(Continued from the previous post.)

16) Black Dog Serenade

“My Funny Valentine” was in many ways emblematic of the new direction that Cowboy Bebop seems to be taking: a story that’s basically about character, with strange, kicky dramatic beats, and a pervading sense of quiet surrealism. (The same could be said of #14, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” for that matter, which is why I say that it’s a new direction rather than one atypical episode). By that standard, “Black Dog Serenade” is kind of a throwback, because it is BAD-ASS.

Bad ass.

And it is an awful lot of fun, I’ve got to say. Fad, Jet’s old partner from his police days, pulls him back in for one last score (more of a drug dealer trope than a cop trope, but whatever), in order to track down an escaped convict who just happens to be the guy that shot off Jet’s arm. It is noir as all get out – in the visuals,

I like that the difference between "Cop Jet" and "Classic Jet" is that Cop Jet keeps his beard trimmed.

in the score, which is mostly a muted trumpet version of Jet’s signature tune, “The Singing Sea,” and in the narrative, which muddles betrayal, and fate, and revenge, and professionalism, and machismo, and honor, and cigarette smoke into that rich, black, frothy cocktail which is the stuff that dreams are made of. Like, there’s a point where the assassin gets the drop on Jet and almost shoots him in the head, but Jet is able to block the bullet with the robotic arm that the assassin saddled him with. It doesn’t come much more noir than that.

Oh, and of COURSE it turns out that Jet’s old partner is corrupt, and was the one who shot his arm off in the first place. I mean, that’s almost obligatory, right?

But fun as this episode is, there isn’t that much to say about it. So although “My Funny Valentine” seems like a smaller episode in a lot of ways, it’s actually a lot more robust. There is one interesting character moment here, though. If we look at the Bebop’s crew as some kind of messed up family unit, it’s pretty clear that Jet is the father. He’s always the one who tries to be responsible, he’s always the one who scolds the other crew members and holds their feet to the fire, he’s always the one who tries to make sure that the kid and the dog get fed on time. (Also, he has some seriously stone-age sexist attitudes that he brings up in public every now and then, which the people who care about him seem to do their best to ignore. He’s not just the father-figure: he’s the patriarchy!) What’s interesting is that when he’s part of the Jet+Fad team, he plays the same role that Spike plays in the Jet+Spike+Faye team: running off half-cocked, pointlessly risking his life, taking on an unspeakable badass in a close-quarters knife fight more or less just for the hell of it. The way that Fad dies in his arms at the end of the episode even has some resonance with the way that Rocco and Gren each died in Spike’s arms in their respective episodes. So if “Black Dog Serenade” explains anything about Jet’s character, it’s his weird co-dependent relationship with Spike. He never actually comes out and says “You remind me of myself, when I was your age,” but after watching this I’m not sure he even needs to.

17) Mushroom Samba

And now, the Radical Edward episode. Back when Mlawski was trying to sell me on the idea of Cowboy Bebop, she mentioned the “crazy blaxploitation episode,” and as a result I was not caught completely flatfooted by this one. Still, I was not entirely prepared for just HOW crazy it would turn out to be.

This is another one of those Cowboy Bebop episodes that turns on the fact that the crew never has enough to eat. (Other episodes which hit this note include #1, #4, #6 and #11, although none of the others hit it quite this hard.) After establishing that the crew is hungry enough that they seem to be considering eating Edward,

