AMC’s The Walking Dead capitalizes on the pop culture resurgence of zombies. Though you wouldn’t think it to look at OTI’s back catalog, zombies haven’t always been the most popular horror threat. More to the point, they’ve rarely been very popular. As big as George Romero is in genre circles, his name doesn’t command dollars the way a Spielberg or a Scott might.

But the zeitgeist has brought zombies back around again and, with them, a chance to re-examine the zombie genre.

Though zombies have been present in pop culture since the dawn of the motion picture era, credit goes to Romero for making them a staple. His Living Dead trilogy, which has since expanded into a six-part series, has given us the recognized rules of zombies: their desire for human flesh; their shambling gait; their apparent immortality. It’s also trained us to look for zombies as a means of social commentary.

In many of Romero’s films, such as Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead and Land of the Dead, the message is obvious. Romero has either made it clear or the film lays it on pretty thick. In remakes of Romero’s films (the 2004 Dawn of the Dead, for instance), there’s not as coherent of a theme. And in other zombie films – such as the Resident Evil series – there’s not much of a theme at all.

Of which the less said, the better.

The Walking Dead appears to be a return to classic form, however. The primary focus is on the humans surviving a post-apocalyptic scenario, not the many ways to smash zombie skulls. You could cut and paste any end of the world scenario – global warming, pandemic, aliens – and tell the same story. Believe it or not, this is a good thing. Zombies aren’t that rich of a genre trope. They don’t have personality, they don’t have an extensive mythology and they don’t bring out the best in humanity.

In fact, there’s only one unique thing about them.

Of the Romero zombie movies, and of the better zombie stories like The Walking Dead, what elements do they have in common? Let’s consider:

* Night of the Living Dead takes place, primarily, in a farm house.

* Dawn of the Dead takes place in a shopping mall.

* Day of the Dead takes place in a military base outside a small town.

* 28 Days Later depicts our heroes trying to escape London for the countryside.

* Zombieland tells the story of four drifters tooling around the American heartland.

* And while The Walking Dead has spent a large chunk of time in Atlanta, it will, if it follows the direction of the comic, soon be moving on.

What do all these stories have in common? None of them take place in cities.

Modern pop culture conventions have given us the “zombie disease,” some nebulous plague that infects humans and turns them into emotionless sociopaths. This disease is transmitted by a bite, or by fluid contact, and takes effect quickly. This disease also makes them stronger than normal humans, or at the very least resistant to pain. It instills in them a desire to bite other things, and possibly eat them.

A casual knowledge of how disease works makes this seem silly.

(I owe a tip of the hat to my friend Auston H. for inspiring this line of thinking in me. He made a recent series of posts exploring the nature of the zombie disease trope, which I’d link to if they weren’t on Facebook. Get a blog, Auston!)

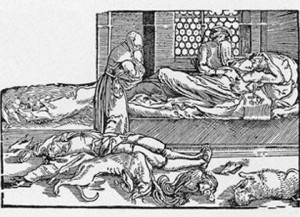

Consider the Black Death of the 14th century, probably one of the deadliest plagues in Western history. This infection was spread by fleas and rats, which carried either bubonic plague or (if you believe some new theories) a variant of anthrax from person to person. The death rate in the cities of Europe was tremendous. The fact that germ theory was centuries in the future and that medieval cities were cesspools by conventional standards didn’t help.

And yet the toll was, at most, sixty percent. That’s nothing to sniff at – seventy-five million dead between Iceland and India. A third of Europe’s population dead inside a few years, with some cities suffering a mortality rate of fifty percent. The instigation of a cycle of plague and whole years, as the disease lingered and took new forms. Yet Europe still functioned. Sort of.

And this was a sickness that spread by fleas. Minuscule little bugs! Could a disease that spread by human contact travel any faster?

Clearly, mankind has relied too much on Physick! This is our Folly! Quick, let us Immolate some Jews and restore the Natural Order.

The key to a disease’s fatality – its ability to turn into a pandemic – is its incubation period in the host and its vectors of transmission. In every conventional narrative, zombification has a relatively quick incubation period. A few seconds in some cases (28 Days Later); rarely more than a day or so. Most epidemiologists will tell you that that’s way too fast to be effective. The bubonic plague doesn’t show symptoms until two to five days after exposure. That’s plenty of time for the victim to wander around, casually infecting his friends. That’s what makes it so deadly.

Further, a disease which can only be transmitted through fluid exchange – or through a bite – can definitely be controlled. The reason that HIV hasn’t decimated the West, despite its insidious power of turning the body’s immune system against itself, is that some simple precautions can dramatically reduce the risks of it spreading. Zombism is similar. It’s not hard to keep someone from biting you.

So zombification doesn’t make biological sense. If this were a conventional blog, I’d smack the dust off my hands and call it a day. But you’re reading Overthinking It. One of the key elements of Overthinking It is taking genre elements as intentional.

