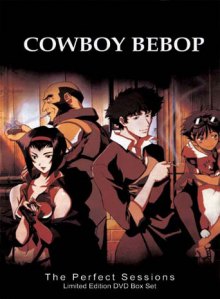

Stokes’ Grand Unified Theory of Cowboy Bebop

Old Junk?

As we learned from “Speak Like a Child,” obsolete technology in Cowboy Bebop is a stand in for the series itself, or more specifically for the genres, cliches, story devices, and other cultural detritus that the writers used to cobble together the narrative (which in turn makes obsessive-compulsive technology geeks like Doohan and Miles into something like author avatars). It’s very interesting, then, that this episode has the characters constantly destroying the technology they fetishize. The little golf-tee looking thing is only useful to Spike in that it’s broken, and therefore sharp enough to scratch glass. Spike kicks his ship’s computer apart to fend off the carjackers’ virus. When Doohan shows up in the Columbia, the Swordfish is out of fuel, so Spike propels it into the docking bay by venting the atmosphere out of his cockpit, and then slows back down again by smashing both its wings off. And from the looks of things, all that work that Doohan’s been putting in on restoring the Columbia (for years and years, mind you!), is going to have to start over again from scratch. Following the allegory through to its logical conclusion, this suggests that Cowboy Bebop, as a show, is primarily concerned with destroying the same old narrative tropes that it references so lovingly.

This had me stumped for a while, I’ll admit. I mean, it’s not that strange of an idea in itself… It’s pretty easy to read a movie like High Plains Drifter (where – spoilers! – Clint Eastwood’s iconic “mysterious stranger” character turns out to be an undead rapist) as an attack on the very idea of “The Western,” or to read Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer as an attack on the idea of “The Horror Film.” But I’ve seen some savage deconstructions in my time, and Cowboy Bebop doesn’t feel like a savage deconstruction. For all its peculiarities, it’s still a remarkably joyful show to watch (most of the time), while Henry and High Plains Drifter are worthy but punishing slogs. And while there are other types of narrative that feed off of older stories (parody, pastiche, satire, homage), all of these have their characteristic moods, and Cowboy Bebop doesn’t feel like any of these either. The show’s relationship to its sources is, if not quite unique, at least distinctive and idiosyncratic, and bears some teasing out.

To begin with, Cowboy Bebop requires you to understand the stories and genres that it is riffing off of. Doohan doesn’t get enough screen time to make sense as a character in his own right. You need to bring the Yoda/Hattori Hanzo archetype to the table with you, and use it to fill in the blanks. Same with the sleeping beauty aspect of Faye’s backstory, or the noir aspect of Jet’s, and right on down to the first episode where you know, absolutely know, that Asimov Solensan is going to die in a hail of gunfire as soon as you learn that he’s trying to make one last big score before leaving the underworld for good. Just the fact that we do know these things is not so unusual – what sets Bebop apart is the degree to which we MUST know them in order to get anything out of the show. In most narratives, the writers go for what’s called a “well-made plot,” i.e. one in which all of the actions are coherently linked by causal logic. Mythic undertones (the stuff we bring in through our knowledge of genre, and so on) are like icing, or gravy: surplus meaning that reinforces the meaning already present in the story itself. The plot of Indiana Jones 3 still works if you take all the Sean Connery daddy-issues stuff out of it — it wouldn’t be as compelling, but it would still make sense. Not so for Cowboy Bebop. Here, the undertones are pretty close to the only meaning that’s present. Rather than the icing on the cake, they’re the flying buttress on the gothic cathedral: they may look decorative, but if you take them away the whole edifice comes crashing down. That is to say: you cannot enjoy Cowboy Bebop unless you are conscious of its intertextual references. Okay, that’s a little strong. But at the very least, my own enjoyment of the show – which is what, after all, I’m trying to communicate to you – depends on the knowledge gained through a lifetime of fairly indiscriminate reading and movie watching.

For instance, I'm too distracted by Faye's "sexyness" to actually find her sexy, if that makes any sense.

Unfortunately, knowledge comes with a price. Read enough fairy tales, and you can tarnish the sense of wonder evoked by the fairy tale. Sleeping Beauty is never quite the same once you’ve worked out the sexual subtext. See enough film noir, and the haze of cigarette smoke can no longer represent the moral haze surrounding the characters’ actions: instead it just screams “Hey, Film Noir!” Cowboy Bebop inhabits a textual universe in which narrative has become disenchanted, in Max Weber’s sense of the word. Storytelling devices are present, but we are conscious of them as devices, that is, as tools which we can use to generate a specific effect. We still know they work, but we no longer have faith in them. They no longer enchant us. It is impossible to be surprised when Jet’s old partner betrays him in Black Dog Serenade: the plot device (trusted partner in a noir setting turns out to be playing the protagonist for a chump) has been made instrumental – another of Weber’s terms – meaning that it is subject to our conscious control, but it can no longer influence our subconscious. Contrast this to Star Wars, which relies quite strongly on these old structures still having the capacity to enchant and surprise.

