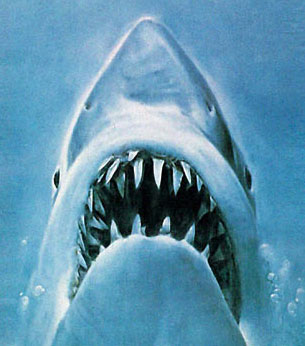

Last month, rtpoe was crowned one of the winners in our Clichemageddon context. As his prize, he got to suggest a topic for a future post. When he mentioned that Jaws is one of his all-time favorite movies, I just couldn’t resist an excuse to watch it again. Richard, this one’s for you.

There’s nothing particularly Overthinky in pointing out how a summer blockbuster is about a regular Joe becoming a real man. Neo flees his boring cubicle, arms himself with a million guns, and sticks it to the forces of conformity. Nerdy Sam Witwicky saves the universe by thrusting his life-giving cube into his enemy’s body. Peter Parker, Bruce Wayne, and the rest of the gang stop being wimpy teenagers and start punching people. Before the 1970s, our leading men were impossible paragons of manliness: suave Carey Grant, steely John Wayne, dashing Errol Flynn. One of the blockbuster’s innovations was that the hero should start out identifiable (maybe even pitiful), and then become Grant, Wayne, and Flynn.

There’s nothing particularly Overthinky in pointing out how a summer blockbuster is about a regular Joe becoming a real man. Neo flees his boring cubicle, arms himself with a million guns, and sticks it to the forces of conformity. Nerdy Sam Witwicky saves the universe by thrusting his life-giving cube into his enemy’s body. Peter Parker, Bruce Wayne, and the rest of the gang stop being wimpy teenagers and start punching people. Before the 1970s, our leading men were impossible paragons of manliness: suave Carey Grant, steely John Wayne, dashing Errol Flynn. One of the blockbuster’s innovations was that the hero should start out identifiable (maybe even pitiful), and then become Grant, Wayne, and Flynn.

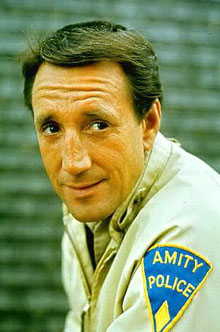

Jaws was a trailblazer here, as in so many things. Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) begins the movie as the epitome of American manhood, almost to the point of cliche. He’s a loving husband, a devoted father, and a solitary lawman protecting his community. When confronted by the shark, however, everything spirals out of control. He watches a little boy get chewed up in front of his eyes, and is publicly berated by the grieving mother. Then the shark strikes again, despite the security measures he puts in place… and this time, his own child is nearly taken. If the first two-thirds of the movie is about anything, it’s revealing the impotence of male stereotypes.

And then something interesting happens. Brody stops being a man and goes back to being a child. He’s taken out of the context of his family and community, and put on the Orca, where he’s completely out of his element. Quint teaches him to tie a knot, which he struggles with (“It’s not too good, is it Chief! Well nothin’s easy is it? One more time.”). Hooper scolds him for bumping the oxygen (“You screw around with these tanks and they’re going to blow up!”). Brody sulks about doing his chores (tossing the chum), and sits awkwardly in the shadows while the “grown-ups” compare scars (they barely remember he’s there).

On the Orca, Brody is utterly useless. But because he is willing to be useless–to regress–he earns himself the chance to become a man again.

The Emperor Has No Bathing Suit

Why must the promiscuous ones always go first?

The movie sets up the theme of male impotence right off the bat, in literal fashion. A group of teenagers sit around a fire on the beach. An attractive blond, Crissie, leads a boy, Cassidy, over the dune. As she runs, she strips off her clothes gracefully and dives nude into the water. However, this isn’t Cassidy’s finest hour. He not only doesn’t score with Crissie, he doesn’t even get his pants off before he passes out in the sand. It’s funny… until suddenly it isn’t. Something attacks Crissie. For an excruciatingly long time, she cries out to the boy for help, and finally disappears beneath the waves. Cassidy stays on the sand and does nothing. It’s a microcosm of the next hour and fifteen minutes. (Bonus impotence: what kind of a boys name is Cassidy?)

We first see Brody waking up next to his wife, with his cute little children barging through the door. It’s a traditional family unit, almost a retro one. Brody wears a gray t-shirt and white boxers in the first shot. This modest sleepwear stands in contrast to the radical dress and sexual promiscuity of the teenagers on the beach. His police uniform is a similarly conservative beige.

