I never beat the original Metal Gear for the American NES. The timing and patience required for stealth gameplay on an 8-bit console was beyond my pre-adolescent skills. The initial stage of the game was unforgivingly difficult as well – having to sneak past several guards, defeat some dogs in hand-to-hand combat, and then climb aboard a truck without being spotted. As such, I never made it past the mercenary mini-bosses, rescued any hostages or defeated the mastermind, Colonel Vermon CaTaffy.

I hadn’t given my failure at this Everest of my childhood much thought until February of this year, when the big boss’s cartoonish namesake, Moammar Qaddafi, came under risk of defeat at the hands of Solid Snake tens of thousands of Libyan rebels. Qaddafi had fallen off my radar. As a child of the 80s, Libya had reigned in my mind as a source of villains – the West Berlin disco bombing, the Pan Am 103 attack, their communist ties to the U.S.S.R., and their assassination of Emmett “Doc” Brown. As the Cold War faded, however, I stopped worrying. I grew to take State Department pronunciations of “enemy countries” and “Axes of Evil” with some degree of cynicism.

So, oddly enough, did the video games I played.

Home video gaming started to come into its own in the mid to late 80s. After the E.T. fiasco wrecked Atari, Nintendo and the NES console stepped up and took over the home market. The demand for games was intense. So game after game was churned out, most of them throwing a lone hero against an unceasing army of foes.

Who were the bad guys in these games?

An exhaustive list of every NES game produced between 1985 and 1995 is more effort than I can put in on a deadline (unless some of those volunteers who helped Belinkie out with his L&O database want to pitch in). But most military shoot-em-ups featured uniformed bad guys, square-jawed heroes and simple, patriotic themes. The enemy countries were rarely made explicit, but you never needed details. They’re the bad guys, you’re the good guys – go get ‘em!

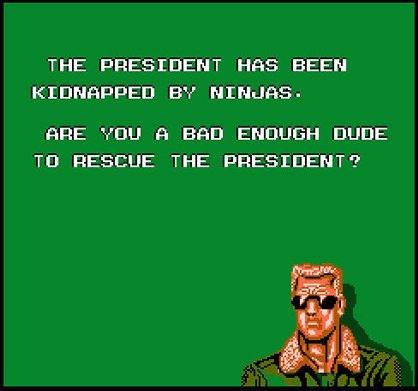

Of course, any detail on who exactly the bad guys were usually came from the instruction manual. If you slapped the cartridge into the console and hit Power, you’d usually get a slow-scrolling text box and then a quick shove into the action. Consider the opening “cinematic” for Bionic Commando.

Or for Metal Gear.

Or for Jackal.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svGkctaM43w

Or for Rush’n Attack.

Or for Rolling Thunder (just to break the Konami kick a little):

You get the idea.

I don’t know if the current generation of video gamers realizes how recent the notion of Video Games With a Plot is. Sure, second-generation RPGs like Final Fantasy or Dragon Warrior had plots. But those were slow paced games where reading was half the point. Who’s got time to read when the Ikari Warriors need you to lead them through the jungles of … y’know, wherever? Or when armies of ninja terrorists have kidnapped the President? Hit the Power button and start firing!

But now, you can’t even settle into an evening of mindless Locust massacre without sitting through five minutes of cutscenes:

If Gears of War came out twenty-five years ago, it would be Contra. Hell, it was Contra.

But with the growing graphical capabilities of home consoles came a growing emphasis on story associated with gameplay. And as stories grew more cinematic, they grew more complex as well. Even standard military shooters and espionage action/adventure games started to take on deeper plots, more fleshed-out characters and a more theatrical feel.

And the biggest turning point was Metal Gear Solid.

Metal Gear Solid for the PSX was the most successful action platformer to incorporate cutscenes. While Japanese RPGs had made use of them for years (Final Fantasy 7 breaking a lot of ground), they had never been used in an action game as effectively as in MGS. Plot details, mission assignments and clues for how to proceed were all revealed through 3D rendered graphics. They looked clunky, even at the time, but moved with a fluidity that was closer to real than we’d ever come.

