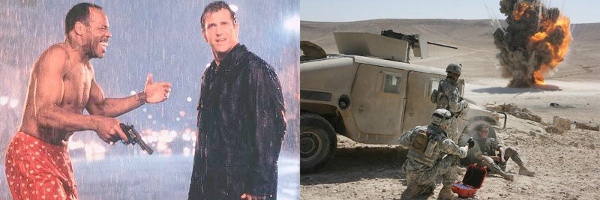

"Buddy cop blocking"

Mild spoilers for The Hurt Locker will follow. Although if you haven’t seen it and aren’t planning on seeing it tomorrow, I’m not going to give away anything that will ruin it, and I might help you understand what all the fuss is about.

Is this familiar to anybody?

Sergeant [JT Sanborn] is an [aspiring] family man and sensible veteran [soldier] just trying to make it through the day unscathed. [Staff] Sergeant [William James] is a suicidal loose cannon [bomb defusing specialist] who doesn’t care if he even lives to see the end of the day. Reluctantly thrown together to solve the mysterious [bombing of a street in Iraq], the unlikely duo [encounters] a dangerous ring of [Iraqi insurgents] employing ex-military mercenaries. After a tragic turn of events, the mission becomes personal and the mismatched investigators must learn to trust one another as they wage a two-man war against [ennui, meaningless death and the inhumanity of neocolonial geopolitics].

Oh, I know where I saw this! It was drawn from an IMDB Plot Summary:

Sergeant Roger Murtaugh is an aging family man and sensible veteran police officer just trying to make it through the day unscathed. Sergeant Martin Riggs is a suicidal loose cannon cop who doesn’t care if he even lives to see the end of the day. Reluctantly thrown together to solve the mysterious murder of a banker’s daughter, the unlikely duo uncovers a dangerous ring of drug smugglers employing ex-military mercenaries. After a tragic turn of events, the mission becomes personal and the mismatched investigators must learn to trust one another as they wage a two-man war against a deadly criminal organization.

Look familiar? Unless you’re one of OTI’s valued younger readership, it should. It’s from 1987’s Lethal Weapon, perhaps the definitive “buddy cop” movie of the last forty years, made back when Mel Gibson was the sexiest man alive.

Yeah, the world has turned upside down several times since then. I hear there’s an iPhone app that can measure the rotational velocity. But one thing has held constant – the buddy cop movie is still close to all our hearts. Oh, except now they give it Academy Awards (or maybe they will – check out the Oscars next weekend).

How far does the similarity between The Hurt Locker and Lethal Weapon go? (Farther than you think) What are the differences? And what does this say about how we’ve changed as people since the salad days of Riggs and Murtaugh? Read on…

Let’s start by watching the trailers – partly because they are awesome:

(In case you couldn’t figure it out or YouTube broke the links, the first one, the one with the awesome 80s special effects, isn’t the one up for an Academy Award next weekend.)

"If you weren't so good at your job, I wouldn't work with you, because you are crazy and dangerous and are going to get me killed."

But let’s run it down, shall we? White guy and black guy don’t get along. One is by the book, the other doesn’t follow any rules, but is just so … damn … good … that it doesn’t matter. The crazy guy kind of has a death wish and feels bad about his failure to take care of his family, while the by-the-book guy manages to more successfully compartmentalize his life, despite how disruptive the crazy guy is. Some kid or girl or something is threatened, which tests the buddy cops’ relationship and gives them something to agree on. There is a thoroughly implausible action sequence about once every ten pages.

Key lines to watch for:

- “Get out of my way and let me do my job.”

- “You’re going to get us all killed!”

- “You’re crazy; you know that?”

- “I’m too old for this shit.”

(To my knowledge, Jeremy Renner in The Hurt Locker is the only man every nominated for a Best Actor Oscar in a movie where he actually says “I’m too old for this shit.” It’s in the scene where he’s sitting on the bed smoking. I didn’t believe it either.)

Other key tropes to watch for:

- Ineffective superior officers who are kind of jerks

- Crazy guy smokes to signify to the audience that he doesn’t care about his safety

- Friendships with men taking the place of loose relationships with women and children you rarely see

- Going off-mission in ridiculous, self-destructive ways that no professional department of this sort would ever allow

- Third wheel guy who is little, incompetent and angry but who comes up big at a key moment (This is one of two main points where The Hurt Locker resembles Lethal Weapon 2 more than Lethal Weapon 1, the other of which I’ll get to later)

- “How long does X have until retirement?” (In Lethal Weapon and its ilk, this is a huge matter of discussion to the point of hilarity. In The Hurt Locker, they play it seriously and display it onscreen during the movie.)

It is much to The Hurt Locker’s credit that, until you have that epiphany moment, all these similarities seem invisible. It successfully makes all these cliches that are so common in action movies seem at home in a “serious,” legitimate movie about a recent historical event.

Danny Glover drops a bomb.

The explosions in particular bring this out – action movies have a hugely improbable frequency of explosions. The Hurt Locker is chock full of bombs and explosions. But The Hurt Locker is serious. It’s like watching one of those Learning Channel shows about human evolution and claiming you’re not doing to to be titillated by the scientific photographs of breasts. Except, you know, anybody buys it for a second and they don’t make fun of it on Office Space.