The most conservative thing about Brody, however, is his job. He’s not just a policeman, he’s the only policeman for the community (he has a deputy, but the kid is dopey and useless, like all deputies in movies are). You can’t help thinking about the Old West: one sheriff single-handedly holding back anarchy. Mid-way through the movie, Brody explains why he came to Amity:

I’m telling you, the crime rate in New York will kill you. There’s so many problems, you never feel like you’re accomplishing anything. Violence, ripoffs, muggings, kids can’t leave the house, you gotta walk ‘em to school. But in Amity, one man can make a difference. In twenty five years, there’s never been a shooting or murder in this town.

Be gentle with him; it's his first summer.

Brody thinks of himself as John Wayne. “I can do anything,” he tells his wife. “I’m the Chief of Police.” He loves the idea that he, by himself, can keep everyone safe. But almost immediately, the movie starts to poke holes in that self-image. When his child, Michael, enters the movie for the first time, he’s bleeding… and it’s Brody’s fault. “You guys were playing on those swings,” he scolds. “Stay off them, I haven’t fixed them yet!” Much later in the movie, right before he leaves on the Orca, Brody tells his wife: “Don’t use the fireplace in the den because I haven’t fixed the flu yet.” Can this guy fix anything? If the shark doesn’t get his family, carbon monoxide will.

Back in the first Act, Brody walks down the street to buy the materials for his “Beach Closed” signs. We hear a military drumbeat playing in the background, suggesting male determination and vigor. But when he turns the corner, it turns out there’s a marching band nearby (and not a very good one at that). In the general store, he clumsily knocks over a whole jar of paintbrushes. Typing up the report on Crissie’s death, he misspells “Coroner” as “corner.”

These are little details, but Brody also has a huge, symbolic flaw that hints at his impending failure: he’s afraid of water. He’s the Chief of Police of an island that makes most of its money from the beach, but as Bad Hat Harry observes, “We know all about you, Chief. You don’t go in the water at all do ya?” He’s a transplant to the island (a change from Peter Benchley’s novel), and his fear keeps him one step removed from the community he is supposed to be protecting. The first shot he appears in begins with the ocean filling the frame, and then pulls back to reveal the water is safely on the other side of the window. Brody’s job is to keep the people of Amity safe from the shark, but he’s even more afraid of it than they are.

Biting Where It Hurts

He's the Mayor of Fashiontown.

When the mayor confronts Brody early on, he explains that the shark threatens impotence in another way. “Amity is a summer town,” explains Vaughn. “We need summer dollars.” Wage-earning is traditionally the role of the male. The shark threatens to undermine that. Keeping the beaches open preserves the mayor’s masculinity, because businesses will continue to make money. However, it imperils Brody’s masculinity, because it places people in danger. It’s significant that this confrontation takes place on a ferry, where Brody is already nervous because of his fear of the water. In this context, it’s easy to see Brody as a child, bullied and submissive.

In the next scene, Brody sits on the beach nervously, scanning the water. It’s clear that despite his acquiescence to the mayor, he doesn’t believe Crissie died in a boating accident. He’s certainly vigilant; people say hi and he doesn’t even notice them. Yet, the fact that he is fully clothed while everyone else is in swimsuits implies that he’s not really prepared. Worse, he gives permission for his own children to go in the water, despite what he knows.

Then, the Ghost Ship Moment: the raft Alex Kitner is floating on explodes in a geyser of blood. Brody’s reaction is seen in a dolly-zoom camera move, causing the background to seemingly retreat from Brody’s stunned features. This shot has a duel significance. First, having failed as a protector, Brody is in that instant further removed from the community, which literally recoils from him. Second, the shot makes Brody appears to shrink; he becomes smaller than life. (Incidentally, the shot is lifted directly from Hitchcock’s thriller Vertigo, which also deals with a man incapable of protecting his loved ones.)

The speed at which the attack occurs makes a mockery of Brody’s diligence. He is literally right there watching, and he’s still useless. He seems to freeze for a moment, unable to act (reminiscent of Cassidy’s drunken stupor). Finally, Brody runs to the water, screaming for the children to get out, but by the time he springs into action the swimmers are already flocking out anyway. All he succeeds in doing is getting in the way. Despite the chaos, he does not set foot in the water to help anyone.

The ultimate Facebook profile pic.

