcasting has been to sell consumer packaged goods. Whether cigars (William S. Paley and the CBS radio network), home stereos (RCA and its NBC network) or laundry detergent (the “soap opera” genre), advertising has been the stream that keeps television alive. Advertising dollars are the reason the size of an audience matters. Larger audiences mean more ad exposure, and more ad exposure means a lift in brand awareness and sales.

Advertising is not an afterthought in the TV medium, any more than gravity is an afterthought in air travel. Advertising does not simply dominate broadcast television. Advertising is the reason television exists. $9.9 billion was spent on advertising in broadcast TV in Q3 of 2010 alone. Q4 numbers aren’t available yet, but if the total ad dollars spent on TV in 2010 was less than $50,000,000,000, I’ll spot you the difference.

The mere presence of advertising doesn’t change a medium. Summer stock theater companies take out quarter-page ads in their programs to defer the cost of stage lights, but no one accuses the Shreveport Players of being sell-outs. Tina Fey, Robert Carlock and the other writers of 30 Rock didn’t get into TV writing in order to sell more washing machines. And the thousands of auditioning hopefuls on American Idol, as silly as we may find their ambition, didn’t wake up that morning hoping to shill for Coca-Cola.

But you don’t need to love a product when the product dictates the medium. When you put a writing team in the same room as $50 billion in annual ad revenue, the money talks a lot louder. If you think you can talk louder than the money, then try writing a sitcom script that runs longer than 24 minutes.

(And some folks don’t mind selling out. George Axelrod, writer of the screenplays for Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Manchurian Candidate, used to write for radio sitcoms. An ad man offered him a case of scotch every time a certain product was mentioned in the course of the show. So Axelrod introduced a recurring character named “Maybelline Mascara.”)

So: the point of primetime television is to sell consumer packaged goods. Who buys consumer packaged goods? Middle class Americans. The working poor don’t have a lot of disposable income; the truly affluent don’t care. But when the middle 60% of America stares at the shelves in their local grocery, they need something to distinguish between one brand of toilet tissue and another. Is it the softness of the sheets? The hint of lotion or pleasing scent? The density of the tissue? The number of sheets per roll?

That’s where advertising steps in.

Television is such a universal presence in America that it’s hard to think of TV viewers as having identifiable traits. But, in a broad sense, they do. Primetime TV viewers tend to have jobs. They’re likely to be members of families. Those two data points right there make them the target audience for a large quantity of household items: major appliances, minor conveniences, snack foods and soda water. And marketers can save a lot of money by making sure their ads for washing machines are viewed by people who can afford them.

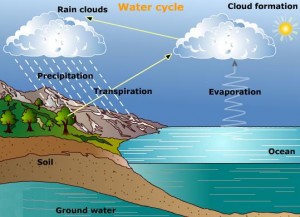

So if the money defines the medium, then the medium follows the audience. You could diagram it like a water vapor cycle. Consumers spend $78 billion on Proctor & Gamble products in 2010. P&G takes at least $8 billion of that to spend on marketing. Of that, P&G probably spent about $2.7 billion, maybe more on TV advertising. Television networks take that $2.7B, along with $48B from other advertisers, and use it to fund shows. These shows are watched by millions (formerly “tens of millions”) of households, which then buy consumer products.

The role of marketing dollars in primetime broadcast television is inextricable. Yet we don’t give it much consideration when thinking about the type of art that broadcast TV produces.

Cable still relies on advertising for revenue, but less so than broadcast TV. This is why you’ll find a diversity of styles, voices and stories on cable. This is why, for example, Treme, a notoriously dense series about an artistic neighborhood in New Orleans, debuted on HBO instead of CBS. This is why Comedy Central features late 80s Tom Hanks movies, second-tier stand-up comedians and cartoons spewing obscenities, all of which would be a hard sell to NBC. Each channel can find its own market, rather than competing for the same slice of middle class America.

Cable didn’t used to be a source of fresh, experimental voices. But as more money flowed into cable, a greater willingness to experiment was born. Cable companies are smaller holdings of larger media empires – Viacom owns Comedy Central, BET, MTV, Spike and Nickelodeon among others. Each of those has (limited) license to pursue its own agenda because it’s a smaller piece of the pie. Sumner Redstone’s not going to go hungry if the latest episode of 106 & Park makes a joke about Hillary Clinton.

I know you were worried about him.

