Ahem

But we’re not here to talk about television shows that help adults have active sex lives, we’re talking about Dragon Ball. Take a look at these two scenes, which are loaded with motif and very clearly presented in relation to one another – although they ran on TV a couple of years apart. In each of these scenes, the hero of Dragon Ball, Goku (a powerful kung-fu fighter loosely based on the monkey king of the classic Chinese novel Journey into the West) has been incapacitated, and his son, Gohan, steps up to fight a powerful alien who happens to be a distant blood relation with very nasty intentions.

Gohan vs. Raditz:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MApFNNeZhAk

Gohan vs. Vegeta:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qss9df_bSY

Appropriately enough, I’ve written about repetition in Dragon Ball before — my first post in this series was about it. I’m not bringing them up just to point out the motifs (I’ll quickly define motif as “a meme created on purpose and used for a reason”), but some of them are trickier than others. Coming into his battle, Vegeta’s chest plate has been damaged in a very similar way to how Raditz’s chest plate was damaged in the much earlier fight. Gohan ends the second fight in the same position where his father was in the first fight – incapacitated and about to be finished off. The Demon King Piccolo – one of the series’ early antagonists, is a bystander observing both fights, albeit in different capacities.

But the point here isn’t that these repetitions exist, but that they create a palpable sense for the time that has passed between the two encounters. We see how Gohan has changed, and how he hasn’t. We feel how much he has grown up, and how much growing he still has left to go. The show ran in two heavily serialized parts, from 1986 to 1989 and from 1989 to 1996 (and I’m not including the bastard spin-off that ran from 1996 to 1997), with more than one considerable time skip — characters are born, grow up, and die during the series (and are then brought back to life again, die again and brought back to life again, but that’s not important right now).

The passage of time is important — a lot of the show is essentially about the passage of generations — about youth and age; fathers and sons; wives, husbands and children; vigor, wisdom and the imperatives, and values people ascribe to as they try to live their lives well. There is a lot of ground to cover, so it is important that these events feel like they are occurring over years and decades — they can’t just be suspended in space like a fight between Carrie and Aidan. Plus, since it is fundamentally a comedy in which almost every character is capable of flight, it can’t show the passage of time with the heavy-hearted sighs and creaking joints, like a Victorian parlor drama or a Chekhov play.

Moan of Arc

Dragon Ball uses the bouncing ball to show the passage of the time. It repeats motifs and situations, recalling the same basic relationship people have with the rising and setting sun and the passing of the seasons. Speaking of seasons, like people’s relationship with time, the Dragon Ball model for the passage of time has many small cycles and arcs (the days, hours, months, holidays, etc.), but also has what are called sagas – large, sweeping story arcs, each of which (with a few exceptions) are typically named for a villain attempting to destroy the world or universe or do something else similarly nefarious.

In the early years of Dragon Ball, time is marked by the “Tenka’ichi Budōkai” – alternatively translated as the “Greatest Martial Arts Tournament on Earth” or the “Strongest Under the Heavens Tournament.” One Tenka’ichi Budōkai happens first every five years, then every three years, and we watch Goku grow from a child into a man, periodically competing in this tournament against his various friends and rivals. Each tournament arc is pretty similar – the characters realize who they are going to have to fight in the tournament, there is some sort of major problem they have to solve, but they aren’t strong enough to do it, so they have to train or find some other way to get stronger, all while sometimes searching for the mystically eponymous “dragon balls” that have the power to grant wishes for reasons that become more and more of a formality as the seasons progress. Eventually, all roads lead to the tournament, where rivalries are settled and the fate of the world is decided.

Once Dragon Ball takes its giant leap over the shark and becomes about space aliens (although at this point, rather than splash into the water embarrassed, jumping the shark is where Dragon Ball learns to fly – it then jumps the shark in earnest a few years later), the tournament pretty much stops being the way time is marked, and instead time is marked by the emergence of villains who are deliberately similar to one another – they are similar because the similarity reinforces that time is passing and lets the differences show what that means.

The Sagas

The macro arcs of the major Dragon Ball villains, leaving out some minor ones and others that are important, but don’t get fully realized narrative arcs in the same way the major ones do, are as such:

The Red Ribbon Army – These guys – a combination of martial arts masters and highly trained paramilitary special forces soldiers with advanced technology are bumbling, comedic villains at this part in the series, but they set the pace for how the story arcs are going to be conducted. The Red Ribbon Army has a succession of generals named after colors – General Black is, well, appalling (there are parts of Dragon Ball, especially early Dragon Ball, that are very racist by today’s standards – mostly because of culturally insensitive visual character design. But it’s hard to gauge how much you can really hold a Japanese guy in the late 80s to today’s American cultural sensitivity standards).

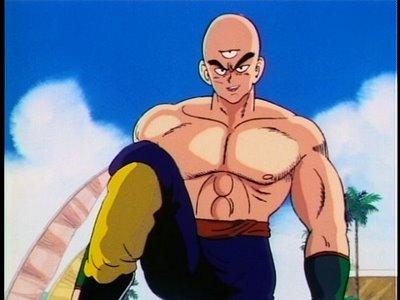

Tenshinhan and the Crane School – This is a rival kung fu school to the protagonists’ “Turtle School.” The Crane School believes in strength, obedience, being ruthless and killing your enemies, while the Turtle School believes in enjoying your life and drawing strength from your desire to have fun. Tenshinhan starts out as a rival but then becomes a close ally after he is bested in battle by the protagonist but spared and encouraged to get stronger. It is a pattern that will repeat.