Why did MGS in particular need so many cutscenes? Because Hideo Kojima had a story to tell.

He’d had a story to tell with the original Metal Gear as well, but American audiences missed out on it. In the original version for the Japanese MSX2 home computer, the final boss was not Colonel Vermon CaTaffy but the military commander who sent you on the mission – “Big Boss” himself! What a twist! Unfortunately, the home video game console Famicom and the NES got an unauthorized port, changing up some of the gameplay and the villainous mastermind.

So video gamers got a straightforward story in 1988 with the original NES Metal Gear and a highly complex story in 1998 with the PSX Metal Gear Solid. But in the intervening ten years, the story didn’t just change. It also grew a lot more cynical.

To sum up briefly (deep breath):

In Metal Gear Solid, Solid Snake is dispatched to nuclear weapons facility Shadow Moses deep in Alaska, which has been seized by terrorists. However, in the process of sneaking through the facility, Snake learns that (1) a Metal Gear walking tank is being housed at the facility; (2) the terrorists are former members of an American special forces unit, codenamed FOXHOUND; (3) Snake has been infected with a virus that’s tailored to kill only members of FOXHOUND, (4) so that the U.S. Gov’t can get its hands on the Metal Gear tank, (5) which is piloted by Liquid Snake, Solid Snake’s twin brother, (6) both of whom are clones of military commander “Big Boss” (remember him?).

And that’s considered one of the simpler plots in the franchise.

But this isn’t just about the Metal Gear franchise. This is about the evolution of video games as a storytelling medium. And it’s also about Libya.

1988: simple stories, like the original Metal Gear or Bionic Commando. The gameplay itself was complex, with players wandering between levels at their leisure, but the story had no twists to it.

1998: complex stories. Now the plot will twist at least once before we get to the end. Friends become enemies (Rainbow Six) and enemies become family (Metal Gear Solid).

Can the stories get any more complex? What happens in the late 00s: 2008, 2009, 2010?

The video game that inspired this survey, a game I recently completed, was 2010’s Just Cause 2. It’s a compelling 3rd person shooter that blends the sandbox play of Grand Theft Auto with the high-energy stunts of Bionic Commando. It’s set in a richly rendered tropical paradise. The game features a variety of play styles and mission types, all challenging and satisfying.

But what’s the story?

Wow.

To recap: the “Agency” (read: the CIA) sends in one of its top hitmen and saboteurs to destabilize a foreign government. Why? Because the last President was a willing pawn of the U.S. and the new one isn’t.

While the game doesn’t make explicit the U.S.’s interest in Panau until the final mission, it’s not hard to deduce. Especially as the game starts rewarding you for blowing up oil rigs. And petroleum depots. And oil pipelines. As special agent Rico Rodriguez, you can advance the storyline by either causing random chaos or by aiding the cause of a local warlord – a Communist demagogue, a radical Islamist or a crime boss. At the end of the game, you’ll have to pick one of these to be the next ruler of Panau, after you get done murdering the old one.

I consider myself pretty cynical when it comes to global politics. But I couldn’t write a game this gritty and expect it to sell. You play a CIA agent who invades a foreign country, topples the current President and replaces him with a new one who’ll be more friendly to the oil-hungry powers. Forget all notions of liberty, justice or peace – that’s as mercenary a view of geopolitics as one could hope to find. And it’s in one of the most popular video games of 2010.

Playing Just Cause 2 while the news is full of stories about Western special agents intervening in the Libyan rebellion is a little bracing.

(JC2 walks back a little from its cynicism in the final chapter, but that’s almost an afterthought)

And Just Cause 2 isn’t alone in this. Consider Grand Theft Auto 4 and the rest of the series, in which you play a rising druglord pitting inner-city gangs against each other. Or how about Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2, in which the American intelligence community allows a Special Forces soldier to participate in the massacre of civilians at a Moscow airport?

Rescuing the President from ninjas, this ain’t.

They never explained why normal succession procedures broke down, did they?

So what’s changed in the last twenty years?