So while money dictates the medium to a certain extent, your ability to command a niche audience gives you freedom. And that, to bring it back to the beginning, is why Netflix is producing helming a TV series.

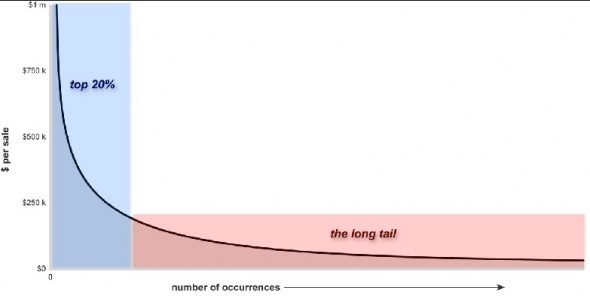

Netflix has made its millions on “long tail” order fulfillment. For the dozen of you who don’t care about Web 2.0 economics, the “long tail” describes the buying patterns of consumers when faced with a wide variety of (certain types of) products. Take books, for instance. Hundreds of thousands of people buy the latest Harry Potter novel. Tens of thousands buy whatever Lee Child puts out. And a few thousand buy the work of Joe Abercrombie. This pattern continues to dwindle until you get small-press books at the far end of the curve that struggle to sell a hundred copies a year.

Work this and 'Six Sigma' into your conversations at work to sound like more of a douchebag.

Amazon.com (since we’re talking about books) didn’t destroy Borders by selling thousands of copies of Harry Potter. They destroyed Borders, and smaller bookstores worldwide, by being the best place to find the books that no one else had in stock. Conventional bookstores couldn’t afford to stock a book that nobody wanted – inventory space is one of the most important costs to manage. But to Amazon and its network of wholesalers, all books are equally accessible. Amazon makes its money off the long-tail: being the most reliable source for the tens of thousands of books that nobody’s ever heard of.

Netflix is in a similar position. Big box retailers and DVD sellers are trying to take some market share back from Netflix by forcing licensing agreements on them: they can’t release the latest hot movie until every other store has had it for four weeks. But that doesn’t matter. Customers don’t pay Netflix $9.99 a month to get their hands on new releases. They pay Netflix so that movies that have been out on DVD for six weeks – or six months, or six years – can get delivered to their house. Netflix doesn’t make its money on the hottest 1% of the market. They make it on the lukewarm 99%.

When it comes to niche audiences, Netflix has a unique advantage. They can command every niche.

Viewed in this light, Netflix is perhaps the perfect home for a character-driven political drama based on a British series that’s more than twenty years old. Any given cable network that took a chance on buying this series would have to hope that its audience would go for it. But Netflix’s genius is in aggregating audiences. Criterion classic snobs, buddy comedy fans, action fanatics and chick flick sweepers all tune into Netflix for what they want. If a remake of House of Cards can’t find an audience on Netflix, it can’t find an audience anywhere in America.

And maybe the success of House of Cards will be a lesson to the Arrested Developments and Fireflys of the world. Quality, integrity and originality aren’t enough to make your show a success. You also have to make sure you’re targeting the right audience. And, to a growing extent, that audience is not watching broadcast TV.

Without knowing for sure, I’m guessing the difference is that Arrested Development costs a lot less than a lot of the FX fare. Louie, in particular, is dirt cheap to produce.

Ditto for Firefly, which was pretty expensive for its time, as well.

I take it you meant “Arrested Development costs a lot more than …”

Which it almost certainly did, but it didn’t have to. It could have just as easily been set in Miami – a city identified with real estate booms, vapid wealth and wacky characters. The cast was largely unknown until A.D. put them on the map. And there were only a few recurring key sets: the model home, Lucille’s apartment, the Bluth offices. Sometimes the prison.

(Slightly off-topic): The recurring sets in Arrested Development lend themselves naturally to a Clue boardgame adaptation…

Oh, wait, someone did that, and it’s awesome:

http://pleated-jeans.com/2011/01/31/arrested-development-clue-board-game/

Want.

With Battlestar Galactica, do we not need to ascribe some value to the fact it was a remake? While the original wasn’t a great success it did build up a fair amount of cult appeal and cultural awareness, so it might well have snared extra interest in the early broadcasts boosting ratings.

Would the recent versions of The Karate Kid and The A-Team have been made/equivalently successful with different titles?

… there’s something to that, but that just leads to the same question back again. Why did the Sci-Fi channel remake of BSG succeed, while the NBC remakes of The Bionic Woman and Knight Rider failed?

