I’m fascinated by songs that manage complexity while admitting to relatively simple and few moving parts, and have on many occasions used this column to point out instances of elegance in the form or design of a work of art.

One such work, which I will highlight today, is “Do You Remember,” which is by about four dozen people, apparently, and represents a massive collaboration, but which appears as a simple, hopeful torch song by Anglo-Indian balladeer Jay Sean, featuring two of my favorite musical forces of the aughts, Li’l Jon and Sean Paul. Observe:

While “Do You Remember” is definitely not as interesting as a self-referential art object as it is sitting at a nexus in the history and business of music, the New Critic in me still prizes the articulation of ambiguity as the source of the normative value of art (over, say, historical prescience, political rightness or expository effectiveness) and the whole media event represented above leaves one very key item tremendously ambiguous:

Do “I” remember what?

Because while the song and video ask “you” if “you” remember, it makes a number of different proposals on different levels about what it is you’re supposed to be remembering. So, do you remember… what?

What?

Yeah!

Okay!

Ah, you begin to see. And if you don’t, don’t worry, because we’ll “bring it back” after the jump…

Do you remember … crunk?

I like to look a few levels in from the get-go on something, which can cause some problems in analysis, I admit, but the first thing I notice in this song is that crunk has officially become nostalgic. For those of you too young or too unlucky to have missed the heyday of crunk, crunk is a style of hip hop from a few years after the turn of the twenty-first century that came from the south — a dance-driven style that cut loose the gangster narrative from the burdens of cogency and steered hip hop back toward a transformative state of material and emotional frenzy.

Like most hip hop, crunk is descended from funk, but while gangster rap dealt with the anxiety of the influence of funk by sampling it — bringing its musical language into a crafted consideration of the historical present — crunk deals with the anxiety of influence of funk by appropriating its goals and metaphysics. It was a compelling step in the divergent but coexisting stories of reafricanization and deafricanization that carried “Race Music” from jazz to GZA.

A word on “Race Music:” It’s important to recognize the racial underpinnings of the way market authorities classify popular music. “Hip Hop” and “R&B” are direct descendants of much more racially pointed terms for what people might perhaps sometimes have the courage to call “black people music.” The music industry has been dancing around its uncomfortable segregationist agenda for a long time now (an agenda that keeps redrawing its lines, but, as we see in this video, seems to see its real hope for integration not with the mass of white people in America, but overseas), but let’s be honest and say that record companies, labels, licensing operations, radio stations, and every other outgrowth or echo of their way of doing business (like Pandora or iTunes) set aside separate space for “white people music” and “black people music” a long time ago, and the distinction stays with us.

“Race music” was the term for it back in the day, then that gradually became “Blues and Rhythm,” which became “Rhythm and Blues,” which has half-rebranded, half-schismed, Tea Party Style, into “R&B” and “Hip Hop.” And while we hardly ever hear the term, “Rhymic Contemporary” is a relatively new genre that participates in these identifications. Even if the audience has become more diverse and the musicians have become more diverse, and the genres have shifted what they represent in practical terms, the dialectic is still there – The Arcade Fire and Young Jeezy occupy separate but equal places on your iTunes playlists.

I mean, do people not get that “urban” is a euphemism? When people say “urban,” they’re not talking about the family of Azeris that runs the cobbler and the barber shop, or the Albanian immigrant landlords. “Urban” ain’t Chinatown, people. I’m not advocating that people conform their musical tastes to the race they “ought” to belong to, and who actually makes and listens to all this stuff is a different conversation altogether, but it’s really silly the lengths people go to to avoid talking about the cultural sphere around black people.

Anyway, “black people music,” from Ray Charles and his predecessors through today’s pop musicians, who practice it more or less regardless of their own race (at this point, the difference is in the marketing), is very concerned with the severance from their traditional culture imposed on black people by slavery. Black people after slavery, kept separate in America from white people by de facto and de jure considerations, faced the problem of how to identify their group’s culture, since, unlike most other people in the world, the history of where they came from and their ties to their homelands were all pretty much obliterated by the forceful breakup of families and the selective breeding of forced labor.