Zombification probably could not spread through biting or fluids. So why claim that it does? To make us fear the zombie horde.

Anyone else get really frustrated at this game?

It’s not the lone shambler that we have to worry about. It’s the mass of monsters. It’s a thousand people marching toward us. They can crush us under their dumb weight or rip us apart with their hands. Even if we have a gun, that gun has to run out of bullets some time. And when it does, we’re joining the mob.

This is why so few zombie movies take place in cities. Cities, as the centers of densest population, are likely to be the greatest concentration of zombies. They’ll clog the streets with their numbers. Every person they kill will only swell their ranks. In every good zombie movie of the modern era, the refrain is the same: get out of the city. Get to the countryside. That’s where you’ll be safe.

If you consider this for a few moments, though, it doesn’t make any more sense than our earlier theories on zombie transmission. Sure, cities will be full of zombies. They’ll be packed to the fences. What happens in any hunting ground that’s overpopulated with predators? The predators inevitably die off or move on. You can wait up in your concrete fortress for the hordes to dwindle to nothing, then take to the streets.

“But what about food? You can’t grow food in a city.” Maybe not, but this is true of any place in America. Unless you live on one of the country’s remarkably few family farms, you do not have the capability to grow a sustaining diet. You need to get your food the same place everyone else does – the store. And no one imports more food than cities. Your odds of successful scavenging are much higher in an urban center than in the sparse surroundings.

Everything you need to survive – food, water, medicine, tools, weapons, shelter, clothing – will be easier to find in an American metropolis than outside of a city. Yes, you’re at greater risk of meeting a zombie. But zombies are only one of the things that can kill you in zombified America. Dehydration, tetanus and snakebite are still on that list too.

Good thing we're fifty miles from penicillin!

Again, the point of this exercise isn’t to poke holes in the zombie genre. It’s to strip away the inessentials. People think that zombie stories are about humans doing what it takes to survive. They’re not. Zombie stories are, it turns out, about humans doing what they mistakenly think they need to do to survive. As it turns out, they’re wrong.

But nobody thinks they’re wrong. In Dawn of the Dead, the protagonists take a helicopter and flee the city for a suburban shopping mall. In 28 Days Later, the main characters flee London to follow an intermittent military broadcast. In The Walking Dead, the survivors camp outside Atlanta on an unfortified hilltop, rather than find a secure position.

Survivors just feel safer outside of cities than in them.

I don’t think that I agree with the central hypothesis. In my eyes, two of the central appeals of the zombie genre are the questions: “What happens if we suddenly and unexpectedly lose our intricate network of transportation and communication?” and the related “How would I be able to function in a rudimentary dog-eat-dog society when I don’t even really know how to start a fire, let alone repair the engine of my car?”

Both of these notions have become more pressing in the last decade or so, which in my opinion facilitated the re-rise of the zombie genre more than urban flight: Question no. 1 gains more and more importance in a world in which I can access all the information mankind has gathered in the last few thousand years by the touch of a button, even if I’m walking in the jungle or sitting on the toilet. I can tweet anything to anyone at any time, and some of us might be afraid about that: What if our communication with everyone depends on breakable electronic systems?

The second question relates to the satiric aspects of the zombie genre: The billionaire bank manager, the powerful president and the genius scientist would be nearly worthless in a post-zombie-apocalpyse society. The people we will need are mechanics, the carpenters, the welders. The average nurse will be more helpful than the average doctor, which means that paygrades will be reversed. And this reversal is especially attractive to an audience that is displeased with said bankers and presidents, celebrities and what-have-you. The phenomenon of cities being unattractive locations during a zombie attack is IMHO included into this reversal: NYC, for example, would be reversed from being the cultural and financial capital of Western society to a lonely and fearsome place nobody wants to go to.

Now, the following point touches on a different subject, but since you mentioned it: I usually hate it if something in a story doesn’t make inherent sense or is insufficiently explained. The one big exception is the zombie virus: Even the strong attempt at explaining the background and the mechanics of the disease is detrimental to a key aspect of the zombie genre: The notion that civilization is overrun by a catastrophe that can not be foreseen, stopped or explained. In serious zombie movies, none of the characters has ever seen a zombie movie before (in fact, they often don’t even know the word), which enhances the feeling the apocalypse could not have been expected in any way. This is also the thing which makes the zombie genre different from (and more attractive than?) “usual” disaster stories: In the usual earthquake, climate change or meteor movie, you have this one guy who knows in advance what’s going to happen and trying to warn everyone. In a zombie movie, this same guy might not even know anything is happening while the outbreak is already going on, because he’s in a coma or something.

Anyway, that’s just my two cents. Please tell me you find it interesting, otherwise I just wasted precious office time.

Time spent commenting at Overthinking It is never wasted!