Well, to be fair, The Bionic Woman and Knight Rider kinda sucked. Though the original Bionic Woman pilot that leaked online with Ann “her?” Veal playing the deaf sister was unintentionally hilarious.

I often wonder about niche programming if there’s a better way to leverage the passionate fan. There was money to be made off of Firefly… somehow. Lots of those crazy browncoats have an attitude of, in the parlance of Futurama, “shut up and take my money” to anything with Firefly/Serenity on it. And of course every actor in every Sci Fi show ever has a side income for life doing autographs at nerd conventions. So since this money is out there, in some way the passionate fan should be worth far more than a casual viewer to the company making the show in the first place. They do licensed comic books and board games and online content and all that, but that all seems a drop in the bucket compared to the cost of making a TV show. Other than (I assume) being more likely to buy the DVD of a show they’ve already seen, I don’t see that turning into real money that might keep a show alive.

Things like kickstarter fascinate me in this respect, but we’re so accustomed to getting TV for free or from a subscription model, that the number of people to drop cash to help get a series made in the first place is probably miniscule (and the hippie environmentalist in me knows people don’t change habits like this very easily).

This obviously occupies far too much of my brainspace for someone who doesn’t work in entertainment, but it seems completely appropriate for a website with this name.

This comment reminds me of something I discovered in a TV analysis class back in college (unfortunately, it was years ago and I can’t remember the source, so you may have to take my word for it.)

An advertising firm did a study in which they showed television episodes to two groups: one group of fans of the show who never miss an episode, and one group of casual viewers. Afterward, they asked each group to identify what bands they’d seen advertised during the commercial break – and the fans were able to name far more brands with far more accuracy. So, it’s actually more profitable (in terms of raising brand awareness) for advertisers if they advertise for a show with a few devoted fans, than for a show with many casual viewers.

I keep hoping that somehow, the industry will do away with their whole system of Nielson ratings and sweeps weeks – but for the time being, I guess we’re stuck with a broken system.

Inside: the industry will have to. There’s so much rapid growth on demand-side advertising that the money is naturally shifting there. TV will discover a better model to price advertisements than “sweeps week!” within 3 years or will die on the vine.

How much of that passion and willingness to buy anything comes from the fact that the show they love so much has been cancelled, though, and thus they have a “take what I can get” mentality? I feel like at least a little of it comes from the fact that the show is over.

John, great article, but you missed a golden picture caption joke opportunity:

“Proctor and Gamble makes it rain. They make it rain they make it rain they make it rain.”

Firstly, your link to the netflix announcement is borked.

More importantly, in Netflix’s announcement they explicitly say they’re not producing it. They’re just licensing the streaming rights before it’s even produced. http://blog.netflix.com/2011/03/house-of-cards.html Normally they license their streaming deals from the networks but in this case Netflix made an end run around HBO to get the streaming rights because the show is still unproduced.

So while I’d like to see Netflix produce shows it’s still not on their public roadmap.

Fixed both – thanks!

I realize this is a bit off-topic, but I have heard a lot of calls for Netflix to start re-producing cult hits, like Firefly and Arrested Development.

While I would love having new episodes in theory, I wonder how these shows would change without the constraints of a network – no Standards & Practices means more cursing, sex, and violence. The idea that keeps sticking with me on that thread is the Chinese curses of Firefly; granted, I’m sure Joss Whedon and co. intended it at least partly as a preview of the future of globalization, but they could just as easily (in new episodes) have Mal calling out “F*** you!”.

There’s also essentially no time limit, which may drastically change the story structure since you don’t have to create act breaks around commercials. Are new episodes still going to be 22 or 44 minutes long?

Without the limitations of a network, the content producers might not be pushed to the same level of creativity.

While producing in a non-network format might free directors from the 22 or 44-minute constraint, I think that’s still something audiences will look for. Even “sitcoms” on premium networks (like Californication or Curb your Enthusiasm) are nearer to 30 minutes than, say, 38 or 52.

Not to mention that Whedon’s own online Dr. Horrible’s Sing-A-Long Blog was produced in three 15-minute segments, mimicking the 44-minute constraint even though it didn’t have any commercials.

I would say that the 80’s Tom Hanks films and stand up comic specials on Comedy Central are pretty “cheap” shows to broadcast; whereas the Daily Show and the Colbert Report are the budget hogs – mostly for the salaries of the hosts.

