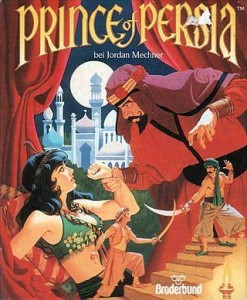

Being not, astonishingly, a suggestion for the world’s best karaoke song, but rather a discussion of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. [WARNING: I spoil the heck out of it. I also get quite a bit more political than is typically “allowed” around these parts. Read on at your own risk.]

There is not necessarily a lot here to overthink. If I was just going to think it, I’d probably say something about how Jake Gyllenhaal is a lot less embarrassing and more believable as an action star than I was expecting. That Gemma Arterton sounds like she’s doing a Katherine Hepburn impression, but it kind of works anyway. That Jeff from Coupling is a good actor, and his chemistry with Gyllenhaal was impressive, but that I could not stop expecting him to start saying “gusset.” That the film, while enjoyable for most of its running time, was overstuffed, littered with plot holes (some of them gaping), and not “good” by most meaningful standards. And that Ben Kingsley needs to take a moment to review the Evil Overlord List, or possibly add to it.

“If I am trying to keep the hero from stealing an incredibly important mystical McGuffin, I will not put it in an otherwise empty room guarded by one nigh-invincible super soldier. Rather, I will have it guarded by one nigh-invincible super soldier and one totally normal dude, whose job is to hide behind the McGuffin’s pedestal, wait for the hero to defeat the super soldier, and then pop out and stab him in the gall bladder when he looks back to make sure the super soldier is dead.”

But in Overthinking It terms, the thing to pay attention to is the heavy handed political subtext. As the film opens, the Persian army is debating whether to invade the holy city Alamut. Intelligence indicates that Alamut has the ability to produce powerful, high-tech weapons (i.e. really nice swords), and plans to sell them to rogue states and terrorist groups. One quick and brutal conquest later, the victorious Persian army marches through the streets of Alamut. Unfortunately, no cache of weapons is found. The Persian King is appalled. We need to find those weapons! Without them, our invasion becomes a war of aggression! We’ll never conquer the people’s hearts and minds! Indeed, later, we learn that the war wasn’t about weapons at all. Rather, it’s about a natural resource, buried deep within the earth below Alamut, which gives those who control it the ability to travel back in time. So right up to the last four words there, this is a pitch-perfect allegory for the Iraq war (or at least the liberal critique thereof). This in itself may not be interesting, but it is interesting that in the past three years we have had two mega-budgeted sword & sandals action spectaculars that serve as obvious allegories for the Iraq war – the other of course being 300 – and both of these place people from the Middle East in the conquering army role. And do note that the evilest of the evil in this film are the non-union equivalent of the Hashashin, who were of course a Muslim group, while the Persians themselves are ambiguously Zoroastrian. (I am not blind to the paratextual irony of having the Prince of Persia square off against the Assassins, but the religious subtext is also present, I think.)

But in Overthinking It terms, the thing to pay attention to is the heavy handed political subtext. As the film opens, the Persian army is debating whether to invade the holy city Alamut. Intelligence indicates that Alamut has the ability to produce powerful, high-tech weapons (i.e. really nice swords), and plans to sell them to rogue states and terrorist groups. One quick and brutal conquest later, the victorious Persian army marches through the streets of Alamut. Unfortunately, no cache of weapons is found. The Persian King is appalled. We need to find those weapons! Without them, our invasion becomes a war of aggression! We’ll never conquer the people’s hearts and minds! Indeed, later, we learn that the war wasn’t about weapons at all. Rather, it’s about a natural resource, buried deep within the earth below Alamut, which gives those who control it the ability to travel back in time. So right up to the last four words there, this is a pitch-perfect allegory for the Iraq war (or at least the liberal critique thereof). This in itself may not be interesting, but it is interesting that in the past three years we have had two mega-budgeted sword & sandals action spectaculars that serve as obvious allegories for the Iraq war – the other of course being 300 – and both of these place people from the Middle East in the conquering army role. And do note that the evilest of the evil in this film are the non-union equivalent of the Hashashin, who were of course a Muslim group, while the Persians themselves are ambiguously Zoroastrian. (I am not blind to the paratextual irony of having the Prince of Persia square off against the Assassins, but the religious subtext is also present, I think.)

