…Did you think about it? Twenty years. I can see you now, twenty years younger than you are now. You’re sitting on the floor, about an inch from a small, low-definition cathode ray tube. You’re not blinking; you’re holding your breath. Sometimes you feel fear, like when you first realize that Captain Picard—your captain, the captain—has been assimilated by the Borg. Sometimes you feel annoyance; what’s that Shelby girl doing, trying to take Riker’s job? Who does she think she is? She doesn’t have a cool beard!

So sometimes you feel annoyance, and sometimes you feel fear. But, for the most part, your sentiments regarding this episode can be summed up by two words:

“Cool! Robots!”

Then again, I may be projecting. Back when “Best of Both Worlds” first aired in June of 1990, I was six years old. In those halcyon days, I did not over-analyze television the way I do now. Back then, my Overthinking abilities were limited to such genius thoughts as, “Cool! Robots!” “Planets are pretty!” and “I like Data ‘cause he has a cat.”

Things are different now. I’m older. I don’t wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled just yet, but I do pay taxes and take calcium pills daily. And, this week, when I watched “Best of Both Worlds” again, my dominant thought was no longer of the coolness of robots but of what it means to grow up, and what it means to grow old.

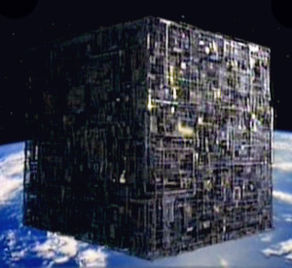

Most people forget that “Best of Both Worlds” has two main plots. The plot everyone remembers is the Borg plot: the Borg come, they take Picard to be their interlocutor, and then they race off to assimilate the Earth. In Part 2, the crew of the Enterprise takes back Picard, and Data hacks into his brain, allowing the Enterprise to blow up the Borg cube and save the Earth.

Few remember the other main plot of this two-part episode: the Riker plot. Or, more specifically, the “Riker has a midlife crisis” plot.

It’s easy to understand why few remember this aspect of the episode. The Borg stuff is action-packed, full of explosions, and very suspenseful. The Riker plot, according to one website I recently visited, seems little more than a “corporate soap opera.”

I’m going to disagree with that statement. To me, the Riker plot is the main story of “Best of Both Worlds,” and the Borg stuff is just fun window-dressing. And it’s not just a soap opera, I’d say. It’s actually a rather subtle parable about the benefits and drawbacks of growing up.

Let me refresh your memory. When “Best of Both Worlds” begins, Lieutenant Commander Shelby, an expert on the Borg, is brought to the Enterprise when it’s discovered that a Federation colony has been destroyed, most likely by the Borg. Shelby has ulterior motives for the trip, though. She’s heard through official channels that Commander Riker has been offered a third commission (this time to captain the U.S.S. Melbourne), and she wants Picard to give her Riker’s job as First Officer.

The problem is that Riker doesn’t want to be a starship captain. He’s happy where he is, and everyone—including Captain Picard—wants to know why. Meanwhile, the ambitious and impetuous Lt. Cmdr. Shelby (who, by the way, is a dead ringer for Uda, Kristen Bell’s character in Party Down) tells Riker, the old fart, to get out of the way and make room for new blood.

Cue Riker’s midlife crisis.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bC7QbuzR-Rk

[The video has embedding disabled, so just click through to play]

In this scene, Riker and Troi set up a dichotomy. On one side is “youth,” represented by Lt. Cmdr. Shelby, who represents Riker’s younger, beardless self. Youth is characterized by ambition and dissatisfaction, an ability to adapt quickly to difficult situations, and a proclivity toward risk-taking. On the other side we have “adulthood,” represented by Riker as he is now. Adulthood is characterized by satisfaction (or complacency, depending on your viewpoint), the wisdom that comes from life experience, and an aversion to risk-taking. Season 3 Riker had been happy being an adult by this definition, but now he’s not so sure. According to Picard and Admiral Hanson, Riker is jeopardizing his career by “standing still” while young upstarts like Shelby fly up the Starfleet ladder at ludicrous speeds.

Riker vs. Shelby

Then the Borg come. This is not a coincidence. Metaphorically-speaking, the Borg represent Lieutenant Commander Shelby and all young upstarts. They are ambitious. They are robotically fixated on an end-goal, yet they are never satisfied enough to end their quests. They adapt frighteningly fast to new changes, technological or otherwise. They take risks because they have no fear.