Comedy Central used to have much more original programming (reno 911, strangers with candy, etc) that they no longer invest their time or money into. Roasts of Donald Trump are cheaper.

The problem is the cost: $100 million for the rights to stream a niche show with limited appeal is a lot of money, even for a growing company like Netflix. Just to break even they’d have to attract a million subscribers for a year.

http://deemable.com/stuff/2011/03/netflix-and-%E2%80%98the-house-of-cards%E2%80%99/

Before we anticipate the return of beloved cult shows (you can’t take the sky from me!), I think the economic implications of approaches like this need to be thought through more clearly. The main issue that I see is that Netflix is a pure subscription model — it doesn’t matter to them if you subscribe to watch one show or their entire library (indeed, that’s not completely accurate, as bandwidth costs mean they would greatly prefer you to subscribe and not actually use their service at all). Contrast this with a traditional TV model, where what the broadcaster gets paid (in ad revenue) depends greatly on how much of their offerings are actually watched. Perich of course makes this clear in the article, but I think what is not clear is the impact this will actually have.

I’d argue that the most obvious result will be to push Netflix (or similar endeavours) to have a very broad but shallow pool of original programming cutting across a wide variety of genres, rather than having multiple shows that would capture similar audiences. The goal of Netflix is to broaden its subscriber base, not actual viewership, and so there is no reason for it to have both, say, Battlestar Galactic: The Return and Firefly: The New Adventures, since both shows cover similar audiences. The marginal increase in the number of subscribers one might see for producing both shows would be less than producing only one of them and another in an entirely different genre (say, Party Down Again, or even, god forbid, Eight is Still Enough).

Contrast this with the networks and other broadcasters, who make money primarily through eyeballs watching ads. Sure, this model drives a certain kind of programming, but it also means that, at every half-hour, the broadcaster needs to produce shows that will capture the most eyeballs, and if programming a solid evening of sitcoms, or sci-fi, or dramas will do that, then so be it. There will always be a direct financial benefit to producing a well-watched show, even if its audience overlaps with other shows on the network. The networks want to maximize viewing time. It doesn’t matter if same folks who watch House also watch Lie to Me. But for Netflix, having shows with that kind of audience overlap would be a waste, as it wouldn’t actually increase their subscriber base.

The best analogy I can think of for this is comparing a traditional restaurant to a single-price all-you-can-eat buffet. As far as the buffet owners care, once you’ve paid your entry fee, they’ve “monitized” you as much as they are going to, and so their incentive is to get as many people through the doors as possible. They do this by offering a wide range of cheap-to-produce food — none of it is of particularly high quality, and no single menu item is really a draw, but that doesn’t matter, as they don’t really care what you eat (or even if you eat), and they get folks in by the variety, not quality. By contrast, a traditional restaurant is more like a traditional broadcaster — they make more money the more you consume, and the goal is to get you to eat as much as possible. On this model, you can specialize, since you can differentially price your items (i.e., ad rates) to recoup higher production costs, and variations on a single cuisine are rewarded by return business.

I don’t know about you, but I generally much prefer the food at traditional restaurants over most buffet joints, and I think that ultimately boils down to the different economic models. As I see it, while the announced project is fascinating, the economics of the Netflix subscription model is going to mitigate against this kind of expensive quality programming, or at least multiple shows that appeal to the same audience (that would be like an all-you-can-eat buffet that has a section for various lobster dishes).

I only checked out House of Cards because Fincher was remaking it, but I literally checked it out from my local library so nobody made a dime.

Short answer: the prices would be different if there weren’t a resale / used / rental market at the tail-end of the retail pipe; also, enjoy, it’s a lot of fun!

Long answer: [over 100 years of price theory]

Great article! I have one small gripe, though… I don’t think a single episode of Arrested Development, even in the slightly off-pace-at-times season 3, was ever “phoned-in”. Despite the weirdness of season 3 in places, the humor and writing is still as strong as ever.

That’s it!

I’m convinced that Freaks and Geeks was canceled because its niche market – former D&D geek mathletes who became stoners in the early 80s – was just too narrow. Basically just me.

“Firefly, another show that Fox canceled too soon, was a space western produced by Joss Whedon, who had risen to prominence with shows like, wait, do I even need to gloss Firefly for this audience? You know all the details, right? Okay, I’m just going to skip to the analysis.”

That made me very, very happy.