Reimagining the invadees as invaders is not so strange, in and of itself. We’ve done it before with other wars, after all: witness Red Dawn. Or take this interesting tidbit, from the preface to Vladimir Lenin’s Imperialism: “In order to show the reader, in a guise acceptable to the censors, how shamelessly untruthful the capitalists… are on the question of annexations, in order to show how shamelessly they screen the annexations of their capitalists, I was forced to quote as an example — Japan! The careful reader will easily substitute Russia for Japan, and Finland, Poland, Courland, the Ukraine, Khiva, Bokhara, Estonia or other regions peopled by non-Great Russians, for Korea.” Lenin was dealing with actual legal censors, the writers of Prince of Persia and 300 were dealing with subtler censors of market pressure and the mind, but it’s still basically the same dodge.

Interpreted in this light, the film’s ending is creepy, if oddly poignant. Gyllenhaal manages to turn back the clock to the point where he first touches the dagger – the point, that is, immediately after his Persian army overruns the Alamutian defenses. Armed with the knowledge that the intelligence used to justify the war was flawed, he rushes to put things right by restoring the Alamutian princess to power, stopping briefly along the way to defeat the Dick Cheney analogue in a scimitar fight. The interesting thing about this is that he doesn’t go back to before the start of the war. Rather, he goes back to try to fix its aftermath. This is probably mostly for the sake of plot mechanics, but lets ride this puppy out: Gyllenhaal’s fix for the mess created by the invasion is to put the deposed head of state right back in charge. That is, to put Saddam Hussein right back in charge. That is, essentially to end Gulf War II the same way we ended Gulf War I.

The film is not meant to have a political point of view in this sense, of course: it’s not advocating anything outside of its own narrative. Restoring Gemma Arterton to the throne is a good thing because she’s meant to be a wonderful ruler, and this is not intended as an endorsement of Saddam’s leadership skills. The allegory simply isn’t that robust. Still, like I said: there’s something poignant about the film’s belief – or perhaps better, its desire to believe – that the people’s hearts and minds could be won simply by restoring the status quo, and that the bad intelligence about weapons was the ONLY reason for starting that war, rather than the straw that broke the camel’s back. And again, like I said: there’s something deeply creepy about this abdication of responsibility. Most people I’ve talked to about the current state of affairs in Iraq take on a mournful “you break it, you bought it,” kind of attitude. The end of the Sands of Time lets us live out the fantasy (however remotely, however transformed) of unbreaking it: of simply waving a magic wand and making the war go away, not by ending it and dealing with the consequences, but by preventing it from ever having happened, and then washing our hands of the whole mess. A nice thought, certainly, but not the way the world works. There are no do-overs in geopolitics. At best, we can make like one of Alfred Molina’s ostriches: bury our heads in the sand, and scream “La la la I can’t hear you!” (or make quacking sounds – whatever it is that ostriches do) until it blows over or everyone involved is dead, whichever comes first.

Painted on and overly-schematic as its political subtext is, Prince of Persia reminds us that there is a very real war going on. And in this, it provides a valuable service. But it may not be doing itself any favors. The head-in-the-sand approach can be awfully attractive at times. And Prince of Persia is currently getting clobbered at the box office by Shrek Forever After.

Oh, and of course no discussion of Jake Gyllenhaal playing a Persian political leader would be complete without linking to this.

I too picked up on the subtle political message in the movie and agree with nearly almost everything in the article.

