[Note: Spoilers Abound. —Ed.]

Iron Man 2 came out this weekend and the critical reaction has been mixed. While most agree that the film is fun to watch, few seem to think that it was a good film. One of their key questions, posed also by Matt Wrather on the latest Overthinking It Podcast, is “What is this movie about?”

Numerous plotlines about a Russian scientist’s revenge, a rival’s attempt to take control of the Iron Man suit, Tony’s failing health and his relationship with his father were a little convoluted. Layered on top of that, Samuel Jackson, Scarlett Johansson and the setup for future Marvel Comics movies Captain America, Thor and the Avengers seemed weird and extraneous (though I really like the idea of building a cinematic continuity across a number of different properties and defended it on the podcast).

But beneath all of those plots, the Iron Man movies are ultimately about technological transition and the Ages of Man.

The ancient Greeks believed that history could be divided into five ages: Gold, Silver, Bronze, Heroic and Iron. Ovid and the Romans had a similar demarcation, omitting the Heroic Age of the Illiad and Odyssey. Both cultures believed that they lived in the Iron Age, an age of warfare, strife, suffering and greed.

Modern archaeologists, always living in the past, borrowed the idea of Ages when discussing prehistoric civilizations. The earliest tool users, as much as 100,000 years ago, started making weapons out of stone, hence, the Stone Age

Then, 5,000 ago, some genius discovered that if you melted copper and added arsenic or tin, you got a strong, durable weapon that would last longer and hold an edge better than the stone weapons he was used to. Tin and copper were hard to come by and involved massive trading networks from Britain to Babylon, but at that point, nothing beat a sharp bronze sword and suddenly you had the Bronze Age. Early smiths in the Caucasus Mountains in southern Russia were probably the first to forge bronze using the locally available copper and arsenic and it’s likely that many of them went to a painful and early death from contact with that arsenic. Progress is not without a price.

3,000 years ago, another genius figured out a way to generate enough heat to melt the much more prevalent iron ore that was sitting around all over the place. Iron wasn’t as strong as bronze, but at 5% of the Earth’s crust it was and is the cheapest metal around. Suddenly, everyone could afford a really shiny, sharp metal sword. It was the Iron Age and its technologies led directly into the Historical Age (when they started writing stuff down and we don’t have to rely solely on archaeology to know what went on) and world we live in today.

Early iron armor from the Middle East. Or, what happens to Iron Man if he stays out in the rain too long.

From out of a dark, cave-like building of mud bricks belching smoke and fire came these huge, magical, Age changing feats of ingenuity that shaped the world for the next millennium. The early smiths were the first scientists, the first engineers, the people who brought humanity out of the cave of the past and into the modern age of technology. For some perspective, the Stone Age lasted 100,000 years and has only been over for about 5,000. Some historians believe that its early monopoly on iron forging helped the Hittite Empire, based in modern-day Turkey, destroy Babylon and maintain a massive empire.

The men and, potentially, women who made this magic were seen as something above the rest of humanity, holding a secretive, mysterious power that was passed from father to son. In some cases, they even served as priests. In Jenne-jano, an Iron Age city in what is now Sudan, archeological evidence suggests that blacksmiths also served as diviners, rainmakers, healers and (gulp) performed rituals like circumcision. Their powers were so respected that even after the region converted to Islam, the blacksmiths held on to the respect of their communities.