(Hey, sometime this week, take a moment to seriously consider just how bad slavery was. Not enough of us consider that seriously enough. It was really really bad. Holocaust-level bad, except it lasted hundreds of times longer. It’s not even remotely possible that such a massive, long-lived and relatively recent moral and political wound fails to impact all of us seriously each and every day, in America and around the world.)

So, “black people music” comes from a remarkable effort of collective creativity to build something to fill that empty role — an effort that, more than almost any other economic, artistic or ideological project of the United States, has captivated the imaginations of people around the world. And one of the main values behind that effort is an anxiety of interference — that “black people music” is, if you will, FUBU, without a clear pre-established idea of who “U” is and where “U” comes from.

This anxiety of interference lends authority to several different aesthetic approaches to music:

1. Focus on historically black institutions and traditions that were legitimately independent cultural forces even during and after slavery. This is where gospel music comes from. At this point, jazz is probably in this bucket as well.

2. Focus on restoring what was lost through researching Africa and African things. The importance of poly-rhythm and dance come from here, as well as much of the political and cultural discourse around hip hop, and a lot of jazz, too.

3. Focus on personal experience, the artist as auteur, because historical and collective experience sucks. Black people music is full of lone suffering artists who tell the stories of their lives’ suffering, from the blues through Tupac.

4. Focus on making things as weird as possible. Break from the normal, because the normal is lacking. Use robots, lasers, aliens, psychedelia, surreal and disoriented imagery. Break us of our responsibility to a historically informed reality. “Free your mind, and your ass will follow,” if you will.

Different justifications are preeminent e at different times.

I went on this digression because it explains what crunk is. Crunk rode a rising wave of #4, which washed away a previous wave of #3. The self-made warrior poets of rap eventually ran out of cultural energy, and familiarity dulled the edge of experience and became a creative crutch. To break away from that familiarity, a lot of hip-hop in the mid-aughts was deliberately alienating and frenzied, accessing a different level of experiencing music.

This is why crunk artists interrupt the song to yell at you and tell you to get excited about the song you are currently listening to. Two examples of crunk touchstones to refresh your memory or create a new one. Note the distance between crunk discourse and the functional discourse of what we might call “reality” (please follow the link if embedding is disabled):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WVmWKB9xjU

It took a while, but “hip hop” music really isn’t like this anymore. Today’s hip hop makes a lot more sense than this – Jay Z and Alicia Keys don’t see a bunch of police officers with Super Soakers on those TKTS steps at Times Square. And for all the guff Li’l Wayne gets for being crazy and intoxicated, his music is quite descriptive and sensible by comparison.

Compare a crunk video to something like “Whatever You Like” – it matters that T.I. actually has access to a private jet, and that he buys fancy cars and stuff in real life, whereas in an early aughts crunkish video like “Break Ya Neck,” it doesn’t really matter whether Dr. Dre knows where to procure a bulldozer, the training to drive it without injuring himself, or a commercial bulldozing license.

I admit, I’m casting a really wide net here – Busta isn’t really crunk (for one, he’s from New York, not the South). But what is important is the way the vocabulary, visual and verbal, has changed. And it’s changed pretty slowly and gradually — it didn’t really occur to me until “Do You Remember” that Overthinking It has readers who are in college now who might have still been watching children’s television non-nostalgically when “Snap Yo Fingers” came out.

Let’s post “Do You Remember” again, because we’ve wandered far afield on our way home:

None of the suggestions for the what that we’re supposed to remember (Is it us, or is it the woman so vaguely referred to in the lyrics? I think it’s mostly us, the audience, being asked to remember lost love as much as all the other cultural elements.) are hit all that hard. This isn’t a full-on crunk song or crunk video. But Lil Jon is there doing his thing, calling on us to get excited – asking us to remember how things were when Crunk was King, a time which, for many people, due to age, economy — and cognitive dissonance if nothing else — was a better time than today.

It’s the remembrance of somebody older and wiser. We can “bring it back” … and conjure its memory. But we’re not so much recreating crunk as bringing back the positive feelings of it and what they meant to us. Note that the video is of an out-of-context party scene with an indistinct sequence of events where a whole bunch of rap producers are hanging out with random people for no reason — it’s somewhat crunkish.

As a further note on crunk, check out my Bling Bubble article – a piece of OTI nostalgia in its own right.