For one, graphical rendering capabilities have grown more sophisticated. The miniature movies that bridge the levels of play are no longer just cartoon heads and scrolling text accompanied by a teletype noise. They’re now full-motion video, or animation so rich that it almost passes for reality. With these tools at your disposal, you can communicate a more layered message. The mission briefing is no longer limited to 255 characters.

But that’s not quite enough. Having a more movie-like medium at your disposal doesn’t guarantee a more complex message. As evidence, I submit the corpus of Michael Bay.

For another, the line between “action” and “role-playing” has been blurred. Video game RPGs have always had complex plots. Plots were their chief feature – if they didn’t have plot, all they had was a different palette of enemy sprites and a new name for the “Healing” spell. So you had the Dragonlord offering you the chance to rule at his side in Dragon Quest, or Golbez’s true identity in Final Fantasy IV, long before action games offered any twists in their linear story.

But that’s not quite enough, either. There’s a difference between being betrayed by one’s former masters – a plot common to many stories involving ninja, government assassins or super cyborgs – and serving one’s masters faithfully to accomplish a questionable end. One’s a recognizable tale of redemption. The other leaves you asking whether it’s worth it to get up in the morning.

My theory (and I’m only partly satisfied with this) is that this is a natural evolution of the medium. When a new storytelling outlet emerges, the first stories will always be the common ones – the Hero’s Journey, the Community Triumphing over Adversity, Boy Meets Girl, etc. The next generation of storytellers will stretch their wings, trying more complex tales. And the next generation after that will be the ones to turn the gaze inward, using metafiction to question the validity of storytelling rhetoric itself.

Film is a good example, one of the few new media that’s unfolded in recent memory. The very first films were straightforward stories, from the simple narrative of The Great Train Robbery to the light but intricate hijinks of The Philadelphia Story. Later generations used movies not just as another voice for culture, but as a means to question the existing cultural narrative. Consider The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, or In The Heat of the Night. By the late Sixties and Seventies, movies were now rewriting the narrative format in order to tell stories that challenged our conceptions (Easy Rider, Dog Day Afternoon, Apocalypse Now).

The process of using movies to challenge an audience seems natural to us now. But it took at least three generations to get to the point where it was common. Plenty of movies were preachy before that point. But the language of film itself – editing, pacing, cinematography, soundtrack – wasn’t used to confuse the notions of Hero and Villain until the movie business was good and established.

Perhaps the video game industry, now more profitable than Hollywood, has reached that same point. Maybe the stories available to a video game have evolved from simple beat-em-ups – you’re the good guy, there’s the bad guy, kill kill kill – to introspective journeys. Maybe the third generation of video game designers has looked back at the last two and said, “Yes, but what else is there?”

As the villains of my childhood – Qaddafi, Mubarrak – give way to the politics of new generations, I started reconsidering the games of my childhood as well. Is Just Cause 2 a response to Rush’n Attack? Is Grand Theft Auto a commentary on the urban warfare of Bad Dudes? Are we not just supposed to beat these villains, but question whether the Hero/Villain label fits anymore?

Maybe. I’m guessing here. I’m honestly not 100% satisfied with this answer. If you have a better notion for why video game plots are more complex, cynical and meta-fictive than ever before, sound off in the comments. And tell me which games you’re playing, too. I’m always looking for something challenging, and I don’t just mean the boss battles.

Cool article, I’m just playing through Just Cause 2 right now… and it is an immensely cathartic game… but clearly now I’m going to be disconcerted by it. I thought the first one was more about Cold War era interventionism, since the country was Cuba-y, and leaders were deliberately taken out for being too pro-Communist as I recall.

John,

Don’t be silly. The Lockerbie plane was destroyed by the US and Iran jointly to give Iran its one and one only revenege fot IR655

Charles Norrie

The American version of the original Metal Gear kept Big Boss as the final villain. It was only the instruction manual that talked about CaTaffy.

Just picked up a used copy of Mirror’s Edge on PS3. Always looked interesting, but never got around to it. It’s really interesting and definitely challenging. It forces you to think differently than any other game I’ve ever played.

