Today, enjoy this post from guest writer Trevor Seigler. —Ed.

The Sorrows of Young Charles

In modern literature and film, there exists the concept of the “anti-hero,” a figure upon whom greatness is not so much thrust as it stampedes over the poor fellow, leaving him with little option but to rise to the occasion. It is within his failings as a conventional hero that we as the audience find our connection with him, a “just like us” quality that either helps elevate him to the heights of heroism (Han Solo) or sends him screaming off in the other direction entirely (Yossarian). Many figures, both great and small (and small-minded) make up the panoply of “anti-hero,” and it’s a long and distinguished list. If a particular list is missing a certain bald-headed young boy who loses more often then he wins and lusts after an elusive red-headed girl, however, it cannot said to be complete.

Charlie Brown is one of the unlikeliest of figures around which to center your artistic endeavors, yet Charles Schulz chose to do just that over the course of almost fifty years. Beginning in October of 1950 and ending one day after Schulz’s death in early 2000, the comic strip “Peanuts” revolutionized not just comic strips in terms of what they did, but also in what they said. Much of the biographical work done on the creator of this strip centers on how his theological impulses colored the strip in moralistic overtones that might make some of the strips seem a little passé in our more modern and jaded times. But I think that to dismiss “Peanuts” as merely a dogmatically religious artwork that doesn’t address the real issues of young children is a mistake, especially when you discount the possible existential influence of the main character.

Now, existentialism is one of those fancy-sounding phrases that are thrown around a lot by people who went to college who tend not to really know what it means, but like to sound like they do. That would include people like me. I’ve never delved into the fundamental text concerning existentialism, Sartre’s “Being and Nothingness,” but I’m guessing not a lot of people reading this article have either, unless you just want to torture yourself. But the basics of existentialism, as I understand them from “The Stranger” and listening to Joy Division, are that a.) there is nothing beyond this life, and therefore no rules such as those laid down by religion really apply because let’s face it, there is no reward or punishment for our behavior, and b.) you’re free to do as you please, which can be a great thing or a harrowing version of Hell in its own right, depending on who you ask. It’s the “get out of jail” card of modern philosophy, a double-edged freedom that might actually enslave you more when you think about it.

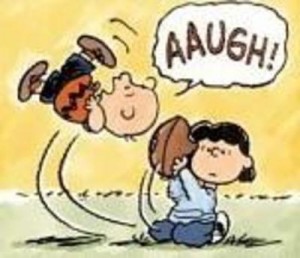

In “Peanuts,” we have the template for an existential hero (or anti-hero) established with the framework of one Charles “Charlie” Brown, whose hapless blundering through life reflects less the course of an apostle for Christ than the progression of Mersault from one meaningless experience to the next, except that Brown isn’t lucky enough to be guillotined in the end. He has to get up out of bed every morning and go through the same hell, over and over again. Lucy will always pull the ball back right before he goes to kick it (the textbook definition of insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” certainly applies here). He will always pitch his way to a losing season, with the occasional run hit his way knocking him off the mound and stripping him of his clothes in the process. He will always be at the mercy of his more imaginative friend Linus, whose boundless optimism is tempered by his reliance on his security blanket to get through the day. Indeed, if not for Linus, one could argue that Charlie Brown doesn’t really have friends or meaningful relationships. He is alone, standing on a beach not with a gun in his hand but with a pitcher’s glove, at the whim of an uncaring or nonexistent deity as he stumbles through life. For Charlie, hell truly is other people.

In “Peanuts,” we have the template for an existential hero (or anti-hero) established with the framework of one Charles “Charlie” Brown, whose hapless blundering through life reflects less the course of an apostle for Christ than the progression of Mersault from one meaningless experience to the next, except that Brown isn’t lucky enough to be guillotined in the end. He has to get up out of bed every morning and go through the same hell, over and over again. Lucy will always pull the ball back right before he goes to kick it (the textbook definition of insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” certainly applies here). He will always pitch his way to a losing season, with the occasional run hit his way knocking him off the mound and stripping him of his clothes in the process. He will always be at the mercy of his more imaginative friend Linus, whose boundless optimism is tempered by his reliance on his security blanket to get through the day. Indeed, if not for Linus, one could argue that Charlie Brown doesn’t really have friends or meaningful relationships. He is alone, standing on a beach not with a gun in his hand but with a pitcher’s glove, at the whim of an uncaring or nonexistent deity as he stumbles through life. For Charlie, hell truly is other people.