Google it, and marvel that I published this article a year before similar articles were published both the International Journal of Communication and the New York Times. Professor Christopher Holmes Smith better recognize!!

YEAH!!! OKAY!! WHAT?!!

Do you remember … wearing clothes?

The second thing that really strikes me about this video is how… dressed everybody is. Katy Perry is getting thrown off Sesame Street for showing her breasts sans nipples to Elmo nowadays, but this isn’t a new phenomenon. Being close to naked has a proud tradition in videos.

The clothes everybody is wearing, which seem pretty humble and not that fancy, are themselves nostalgic. This is a party of the sort many people many people may remember from childhood – people just hanging around outside without anything too outrageous going on — no crazy gold or diamonds, really (well, nothing that isn’t incidental). The biggest, fanciest, most ostentatious object is the ultimate humble urban entertainment — a spraying fire hydrant. And nobody even gets wet t-shirted on it.

Do you remember … that multi-ethnic guy named Sean?

There’s not too much to say about Sean Paul’s appearance in this song except that it’s really sweet. I love Sean Paul when he’s just being nice to women he really likes, asking them to have fun, reminding them they are attractive even if they are older and married and he isn’t really interested in them. Sean Paul doesn’t get enough credit for being the Admirable Shaggy — a crossover artist who didn’t pander to the stereotypes of the exotic. Yeah, his videos could be raunchy, but a song like “Get Busy” is mostly just about really being attracted to women and enjoying their company.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cy8eIhenr0w

One of the cool things about Sean Paul’s presence here is as an antecedent to Jay Sean, both because of the name and because of the international and ethnic diversity in “black people music” that they represent. Sean Paul is part Jewish, part Chinese, part English, and part Afro-Carribean, and Jay Sean is a native-born Brit with Indian ancestry.

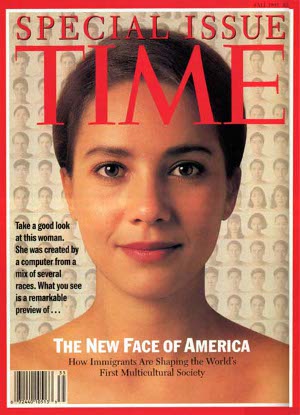

Back in college, my friends and I (not my OTI friends; I had other friends, as hard as that is to believe) used to talk a lot about “The New Face of America,” which is a reference to a specific issue of Time Magazine from when we were much younger but was kicking around the culture at the time:

My friends and I were mostly talking about the attractive mixed-race and multi-ethnic celebrity women of the time, like Jessica Alba or Kristin Kreuk. But we were also talking about what Bulworth calls “procreative racial deconstruction” (NSFW)

But yeah, Jay Sean, despite not being an attractive woman, is definitely what several of my dearest friends would refer to as “New Face.” I think Sean Paul’s presence in the video is to recall the past and make us a little more comfortable with Jay Sean — showing us the idea that the face of black music, just like the face of America, is changing. That’s also one reason why Jay Sean is shaking hands with Birdman – Birdman does that in videos to lend people credence and respectability, especially among sets who are influenced by the Bloods, Cash Money, and those other associated brands and institutions. It’s a political endorsement.

It’s bizarre that there’s something nostalgic about this, but I think, with the negative energy of the current cultural moment and surging xenophobia, it’s important to remember times in the past when we’ve been excited about making progress. My whole rant on “race music” notwithstanding, there’s something really cool about meaningfully bringing the constructed, alleged races together toward cultural and biological reconciliation.

Also, I like how when Sean Paul shows up in “Do You Remember,” its speaking at a pace and articulation that are easy for most Americans to understand, but, after making his case, he jumps into a brief “Sean Paulish” tear, and then sort of apologizes for it, saying it’s “What He Heard,” and thus from an unreliable narrator. This is in turn interesting because it’s the most specific account in the song of a man and a woman having a relationship — Sean Paul pulls back from the representational by claiming while singing that he heard it from somebody else and is not presenting a firsthand account. Who might he have heard it from? Perhaps himself, five years ago. That’s probably where you heard it from, as well.

Do you remember … the chorus of this song?