Great article. Two comments:

1. Contrasting games with a heavy plot and games that dump you immediately into the action: there’s something to be said for games like Link to the Past that dump you into the action, and then reveal the loads of plot details once you’re invested. I love the fact that the Final Fantasy 4 opening narration doesn’t show up until you’ve already been walking around for a while.

2. Rico sounds exactly like Triumph, the Insult Comic Dog. “That’s a bitter pill, Kane. (For me to poop on.)”

Rico sounds exactly like Triumph, the Insult Comic Dog.

… damn it, yes. Well, that’s stuck in my head now.

I agree with the natural evolution of narrative complexity theory, but I wonder what shape the introspection would have taken had it not been for Columbine being blamed on Doom and then the Bush era paranoia. The whole “faithfully serving a master to a questionable end” bit I don’t think would have been such a potent storyline. But, maybe for people in Libya it would have, if they play video games? Maybe if they did the protests would have been more violent? JK, kinda.

If military violence and imagery wasn’t so much a part of our lives and urban anxiety wasn’t a problem, there probably wouldn’t be such cathartic attraction in more realistically told FPS. It probably would have stayed within a more comic zone, which is probably why it took so long for a Duke Nukem sequel, which looks like an Iraq war allegory. Or just stayed within a Tom Clancy sort of patriotism, with one or two rebels defying the mold.

There was a podcast on technologies role in the Mideast uprisings, and this guy said that in the Eastern block it actually stalled revolution because people were distracted and comforted by tv and such. But I don’t know what in America we would rebel against, we seem to have this Rebel Without a Cause mentality that doesn’t ever really to rebel that much or change anything.

There were a couple games that commented on the First Gulf War and the Colombian civil war in much earlier days: Desert and Jungle Strike. The first had a Saddam analogue acquiring and using WMDs and the latter had co-operation between a drug lord and a nuclear terrorist… but it was certainly far from as narratively ambiguous.

I say play Heavy Rain. That was the best movie-like game I’ve played. Some parts were corny, sure. But, it was epically good at everything else.

The thing that disappoints me about a lot of these military and international plots in action games recently is that it always seems like the writers have very limited knowledge of history, political science and international relations. I’m an international security studies major and I laughed and hit my forehead so many times while playing the latest Metal Gear. The plot is just stupid.

Queet, what’s the most accurate game so far, and do you think it’s possible to make a fully accurate one that’s still fun to the average player?

I notice that this apparent passage through cultural-narrative stages seems to be happening more with games focused closer to our home time and world rather than far future or ancient settings. My perspective is limited by my small gameworld I play but I haven’t noticed greater cynicism or meta-fictive elements in fantasy games like Bioware’s fantasy and scifi games or Halo, whereas I 100% agree with you when it comes to Ubisoft’s Tom Clancy games. If I am right in this, then I think the trend you are picking up on reflects widespread ambivalences about our particular contemporary world. If you consider action films set in the here and now cynical or angst-ridden anti-heroes are entirely the norm – Clint Eastwood, modern Mel Gibson, Christian Bale, modern Robert Downey Jr, etc. In historical films this moral cynicism is not found – Russell Crowe, medieval Mel Gibson, Victorian Robert Downey Jr. When being a cynical morally troubled anti-hero is the norm is it so surprising that cynical morally troubled anti-heroes “side with the great against the powerless”?

2 Kinds of moral difficulty, both fitting within the person vs self conflict to varying extents.

1) The protagonist is morally uncertain about themselves – their badassness is a function of their interior a) morale apathy or resignation (Sam Fisher, pre-enlightened Neo), or alternatively, b) moral ambivalence (Zuko, Batman on killing).

2) The protagonist is uncertain about the morality of a course of action under consideration but not particularly doubtful of their own intentions (Ang, King Arthur, Batman on turning himself in). Not considered badass no more.

This is a false dichotomy but, even so, the first is clearly a tendency in contemporary-set storytelling. Of course there are also character what have no moral difficulties at all, like enlightened Neo and Bruce Willis and Denzel Washington characters. I tend to think that the second kind of morale difficulty is a more common and persistent challenge in life.