Demon King Piccolo – This ancient warrior exists in two halves – the good one is the Guardian of the Earth, a peaceful, contemplative dude who lives in a floating island and watches the planet far below, interceding on its behalf with other, more powerful celestial entities. The bad one is a wicked, sadistic monster who at one point ruled the planet below and begins his story arc by escaping from a magical rice cooker. After he is defeated, he is reborn again as a child. That child grows up quickly, becomes the new villain, and then he becomes a close ally after he is bested in battle by the protagonist but spared and encouraged to get stronger. See? The two halves eventually unite again, just for good measure.

Raditz – This is the hero’s long-lost brother, who reveals the hero is actually a space alien, and has come to recruit the hero into a band of cruel genocidal mercenaries. He is killed by the hero and Piccolo, but the hero dies in the process (he gets better).

Vegeta – This is the prince of the alien planet the hero comes from who comes to Earth to avenge Raditz’s death, find and retrieve the hero, and kill everybody on Earth. He takes over from Piccolo as the hero’s main rival through the series. After he is defeated, he becomes a powerful but vain and often unreliable ally after he is bested in battle by the protagonist but spared and encouraged to get stronger. Vegeta is probably the most interesting character in the series for a whole bunch of reasons – he’s the “Over 9,000 guy,” too, but that’s not why I say it.

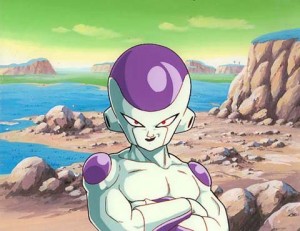

Frieza – This guy is basically the Emperor of the Galaxy. He is a horrible, horrible genocidal tyrant and the Big Bad behind many of the bad things that have happened up until this point in the series. In the end, he loses a kung fu fight (yeah, they don’t solve their problems through negotiation or anything), and he is spared, but he refuses mercy and it looks like he dies anyway. Then it turns out he isn’t dead and comes back as a cyborg, and then he is killed one more time, but that whole return thing is kind of silly and not really part of his saga. Frieza’s saga is the most straightforward beginning-middle-end in Dragonball, and probably the best part of the series when considered on its own.

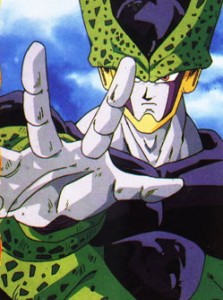

It is amusing that this was in the first page of results in a Google Image Search for the word "Cell."

Cell (and the androids) – Cell is an artificial life form created by the Red Ribbon Army’s remnants based on a combination of genetic material from the heroes and villains of the series. You can add that process to the list of things in fiction that give people super-powers but in real life would probably just give them cancer. There is an initial sort of “half-saga,” in which the heroes fight a series of other powerful androids, but then Cell shows up, absorbs those androids, becomes supremely powerful, and challenges everybody in the world to a martial arts fight, with the intention of exterminating the planet. He is killed, then it turns out he isn’t dead, and then he is killed one more time. Familiar?

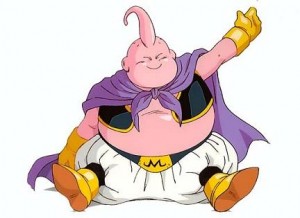

Majin Buu – By the time Buu rolls around, Toriyama is kind of tired of Dragon Ball being so serious and has begun to parody himself, leading to some amazingly bizarre story developments and tonal modulations. Buu is a primordial monster from the ancient history of creation — an enemy and destroyer of the Dragon Ball universe’s original and supreme gods. He is also, at least at first, fat, childish and silly. His plotline is ludicrously complicated and goes on for a very long time in lots of twists and turns until he is killed, but then reincarnated, bested at the Strongest Under the Heavens tournament by the protagonist, made an ally, and taken away to train and be made stronger.

Awesome to see another of these posts!

When you talk about this kind of storytelling having a price, it made me think of console RPGs. They’re nothing if not repetitive. But if they weren’t repetitive, they might in fact be nothing. The charm of that kind of game is often said to lie in watching your character turn into a fearsome badass. Maybe the extreme monotony of the gameplay is necessary for this transformation to feel like biological/psychological “growth” rather than the simple adding up of numbers that it is?

“Maybe the extreme monotony of the gameplay is necessary for this transformation to feel like biological/psychological “growth” rather than the simple adding up of numbers that it is?”

I wouldn’t say “extreme monotony” is necessary, but I think the repetition is definitely necessary. When you think of all the RPGs where you fight “monster” and then later fight “different color of same monster which is stronger” it definitely seems to work that way. If it were always a new monster, it wouldn’t feel like time had passed.

When I saw the title, I assumed this would be about why five minutes on Namek lasts two weeks. Great article as usual and I’m so glad to see both of this site’s resident Anime brains make a return within the same week!

