Where it all started.

Every epic journey needs its cast of legendary characters: Aeolus, Keeper of the Winds. Calypso the nymph. Scylla and Charybdis. The Cattle of Helios the Sun God. Tieresias, the Blind Prophet. Andy Samberg. Shia LeBoef. The cast of The O.C. The Warner Music Group licensing department.

Wait, what?

In 2005, innovative Grammy-winning British singer/songwriter producer/mixmaster Imogen Heap released the song “Hide and Seek,” a pensive, prog-pop torch song about alienation, nostalgia and the unmet need for love and human connection after a divorce.

Last year, Ms. Heap’s song was liberally sampled (in a virtual collaboration, about on the level of Eminem and Dido’s “Stan” or Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise”) for a hip-hop dance track that hit #1 on the U.S. billboard charts. That song, “Whatcha Say,” launched the solo career of rapper/singer/songwriter/producer/dancer Jason Derulo.

Where it all got "serious."

Lest you scoff, as of this writing, the official video for Jason Derulo’s “Whatcha Say” has more than 75 million views on YouTube – about on par for the official video for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

The song shows signs of staying power with party DJs who have embraced spare few of the current crop of pop artists, putting Derulo in the same post-pop-apocalypse league of perpetual booty shaking (and the accompanying sketchy dark rooms) as Ke$ha and, dare I say it, Lady Gaga.

Along the way, this piece of music went on a strange trip indeed. This is the beginning, the shores of Troy:

And here is Ithaca, far across the wine-dark sea:

This is the home we return to, with its bed made out of a tree and obligatory “name of the guy singing this shouted at the beginning of the song” – why was there a time when people didn’t do that? Somebody remind me in the comments.

And after the jump, Circumspect Mischa Barton weaves a funeral shroud –

Surprise lesson learned: Google image searching Imogen Heap is one of the more fun ways to spend five minutes on the Internet.

The Section in Question

Imogen Heap’s song feels vague and dissociative by design. The song structure is a little loose. The vocoder and mixing carve up the flow and pacing of the language (this is from the heyday of “screwing and chopping” after all, although this song isn’t part of that movement). The images pulled from the singer’s experience aren’t explained in the context of the song, so they evoke a mood before a message. And she doesn’t alter her voice because of an inability to sing, she does it because she’s an artist.

However, some quick glosses reveal the piece as a lot tighter, more coherent and more poetically dense than it might seem at first listen.

The “crop circles on the carpet” and “oily marks appearing on the walls” refer to impressions left when furniture or photographs have been removed from a home after somebody has moved out. The “trains and sewing machines” that pop up are relics of 19th century automation, showing how the speaker feels discarded, old, out-of-body, and less than human. They also refer to the process of making a wedding dress (the “train” is a wedding train, like what a bride would wear, at a wedding, on her clothes and stuff).

“Hide and Seek” is about a woman who has been left behind in an empty house by her adulterous husband who has either divorced her or otherwise declared an irrevocable separation. Through the overwhelming immediacy of the moment, she considers how strange, disillusioned, betrayed, and discarded she feels. As is often the case when people are under stress, she feels outside of her body and questions who she is and what is going on. But the song retains femininity while it dwells on the edge of humanity (thus the vocoder).

The title is really sad – it’s both about the figurative game we all play looking for love and about the literal game we play looking for a friend in a room when you can’t see him or her – and about how you go looking for these people, but they might not be there, or they might be there for a little while and then not be there anymore. The husband isn’t hiding behind the sofa; he’s gone.

(To bring us back into the vortex for a moment, where all modern ideas turn inward on each other and revolve and collapse, hide and seek is a children’s game of “object permanence” – the faculty of trusting something is still there when you can’t see it, which humans are not born with and learn as they grow from babies to toddlers, and then half-unlearn as they become adults. I discussed object permanence in more detail in my Insane Clown Posse series, “Toward a Juggalo Theory of Value.”)

"Whatcha say? That it's all for the best? Of course it is."

Imogen Heap’s setting is a ramshackle, depopulated skeleton of an urban living space, reminiscent of The Waste Land. The speaker is part jilted trip-hop lover, but she’s also part J. F. Sebastian from Blade Runner, the last lonely human left in a nigh-abandoned, still old-fashioned Los Angeles hotel, surrendered to entropy and decay. Much like Sebastian, Ms. Heap goes over to the robot voices for comfort and expression.