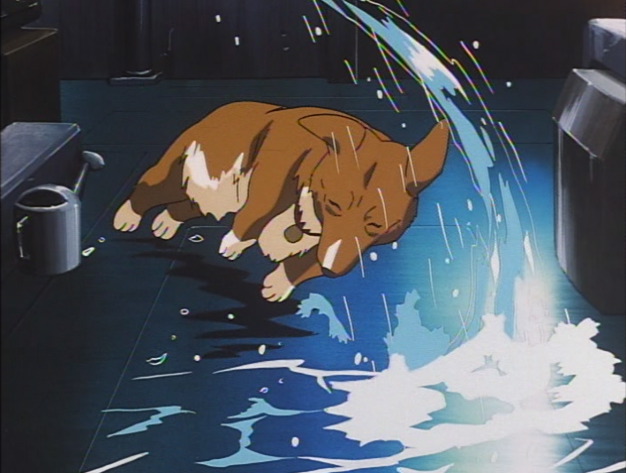

the writers arrange for the BeBop to be sideswiped by a hit and run driver, resulting in a crash landing on a desert planet. While Spike and Jet try to fix the ship, and Faye battles a case of explosive diarrhea (seriously, that’s what happens), Edward is sent out to find some food. As you might imagine, this is not a great idea. The crew seems to be in danger of literally starving to death – you’d think that food would be enough of a priority that they would assign the task to someone who is mentally competent.

Domino

Anyway, Ed pulls an electric scooter out of the hold (which is to say: out of the writers’ collective ass), and peels off into the desert in search of sustenance. Through a wacky set of coincidences, she ends up first dosing the rest of the crew with magic mushrooms, and then deciding to play bounty hunter by chasing down Domino, the psychedelic mushroom smuggler. Domino is being chased by two other people as well. One is a bounty hunter named — you know, I’m not sure if we even ever hear her name, but let’s call her Pam Grier, because I mean, well, obviously, right?

Shaft.

The other – not a bounty hunter, but a man pursuing personal vengeance – is named Shaft. And I don’t mean that’s what we’re going to call him: I mean that’s actually the character’s name. Eventually they all end up in a massive, convoluted action/chase set-piece (set over a literal samba tune about mushrooms, making this the most literal episode title yet), on and around a speeding train. There’s no way to do this awesome sequence justice in words, so I’ll just give you a big string of pretty pictures to look at – these pretty much convey the sense of it, although it’s well worth watching for yourself so that you can savor the comic timing and that wonderful music.

Now, what’s interesting is that once Ed catches the guy, he offers her his stockpile of magic mushrooms in exchange for his freedom, claiming that they’re much more valuable. She accepts without even pausing: bringing in the criminal is not something that she cares about even a little. So that’s shoe-drop number one. Shoe-drop number two comes when the police raid the BeBop crew’s camp and test the mushrooms… only to find that they are ordinary, and relatively valueless, Shitakes. And the episode ends with the crew eating a massive mushroom banquet.

Ed is overjoyed: they have food! Delicious food! And Ein, who also gets mushrooms, is pretty much fine with it. Everyone else goes right back to moaning and groaning about the lack of variety in their diet, and never mind the fact that Edward’s fungal bounty has literally saved them all from starving to death. In the English dub, Jet has a great line – it’s hard to capture the delivery on the printed page, but let me see if I can give you the gist:

Jet (defeated): “Shitake stir-fry, shitake stew, shitake salad and SHIT –

“-ake on ice.” Where the censors were on that one, I don’t know.

This episode is fascinating, fascinating to me, and here’s why: Ed is clearly better at bounty hunting than anyone else on the BeBop’s crew. Oh, we have seen them capture people before. And technically, she didn’t get the bounty on Domino. But she does bring home the mushrooms. The idea of having enough food has been a constant leitmotif in Cowboy Bebop: Character after character complains about not having food, or fantasizes about the food they’re going to buy once they finally do have money. The whole point of bounty hunting is that if you do it enough, you get to have a banquet. Ed brought home the mushrooms! This is the only episode so far where they do get to have a banquet. Even in the episodes where the crew successfully captures someone, you never, EVER get to see them enjoying the reward. (Faye’s banquet in “My Funny Valentine” took place in flashback, and was unrelated to bounty hunting anyway.) So when I say that Ed is better at bounty hunting, I don’t mean that she’s better at getting the job done: I mean that she’s better at getting the end-benefit which is the ostensible purpose of doing the job to begin with.