I don’t think your theory and mine contradict. The useful people in a zombie apocalypse are the social outcasts (that guy in the hills who hunts with a crossbow) and the lower classes (that Honduran who speaks no English but knows how to strip down and service a Ford). The useless people are the middle and upper classes – the kind of folks who fled to the suburbs. So maybe we’re touching on the same story from different facets.

Yenzo, this is definitely an interesting take on post-apocalyptic narratives as a whole. (So you’ve earned your paycheck today as far as I’m concerned.) But if that’s all that’s going on, what would separate the zombie movie from the Mad Maxes and Waterworlds?

Thanks a lot for your support, guys! In that case, I will write some more ;-)

@John: Yes, we might be on to the same thing. I guess it’s a question of which effect explains how much variance in the zombie genre.

@stokes: You’re right, I was basically only talking about disaster stories, not apocalypse stories like Mad Max etc. There is certainly a relation between zombie apocalypse and apocalypse in general. The main difference between those genres is in my opinion two-fold: first, while a “usual” apocalyptic event can certainly change the landscape indefinitely, the danger itself is usually expected to end at some point in time (or it’s already over at the starting point of the story). The one big conflict or the one big flood have ended, and the world is forever changed by it. However, there is no immediate threat left (unless there is a good example which escapes me right now). In the zombie apocalypse, the danger continues indefinitely and might even increase over time (Romero’s zombies have the potential to develop new abilities). This shifts the focus from short-term survival and adaptation to living in constant fear (the effects of which are captured perfectly in the Walking Dead comic books).

The second point is the nature of the threat itself: Every disaster confronts us with our own mortality, but only zombies let us literally look into our own dead eyes, chipped teeth and decaying skin. This is IMO one reason for the constantly high gore-factor inherent in the zombie genre: The frailty of the human body is displayed very openly when someone destroys a zombie body. This concept reaches its climax when someone is forced to fight against a zombie which used to be a loved one just hours or minutes ago: The human ceases to exist and merges with the disaster itself, which is something that no other apocalyptic concept can deliver (unless, maybe, if it’s a religious apocalypse and people have the choice to defect to the side of the demons).

There might even be a third point, but maybe it’s just a subpoint of no. 2: Even if they act like lower animals most of the time, people in a zombie story should never forget that they’re basically dealing with humans in regard to the danger level of the threat: They are equal or superior to us in terms of physical strength and durability, they may be able to climb ladders, use tools and basically clear every obstacle that we can put in their way because: if it was built by a human body, why would another human body not be able to tear it down? The only thing we have on them is technology, and maybe long-term reasoning. If you think about it, zombie invasion stories should be related to alien invasion stories (only that we are the ones with inferior technology etc.), but the usual alien flick doesn’t normally go in this direction. I’m not fluent in sci-fi literature, but maybe there are some interesting storylines to this effect out there.

Everything Yenzo has said is awesome, and correct.

I’d like to offer a few more tweaks. Beyond just reversing the usefulness of high-class/low-class citizens, part of the fascination of a zombie apocalypse is that it removes our status as the Privileged Species: we are just a part of the food chain in a state of nature, and not even the top link anymore. We are busted down to a rank we previously held millennia ago, and it’s exciting to see how that turns out. We haven’t been prey for a long time. It is effective in a negative sense as horror (for obvious reasons) and in a positive way as an opportunity to see how human ingenuity deals with the situation.

Related to that, zombie stories are also Sartre’s moral from No Exit writ large: Hell is Other People. You cannot get away from them. The zombies are inescapable (and are symbolically “people,” whichever group the movie has decided to use them to represent allegorically), and then there are all the assholes you are forced to cooperate and cohabitate with, who are the real focus of all Romero’s movies.

Finally, there is also the true allure of any Post-Apocalyptic story: all social conventions have been removed, or are at least negotiable. This is what plunges us into the state of nature described above, and also what gives the aforementioned assholes more power over you, but it is also very attractive for everyone on at least some level, no matter who you are. It’s a brand new world, Anno Zombi Year One, and while it may not be pretty, you have the potential to make of it whatever you have the power to create.

How blatantly realistic yet beautifully realistic. Win.

Gah, I just realized I meant to say, “beautifully poetic.”

I fail. You win, I fail.

w/r/t science fiction: you know, I think one of the largely unacknowledged precursor texts for the modern zombie canon is John Wyndham’s 1951 book Day of the Triffids. Not so much for Night of the Living Dead, but for everything that came after. You’ve got the slowly shambling flesh eaters, the danger from other survivors, the authoritarian military run amok, and the “continual apocalypse” scenario Yenzo just identified.

Have you purposely omitted ‘Sean Of The Dead’? It takes place in a very big city – London. And Sean is not trying to flee it.

Yeah, Shaun of the Dead is a spoof / reversal of traditional zombie tropes. Spoofs are always tough to examine through the same lens as the ‘serious’ films in a genre.