The lyrics alternate between describing things from a detached first person perspective and speaking directly to another, unseen character. The part of the song people identify with the most – the catchy part, which has broken off and gone on the aforementioned journey through the popular culture, is spoken by the woman to her absent husband:

Whatcha say,

That you only meant well?

Well of course you did.

Whatcha say,

That it’s all for the best?

Of course it is.

Whatcha say?

That it’s just what we need

You decided this.

Whatcha say?

What did she say?

Here, the speaker is calling out the man as a liar – mocking and refuting the platitudes he offered to ease the point of separation, drawing attention to how little control and respect she has been afforded during the breakup, and denying after the fact the moral high ground and justification that the man claimed as he left her. Then, he’s accusing him of not even having made the decision himself; of being the tool of the woman with whom he cheated.

But the refutation is a bit softened and ironic, as if the woman scorned has come to expect this is the tragic and unfortunate way that human relationships work, and putting in a halfhearted bit of anger at the woman her husband left her for. Relative to how she might be, she’s a bit less angry at the man for being a worthless liar than sad that her life could have worked out in accordance with a different vision, which perhaps belonged to a kinder sort of reality than her own.

To sum the section of the song up, I’d say the message is, “This is the regrettable, tragic way in which our doomed relationship ends.”

It’s also one of the most upbeat, rhythmically and melodically structured parts of the song, because she’s reaching through the mists of her present perspective and scattered memories toward recollections of specific events. This is in itself ironic, that the reality of these things excites her even as they are the lies at the heart of her betrayal, but only really in this context. As you’ll see, future use of this section will put it in very different contexts.

The Orange County

Definite article. Abbreviation.

Hey everybody, The O.C. happened. Isn’t that crazy? Few things make me feel older than The O.C. drifting backward into the annals of memory.

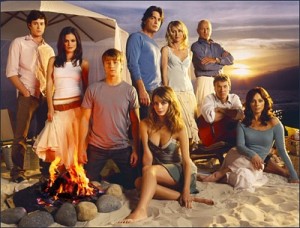

For the uninitiated (and it amazes me that, given some of the ages of OTI readers I’ve encounterd, this might be necessary), The O.C. was a popular for about a yaer and hugely influential long afterward, hour-long TV drama about teenagers and Peter Gallagher that ran for 4 seasons and 92 episodes. In it, a troubled kid from the wrong side of the tracks is Fresh Prince of Bel-Airlifted into a loving adoptive family in fancy-pants Newport, Orange County, California. This kid then has a series of off-again/on-again relationships and engages in social commentary with the various people who appear on the covers of the DVD box sets, especially this one girl who was also in a lot of the other marketing materials.

After its boffo first season on Tuesdays, Fox decided The O.C. was too successful and decided to move it to a time slot of death, where it bled out about half its viewers over its four-year run before being canceled. On Thursday nights, The O.C. competed directly with most of the heaviest hitters of the mid-aughts; Survivor, Will & Grace, CSI, and Grey’s Anatomy were all opposite The O.C. at one point or another. The O.C. was a heavily marketed, professionally written conventional drama with star actors filmed on location on studio territory, so it was pretty expensive – a member of a dominant but waning breed of show. People who watched it more than I did say the show helped along its butchers by deciding after its first season to decline precipitously in quality, but I’ll leave that judgement to posterity and, ahem, people who watched the show.

Even as Mischa Barton and Fox executives leapt from the sinking ship, savvier heads saw how The O.C. had resonated with its target audience and rode its coattails, launching new projects that occupied its cultural space and fixed its problems. They started by lowering its costs, with the reality show Laguna Beach: The Real Orange County and moving on to The Hills. They eventually brought the paired, selfish genes of the glitz of 90210 and the sentimental sincerity of Dawson’s Creek full circle with the consummation and rise of Gossip Girl.

It is bizarre people might not know these things, but, you know what, maybe they don’t. Time does pass, and O.C.s in the rear view mirror may appear closer than they are. The other point of note: despite the way it was mismanaged, The O.C. was popular, high-profile and influential – even when walking wounded, The O.C.’s choices moved the culture.

(ABANDON ALL HOPE, ALL YE WHO ENTER HERE: OC SPOILERS)

The O.C. chose Imogen Heap to underscore a rather sad scene – a funeral for an older character who had a heart attack. This use doesn’t really matter that much, and it isn’t the one everybody remembers. It’s just a random sad song that was kind of current. It’s touching and well-chosen, but unremarkable.