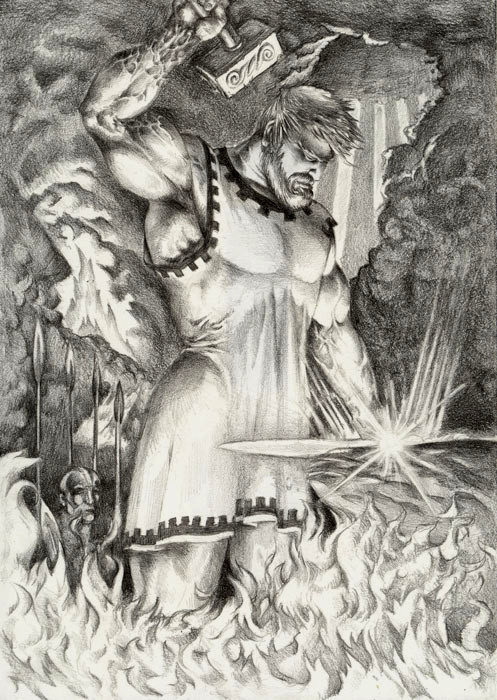

Smiths not only served as priests and seers, they were the only profession that actually had their own god. The only Greek or Roman god with a real job was Hephaestus (Rome’s Vulcan), the God of Fire and of Smiths. Other professions may have had patron gods, but even the Greek musicians would have admitted that Apollo’s lute playing was only a side gig to the whole driving-the-sun-chariot-across-the-sky thing. Hephaestus was the blacksmith of the gods, creating theirs weapons and armor, even building Apollo’s solar chariot.

He even married the Goddess of Love. Sure, Aphrodite cheated on him with Ares, but still, you’ve got to be pretty important to merit the actual Love Goddess. In addition, Hephaestus builds a number of automata, metal beings with personality and agency that help him in his work, arguably the world’s first fictional robots. Hephaestus had some serious parental issues, with his mother Hera tossing him off Olympus for being so ugly, crippling him. He only comes back to Olympus when they realize that they like his creations and send Dionysus to get him drunk.

Since then, iron and the people who deal in it have had a special place. In the stories of fairies and supernatural beings that were told throughout Medieval Europe, only the touch of cold iron can defeat the villainous beasties. That tradition survived into the last century, with iron horseshoes nailed above our doors for good luck.

Which brings us back to Iron Man.

The Iron Man films follow the transitions from one of these ages to another, with Tony Stark standing in for the smiths who perfected bronze and iron. The crucial scene in the first Iron Man movie has Tony Stark, wounded and imprisoned by an Afghani warlord, in the darkness of a cave. His only chance of escape and survival: using his superior technology. There’s a whole montage of building the suit of armor that he’ll use to escape, but the seminal image is of a man hammering out iron in cave lit by fire.

He succeeds, fighting his way from the darkness of the cave back to the light of civilization, not through his skill as a warrior but through his skill at the forge. His first weapon? His hands, the most important tool in any smithy. His second? Fire, which gives the smith the ability to turn ore into power.

Tony Stark has discovered a new kind of weapon that gives him an advantage over everyone else, and like those first iron swords of the Hittites, it’s a weapon that’s too expensive to go around. While the American fighter jets he inadvertently takes on may pose some threat to him, Iron Man can take one of the world’s most advanced weapons systems out just by flying through its wing. Like the first humans to move from rock to bronze, he has an advantage over his contemporaries that sets him apart, gives him power and allows him to, as we learn in the beginning of the second film, “privatize world peace.” Like those early bronzesmiths, Tony Stark comes across as a sort of god, wielding mysterious powers that others can’t really comprehend.

The second film takes us into the second phase of any age, the period of proliferation. As the recording industry continues to misunderstand, once a good idea has been made public, people are going to copy it. The first American nuke went off in 1945. By 1949, the Russians had one too. Similarly, the Hittites couldn’t hold on to iron forever and within 200-300 years, most of the Mediterranean world and the Middle East had entered the Iron Age.

Congress is worried that soon, the Iron Man technology will spread, giving the whole world access to this powerful destructive force. And so it happens. Within months, a unusually badass scientist, Ivan Vanko, has perfected his own Arc reactor, weaponized it (in a potentially very self-destructive way – whips? really? Don’t you remember how Indiana Jones got that scar?) and gone up against Iron Man. With the help of a Rolls Royce and an aggressive chauffeur, Iron Man beats Vanko’s ass down.

But by the end of the film, Vanko has teamed up with a rival military contractor (the modern equivalent of a rival empire?) to create a whole army of iron men, ready to take over the world. He and Don Cheadle manage to take them down, but though the movie doesn’t discuss it, the plans are out there, the government wants them and there’s nothing that can be done to put the genii back in the bottle. Sam Rockwell’s parting threats to Pepper Pots suggest that he and his technology will be back.