One point about ‘Shaun of the Dead’ which actually fits in with Perich’s and Yenzo’s comments. Anyone watching this movie would assume that Shaun is living through the Zombie appocolypse but in reality it seems that only London was infected, but because of the lack of transportation and communication, no one in there troupe knew that. Just a small aside.

It fits even better than that–they stay in London, they live through the infection, and, at the end of the movie, they learn how to live with zombieism.

They stay in the city, and they adapt. Urban people utilize each other and survive.

I don’t see “Shaun of the Dead” as a spoof at all. It’s a very traditional zombie movie in basically every way, which just happens to have some romantic comedy elements thrown in. The characters aren’t even particularly genre savvy.

In the original Dawn of the Dead, there was no more explanation than “when there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” It’s an unexplainable, perhaps supernatural phenomenon that has occurred. And by explaining it by not explaining it, the audience can’t seek the holes in the explanations and can concentrate solely on the effects of the menace. Since the advent of the viral cause*, zombie films are less satisfying. Not only are there problems inherent in a pseudo-scientific explanation, the scientists of the world can work on a cure. There’s a hope in that. There’s an out for humanity. And isn’t it dread/lack of hope that keeps us watching zombie films? I think that’s the more basic appeal of the early Romero films: without an ability to explain the reason, there’s no ability to solve the problem. So all solutions are temporary ones. Survive the night. Survive a year. Survive as long as possible, but the dead still walk the earth, and you will never truly win. Isn’t that a bigger fear than our own death? The fear that eventually our entire species is doomed? Survive until our earth dies, our sun dies, our galaxy dies, however far you push it, there’s going to be an end.

* Of course I’m leaving out the Last Man on Earth (from way before the 28 Days Later rebirth) where a plague causes the undead problem, but they’re called vampires, not zombies.

Slightly off-topic, but for a mathematical model of zombie outbreaks, I highly recommend this paper:

http://mysite.science.uottawa.ca/rsmith43/Zombies.pdf

Here’s the abstract:

Zombies are a popular figure in pop culture/entertainment and they are usually

portrayed as being brought about through an outbreak or epidemic. Consequently,

we model a zombie attack, using biological assumptions based on popular zombie

movies. We introduce a basic model for zombie infection, determine equilibria and

their stability, and illustrate the outcome with numerical solutions. We then refine the

model to introduce a latent period of zombification, whereby humans are infected, but

not infectious, before becoming undead. We then modify the model to include the

effects of possible quarantine or a cure. Finally, we examine the impact of regular,

impulsive reductions in the number of zombies and derive conditions under which

eradication can occur. We show that only quick, aggressive attacks can stave off the

doomsday scenario: the collapse of society as zombies overtake us all.

I love this!

“It’s not hard to keep someone from biting you.”

It’s not hard to keep a rational human being from biting you. It’s much harder to keep a rabid biped with opposable thumbs and a desire to do nothing else except bite you, from biting you.

“Unless you live on one of the country’s remarkably few family farms, you do not have the capability to grow a sustaining diet.”

You neglect to consider predation. There are great swaths of America where even if you don’t live on a family farm, you could easily sustain yourself with hunting, fishing, and growing what food you can in your Zombie Victory Garden. And, really, in the event of Zombepocalypse, I wouldn’t think anything about annexing an acre of that corporate farm I live next to.

“Your odds of successful scavenging are much higher in an urban center than in the sparse surroundings.”

I wouldn’t say “much higher,” and any advantage would disappear rapidly due to the much higher population of would-be scavengers. Once the power goes out, you’ve got about a week tops before you run out of fresh food, and then if you haven’t spent all your ammo on zombies, you’re going to be shooting it out over the last of the canned peaches.

Meanwhile, I’m laying out strips of fresh venison to make jerky. It’s a clear win for the ruralites.

It’s not hard to keep a rational human being from biting you. It’s much harder to keep a rabid biped with opposable thumbs and a desire to do nothing else except bite you, from biting you.

Here we stray into the territory of where along the zombie spectrum our hypothetical scenario falls. Are these guys fast, dumb tool-users (like in The Walking Dead)? Are they slow, strong brain eaters (like in the Dead trilogy)? You or I could fend off a shambler with a garden hoe and a quick walk. A sprinter, not so much.

I wouldn’t say “much higher,” and any advantage would disappear rapidly due to the much higher population of would-be scavengers. Once the power goes out, you’ve got about a week tops before you run out of fresh food, and then if you haven’t spent all your ammo on zombies, you’re going to be shooting it out over the last of the canned peaches.

A city that feeds a million people a day will have a greater stockpile of food than a farm that feeds a thousand people a month. Sure, it’s easier to grow more on a farm, but that takes, well, an entire season. Presuming you get it right on the first season. Farming isn’t easy, especially for city boys like me.

Of course there will be a battle with the last survivors over a dwindling pile of resources. I see no scenario where that’s unlikely.