Note that they only use the first part of the song in the funeral intro – the slow, lyrical, dissociated part that nobody remembers and that wasn’t made into a #1 hip hop dance track.For the finale of its second season, The O.C. used the song again, this time the part everybody remembers (and this is a big reason why), this time to underscore one of its most memorable, legendary, melodramatic, and ridiculous scenes:

Okay, what just happened? From what I gather reading summaries during my research for this article, the protagonist is lying on the ground, and the dude who got shot is his older brother, who did not get to have the nice life in Newport that Peter Gallagher gave the protagonist. Instead, the Cain figure, whose name I believe is Trey, descended into crime and drugs. Trey causes problems for everybody all season, and they finally come to a head when the protagonist confronts him during the finale.

Trey tries to shoot the protagonist and, when that doesn’t work, beat him to death with a land-line telephone (not just a land-line phone, but a rotary phone — yeah, The O.C. is getting old), but as you can see, the off-again/on-again girl-next-door character shows up at the last minute and shoots the older brother to death with his own gun. I am under the impression the girl and this guy have an uneasy relationship with romantic subtext and that he tried to sexually assault her at some point, but I’m not sure.

At any rate, there is definitely a big note of “This is the regrettable, tragic way in which our doomed relationship ends.” People are destroyed and left alone (in this case, the ultimate loneliness of being shot in the back and bleeding out on a hotel room carpet) because of hurtful, woeful choices they make. They make these bad choices mostly because they are bad people, but partly because of the unfortunate world they live in. While it is justifiable to hate bad people, it is also common to feel bad about everything that happens and wish it could have all gone better across the board.

This instance has the added layer that, yes, the man is the bad guy here, but the woman is the one enforcing the sexual rejection, the one forcing him out of his familiar world and leaving him alone – literally breaking his heart by shooting it with a handgun that, in turn, shoot bullets. The lines “You decided this” and “What did she say” in particular resonate differently in this context. And in a further irony, despite the huge rift between the brothers that is pushed to perhaps irreparable levels by the one’s attempts to murder the other with a land-line rotary telephone, Trey ends his life lying next to his brother on the floor, in a final tableau of symmetry and shared circumstance.

The song is a bit weird, but it works on several levels – I can see why they went with it. It’s an apt song choice as far as over-the-top underscoring goes, and over-the-top underscoring is characteristic of the genre. Dawson’s Creek did a ton of it; playing a song you want to make popular underneath an important scene, then selling the album or a compilation in connection with the show was a nice business innovation for the teen drama – one of the early moves toward the modern licensing strategy that makes money for shows like The Office. So, it’s good business, it’s good enough art. What’s not to like?

Oh, right. That it’s totally ridiculous. Well, we’re not the only people who thought so.

“The Shooting/Dear Sister”

Andy Samberg and the other folks in the Lonely Island posse, in cooperation with Saturday Night Live, for which they work professionally as comedians and such, did an SNL Digital Short inspired by this specific scene from The O.C. second season finale. (See, the show was very influential!)

It is called “Dear Sister” or “The Shooting,” It’s absurd, it’s awesome, and it has a lot to say about the section of “Hide and Seek” by Imogen Heap that is on its transatlantic, cross-genre Odyssey that ends at the top of the charts. This one also includes the host of the episode, Henry Jones III, Robot-slayer himself, the star of the box office smash hits Eagle Eye and Holes, Shia TheBeef. (This video is an Internet fugitive, for reasons I will explain. This link might not work for long.)

“The Shooting/Dear Sister” first aired on April 14, 2007 (so we’re now two years from when “Hide and Seek” was first released, about halfway to Jason Derulo), and then it ran into a whole bunch of problems.

Imogen Heap isn’t exactly obscure, but she’s also not exactly Taylor Swift, either. SNL had problems getting licensing to use “Hide and Seek” online, probably because of licensing involving Heap, her record company, and people who had previously licensed the song.

So, it didn’t get uploaded in a timely manner to NBC’s Saturday Night Live video website. This is before Hulu was a given, and SNL sketches were routinely posted to YouTube only to be taken down quickly. At the request of Warner Music Group, which I don’t think ever even owned the sole rights to distribute the song, but which had a relationship with YouTube that perhaps YouTube used as cover for a variety of reasons, the sound was muted under any video related to the SNL sketch that did make it on YouTube for a time.

And make it they did! Perhaps encouraged by the lack of online availability of the sketch, perhaps because it was hilarious, a whole bunch of people made their own versions of the SNL Digital Short. They look something like this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JWz0CsvmZ8

Or this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6si7Atk6S0

There are also a lot of them made by teenagers with their own video cameras and fake guns, and while I thought about posting one here, it kind of creeped me out, so I didn’t.