Now this could just be a cute little gimmick. It’s not unusual, in shows with a mooncalf character, for said mooncalf to be preternaturally gifted or lucky at everything that he/she does. But I think that it’s actually part of a broader pattern that this silly episode uses to drive home a very serious message. To wit, “You’ve got to quit all that ‘giving a damn’ nonsense, because it’s just going to get you killed.” Ed’s success doesn’t really come from luck. It comes from her ability to live in and for the now, rather than getting hung up on some idyllic and fully consummated future state.

Two examples from the episode itself make this point clear. When Ed ambushes Domino in his hideout, she pulls out a gas gun and shouts “Stink Bomb Attack!” From the picture, you can see that she hasn’t quite thought this through. You could say that this shows an absence of planning. I say it shows a difference in priorities. Yes, tossing a stink bomb at Domino is not going to be as effective as, say, tasing him, if your goal is to capture him. But Ed’s goal is simply “stink bombs are hilarious!” And in that case tasing him is going to be decidedly suboptimal.

Contrast this with Shaft’s motivation. Shaft’s brother died from eating a tainted mushroom that Domino sold him. Since that day, Shaft has been walking the earth dragging a coffin behind him, waiting for the day that he could track Domino down, kill him, and stuff his body in the coffin. That’s a pretty epic plan, in its grim and terrible way. But here’s the thing about those epic plans: the universe doesn’t care about your dead brother. Or your plan. Or your fancy coffin.

"And I'm going to put your body in -"

CRASH!

"D'oh!"

Now, the image of someone dragging a coffin around with them is pretty obviously drawn from Moby-Dick (which is also the name of the cafe where Shaft goes to drown his sorrows in ice cream after his coffin gets smashed), and this makes a lot of sense too. Because the message of Moby-Dick is basically the same as the message of Mushroom Samba: all that “giving a damn” nonsense is only going to get you killed. What, after all, is Captain Ahab, but the giver of the greatest possible damn? What is Radical Edward, but a jovial Stubb trapped in a world full of madly tilting Ahabs? And this is also the message (or one possible reading of the message) of all those earlier episodes where people have to dig up and relive the traumatic events of their pasts. There’s a line near the end of “Black Dog Serenade” where Fad complains that Jet couldn’t let go, couldn’t just leave well enough alone. Jet’s response – the whole episode’s response, really – is that of course he couldn’t, because that’s not what a Man does. He keeps digging until he finds the truth, even if it kills him. This is a very standard noir trope, maybe the noirest trope there is. But although the noir hero’s behavior is generally held up as brave, it’s actually thoroughly conventional. Mushroom Samba, on the other hand, dares to suggest that one might want to think about actually… letting… go!

(Incidentally, this is not unheard of within noir itself. The book version [spoilers ahead] of The Maltese Falcon pretty much comes to the decision that taking the noir hero route makes Sam Spade a giant asshole, and the hero of The Glass Key (also by Dashiell Hammett), gets to live happily ever after because he’s willing to walk away from a fight. But it’s not very common. When the Coen brothers remade The Glass Key as Miller’s Crossing, they decided to change the ending to a typical noirish downer.)

So, what else. That’s pretty much it as far as the main plot goes. But isn’t it interesting that this episode, where there is literally nothing at stake at all, is so much richer for analysis than the “weighty” Black Dog Serenade?

We should also take a minute to analyze the three main characters’ acid freakouts.

Spike finds himself climbing an infinite staircase, which we’re told is “The Staircase to Heaven.” I take this to mean that he has a death wish. Pretty obvious, really. Although it is funny that he wakes up in the morning on top of the BeBop, looking around like “How did I get up here?!”

Faye goes into the bathroom and imagines herself in the kingdom of the fishes. This isn’t meaningful as such — but there’s a pattern of images at work here, where Faye and things from Faye’s life are shown to travel into and out of some kind of watery abyss. In “My Funny Valentine” we had an editing juxtaposition of Faye being pulled from cryo storage and Jet pulling a package of frozen fish out of the BeBop’s freezer. The insurance company that froze her in the first place is called “Tortus,” i.e. turtle. We’ll get into this more in the discussion of the next episode, which is all about Faye. Her morning after shot is also kind of funny, although for some people the idea of putting toilet paper in your mouth is too gross to even laugh at.