In the town meeting the follows, Brody could be excused for assuming that the people of Amity would look to him for protection. But his briefing about “shark spotters” is interrupted by business owners with a simple question: “Are you going to close the beaches?” When he says they are, the angry reaction is universal. What the townspeople fear is the economic castration. To them, Brody is the real threat. “Only 24 hours!” the mayor assures them (over the Chief’s objection). So much for John Wayne.

But just as Brody seems to be shrinking into irrelevance, the movie gives us another male figure who seems to have exactly the sort of mythic stature the Chief lacks. Quint silences the crowd with his legendary chalkboard scratch, and then tells them, “Y’all know me.” He’s already a legend, a knight with a castle full of bleached teeth. Quint addresses his speech to “Chief,” but it’s the mayor who answers him, “We’ll take it under advisement.” While Brody seems increasingly out of his element, Quint is confident to the point of nonchalance.

Proper.

This may be a little toooo overthinky (if thats possible) but Brody survives the sinking ship by climbing to the top of a somewhat phallic mast (ascending into manhood?) in order to stave off sinking into the toothed vaginas domain…

Great article. Does this mean when Jaws is remade Brody will be played by Shia LeBeouf?

don’t mind the dicky comment, but i just had to make it: i love my phallic riffles.

You’ve seen “The Ghost and the Darkness,” right? It’s “Jaws” with lions.

there’s some blog that overthinks every Speilberg movie for dozens of pages… can’t find it though

nice article!

Great OTI.

@matt: I hope riffle enters the lexicon for phallic-ness like cod piece.

Another great article – doesn’t seem like overthinkingit at all really – most of this is a pretty convincing reading of the film.

So Jaws is gay?

Great article! And it’s interesting that in “Jaws 2,” Brody had to regain his manhood again, as he spent most of that movie being disbelieved/mocked/ineffectual etc. And he had to do it alone (Hooper couldn’t even come to the phone).

Amusingly, I wrote this paper for a Gender & Sexuality class about four years ago. You’ve got some interesting things here that I didn’t have, and I had a few you don’t, but it’s basically the same paper.

Excellent analysis, very un-pretentious and really interesting. But I take issue with your mention of Cary Grant as some epitome of manliness. While I agree that he is (in many ways), you never mention North by Northwest, which I think is another film about a man who goes from inadequacy to heroism. And if we want to dig deeper into Hitchcock’s oeuvre, The 39 Steps is also similar. Still, really cool essay.

many of hitchcock’s films deal with the hero’s progression towards agency. Especially Rear Window and Spellbound

An interesting article, thank you.

I think an obvious film for the unlikely hero aspect that you mention is “Deliverance” where the man’s man (Burt Reynolds) is injured early on and the pacifist (Jon Voight) has to save the day.

“I think an obvious film for the unlikely hero aspect that you mention is “Deliverance” where the man’s man (Burt Reynolds) is injured early on and the pacifist (Jon Voight) has to save the day.”

Also “The Exorcist,” when veteran exorcist Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) dies and the less-experienced Father Karras (Jason Miller), who’s spent the better part of the movie grappling with his crisis of faith, has to take over and save Regan.

Great article.

I enjoy an article that looks into the symbolism of films, because I am a movie geek and yet have trouble grappling all the metaphors and whatnot.

I particularly enjoy someone writing it out in an easy to read and (as said above) a completely unpretentious style. It doesn’t sound like any of it is made up and it all continues to be interesting.

Cheers.

So is ‘Jaws’ gay? Maybe. It certainly is homoerotic. Apart from all the phallic symbolism is ‘Jaws’, Roy Scheider exudes hot hunky maleness. Take a look at his manspreading in the beach scene in his short pants. He is the epitome of masculine beauty. Also, the scene where he becomes a masculine man to the max aboard the Orca putting on his holster and in tight masculine clothes looking sexy as all hell as he girds his loins for the showdown that of the three men only, he can win. One more thing, so many assume he is afraid of water because of something that maybe happened in his childhood, so his wife says, and he abruptly cuts her off . Not even. He is a Vietnam vet., who either served in the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Coast Guard and volunteered to do so to avoid being drafted into the army. Something happened to him in service wherein he was wounded and nearly drowned. Like many Vets., of the era, he doesn’t want to talk about it. But he didn’t actually serve in direct combat unlike Quint. That is why he doesn’t show his maritime related injury in the Orca’s mess. Notice if he felt that he lost his sense of manhood at sea, he definitely recovers his masculinity at sea. Unlike Quint’s masculine bravado or Hooper’s uncapacious one, Brody’s calibrated masculinity succeeds and wins the day.