Anyway, two days after the sketch aired, at the very same time that people were making these parody videos of teenagers pretending to shoot their friends, this also happened:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2uECizhheY8

So, the curtain dropped on “Dear Sister.” You won’t find it on Hulu today, and you probably never will. It’s not like it’s impossible to track down, but NBC did everything it could to expunge it from people’s memories, so that nobody remembered that they were encouraging a whole bunch of children to joke about shooting each other — because there are a lot of the people in the world who are incapable of distinguishing between funny things and serious things.

Speaking of which, enter Jason Derulo.

Admiral On Deck!

The new face of pop/R&B

I shouldn’t bash the guy. He’s quite talented and extremely driven. With a lot of help, he put together a song that I very much enjoy dancing to from time to time. If anything, I’m intimidated by him — while some bright-eyed youngsters get discovered at malls and get thrust into the limelight, Derulo is only 20 and has already been producing records and writing songs for big names like Lil Wayne, Birdman and Puff Daddy (or at least for their record companies) for years. He’s an accomplished dancer who has performed on Broadway (in Smokey Joe’s Cafe, ‘natch). He even has a totally awesome umlaut in his name, which I have been reluctant to use, because it might break the back end of WordPress.

Jason Derülo (there we go) is the next generation of hip hop star — a businessman, a networker, a triple (or quadruple) thread. Gone are the days when you can grab a mike and tell your story from the streets; Derulo as basically been working through a series of paid internships with hip hop royalty, preparing for his big shot.

And for his big shot, somebody made the wise choice of picking an undervalued asset — the “hook” (though it’s really the bridge) from Imogen Heap’s “Hide and Seek,” which had lay fallow for more than two years at this point after being blasted out of the public consciousness by NBC/Universal and Warner Music Group. It already proven to be extremely catchy and capable of going viral, and most of the people who they were going to be marketing it to probably were too young to care very much about its history on The O.C. Even older people don’t tend to remember it that often (thus this article).

That “somebody” who made the wise choice was classical and jazz piano player-turned songwriter and hitmaker J.R. Rotem, the star-farming producer of the Beluga Heights label, who has worked with Rihanna and a bunch of people whose names I am not cool enough to recognize.

J.R. Rotem, his manager Zach, and his brother Tommy. Not sure which one is which, but I think J.R. is in the middle.

An interesting quotation from an interview with J.R. here:

If I hear a song that is already familiar to people and I can flip it, give it a new thing, and move it to a different genre, and in the end just make people happy by entertaining them, then that is what I lead with first.”

With “Whatcha Say,” he definitely “flips it” and “gives it a new thing.” The more I listen to it, the more hilarious I find it. Imogen Heap is all “human relationship are irrecoverably distant and meaningless, and our sins against each other can never truly be healed,” and Derulo is all “But I LOVE you baby!! And I can DANCE!! Take me back, I’ m so sorry; take me back!”

It’s both sad and completely hilarious. Go ahead and watch it again. I know I have:

Remember that the “hook” is a sarcastic mockery of the man’s excuses for leaving the woman in the first place. Remember that these things, even in the context of Derulo’s song, are things he said “Well, I only meant well” – “It’s all for the best.” You don’t generally say these things after cheating on somebody.

And that’s part of the fun — this is a song about young love, which is full of cataclysmic betrayals, desperate apologies, and sweeping and unwise forgivness. Adult love isn’t really like that (sorry, SPOILERS) — and, well, if it is, that’s usually really really bad. So, when Heap is singing these words with stinging alienation, and then J.R. speeds them up a bit, changes the key, and then turns them into some sort of dare to give it all another go, it changes the context completely.

It’s as if begging for forgiveness for cheating is itself a demonstrable act of infatuation, seduction, even devotion that anybody ought to engage in as part of courtship, whether that person has cheated or not. I mean, a lot of these lyrics are just silly and way too on the nose: “I don’t want you to leave me / though you caught me cheating.” It’s bizarre how hopeful and optimistic and dance-partyish a tone the song sounds while being just unfathomably oblivious or insensitive to circumstances. And yet the woman scorned seems to egg him on in embarrassing himself. But I guess that’s what being a teenager is for, and what we respond to when we connect with songs like this.

Yeah, most of Derulo’s lyrics aren’t really doing much, but I love his part of the chorus — it really pulls the song together.

“‘Cause when the roof caved in

And the truth came out

I just didn’t know what to do.