As for Jet… Jet is an interesting case, because we never get to see what he sees. He seems to have a really good time, yukking it up with his pet bonsai trees, but we only see his delusion from the outside. I think this might mean that the writers are pretty much done giving him any character development. He’s made his peace with the woman what done him wrong, he’s gotten revenge for his busted arm, he’s beginning to establish emotional ties with the people around him… maybe there’s nowhere else to take him. But as for his morning after shot…

Okay, yikes.

While it’s probably a given that any “crazy blaxploitation” episode is going to have its share of uncomfortable racial moments, this one stapled my eyebrows to my hairline, as did all the business with the watermelons. Granted, Jet wasn’t actually putting on blackface. Granted, the only character who really shows any interest in the watermelons is Edward. Still, it’s VERY uncomfortable, and needs a little explanation.

Cowboy Bebop tends to rework earlier pop culture in a way that is, for want of a better word, cubist. You see lots of individual facets — symbols, images, themes — of Kung Fu movies (in “Stray Dog Strut”), or the Alien franchise (in “Toys in the Attic”), or Film Noir (passim) or whatever it might be, but the individual facets aren’t connected to eachother in the way that you would normally expect. The other thing to note is that these exploded pop culture artifacts are never really the main point of the episode: they’re just a backdrop for some completely unrelated story. “Mushroom Samba” is no exception. The backdrop is a cubist reworking of “Hollywood’s depiction of African Americans, from the 1920s to the present.” The main point of the story, which I covered at length above, has nothing to do with this. And to an American audience, this is really hard to take, because to an American audience a lot of these individual symbols are straight-up Unclean Things that can only be handled while wearing the narrative equivalent of a hazmat suit. An episode of Cowboy Bebop that was about race relations would be one thing. An episode where Shaft, and watermelons, and giant painted-on lipstick grins are just sort of casually floating around the background for no good reason? Is quite another. Before we get too offended, we should remember that Cowboy Bebop was produced by and for Japanese culture. The racial traumas that shaped our society did not shape theirs, and this means that the standards for what constitutes “racism” in art have to be a little different. But if it’s a Japanese show, I’m still an American audience, and I don’t think it’s responsible (or really even possible) for me to slip on some special Japan-o-Specs and try to watch this episode from a place where these symbols are not disturbing. Like the gender/sexuality stuff in “Jupiter Jazz,” or the disability stuff in “Waltz for Venus,” or the little whiffs of misogyny that keep on popping up all over the place, it’s something that you have to confront and deal with if you’re planning to really enjoy the show.

Not part of a hallucination, believe it or not.

18) Speak Like a Child

This is the episode where the “Coming Next Week!” crawl ends with a sheepish admission that the story is kind of pointless. But if you’ve been watching the show along with me, you’ve probably gotten in the habit of never trusting a flippin’ THING that the writers tell you. So if they say that this one is not important, it must be super, super important, right? Right! Nothing much happens on the surface, true, but this episode has unplumbed depths. (HA!) Don’t get the joke? Well I’ll explain.

So, there’s a term that pops up in literary criticism, “mise-en-abyme,” that has a few interrelated meanings. It refers to placing something between two mirrors, so that it is reflected infinitely. From this (possibly), it also refers to images or stories that contain smaller copies of themselves (you know, like “It was a dark and stormy night. The Captain stood upon the deck and said, “Tell me a story, my son!” So I began: “It was a dark and stormy night. The Captain stood upon the deck and said, “Tell me a story, my son!” So I began: “It was a dark and stormy night… etc.” etc.” etc.” etc.”). And from this (again, possibly), it also takes on the more general sense of any story-within-a-story construction, and any aspect of a fictional work which draws our attention to the fact that the work is fictional.