Another thing that I picked up on was that every character in the movie had a British accent. At first I thought that this was simply an homage to the old movies when everyone in the Middle East had a British accent but then after wondered if wasn’t simply a way of showing how the English might have done it had they gone in instead of the Americans; trying to set everything right instead of acting like a bull in a china shop.

And you’re not the only one to show the comparison between Gyllenhaal and Ahmadinejad; Colbert featured that in his ‘Movies that are destroying America’ segment.

Good to see another Coupling alumni on the big screen!

I’ve yet to see this, but if the implication that Britain could have done it better, have a look at how we handled some of the Mandates (original Iraq, Israel/Palestine). I’m still pretty annoyed that we don’t have Persians to play Persians – I very much believe that there should at least be an attempt for ethnicity to play type (I don’t know if this is a position anyone from a particular descript ethnicity holds).

And finally, there are other uses for the Sands of Time: http://www.penny-arcade.com/comic/2003/11/14/

Awesome piece, Stokes. Nothing much else to say about the article itself, since I haven’t seen the movie yet.

But about British accents (and keep in mind this is from an American perspective): While it has, indeed, been done before, a bunch of British accents- whether natural or not, portraying people of non-British origins- it isn’t “old” in the sense that if done now it’s a throw-back or homage. It has been going on since film first started and has never *stopped*- that’s just how it is. I’d imagine it began that way because the first makers of film were rich white guys and the first actors were thus white; and for whatever reason, sounding European in America automatically denotes intelligence, superiority, etc. I’m inclined to call it a sub-consciously executed symptom of imperialism- white= better, and European is PURE white (or at least purer than American). In part, it may have also been (and still is) to form unity while still getting something foreign, yet all the while keeping it intelligible- Americans understand British accents better than Asian or Middle-Eastern (and I’m not judging whether this is right or wrong, btw). You never see movies rapt with French accents, even if set in France (“Chocolat”) or German ones when all the characters are German (“Conspiracy”)- they may have one or two people with the more “native” accent, but most of the people with accents, if they have them at all, have British ones (in “Chocolat,” set in France, only the main character sounds French, while everybody else sounds British or American; and “Conspiracy” is set in France, but the characters are all Nazis and their servants, and they ALL sound British and many are A- and B-list actors from Britain). And I think it still goes on today because it has been going on that way for so long. It’s the modus operandi, and there are not enough actors and actresses of other ethnicities famous outside the countries they’re ethnicities come from to fill in the void. (And in the case of Native American actors, since they are, well, natively American, there are few enough Native Americans as it is, let alone working actors.)

This is cyclical, of course. Minorities don’t get the chance, so there are fewer minority actors and actresses, but there are fewer of them because they don’t get the chance.

And this lack of actors and actresses, I think, is the main problem and reason NOW. And I’m not saying it’s intentional- it’s how film developed because of who was originally in charge and who was originally cast. It’s easiest to work off the old model. Still, this is why _The Last Airbender_ is being played by a mostly white cast (no matter what Shymalan wants to say) (oh, but of course the bad guy in this one is Middle Eastern, ahem). AND, this is why if you’re of Asian descent and lucky enough to make a casting call, you get cast as Korean one month and Japanese the next; this is why Graham Greene plays Mexicans, Lakotas, AND Navajos- they look the same, right?! Hogwash. I don’t know how heavily US film influences film from elsewhere, but it certainly doesn’t go the other way around very much, so if American cinema is going to change the accent problem, it needs to fix the problems with casting minorities in films; and they need to be cast not just as sidekicks and minor roles, but as major players and leads, and it needs to be done more often. Not only that, but they need to be in roles that are written universally- if there is no need for the character to be white, why should they be? It comes down to a fundamentally imperialistic lack of understanding or respect for different cultures, and casting ethnically “appropriate” actors and actresses is probably the easiest step in fixing that. Then you can tackle related problems where it isn’t just actors being shuffled from culture-to-culture, but cultures themselves (ahem, “The Karate Kid”).

So, in conclusion: Donald Glover SO should play Peter Parker!!!