I’m not sure we waited as long as the seventies to get films which used the medium introspectively. What about something like Sunset Boulevard?

Also, how do pure adventure games, such as Monkey Island (1990), Maniac Mansion (1987), or (going back even further) the Infocom series of text based adventures fit into your paradigm? They certainly had plots.

That’s a good point. But although there are always going to be exceptions, but I do think it’s fair to say that generally, there’s more meta-filmic shenanigans and moral ambiguity in 70s cinema than there is in classical Hollywood cinema. (By the same token, the claim that literature got more crazy and self-referential in the 20th century is not disproven by the existence of Tristram Shandy.) As for adventure games, I’d say they are like RPGs: defined by the presence of a plot from an early stage. (But the plots for Zork and the Colossal Cave Adventure are pretty elemental compared to later games like Space Quest!) Perich seems to be talking pretty specifically about action games, which are a different animal. And action games really have gotten plottier.

There are some interesting exceptions here too, though: River City Ransom, for its time, is almost absurdly plot-heavy, and includes an RPG stat-building element. And you could make similar arguments for Castlevania 2, Zelda 2, and – ooh, especially this one! – Strider.

I’m not much of a video gamer, so maybe this doesn’t fit, but I do know that I have turned to video games as a release for the anger and frustration I feel about something in my real life. I consider it the mental equivalent of going at a punching bag. Yet even in less morally-fraught games like World of Warcraft, there has been a turning to this type of moral ambiguity. In Wrath of the Lich King,t here was a quest where you had to torture someone. In Cataclysm, there are several quests, now with a bit more variety of choice, but with the option of torture. I hadn’t really thought about why.

In some ways, I think you’re right in that it’s a maturation of video games as a storytelling medium. As graphics improve, the makers of the games are (perhaps unconsciously) more likely to imbue the characters with personality. Which makes them more human, and therefore brings in all the complexity and ambivalence that comes with violence against another human being. Instead of a punching bag (or skill tests with the controller), these are real opponents. (For a given value of real.) While we may know on some level that they’ll respawn later, there is still the moment of hesitation and question–should I strike this person who is more like me than unlike me?

Since I’m not familiar with most FPSs, I don’t know whether there are more wave-the-flag kind of games and what their popularity is vs. the more cynical plots. I’d be curious to know, because it’s hard to comment on whether it’s more the game makers or the game players that are driving this. (Both, probably, but I won’t bother commenting just yet.)

An angle that the article doesn’t take into account is that gamers have also matured. It used to be that the target market for video games was young boys (or at least their pocket change). Those young boys (and the more-than-occasional girl) have grown up a lot since the first 8-bit games. They’ve been to college or not, gotten married, or not, and seen a lot more of life than they had when they turned on their first game. They know life isn’t easy, that bad guys can be good guys and the other way around, and that people do bad things for good reasons, and good things for bad reasons. Perhaps the change is as much a reflection of the aging of the gamers as it is the aging of the gaming industry.

Stokes GTA article mentions age influencing game design, how the simplistic morality is an attempt to protect the “innocence” of children. But even if gamers had stopped playing at age 18 I think game story still would have gotten cynical and meta. Look at kids cartoons, there’s a lot of shows with adult level undercurrent. Peanuts talks a lot about depression and has a child working as a psychiatrist like it’s a lemonade stand, that was way over my head when I was a kid, another example, like Stokes mentioned in the GTA article, the Grimm tales. A healthy cynicism is something you want to encourage in kids and isn’t just a reflection of bitterness and disillusion with age, or maybe cynicism is different from skepticism?

I’m reading this article as working from the premise that we’re always living in a cynical time, and that video games can only represent it now due to tech advancement, but when you look at the best selling games for consoles, it shows that racing games are about half of sales-and declining as FPS increase, compare PS2 and Xbox then the next gens. So how is the state of affairs in racing game narratives? If it’s truly an evolution of the medium as a whole then all game narratives should be increasing in narrative complexity and cynicism.