Charles Schulz, at least according the biography “Schulz and Peanuts,” wasn’t too much more cheerful than his singular creation, a fact that raised eyebrows upon the book’s publication some years back. The only child of a barber and a homemaker, “Sparky” grew up in the Minnesota of the Great Depression, where times were tough. Schulz didn’t make friends easily, and a sense of loneliness pervades each “Peanuts” product made for mass consumption over the years. Yes, Charlie Brown has friends, but he is unique in that his is the barometer by which the other characters can compare their own lives favorably. It’s no accident that Charlie continually makes the mistake of turning to Lucy when he needs counseling, he really has no one else to confide in. Much like going for the ball when Lucy sets it down, however, Charlie sets himself up merely to fail, as his usual diagnosis seems to be “chronic blockhead syndrome.”

Without delving too much into the potential darkness in Charles Schulz’s life, then, I’d like to try and get at the root of what makes Charlie Brown so much more than some superficial mouthpiece for Christian piety (as those who are critics of Schulz might suggest). Charles Brown, to paraphrase “A Few Good Men,” stands on the line separating us from mediocrity even as we use him as a punchline when we’re at cocktail parties.

There But for the Grace of Snoopy Go I

All creative art comes not from a place of happiness, or at least not too much art of any lasting worth. This isn’t to say that all creative geniuses are miserable Goth kids, just that a lot of them have to go through some sort of emotional turmoil in order to perfect their craft. For Charles Schulz, the death of his mother followed by the isolation of basic training and service during the closing years of WWII gave gravitas to his desire to be a comic strip artist, and it’s interesting that “Peanuts” characters never really grow up but also rarely have a parental figure around (except in the form of the ridiculously-voiced teachers in the animated specials). The sense of failure and rejection that colors every interaction Charlie has with his peers comes from Schulz’s own insecurity, and anxiety is a powerful motivator for artistic creation because it is fueled by self-doubt and feelings of unworthiness unless one produces something of lasting value.

In the very first of the “Peanuts” strips, we are introduced to Charlie Brown memorably: two kids (a boy and a girl) are sitting on the curb of a street when the boy notices a confidant-looking child walking their way. He tells us this is Charlie Brown, yessir, good ole Charlie Brown, and you begin to think that this is yet another character whose dimensions are more heroic than a normal child’s would be. Charlie Brown, so far, seems to be the most popular guy in his world, and he just saunters on by with a wide smile on his face as his peers talk him up. It’s only in the last frame that we realize what’s really going on: the little boy who was saying what a great fellow Charlie is ends with the punchline “how I hate him!”

In that one moment, we know everything we need to not just about Charlie but about the world around him, the world of children who, in the case of the anonymous hater, look down upon him either because he inspires their wrath or because, more frequently with Lucy and anyone not named “Linus,” Charlie Brown is a figure of ridicule and a good figure by which to measure yourself, because you always come off looking better. It’s as powerful a staantement of a creator’s intent as any that I can think of in the postwar world, an exercise in black comedy that predates Vonnegut by a decade at least.

Charlie Brown suffers in almost every strip devoted to his exploits ever since (in order for “Peanuts” to survive, Schulz had to occasionally focus on another character, such as Lucy, Linus, Schroeder, or Charlie’s sister Sally, in order to keep from running low on ideas). He is not the master of his world so much as its pawn, and the relentless assaults on his dignity and self-worth suggest a Kafkaesque existence where the forces of some nameless bureaucracy have aligned against him almost at birth. His cry of anguish, “augh!,” is his only way to voice his frustration, and Linus serves as his source of inspiration to keep the last panel of any strip from being a silhouette of a bald-headed kid with a noose around his neck or a shotgun in his mouth. To get perfectly blasphemous about it, Charlie Brown suffers for us, so that we won’t have to. If he wins, we lose as readers. What if Wile Coyote actually catches the Roadrunner, or the Trix Rabbit finally gets to eat the cereal that lies at the heart of his gnawing need? We lose interest in their pain, and so it goes with Charlie Brown.