“Bring it back” doesn’t just mean restore the nostalgic thing we all really liked. It has a musical meaning, as well. Take, for example, another Lil Jon and Yin Yang Twins collaboration, featuring the top-notch Cuban rapper Pitbull, “Bojangles.” (I probably should offer a blanket warning to not watch a lot of these videos if you’re at work):

This song is nostalgic in its own right (and it’s also not very good), but the main point here is that “bring it back” also refers to “repeat the hook of the song” or “go back to that part of that song that I liked.”

So, if I haven’t adequately made the case that Jay Sean means a lot of things when he says “bring it back,” this is something to remember. Jay Sean says it all sentimental-like, then Lil Jon says it all crunk-like; so of course it means more than one thing at once.

Pop music today is very involved in marketing itself – to the extent that a lot of songs tell you in the song that you need to keep listening to the song you’re currently listening to, going to pains to identify all the artists involved in it in case you weren’t aware of them. So, “Do You Remember” is also about remembering this song. The meta answer is often too easy, but it’s there for the taking.

And, because I like Pitbull and his not-quite-mainstream collaborations with Lil Jon over the past 5 years, here’s a better one that you’ve probably heard before. It’s a bit crunkish, but still fairly sensible relative to an actual crunk song, and it includes a hilarious litany of the Peoples of the Earth that shows how far we’ve gotten since “It’s a Small World After All.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7Lyka8Znes

(Note the endorsing cameo by Fat Joe. The people who learned to collaborate and cross-endorse survived. The “rap game” doesn’t belong to the lone wolf anymore, if it ever did.)

Do you remember … when we were in love?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’ve got to list it, but it’s the most boring aspect of the song. It is kind of funny that so many of the current age’s dominant torch songs are high-energy dance anthems — as if enthusiasm is the answer to every problem — “workin’ it” will set you free.

Do you remember … the economy?

This is the other side of the coin on the humble dress question, and the ultimate source, I believe, of the song’s nostalgia. Ostentation is no longer fitting because the economy is hurting, credit is hurting, people are having a tough time, and that has a direct bearing on romantic relationships.

It’s pretty well-established that, while we like to say the best things in life are free and money can’t buy me love and all that other stuff, high unemployment is correlated to low marriage rates and high divorce rates. The people jacking up the divorce rate in America aren’t free-wheeling, free-spending rich people or socially mobile women ditching their husbands to boost their careers and take their cash — it’s families barely holding it together that can’t exist as institutions without the structural economic support to sustain a common livelihood.

And this is a sad reason why we look for love in the past in this day and age, rather than the present, because that’s where people had greater confidence in the ability of a relationship to have access to the resources it needed to endure the practical challenges of life.

It is ironic, of course, that this looking backward comes from somebody of ethnic Indian ancestry, because the economic ascendancy of developing nations is a big part of the future story of prosperity. But perhaps when talking about “making new memories” while looking back at nostalgia, Jay Sean is talking about consumer demand from the developing nations rebalancing the global economy, providing final demand to make healing the the trade and current account deficits of today’s importers a possibility.

Or maybe not. He doesn’t actually come out and say what he means by it.

ALl this over thinking and yet… he did ask “Do you remember… all the good times we had?” in the chorus, which is the one question not directly address.

True, but that’s part of why I considered it vague. “Good times we had” is part of crunk, part of love, part of a better economy, part of being young and innocent, part of the past artists we like who are featured here.

I just put a sentence in there saying “These are all types of good times.”

So when he asks:

“Do you remember,

do you remember,

do you remember,

All of the times we had?”

He is asking if you remember ALL OF THE TIMES THEY HAD. That includes everything. It has the word “all” right in there. It really does.

See how that works?

Your discussion of crunk made me think of “Family Affair” by Mary J. Blige and its transitory position between genres. Crunk, if I’m reading you correctly, is a form of music moving past the hardship in an attempt to exist outside it. Her song is all about how “getting crunk” does not involve anger, hate, etc., and is simply having a good time. And “get[ing] crunk cuz Mary’s back” speaks to how she and other established artists went with the movement, as well as serves the purpose of reminding the audience who they’re listening to.

Just some internal ramblings, not very concrete, inspired by the above. As per usual, wonderful piece.