I’m no expert in the Zombie genre, but I will say I found your suggestion that there’s a hole in the epidemiology of Zombie films very intriguing. You mentioned how during the bubonic plague no one knew how it was spread exactly, but we do know people had their own superstitious theories as to how it was spread and how to guard against it. I think it would be really interesting to see a zombie film where the cause of the outbreak wasn’t understood correctly. Maybe something more invisible than a bite or scratch caused it. Maybe there was a longer incubation period. That would be more terrifying–to follow a group of survivors and have one or more suddenly turn without causation.

Also, I do find your second idea regarding city flight intriguing. Isn’t one of the biggest horrors in zombie films discovering that a loved one is infected? That we can recognize ourselves and the people we love within the mindless hoard? I think there’s something there. I think perhaps this was your point, but the suburbs also commercialize the pastoral ideal. If you leave the city, you can escape its moral and political corruption. Life will be simpler, happier. When in fact, there is no escape. The pastoral ideal or myth is something that permeates British literature from as early as the middle ages. Could there be something there in connection with the bubonic plague? Or am I stretching?

The pastoral ideal or myth is something that permeates British literature from as early as the middle ages. Could there be something there in connection with the bubonic plague?

The notion of escaping the city to avoid the Death is definitely prominent in British literature. Hell, not just British – we owe a great deal of Middle Ages and Renaissance tradition to the tales in the Decameron.

I want a zombie apocalypse Decameron. Now.

I only have so many hours in the day!

You know, I bet you could totally sell that idea to a publisher. If PP&Z was published, why wouldn’t a Decameron with zombies make it? I wonder how many of the “problems” could be changed to zombie attacks and the like…

My mind is boggled.

Yeah, Zombie Decameron is a *really* freaking good idea, in a way that P&P&Z never was. Zommb-Decameron? Decazomberon? No no, “Decameron of the Dead.”

@Stokes:

I actually like “Decazomberon” the most- it reminds me of “Necronomicon.” They’d make the movie title “Decameron of the Dead,” for sure- that’d look better on the outsides of movie theaters.

@ Stokes: OMG, and what about a zombified Canterbury Tales?????

(Clearly, I have zombies on the brain right now… I hope they can’t smell it.)

@Perish – first of all LOVE this article! I have a DVDuesday at my apartment every Tuesday and due to yesterdays new releases being ‘The Last Airbender’, my friends and I decided to watch the first three episodes of The Walking Dead (6 of us were caught up, 6 people only saw the premiere and 7 haven’t seen it yet) which lead to lively debates about the Zombie genre as a whole, the specifics of the show and how we would survive the Zombie Apocalypse.

You mention ‘The predators inevitably die off or move on’ . . . my umbrage to this assertion is 1) They are already dead, how do they die off (I don’t mean to sound like a smart aleck when I ask this, I’m being sincere) and 2) They are not smart enough to move on as many of our natural predatory tendencies have been weened out of our genetic code. What I mean by that is if walkers know that through a fortified door is food and since they won’t die of hunger by sitting outside waiting, they would more likely stay and wait then wander away looking for another source of food. (Similar to a dog seeing a bag of food, you put the food in a bowl in another room and they see you put the bag in the pantry. A lot of dogs will spend a few minutes waiting by the pantry before they searching for the food – and yes I’m saying a dog is smarter than Zombie) True, they will eventually move on, but the risk/reward of staying and hoping I have enough food before I have to scavenger for supplies seems a bit too high. Personally, given the option of fortifying myself in a constantly sieged ‘Helm’s Deep’ or stay in someplace where I would only have to fight off a trickle when they do move on, I would take the trickle rather than the faucet.

Also – if ‘World War Z’ taught me anything it would be to go North where the Zombies would freeze. Sorry for all the ramblings – I actually have overthought the genre as a whole and have re-written this many times as I went off on several tangents. :)

Hey Bob!

You mention ‘The predators inevitably die off or move on’ . . . my umbrage to this assertion is 1) They are already dead, how do they die off (I don’t mean to sound like a smart aleck when I ask this, I’m being sincere) and 2) They are not smart enough to move on as many of our natural predatory tendencies have been weened out of our genetic code.

(1) If the zombies were literally immortal, they wouldn’t need to eat. They may no longer feel pain, but the brain – their one weak point – is the hungriest organ in the body. I’m presuming that, while zombies are “undead,” they are not indestructible.

(2) Predatory instinct and “smarts” have nothing to do with each other. This is just law of large numbers – any zombie that doesn’t have the sense to look outside the over-grazed city will starve. Either they get the idea on their own, or the zombies at the periphery of the city-swarm starve last. The effect’s the same.

To address 1, I guess it depends on what type of Z we are talking about. As you mention above – there are several types. Mindless shuffling walkers, sprinters, heck even Romero had a talking/shooting Bud. But in most instances, it seems that the undead have a ‘long’ life cycle (Long considering that they don’t eat).