Inside sources say that Robert Downey Jr. turned down an offer to play the Son of Vulcan, another smith god based character.

In Iron Man 2, Tony echoes the plight of those first arsenic-riddled bronzesmiths, poisoned by the same element that gives him his power. Like those ancients, his only solution is to find a new element – tin in their case, mcguffinium in his. Power comes with a price, but it’s a price that can be paid with hard work and ingenuity.

Like the ancient smiths, he is a conduit to the primal powers of earth and fire from which the modern age is born. And like the smith god Hephaestus, Stark lives on a mountaintop looking down on the world, surrounded by beautiful women and automatons that help him shape the technologies of the future. Like Hephaestus, he has deep parental issues that he can only solve through the act of creation and the generous application of booze. If you waited until after the credits, you know that pretty soon, he’ll be hanging out with an actual god who also likes big hammers.

Ultimately, there’s not a single answer to “What is Iron Man 2 about?” because Iron Man 2 can’t be taken on its own. When put in the context of Iron Man and the future Avengers films, it’s a second act in a story that’s an allegory of how we got out the cave and into the movie theater in the first place.

I like the joke, but just to clarify: Stark invents/discovers/creates/whatever Vibranium in the film.

Really? Vibranium? He’s a dirty, dirty man.

One thing that I forgot to work into this piece is the concept of a singularity, a moment when culture has changed so much that the world and its technology become incomprehensible to people who came before. It seems that in Iron Man 2, Tony Stark is that singularity. Both in terms of the technology and the fact that he’s the first public superhero, he seems to have completely changed the game.

The example at http://io9.com/5534848/what-is-the-singularity-and-will-you-live-to-see-it is “imagine explaining the internet to somebody living in the year 1200. Your frames of reference would be so different that it would be almost impossible to convey how the internet works, let alone what it means to our society.”

Frankly, I don’t believe that a singularity can exist. The men who smelted bronze would have understood iron. My grandfather grew up in a town without electricity, but understood the internet before he passed. His frame of reference wouldn’t have been too different than that of his mother, which wasn’t that different from that of her mother, etc…

The technology may change quickly, but human evolution is a slow process. We interact with the internet through sight, sound, touch, and, soon god willing, smell and taste. We created language to be able to convey and transmit the things we see, hear, feel and smell. We did a good job of it, and there’s nothing that does or can appeal to one of those senses that can’t be conveyed in speech.

Still, an interesting concept. Thoughts?

It was good to see the proliferation of technology at the fore of the movie. Too often, movies work from the Great Man philosophy of science, where if you take out an important inventor, or change his mind, some critical piece of technology is just gone, a la Terminator 2, where getting rid of Dyson and The Chip theoretically eliminates Skynet. Of course, that seems to derive from looking at the history of 18th and 19th century science. The big names dominate there, like Newton, Einstein, Darwin, Pasteur. You still see that reflected today… usually only one scientist predicts the event, only one maverick knows whats really out there. But thats not the way modern science works… everyone builds off of existing science, and almost no one does it in a vacuum. When Pasteur developed Germ Theory, he must have been one of a few dozen scientists. Now he’d be one of tens of thousands. Even knowing Tony Stark had a portable energy plant, laser hands, and armor that could shrug off a missile tells us a lot about what is possible that we don’t know. I think that was my biggest problem with Tony, it wasn’t that he wasn’t awesome, it was just that he was naive about his own advanced ability. But I suppose if you spend all your time with bimbos, you forget that their are other scientists out their with their own boxes of scraps.

Thank you for a great article. This reminds me of how I watched How To Train Your Dragon only recently and kinda saw it as a parable about the transition from a passive submission to nature towards a modern scientific approach. If I was able to write an interesting article about it, I think it would feel similar to this one right here. If you’ve seen HTTYD and you’d like to discuss it, I’m right here for ya.

Yenzo: We encourage you to try anyway! Check out our submission guidelines, then hit us up at [email protected]. We love guest writers.