Ha! Yeah, I could write a whole article about the destruction of Namek. The pacing of those episodes is one of the strangest and most agonizing things to have happened on television, and probably most of where DBZ gets its bad reputation.

I always assumed that Frieza just…miscalculated. I mean, he’s a despot who rules through his physical strength. What does he know about cosmology? Unless the implication is that he’s destroyed so many planets that he has some intuition about how long it takes…

The way repetition can show growth and foster emotion between the audience and the work is exactly why Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is so brilliant.

Cool! Proust is a big blind spot for me. I think I’ve brough my copy of _Swann’s Way_ on ten different train trips, but haven’t ever really dug into it. It’s overdue.

If you’re a Proust enthusiast, any translation recommendations?

I’d just like to point out that in the Venn Diagram of “Places where Dragonball Z is discussed” and “Places where Proust is discussed,” the intersection of the two is almost entirely occupied by this article and its comments.

Im so glad Dragon Ball is on OTI. I over thought the powerlevels as a high school kid. Meticulously trying to figure out how much of an energy boost a super sayian gets vs. a super sayian ultra. How is that if a Saiyan gets a 50x boost in power by going super, they can last so long in a fight while normal against an opponent they are equal to as a Super Saiyan.

And one thing I did find out in my own OTI experience was how badly Toriyama messed up in his numerical power ups in the freeza saga. or example, Vegeta was some where between 25,000 and 45,000 when he faced Racoom, but after his power up from healing, he could stand up to Freeza who’s PL was 530,000. Thats a 10 fold increase in power for one ass whooping. By giving Freeza so high a number, he kinda ruined his own DBZ logic in his power ups.

The power levels stop being really consistent around where Piccolo fights Raditz (that is, shortly after they are introduced). Piccolo reveals how you can use your energy in controlled bursts, which lets you fight at a power level higher than what shows up on scouters.

From this point on, I didn’t really see the scouter numbers as definitive. But that’s okay, since it’s a major plot point of the Frieza saga that relying on the scouter numbers is almost always a terrible mistake.

And fenzel I was trying to think of WHY he would even create them in the 1st place. My conclusion is to prove a point. I think he wanted to show that Bad Guys were stagnant, incapable of becoming stronger in means other than completely transforming their bodies while all the good guys grow stronger from training and spiritual growth. Reminds me somewhat of that TMNT article about transformation.

Bingo. The scouters are there for the hubris factor. The elite judge the common people as incapable of rivaling them, which justifies their awful behavior, but turns out to get them in the end, because it is both wrong and unwise.

Even though power levels become massively inflated with the Frieza saga, I still feel they had some sort of significance, apart from showing the bad guys’ dependency on the fixed numbers they get from scouters.

When Raditz appears and we discover that the average human being’s power level is around 5, while Krillin’s and Master Roshi’s are in the hundreds, it gives a sense of all the progress they’ve made since the beginning of the story.

However, the need to precisely measure power levels disappears when Goku becomes a Super Saiyan and completely tips the scale. After that, the characters go back to feeling the power of an approaching enemy. The horrified looks on their faces say at least as much as the scouters ever did.

Finally, thank you someone did notice..

I have no idea what Dragonball is, but I would like to comment on sex and the city… I was watching an episode last week and the girls were at the diner having breakfast, dressed to the nines of course. After breakfast Carrie was going to go buy shoes for their trip to LA that day, and the next scene the girls are arriving poolside at their hotel with the sun high in the sky. Estimate this was at latest a 3pm arrival after a 6 hour flight (and 3 hours back in time zones) so they left NYC at noon. Now anyone in NYC knows those women would have to have left for the airport by 10am for that noon flight. Carrie would have needed approx 1.5 hours to go shoe shopping and get back home to get her bags that puts her leaving the diner at 8:30am. (Saks doesn’t actually open until 10am on weekend so here’s another fault). Continuing on, giving them an hour to eat and socialize puts them arriving at the diner at 7:30am/ leaving their houses around 7:15am. Now for me to personally have been fully dressed, hair blown out and styled, makeup on to the extent they had, I would have needed 1-1.5 hours to get ready. That means according to the “timing” in this episode, they were all up at 6am for this day, whicH I find highly unrealistic considering they are out partying every night at clubs until 2-3am.

And of course, while Samantha, Carrie and Miranda arrive in LA, Charlotte is still finishing her cup of coffee back in the diner in NYC. So that raises the topic of shows that not only have inappropriate passages of time, but have varrying passages of time for each character in the same episode!

I’d also like to point out that the Rugrats are still in diapers and Maggie Simpson still doesn’t know how to walk.

I love this comment!

I love these articles about Dragon Ball and I wanted to say thank you for re-kindling my love of the show. I started watching DBZ during the Namek/Frieza saga when they were airing on Cartoon Network and watched till the end of the Buu saga but once that ended I was done with the show and kind of forgot about it. After you posted this article I went back and read the others and remembered how much I loved the show. I bought the DBZ: Dragon Box One from Amazon and I watched 10 straight episodes last night. I plan on getting the rest of them as well.