In 28 Days Later, you can see them still ‘alivish’ but decomposed to a level where they can’t move. Dawn of the Dead remake had them badly decomposed a month or two after the survivors lock themselves in the mall, but still functional. The later of the Dead series (Day, Land, etc) seemed to be months after they last feed, but the walkers still . . . walked.

Rationally – the longer you live the better chance you have to survive simply due to dexterity of the geeks, but when debating a fictional apocalypse, we must define which fictional universe we are talking about ;)

Thanks for writing this, John. The Walking Dead is destined for some serious overthinking, and this is a strong start.

I think you’re dead-on (ha ha!) in your analysis of how zombie stories invariably pass judgment on the suburban lifestyle. But where I think you go too far is your claim that staying in the city is actually your SAFEST option. I’m not buying it.

You say, “What happens in any hunting ground that’s overpopulated with predators? The predators inevitably die off or move on. You can wait up in your concrete fortress for the hordes to dwindle to nothing, then take to the streets.” But in most of the zombie stories I’ve seen, there’s little evidence that the zombies either die off or move on. If they do die off, it’ll be over years, not days. And they aren’t wolves who will trek hundreds of miles in search of food. In a lot of the zombie movies I’ve seen, they pretty much stay in the same place for months, walking in aimless circles, unless they’re given something to chase.

But I think you’re mainly forgetting the first rule of zombie movies – you have just as much to fear from your fellow human beings as you do the zombies. You think you’re just going to able to wander to the bodega down the street and take what you need? That place will be picked clean in hours, and all those cans of Progresso are going to be defended by armed gangs. God help you if you’re a moderately attractive woman.

What I’m saying is, anarchy and panic are just as deadly as the zombies. That’s a big part of the reason you want to get out of the city – the survivors are going to be ripping each other to pieces for whatever resources they can find. You’re better off going to an isolated location, where you can protect yourself against ALL the predators, alive and dead.

Here’s a head start on lines of overthinking:

http://www.cracked.com/article_18683_7-scientific-reasons-zombie-outbreak-would-fail-quickly.html

Hi. First time commenter, long time fan of Overthinking It.

I have been a fan and follower of the zombie genre from the first time I saw Night of the Living Dead when I was maybe 12. For me, our fascination with the “walking dead” derives from the paranoid undercurrent those of us in the developed world have inre: the institutions, infrastructure and community that we are so blessed with yet take entirely for granted. We take things like school and friends and electricity and highways as a given. They’re there today and will still be there tomorrow.

But what if one morning you wake up to discover that your mom has eaten your dad’s head, your phone won’t send or receive Tweets, your school is on fire and there is a pile of smoldering rubble at the end of the driveway? All you have left is your feet and your fists, nunchucks from the flea market, and what food you can scrounge. What now?

At its heart, the zombie genre is about human adaptability. As easy as we have it today, shit can go haywire in a heartbeat. Can we pull it back together and rebuild once the world we know is flipped on its head?

As much as I enjoy the implications and allegories present in the genre, there is a supposition that runs through every traditional (ie. ‘walking dead’) zombie feature that drive me crazy:

Dead Things Can’t Move.

The continued motility of every complex organism on earth (and beyond, likely) is contingent on sufficient hydration and caloric intake. Once the heart stops pumping or sufficient fluids have been drained from the body, cells cease to function and all motility stops. A zombie still needs, at the very least, a pumping heart if it is going to stand up like a good biped and shamble toward its next victim.

No blood pressure = No muscle movement = No zombie plague

And IF cannibalism of living human victims provides enough caloric intake to keep a zombie mobile, it follows that any living humans caught by zombies would be picked clean. Down to the bone. Not bitten and abandoned – as is the M.O. of so many zombies in the Romero-inspired genre.

I’m more primally fearful of the 28 Days Later zombies or the Reavers from Firefly, which aren’t “dead,” just human beings who’ve lost their higher functions and are bent on destroying everything living around them….

Hi Kevin, welcome to the jungle.

Yes, a zombie is a medical impossibility. That’s why I like the zombies in Romero’s movies most of all. In those movies, when someone dies for ANY reason, they become a zombie. If you die of a heart attack in your sleep, you get out of bed a zombie. If you stab someone to death, they’re going to rise a minute later as a zombie.

Instead of trying to come up with a rational explanation for zombies (the disease model) he simply redefines what death means. It’s less “realistic,” but simpler. It dodges the question of HOW zombies work. I think EXPLAINING zombies makes them less scary. So I’m hoping The Walking Dead stays away from, “Hey, maybe we can make a vaccine!” You cannot (in my book) beat a zombie outbreak by using science. Zombies defy science.

@Belinkie, if you or anyone else has read the Walking Dead, do we know if they explain it in the books? I personally, like you, love the fact that they have not tried to explain it and hope it stays that way (Sidebar – if they do explain it, please don’t say how, just that they do as not to spoil anything)

In the comic (where zombies are slow, weak and do not use tools ; they actually stand around for months in front of the prison the characters stay in at some point), they take a long time to work out exactly how zombism work, let alone explain it. As far as I remember, it is not explained in any way whatsoever.