My read on “Speak Like a Child” is that the writing staff decided to make an episode which is mise-en-abymed out the freaking wazoo. By which I mean that this episode plays with mise-en-abyme the way that the last episode plays with Blaxploitation. Although in this case, the background texture and the episode’s real point are not completely unrelated… but maybe I’d better get around to explaining the plot.

The episode kicks off with Jet telling Ed the story of Urashima Taro, a Japanese Rip Van Winkle analogue who traveled to the Dragon King’s palace on the bottom of the ocean, spent one night, and returned to land only to find that 60 years had passed. So right off the bat, note the resemblance to Faye, who spent almost 60 years in cryogenic storage (mise-en-abyme count=1). This is interrupted by the delivery of a mysterious package addressed to Faye, which – we later learn – has been bouncing around the solar system since before she went into cold sleep. Note that it’s delivered by the Turtle shipping company – another connection of Faye’s past to a nautical symbol, and a direct connection to the Urashima Taro story, which features a turtle heavily. The connection of the (ostensibly real) main narrative to the (obviously fictional) fairy tale draws our attention to the fact that the main narrative is fictional. Mise-en-abyme count = 2.

Now, Faye doesn’t know what’s in the package, so she assumes that it’s from a collection agency, and runs off without opening it. Spike, being a curious sort (although… since when?) opens it anyway, revealing a videocassette, i.e. still the dominant TV recording medium at the time when Cowboy Bebop was being aired. (Mise-en-abyme count – henceforth MEAC, because boy howdy we are going to be see a lot of that phrase – equals 3). No wait! Urashima Taro famously came up out of the ocean with a magic box that he was told never to open, and when he did open it – they always do, in these stories – it turned out to contain all of his lost years. And here we’ve got this cassette, which is kind of box shaped, and they can’t get at the information inside it, and it contains the secret of Faye’s lost past. So the MEAC is at four already. At least.

(Incidentally, just to get this out of the way: Faye spends the rest of the episode gambling on horse and grayhound races, before finally deciding that she misses her friends, and coming back to the BeBop. The fact that she makes this decision is a crucial, crucial moment for her character arc, even if she doesn’t quite admit it to herself yet. And while we’re on the subject of character development, the fact that Jet is telling Ed a fairy tale is also kind of significant, because it marks his transition from someone who is serving in loco parentis by keeping Ed fed and clothed, to someone who is actually trying to be a father. But both of these important psychological developments are more or less glossed over in the show itself, so I’ll give them similarly short shrift here.)

Anyway, Jet and Spike decide that they want to know what’s on the tape, so they track down a vintage electronics collector. And yes, when they come into his shop, he’s watching an episode of Beverly Hills 90210. He helpfully informs them that what they’ve got there is a beta cassette, and launches into a rapturous description of the rise and fall of betamax. Now, this guy is pretty clearly supposed to represent the show’s own creative team. He fetishizes dead recording media the same way that Watanabe et al fetishize dead narrative genres. Remember that a betamax player, in 1998, was already basically junk. Beautiful junk, sure, but not a viable option. The same is true for the cultural detritus that makes up the basic fabric of the Cowboy Bebop universe. (I’ve gotta say, I find it interesting that the writer stand-in character is portrayed as such a giant flaming nerd. Oh, and MEAC=5).

They start playing the tape. Will all the mysteries be revealed? Answer: have you even been watching this show? We do get some tantalizing shots of a city (Singapore, according to the all-seeing Internet), and some schoolgirls – is that a young Faye Valentine? – before the tape jams, and Spike tries to fix the player the way he fixes any broken electronic device…

What. The. Hell.

Having successfully destroyed one of the two remaining betamax players in the world, Spike and Jet go after the other one, which lies buried in the ruins of Akihabara, Tokyo’s famous electronics/nerdly-goods district, which in the world of Cowboy Bebop has sunken into the sea.