More on point, though. What about YouTube? The first full-length, produced-exclusively-on-YouTube feature premiered last weekend, “Girl Walks Into a Bar.” Free subscriptions to that one, although more advertisements than Netflix.

Also, if niche audiences aren’t money-makers, why does Castle have some sort of blatant fanservice Firefly reference every so often? The thing with Castle is it’s highly obvious that the writers are writing for Firefly fans, not only simply because Nathan Fillion is the star. It becomes apparent with the themes of the episodes, even without the “space cowboy” costumes and spas named “Serenity.” Steampunk, aliens, vampires, comic books… They’re writing for a niche, but it’s doing swimmingly- or at least well enough to have a fourth season in the works. Is this because they knew they’d get the Firefly geeks (like me) from the beginning and (literally) banked on them sticking around? But then there are all those other viewers that make it financially worth it- where are they coming from? Its ratings have gone down a bit (until this past week- the premiere of Dancing With the Stars gave it a huuuuge boost), but they’re still, on average, fairly high (right?).

Oh yeah, and there is also this:

http://helpnathanbuyfirefly.com/

I think those Firefly references appear in Castle because Nathan is a huge promoter, and not because the producers want to bring in the horde of fans, since there isn’t a horde of fans (just a loyal but small cadre of Browncoats). Castle is precisely the kind of bland, comforting, plot-by-numbers TV fare that would do quite fine without the geek references (and if you want references to geek culture on mainstream shows, CSI was way ahead of Castle</i).

And the mention of Castle prompts me to offer a counter-argument to the oft-repeated OTI mantra that the gang likes “actors who work”, and not those prissy folks who only do “meaningful” projects and refuse to participate in pop culture schlock. That stance fails to take into account the deadening effect of working with lousy material on an actor’s craft. Watching Nathan Fillion mug his way through episode after episode of the lazily-plotted, ham-fistedly-written Castle is outright painful, and I cannot help but think that such terrible day-in, day-out work dulls an actor’s chops. Fillion will be a worse actor when he comes out of Castle (in addition to whatever effect the show has on his more serious opportunities). Doing crappy work of any kind numbs the soul, and not every sort of experience hones one’s skills — sometimes it just makes you lazy.

(And yes, I am a Browncoat who watches Castle, and after each mediocre-to-terrible episode I tell myself that I value my self-respect too much to watch another. Seriously, I don’t care how much I adore Nathan, this is the last damned one…)

That does make a lot of sense. So why do you think the producers give into his demands?

My guess is the producers do it because Nathan is a nice guy and the co-star, and the occurrences are very minor and subtle references that aren’t at all noticeable by a non-Firefly fan — they don’t materially interfere with the main audience’s understanding of the scripts, but are just tiny Easter eggs.

I still geekgasmed when this happened:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Q3pdj9p6yI

I suspect they hired him in the first place because they liked his previous work. So I wouldn’t be surprised if they threw those things in because they liked Firefly too.

And, while the Firefly audience is apparently not enough to carry a show, adding a chunk of the Firefly audience to the existing audience of a mildly amusing crime procedural can make the difference between cancellation and the successful-but-not-quite-a-hit status that Castle enjoys.

“Advertising is the reason television exists”

…ironic that you assert this whilst starting the article referring to a BBC-produced program.

advertising may be what sponsors US-based TV, but the bbc manages to produce a ton of (often reasonable-quality) content. thanks be to UK tv license payers… (from original audiences as well as from US “re-makers” :P )

This is a good point, but the very way it does television is not particularly easy to disentangle from the influence of commercial television.

There’s been a lot of talk about the economics of shows getting cancelled in one of the communities I frequent. Genndy Tartakovsky’s latest animated show, Sym-Bionic Titan, over the course of 20 episodes, got the unannounced timeslot shuffle and executives claiming that it failed to sell enough merchandise (because none was available for sale). Of course, among the fans there’s a lot of grumbling like, “Well, I watched it every week” or “I would have bought toys if they were available.” However, there’s also the issue that the majority of us were much older than the target audience. Sure, you have some teens and college kids watching it, praising the ‘mature’ (relatively speaking) storyline and the quality of the animation, but no amount of letters or calls from a bunch of us really matters, because the executives want kids to be watching it.

So Cartoon network, without a hint of irony, continues to renews its dirt-cheap live-action shows and import cheap Canadian shows, and the cycle goes one.

I still say they jumped the shark when they started airing live programming. WTF, Cartoon Network?