@Bob and VfV: I would say that the explanation in The Walking Dead is pretty much identical to the Romero explanation – in essence, the explanation is that there is _no_ explanation.

I think that is absolutely the magic and horror of the genre, which stories such as Resident Evil miss out on (and as it turns out, Resident Evil is way better as an action game rather than a horror game, anyway, and this is how I tend to try to see all “plague” zombie fiction).

The fact that death itself suddenly and inexplicably changes is _terrifying_ and really adds that disconcerting element of the unknowable (and opposed to simply the unknown). Characters in these stories may make some guesses (hence the “No more room in Hell” approach) but it’s an important facet of the genre, and The Walking Dead, that nothing is ever confirmed.

Also, this “explanation” for the zombies, in my opinion, is really the only way to explain a worldwide zombie outbreak. As this article, Cracked, and many other posters have agreed, it’s a pretty crappy plague when it comes to efficiency, and if it started in one place there’s no chance at all it would go uncontained. However, imagine if EVERY SINGLE DEAD BODY ON THE PLANET simultaneously stood up and started eating people. Instead of a starting population of one infected, we’re facing the entirety of deceased humanity, and their numbers grow quite faster than ours. That’s a totally different (and in my opinion, more interesting) story.

@Christopher – Thank you – that is great! I was afraid they would try to explain it which midichlorian-aways the cool factor.

As long as they follow a consistent set of rules, they cannot defy science. Science is about sussing out a consistent, repeatable set of rules out of nature.

You said the Resident Evil movies are best left out of this, but I can’t help but use them as an extreme example of what you get at on the first page, meaning how the explanations or how the virus spreads simply doesn’t make sense when depicted. I mean, how the heck would the collapse of human civilization cause the collapse of Earth’s ecosystems, too? I’ve only seen the third and fourth once each, but I’m pretty sure there wasn’t really an explanation for why the U.S. became a desert wasteland. And, another beef: Having grown up in Vegas, I’ll tell you right now, sand dunes are NOT POSSIBLE. It’s dirt, not sand. And crappy dirt, at that- you can’t even make good mud pies with it because it’s grainy (a big disappointment for a little kid, as you can guess).

Don’t get me wrong, though- I enjoy those movies. They are fun and pointless, but not good. Which is disappointing, because the video games are genuinely good games.

I’ll also point you to the recent craze on college campuses here in the States and across the pond, Humans vs. Zombies:

http://humansvszombies.org/

I played when I was an undergrad, when it was still really new (I don’t think that website was even up yet- the first year my college did it was ’06). It starts with a starter zombie (called the Original Zombie, or OZ) that looks like a participating human, and while the people they infect must identify as zombies, they have anywhere from twenty-four to forty-eight hours where they are allowed to keep their bandanna in the “human” position. I think an interesting way to mess with it would be allow for an incubation period for every infected human, wherein they start out like the OZ and can infect people that don’t realize the person they’re about to hug is a carrier. That would make it more like the Plague, but I imagine it would also make the game mechanic rather broken…

In traditional spoiled-college-kids-need-something-to-complain-about nature, there was a stink on my campus when some students said it was insensitive to soldiers in and veterans of the current Iraq War. Go figure. >.<

ANYHOO, my point is… well… I kind of lost it. Whoops.

1. I do not have time to read the comments (which are so dense! so numerous!) right now. Frustrating. Promise to go back and read asap. Apologize in advice if my other observations have already been made.

2. I Am Legend is sort of a zombie movie set in a city. They don’t call them zombies, but the basic effect appears to be the same.

3. Your observation about Dawn of the Dead reflecting a 1970’s horror of cities reminds me of a movie of the same era: Escape from New York. Manhattan Island has become so debauched, they decided it was easier to wall it off and make it an maximum security prison/penal colony than to clean it up.

4. Zombie Decameron!!! I am so in love with that idea!

I really need to discuss with my LDS friends their perspective on the Zombie Apocalypse. Seems there is an argument to made for Zompocalypse as Rapture variant; just not an instantaneous or pleasant one. Seriously, Mormon families would seem to preemptively have an awfully good position to survive and thrive in this scenario:

One year of food in storage, garden and cannery equipment for more

A home ‘compound’ often in a more rural kind of setting

A familiarity with guns and their upkeep for hunting and defense

An exceptional emphasis on family cohesion and self-reliance

Religious certainty for reunion in the afterlife with family members who are bitten…

I suppose this is a variation on the mountain hermit with a crossbow, or the blind monk with a sharp shovel (from World War Z), but the LDS folks I know manage to engage in middle or upper class lives in society, while also engaging in a survivalist scheme as a hobby.

Me, I’m grabbing my pack and hopping on the first boat to Edinburgh of the Seven Seas.