The Federation, on the flip side, is Riker, and Adulthood. It is a Utopia, and Utopias don’t change much. Why should they? They’re already perfect.

Or so they thought. The Federation brass, like Riker, and like all adults, console themselves with the thought that, while the young upstart Borg have quickness and adaptability and drive, they have wisdom and experience. After all, they’ve already encountered the Borg before. Surely the information gathered in that previous encounter will help them figure out a way to defeat them.

But when the Borg—the always-adapting, never satisfied Borg—rout the fleet at Wolf 359, the Federation quickly realizes that their experience alone cannot beat the Borg’s adaptability, and that the Federation’s complacency and predictability will likely be its downfall.

Part II of the episode finds Riker thrust into the Captain’s chair after Picard is assimilated by the Borg. The main dramatic question, of course, is, “Will Riker save Picard and the Earth?” But since I’ve seen this episode before, I know how that question is answered. So, this time around, my main question was, “How will save Picard and the Earth? How can he possibly do it if his midlife crisis gets in the way? How can this middle-aged adult win a young cyborg’s game?”

We know how he won’t win. At the beginning of Part II, Guinan warns Riker that he cannot rely on his knowledge or life experience, and he can’t play it safe. The Borg have Picard, but, more importantly, they have all of the information in his head, which means Riker’s know-how and experience is useless. “Captain Picard wrote the book on the Enterprise,” Riker says. “If the Borg know everything he knows, it’s time to throw that book away,” Guinan replies.

This conversation, then, seems to tell us how the episode is going to end. Riker is going to throw away his adulthood—his wisdom, his aversion to risk-taking, his knowledge, and his life experience—to beat the Borg. To win, he’s going to have to become Lt. Cmdr. Shelby—revert to his younger self, in other words—and beat the Borg at their own child’s game.

But that’s not actually what happens in the episode. Riker does take some risks: he orders Shelby and Worf to kidnap Locutus/Picard, and he risks Earth to gamble on a risky plan that requires Data to hack into the Borg-net via Locutus’s brain. This plan is so ambitious and unpredictable that Locutus tells Riker that it was the “wrong” strategy. That, of course, was the whole point. Riker has learned to adapt. He has taken part of the Borg’s M.O. and assimilated it into himself.

At the same time, Riker’s plan requires some of his “useless” adult traits, such as wisdom, knowledge, and experience. First, towards the beginning of Part II, Riker makes a point of keeping all of the senior officers in their usual positions instead of making promotions and other changes, because he knows exactly how each of them works. For this mission, Riker implies, the crew’s predictability, far from being a drawback, is a major asset; it allows them to work as a cohesive unit built on mutual trust—which, of course, comes from their years of experience with one another.

Next, Riker decides to use an old plan to trick the Borg. Guinan had warned Riker that he couldn’t use any old plans that Picard already knew about, because the Borg would know them, too. The plan is to separate the two halves of the Enterprise (the saucer and the secondary hull) to create a diversion. Shelby told Picard about this plan back in Part I, so the Borg already know about it, and Riker knows it. So, in part II, Riker uses this information against the Borg. He knows that Picard/Locutus believes Riker will separate the two halves of the Enterprise and attack with the more heavily-armed secondary hull. Riker uses that information to surprise the Borg by attacking with the saucer’s primary hull. This allows Data and Worf to sneak past the Borg sensors in a shuttlecraft and rescue Picard. Contrary to Guinan’s suggestion to throw the book of knowledge and experience away, Riker keeps the book but reads it in a completely different, and unexpected, way.

The final stages of Riker’s plan also rely on his adult traits of wisdom, knowledge, and experience. By using his knowledge of and experience with the Borg, he, Data, and Crusher infer how their computer systems work and how they control the Borg collective. They then use this information to hack into the Borg wi-fi using Locutus’s computer-brain and order the Borg to go into regeneration mode. This then gives Riker the opportunity to “blow up the damn ship.” The Borg cube goes “boom,” Picard is saved, and the Earth lives to see another day.

So, in the end, how did Riker defeat the Borg? He did it by picking and choosing the best parts of his young and middle-aged self. So next time you find yourself thinking about how spunky and ambitious and creative you were twenty years ago and how complacent and risk-averse you are now, take a page from Riker’s book. Be the best parts of your child and adult selves. Then, like Riker, you can be—you guessed it—The Best of Both Worlds.