Something that bothered me in the movie is when someone (I can’t remember who) says that Iron Man is our new “nuclear deterrent”. If you continue the “ages” construct, we’re still firmly in the nuclear age (unless you want to look more broadly and say we’ve passed into the “information age” or the “cyber age” or whatever). Nuclear weapons pose a strategic threat to entire nations and an existential threat to the whole world, while Iron Man is a tactical weapon; they never even try to explain how he is enforcing his privatized world peace, and his contribution would be inconsequential in a full-blown nuclear exchange. Even in a large conventional conflict he would probably serve best as a fancy sniper, going after high-value, well-protected targets instead of trying to engage large military formations in the field.

To make the argument that Iron Man represents a transition to a new age, you’d probably need to focus on the arc reactor technology and it’s strategic use, instead of powered battle suits.

A more-compelling stinger along these lines may have been to show packages from Vanko containing small arc reactors and detailed plans being posthumously delivered to all the “bad guys” (Iran, North Korea, etc.) referenced at the beginning.

@Mark: Yeah, that was a problem with the film that really mired it in the past. The whole thing seemed like a movie my Dad might make. Up to and including the AC/DC soundtrack. (Don’t get me wrong, I heart my AC/DC, but can you really unselfconsciously feel that something badass is going on listening to that? I mean…my Dad could…)

But yeah, strategic wonkers noticed pretty quickly after the dawn of the nuclear age that nukes wouldn’t make conflict impossible as Nobel had hoped, but would just make unconventional warfare proliferate. This is exactly what has since happened and we can be said to be well into the post-nuclear age.

The whole US v. Russia/nuclear thing is so 20th century. Add to that the absurd cliches of Russian life depicted in the 1st act and the whole show seemed dated and irrelevant. The Gates/Jobs/Hammer/Stark thing just seemed like a pathetic attempt to be current.

For some real juicy updating of Iron Man check out Matt Fraction’s work on the comic series. Stane’s son builds an open-source repulsor suit out of Stark tech scavenged on the black market. Corporate dinosaur Stark has to take on lithe nimble startup Stane Jr. Good stuff.

@bregman

Having some personal experience working with a lot of Russian scientists who emigrated in the mid 90s, I actually think the movie’s depiction of Russia isn’t as silly as you might think. Moscow and St Petersburg are both very nice places now, being the center of most of Russian life currently, but the rest of the country suffers from a lot of Post Communism Syndrome… most towns are built around a single bloated, inefficient industry, and the economy is held up by oil/metal exports. Russian science is in poor straights too, since all the professional people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s left for the West as soon as they could. So all thats left are students and very old scientists in their 70s. This is just the sort of environment, with lots of loose high tech equipment from failed businesses, an aging scientific establishment that would not grasp or fund ideas, and a fairly corrupt political culture, that could lead to someone like Vanko.

Remember when Stark and Stane are fighting and Stane starts talking about the Manhattan Project? Something like “What would the world have been like if the scientists thought it was too dangerous?”

My first thought was of the Szilard Petition, the attempt by some of the Manhattan Project scientists to first demonstrate the bomb to the Japanese high command and scare them into surrender before using the bomb against a civilian population. It was headed by Leo Szilard, the first person to come up with the idea of the nuclear chain reaction, and incidentally the man who drove Einstein to his meeting with Roosevelt which eventually lead to the Manhattan Project. After the Nazis were defeated, there was no longer the fear that the Germans would have the weapon first – instead, General Groves just wanted an excuse to whip out the weapon.

My second thought was, “Hey, maybe scientists should have taken control over the nuclear arsenal” – most of the top dogs on the Manhattan Project declined to take part in developing hydrogen weapons.

So Stark’s refusal to hand over the Iron Man at the beginning of the movie makes sense as his own version of Szilard’s Petition – he’s seen what the military’s done with his weapons, and he doesn’t want to be part of that. But the events of the movie prove to him – and to us – that he can’t handle this entire burden of responsibility that he’s assumed. So he lets Rhodey take a suit. Which means that the military has the suit after all. But at least it’s being held by General Eisenhower instead of General Groves.