Though, when I become a star,

We can live so large.

I’ll do anything for you.”

Anything, of course, except not cheat on her. I guess we know the answer to that Meat Loaf song (altough it isn’t ambiguous in that song either — he makes it totally clear what he won’t do for love — but that’s another topic for another post.

I guess Derulo plans to not do it again. Of course he doesn’t really express that sentiment. There’s no apology either, really. The whole thing is justified because someday soon Jason Derulo is going to be famous — which, interestingly enough, is the one thing in the world of this song most likely to be true, given his preparation.

And how flippant and yet still glorious is it to say you’ll “do anything for” somebody? Really? Anything ? Anything? I dunno man, judging by all the unjustified “well, at least it wasn’t as bad as” press around the Russell Crowe flick, the age of Kevin Costner Robin Hood is sadly long past.

Well, I defy that! Briefly and out of context! Enjoy!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbgbE2UoZqM

But, to be serious for a moment and once more talking about Jason Derulo, I really really love “But when the roof caved in and the truth came out, I just didn’t know what to do.” This, I think, is the connection between all versions of the song. Wherever it goes, this song speaks to people overwhelmed by the inescapable truth of their actions, whether it’s shooting some random dude or shooting a whole bunch of random dudes for laughs, or having a British divorce.

One of the implications is Derulo’s character is not smart enough to have cheated on this girl out of malice. This would be hogwash if he weren’t supposed to be, what, 16 in the song? He is dancing in a high school in teh video. Maybe at that age I cut him some slack for being stupid, if he shapes up.

And there’s also something really comforting about that stupidity – which is not quite fairly called stupidity. Because it’s not like, in all her age and wisdom, Imogen Heap knows any better how to handle ridiculous adultery and breakup situations.

The roof comes down and the truth comes out, and you just don’t know what to do.

Of course, for some people, you hook up the vocoder and pour out your soul, and for others, you just gotta let it out and dance!

Contrition.

For some reason I feel it’s really important to mention that in that scene from The O.C. Trey didn’t die. After he got shot he was in a coma, or something, and then he was basically fine, and then he left town never to be seen or heard from again.

@lauren

That is amazing. And you’re correct; that is very important.

I guess survivability is higher when you’re dying in slow motion.

This was really fun to read.

So, how would Roger Troutman fit into the chain of transmission? I feel like one of the interesting things about “Hide and Seek” is how it removes the vocoder from its natural habitat. Derülo’s version takes it back home, but instead of being the lead moving over the beat (which is how the vocoder typically works for Zapp – and for that matter how the talkbox works for Peter Frampton, who might be a better touchstone for these songs anyway), it becomes part of the beat that the lead moves over.

@Stokes

Roger Troutman is hidden somewhere in this artice! Can you find him? :-)

Troutman is very much responsible for a lot of what happened to this song; he’s the guy responsible for bringing the sound to Gangsta Rap, most notably through “California Love.” Prior to “California Love,” vocoder was generally associated with experimental music, funk music, sci-fi, and a sort of mainstream music that was immasculine by 90s standards (stuff like Peter Frampton) — in order for vocoder to thrive as a production technique in a business dominated by violence and hypermasculine posturing like the hip hop game of the 90s, it had to be legitimized in a Great Work and endorsed by people whose reputations could afford the risk.

Enter Tupac and Dre, who collaborated with Troutman on the track, giving the vocoder a home in rap music, where it sat comfortably, if a bit exotically, alongside the other tools in the hip hop producer’s toolbox. From there, its creep to dominate hip-hop was slow, gradual but not uninterrupted, and dictated by little more than fashion. But Troutman built its beachhead and legitimized it.

I guess the thing that really pushes vocoder over the top is when the industry just starts autotuning everything anyway. Once you’re already altering every second of every voice, you might as well open the toolbox and use the other stuff at your disposal.

So, yeah, this is more of a cultural narrative than a narrative about musical technique and production, but in the cultural narrative, Troutman fits in because Troutman, Tupac and Dre make “California Love” (which is a huge nexus of musical styles, from Joe Cocker to G-Funk) ten years before any of this happens.