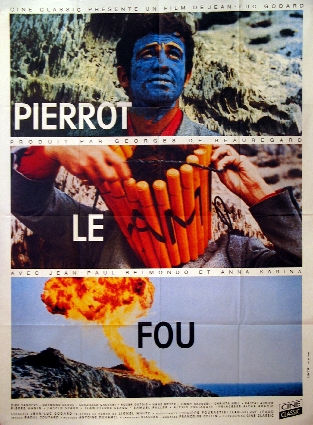

This looks like it most be the most fun movie of all time, right? Yeah... no. Guess again. Oh, and spoiler alert, I guess? Can a film be spoiled by its own poster?

What Cowboy Bebop resembles most closely, in its disenchanted approach to narrative, is the French New Wave. And here I can stop hedging my bets about authorial intention, because New Wave’s influence on Cowboy Bebop is obvious and proudly worn. Dig those bright primary colors! Dig those random intertitles! But if Cowboy Bebop is New Wave, it’s New Wave with the coolness factor turned up to eleven. As important as all those movies are, they too tend to be kind of joyless. In a culture where New Wave cinema is mostly experienced as posters on dorm room walls, this is something I think we tend to forget. We talk about the use of jump cuts, the unmotivated sound effects, the shattered fourth wall, the yé-yé pop soundtracks, but we don’t usually talk about the glacial pace and the desperately unlikable characters. The disenchantment of narrative and cinematic technique in the New Wave is meant to reflect the broader disenchantment of life in 20th century society. The New Wave has no room for zero-g kung fu. It has no room for gleeful, brilliantly choreographed car chases. I’m sure Godard would think that “Mushroom Samba” is just another opiate for the masses… in fact, you could argue that Cowboy Bebop’s attitude is less 1960s New Wave and more 1860s Romanticism. For all that they spent a lot of time swanning about on the moors, the Romantics were actually pretty cynical about life in general. That’s why you had to go swan about on the moors in the first place! Society as a whole was a constrained, depressing, meaningless place – instrumental, in a word – but there were still some things that had a certain enchantment about them, and it was the business of the sensitive soul to seek them out. Calling back to one of my first posts about the show: these fragments of the enchanted are what we in the audience experience as “jouissance.”

It’s important to recognize that what provokes jouissance for the Romantics is not necessarily what provokes it in an episode of Cowboy Bebop. The Romantics didn’t put as much weight on the depiction of unfettered physical motion, and on the other end we aren’t going to see Spike redeemed by the love of a good woman (thank the lord). But it’s interesting that their lists do overlap on a couple of points. One of these is music. And another one is horror. And that leads us very nicely into the next episode, but not today. Before I go, I think I promised you a theory:

(New Wave disenchantment of narrative and filmmaking techniques)+(Romantic belief that the quotidian can be transcended, although not easily)=Cowboy Bebop: a New Wave cinema that’s as stylish and fun as we (i.e. 21st century bourgeois Americans) always imagine the New Wave to be. And furthermore (or “and therefore?”), a New Wave cinema that is almost completely depoliticized. Which is a rather sharp swerve away from the actual New Wave, but maybe I’ll pick that one back up next time.

For all that they spent a lot of time swanning about on the moors, the Romantics were actually pretty cynical about life in general.

Isn’t there a pithy saying out there to the effect that inside every cynic is a failed romantic?

Love this! Excellent work, as usual, Stokes.

Bravissimo, Stokes! I’ve been trying to explain to everyone about how the themes and tropes of the show are essential rather than just background noise, but they don’t get it (and don’t enjoy it either :().

The next few posts will be interesting for sure, Pierrot le Fou, Brain Scratch, and of course The Real Folk Blues are all to come. I wonder what you’ll make of Boogie Woogie Feng Shui as well (since nobody else has seemed to make much of it).

Damn I wish that poster were as exciting as it looks (like Avatar mixed with Explosives: a match made in heaven).

I think the creators recognized that the guys weren’t really Space Pirates, hence the session’s title. They’re Horse Thieves In Space! And as every Cowboy knows, there is absolutely NOTHING COOL about horse thieves.