The World War I Ace vs. Camus

If Charlie Brown is not always the star of his own life story, he has a great co-star to pick up the slack. Snoopy the Dog is my favorite anthropomorphic character because he inhabits a world most of us can only hope to glimpse, where pure imagination is let loose and no restrictions are in place to prevent his doghouse/Sopwith Camel from being riddled with bullets. Charlie and Snoopy, far from being totally different, are actually complimentary, because Snoopy is the positive expression of “no rules” in existentialism that Charlie represents on the negative side. For every blunder and missed opportunity for Charlie, his dog can transcend the dullest of postwar suburban conventions and experience a full and rich fantasy life that his owner can only look on with wonder and regret. Snoopy might make for a better existential hero, in that he is bound to no one save Charlie and Woodstock, and really even then it’s only by the slimmest of threads. Snoopy, however, chooses to be Charlie’s constant pick-me-up, leading his pals in dance and constantly one-upping Lucy by kissing her. If Charlie Brown can’t stand up to what the world throws at him, Snoopy will; it’s no coincidence that the first “Peanuts” book was entitled “Happiness Is a Warm Puppy.”

Good Grief

“A Charlie Brown Christmas,” the 1965 animated film that established the “Peanuts” characters in popular culture as more than one-dimensional figures, could be said to “cop out” on the overriding statement made by the strip to that point. Charlie Brown, of course, cannot win, nor can he have the satisfaction of knowing that he’s right even if he’s outnumbered; the minute he becomes less neurotic, he loses his everyman quality. “Christmas,” on the other hand, not only rewards Charlie’s effort to find a home for the small, pathetic-looking Christmas tree, it also validates Linus’s position as the voice of reason in a sermon that would ring patently false if it were handled without the dexterity of someone well-versed in the pain as well as the pleasure of life.

With all that being said, is it necessarily a bad thing for Charlie to get one in the win column? Life would be unbearable for anyone if they were not granted the occasional high point, and Charlie Brown would end the film despondent if Linus didn’t intervene. Charlie’s real-life counterpart in pop culture, Woody Allen, occasionally gets the girl, even if he doesn’t know how to handle it. For Charlie, the acceptance of his tree signals the acceptance of his humanity into the community that hitherto has mocked it or bruised it with repeated pulls on the football just before it is within his reach. The pain and agony of Charlie’s existence isn’t just because he can’t throw a strike or talk to the little red-headed girl; its roots lie in the absence of a sense of self-worth, as he is not validated by those whose approval he seeks.

In life, you learn more from your failures than from your successes, even if you keep trying to kick that damn football. It’s the abiding faith that someday, somehow, you will connect and make that kick that keeps you going, no matter how often you fall down. Perhaps it’s fair to ask what is the point, but to do that would negate Charlie Brown not just as a figure for sorrow and pity but also as a human being (albeit one who has been preserved in amber as a child with male-pattern baldness and an unyielding wardrobe of yellow-and-brown shirts and oversized baseball caps). Charlie Brown is us, he embodies the parts of us that we’re not proud of, but they’re essential to any understanding of ourselves.

In life, you learn more from your failures than from your successes, even if you keep trying to kick that damn football. It’s the abiding faith that someday, somehow, you will connect and make that kick that keeps you going, no matter how often you fall down. Perhaps it’s fair to ask what is the point, but to do that would negate Charlie Brown not just as a figure for sorrow and pity but also as a human being (albeit one who has been preserved in amber as a child with male-pattern baldness and an unyielding wardrobe of yellow-and-brown shirts and oversized baseball caps). Charlie Brown is us, he embodies the parts of us that we’re not proud of, but they’re essential to any understanding of ourselves.

Is Charlie Brown a Christian martyr, then, who “dies” in a sense so that we might live? Or is he an existential figure of shame and scorn, a Mersault or the lead character in any Godard film, whose greatest crime against humanity is simply that he exists and continues to do so in spite of our repeated efforts to negate his worth? I think the answer lies somewhere in the middle and it depends on your perspective. To me, he’s the literary character I identify with the most, and I’m guessing by the continued popularity of “Peanuts” in all incarnations that I’m not alone. He’s Gatsby, Holden Caulfield, and every character Woody Allen has ever played, and he’s never going away so long as lonely boys look out the window at a game going on across the street and wonder why they weren’t invited. Charlie Brown might not smoke thick French cigarettes and rail against the bourgeoisie, but he’s just as existential as Camus and Sartre. You might not agree with me, but I’m guessing you’ll find it harder to look at a “Peanuts” strip again without feeling a little more in touch with Charlie’s hell. Art that makes you feel as well as think has an infinite shelf life, and “Peanuts” might just outlast us all.

I wonder if a better actor analogue Charlie Brown might be Larry David, especially in terms of the football gag.