Oh yay, zombie analysis! There’s been a frustratingly small amount of this considering how much zombies have increased in popularity in the last several years.

There’s an old quote by Clive Barker I love that zombies are the liberal horror, because here are the teeming masses that you’re supposed to want to help but their faces are sliding off and they’re trying to eat the cat. Again, it’s an old quote and may have some validity but it predates the current zombie popularity. I can’t help wonder how much of it has to do with the growing division in the public discourse. There’s been a steadily increasing amount of anger and demonization of the “other side”, much of it stoked by fear. It’s a pretty small leap to “mindless horde of monsters”.

Also, I very much want a Zombie Decameron!

I was wondering how much longer I’d have to wait for The Walking Dead to end up on OTI. I kinda had something in mind that I wanted to submit in the way of a guest article, but I haven’t quite fleshed out yet, and that seems to have a weaker premise with each new episode of the show…

Eli: I know, the successive episodes seem to keep changing the tone of the series, don’t they? You’re still welcome to pitch to us.

@Christopher isn’t this what happens in the original Night of the Living Dead? Some satellite crashes and then the dead rise from their graves. This isn’t an infection scenario at all. The only way living people are turned into zombies is by dying.

@Belinkie you say that a zombie movie is less scary if it’s an infection that could potentially be cured. You may be right, but I think it could potentially be used to great effect as commentary on the violence depicted in these types of movies. Imagine a zombie apocalypse where you know that a cure exists. every zombie you kill to save your own life really is another human being and not merely a shambling corpse. You’d have to think twice about every bullet you shoot. The moral consequences of the heroes blasting through hordes of the undead would be completely reimagined.

@applejack The Night of the Living dead really made no explicit approach at an explanation, IIRC (that satellite thing isn’t ringing any bells at all). I do remember that bites definitely infect and kill in the original movie, based on the fate of the family that stay in the basement with the bitten child…

Also, regarding the cure for becoming a zombie:

This has been discussed in two pieces of fiction I’m aware of (POTENTIAL SPOILERS) – the movie Undead and the Walking Dead graphic novels, albeit only briefly in the latter.

In the Walking Dead books, the characters act pretty much as they have in the show (shooting zombies willy-nilly) until at one point they arrive at a farm. They are shocked and disgusted to learn that the farmer and his children have locked up a ton of zombies in their barn, the zombies being the local townsfolk and some less fortunate family members, ostensibly to await the government’s inevitable cure. In turn, the farmer and his family are WAY MORE shocked and disgusted that our group of survivors have been recklessly killing everyone they know or love or maybe happened to come across on the street instead of trying to, say, help them. It turns into an interesting and thought-provoking conversation until, of course, the zombies break out of the barn less than one issue later and the farmer “learns the error of his ways”, you know, with a hacksaw.

The movie Undead provides a way more interesting example in that (and MAJOR SPOILERS follow, like, I’m about to give the whole movie away, be prepared) there actually IS a cure, and it’s totally effective in a restoring a person to health and sanity. The problem is our main characters have no freaking clue this is going on until the very end of the movie (granted, this might be more understandable than it sounds since the cure in question involved _aliens_ walling in the entire town with an enormous living barricade, levitating all the townsfolk one at a time in no particular order to some random point in the sky for an extended period of time, and literally raining the cure on them all — ….yeah). Regardless of the insane basis for the cure, the fact is that by the end of the movie the only people that aren’t cured are the zombies that were slain during the movie (and, I suppose, some people that were like totally eaten, but that isn’t really discussed). Even MORE interestingly, in a final twist the “final guy”, the one dude who survived it all, ends up still being infected, causing the whole zombie plague to re-explode, this time with no convenient aliens around to cure it. Nice Job Breaking It, Heroes.

@Yerzo The idea of zombies as an active disaster, really makes an important distinction between other apocalyptic genres.

@Perich I think the father and child in 28 Days Later make a strong case for the possibility of long-term survival within a city for precisely the reasons you mentioned; availability of food, defensible shelter, etc. Especially in that zombieverse where the undead begin to decay and cease functioning over time, it seems that the threat could be weathered.

These comments are great, I also really like the idea that the zombies’ bodies reflect our own frailty especially when infecting those previously close to a character. I want to add a question: Do the things in the Crossed comics count as zombies? Though they are not dumb and have an intelligence for creating misery, they share a broad characteristic that would be interesting to define. Maybe a working definition for Zombie: things that transform humans by contact, turning them completely unreasonable and antagonistic to the well-being of others.

‘Unreasonable’ and ‘antagonistic’, I think are key to understanding why zombies are so frightening because both are essential for society to function. That is, afterall the main effect of zombieism: active societal destruction. It’s never that there are reports of zombieism in a far off continent, even impending zombieism; it is always sudden and in the backyard. The Body-snatcher zombies would even work here though they are less frightening because they articulate an alternative to ‘our’ society.