• The BeBop travels to Japan for the first time? MEAC=6.

• The characters from Cowboy Bebop head out to the kind of place where fans of Cowboy Bebop might be expected to shop for Cowboy Bebop merchandise? MEAC=7.

• The narrative requires Spike and Jet to literally descend into an abyss?!?!

MEAC meter begins to spin wildly, and explodes in a shower of sparks. Which could itself be seen as a self-referential nod to the collector’s broken Beta deck, and… Oy. This is making my head hurt.

So yeah, it’s that literal trip to the bottom of the ocean that I was referencing in my “umplumbed depths” line. That and the fact that they do spend a bunch of time literally exploring plumbing.

But after a bunch of these “let’s go spelunking in an abandoned building” sequences (which accomplish precisely nothing, in narrative terms), Jet and Spike find what they were looking for.

Don’t ask me how they’re planning to get these back up that bannister slide from the top of the page. They manage it somehow, because in the next scene we see them returning victorious to the BeBop, where they find…

…that they accidentally picked up a VHS player instead. Bwaaaaa-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!

And do note that the “much labor for no reward” structure that informs most of the actual bounty hunting is preserved in this episode as well. The shattered MEAC meter vibrates weakly, making a dull clacking sound.

But then, just as they’re about to give up hope, another package arrives, again addressed to Faye, which contains a working Beta deck. (This one was delivered by the Rabbit shipping company, which for obvious reasons got there much later than the Tortoise shipping company.) And then the episode ends with everyone watching the movie, which turns out to be a video diary that young Faye made as a message to her future self.

Wow. WOW. If that meter wasn't already broken, this would have killed it for sure.

And then, finally, after all this signification, the thing itself. Smug little so 'n so, aint she?

Quite aside from the mise-en-abyme factor, there are a couple of important things to point out about that tape. One is that Faye’s handheld camera work continues the pattern of Faye-POV-shots that was established in “My Funny Valentine.” The second is that it’s SUCH a weird, spectral, uncanny moment. Faye has lost her memory, remember, and watching the tape doesn’t bring anything back (at least not yet, although there are a few episodes still to go). So she’s sitting there, watching the younger self she doesn’t remember. And at the same time, the young Faye is delivering this message to an older self that she can never possibly meet. (So again, it’s like facing mirrors – but like I said, let’s leave the mise-en-abyme out of it.) I think this speaks to something very true, and very human, about our experience of self and our experience of time.

Obviously some parts of Faye’s particular experience are contrived… Childhood memories are usually a little hazy, true, but perfect amnesiac breaks like the one that Faye has do not often occur outside of fiction. And some of the lines that young Faye delivers – things like “I’m not there anymore… but I’ll always be here, rooting for you, my only self!” – are really too perfect by half. But there’s still something recognizable about it. If I think back to myself at age 14… well, I’m not that guy anymore. He is gone. Dead and. (And note the thematic resonance with Chessmaster Hex from “Bohemian Rhapsody.”) Although we can try to trace our personal development from point A to point B, this being to an extent the basic goal of psychoanalysis, there’s always going to be a certain black-box aspect to it. The past, too, is a watery deep. It shapes us, in a sense it is with us always, but we can no more return to it than Urashima Taro can return to the Dragon King’s palace, or Faye Valentine to the Singapore that was.

I love, love, love the fact that this episode ends while they’re all still watching the video. The narrative is basically a series of internments and exhumations, right? Young Faye’s message is buried in the antique technology, then they pull it out with the right player. Faye goes away from the Bebop and buries herself in the anonymous atmosphere of the racetrack, but then she climbs back out and returns to the BeBop. Spike and Jet go down to Akihabara, and then come back up. But then at the end, everyone (the viewers, the characters, all of us) gets immersed in the show-within-the-show of Faye’s video… and the episode stops before we can come up for air. It’s a subtle effect, but a powerful one. More than any other episode so far, you walk away from this one in an altered psychological state.