I found him! Now if I could just find that pesky Wizard Whitebeard…

I like the “California Love” connection. But I also wonder if there’s something a little bit irreducible about the vocoder effects in “Hide and Seek.” Most songs where voices are electronically masked like this (whether by Vocoder or Autotune or what-have-you), are futurist. The message conveyed by the technique is something like “We are robots. And that is awesome.” This is true for older songs like most of the Zapp stuff; it is also true for newer songs like T-Pain. The way it functions in “Hide and Seek” is quite a bit different. There’s a sort of masonic sensibility to it, where the central message derives weight and substance from the layers of veiling around it. That is, the song isn’t serious and emotional despite the vocal filters, it’s serious and emotional because of them – the places where the processing threatens to overwhelm the voice entirely are signifiers of spiritual and emotional intensity. “This is so impossible to say, therefore, it must be true,” like.

Between the O.C. and the Zidane headbutt, this has been a fun trip down memory lane.

What do you mean by a “triple (quadruple) thread”?

@Christoph

“thread” should be “threat.” It’s a typo. I wrote a lot of this late at night and we don’t really have editors.

Derulo is a traditional “triple threat” performer in that he has three skills – he can sing, dance and (sort of) rap. But he also writes songs and produces. So the “triple (quadruple)” was meant not so much to accurately reflect the number of skills he has to pointing out that he has a silly lot of skills.

Nice post Fenzel!

I was listening to this song (IH’s original) for the first time in AGES today.

It’s a lovely song. Songs about relationships seem so shallow these days. Every other song on the radio sounds like Jason Derulo’s song – guy/girl did something bad, guy/girl says sorry. News flash people: life’s not like that. You make mistakes; it takes more than sorry to fix them (or it should, at least.) You’d never get away with it in a TV show – why can you get away with it in a song?

Thanks for introducing me to two pretty great songs. The article was brilliant, as usual.

I think another link is that Derulo is like the character in Heap’s song. He hasn’t learned any lessons. He hasn’t altered his personality or behavior and it seems like he doesn’t intend to. He proclaims his name at the beginning (over Imogen’s mockery and criticisms). He says he was wrong and should have treated his significant other better but never implies that he’ll make any significant emotional/behavioral changes. He instead appeals to her sense of some ideal/epic romance in saying “But me and you were meant to last forever” which is impossible (at least in this life). He also seems to think this excuses his behavior. I haven’t quite worked out why if you’re meant to be together you’re allowed to treat your partner badly. Maybe someone can explain that to me. When he says he’ll do anything for her he seems to mean in providing for her, and for things of monetary value. “Give me a chance to really be your man” seems somewhat apologetic but also plays to a sense of stereotypical masculinity.

What really bothers me is that I’m not sure who Imogen is speaking as when her voice is sampled. Is she the girlfriend? The woman he cheated on her with? An narrator outside of the action? It’s made very odd at the end when Derulo starts repeating the end of the lyrics. “Well, of course I did.” “Well, of course it is.” And in asking the girl on the other side of the door “whatcha say”. Is he falling into the trap of being the person Imogen is mocking? Is he transforming the lyrics into something else and giving them new meaning with his earnestness (believe me)? It’s rather confusing. What did he mean well by doing? What’s all for the best?

I do like how at the end of the video she’s going to open the door but we don’t see what happens so while she might be taking him back she could also be ordering him out of her doorway.

he makes it totally clear what he won’t do for love

He does? Will there be an article on that too because I still haven’t figured that one out.

@Igib

I’ll write a post about it at some point, but the short answer is the one thing he won’t do for love is leave her for another woman.

Autotune (which works by adjusting and restricting pitch) is not the same technology as a vocoder.

And while I suppose that trains and sewing machines are relics of “nineteenth century automation”, the lyric in which they’re mentioned is:

Hide and seek

trains and sewing machines

all those years

they were here first

This, and the whole song, makes a lot more sense if you interpret trains and sewing machines as toys (cleverly sex-suggesting), “they” as children, and the relationship having ended with the husband taking the kids (which also explains the “ransom notes” mentioned later).

Pete, this was really brilliant. Thanks for it.

This was a meme I totally loved. My favorite parody was “Dear Persian.”

Knowing the song before seeing the O.C. clip gives it a different context and mentality, at least for me. The second time Imogen sings the “chorus,” the line just before the bridge is actually, “Blood and tears/ They were here first,” a change from the “All those years” in the first time. It makes the selection of the song all that more fitting, if the lyrics are actually somewhat under-thought, even if that specific lyric isn’t heard. Blood and tears show up, but not first- yet they are totally anticipated, and a mental back-track clicks into place; and the lyric can be transposed quite nicely, too, because the blood and initial tears come before the questions of what happened in the shooting. He had to get shot, and she had to cry, before anyone could say it was all for the best.

And I definitely dig the parallel of Derulo and Odysseus. The former’s song is the latter’s tree/bed.