It reminds me a lot of Slumdog Millionaire, which is just a hop, skip and a jump from being a Li’l Rascals movie. There are a bazillion different disposable examples of the genre (band of outcast kids that includes a love triangle have mischievous adventures and grow up together), but which earned major legitimacy across the board and, dare I say it, duped its audience into thinking it was something they had not seen before while at the same time courting them with familiarity.

How do they both do it? The setting. They set their genre films and in places or circumstance that are difficult to portray on film because of cultural norms and precedent. They approach a difficult subject – extreme poverty in India or the American occupation in Iraq, and then they act out a movie in front of that cultural matte painting that is comfortable enough to make this strange place accessible to you.

People love to thrill at the exotic, and the self-same bourgeoisie who would scoff at awarding an Oscar to something like Lethal Weapon let their guard down if they sense the subject matter or movie is “important,” at which point they recognize that this genre of movie has redeeming qualities, that it works for a reason, and that the movie is really good.

To clarify, I’m not saying The Hurt Locker is bad or doesn’t deserve the praise it’s getting – I’m saying that other movies that are similar to it don’t get nearly as much praise because of superficial differences that trigger people’s prejudices. But I guess there’s justice, because the latter are the movies more people love and remember. To paraphrase Matthew 6, “Be not like the tentpoles auto-greenlit and raking it in at the box office, I tell you the truth, they are already repaid.”

So, yeah, The Hurt Locker is just like Lethal Weapon, except it takes out the villain and the comedy and replaces them with harrowing scenes of human suffering from the war in Iraq. Let’s look at what that means.

Harrowing.

I’m glad to have read this before Oscars night. Now, I no longer have to root for this movie to destroy Avatar. Now, I am completely indifferent to the whole process, much like my views on politics! fenzel, you’ve saved me from caring, which in its own way is one of the greatest gifts imaginable.

Addendum to your post- that staff psychologist, you know the one… he’s the same head shrink character from Lethal Weapon! They have a psychologist following around the team in both movies, for crying out loud!

Wow, this is weird. Carlos had this exact idea for an OTI piece but never got around to writing it. I guess The Hurt Locker really IS Lethal Weapon! (This is also how my dad refers to this movie.)

Also: While I wouldn’t say The Hurt Locker is a bad film, it clearly doesn’t deserve all the praise it’s getting. There. I said it so you don’t have to.

It is interesting to see the difference in the way Hollywood deals with madness. It seems that too often they take the view that one needs to just talk about it with a friend and suddenly its all betters. Having several good friends with some mental health problems, I can tell you that constant anxiety or depression don’t just go away because you get hugs. Sure, it helps, but I think since Lethal Weapon, people have come to recognize that there a physical nature for our moods and personalities, namely the neurotransmitters zooming around in our heads, sometimes developing in ways that aren’t our fault. I felt like some movies like Girl, Interrupted were shouting at some people to not be so sad all the time, to just suck it up, talk it out, and get over it. But can there really be mind over matter, when you mind fundamentally IS matter?

@mlawski and @fenzel: I think The Hurt Locker is getting all the praise it deserves. Possibly it deserves more. And yet I agree with Fenzel’s ultimate take – that by presenting the elements of a buddy cop film in a stylized, minimalist and serious way, The Hurt Locker gets more respect than earlier movies that have tread the same ground.

One could make the same case about several other critical darlings – No Country For Old Men vs. blaxploitation cinema, or There Will Be Blood vs. Dallas.

I think we can fill out the account of why “just entertainment” is such a crock, though this particular line of inquiry is not really germane to the point you’re trying to make. Not directly, anyway.

Even more often than it’s deployed by critics or diletantes to dismiss something they deem unworthy of consideration, it’s deployed by normal viewers (that is to say, viewers without any skin in the art-making game) to excuse the guilt they feel for preferring movies that aren’t preachy or generally considered “good for you.”

I think it’s a tragedy that we have to apologize for our pleasures, especially when the pleasure in question is a good story well told.

Just lost my comment to the void, but here’s the short version:

The Hurt Locker is clearly a well-made movie, and my problems with it are somewhat personal. I’m just over this type of character — see my comments on Stokes’s Overthinking Cowboy Bebop articles to see how much I want to slap Spike Spiegel across the face. At the risk of sounding political, the Renner character is so typically “American” — ooh, manly-man rugged individualist who is SO GOOD at his job that he can get away with being an asshole sociopath who gets everyone around him killed because he’s too much of a Real Man to work with others or seek psychological help to get over his death wish. It wouldn’t bother me so much if these types of characters weren’t always presented as super-cool anti-heroes instead of the nutjobs they so obviously are. It’s an action-adventure fantasy, that’s all.

Also(and maybe I shouldn’t get into this argument again), although I love many things that fall into the “just entertainment” category, can’t we agree at a certain point that Macbeth is better in some ways than Die Hard? (For the record, I love Die Hard, and I think Macbeth is incredibly entertaining.) Or, on the TV front, can’t we all agree that The Wire, which is both entertaining and “Important,” is in some ways superior to the best episodes of Burn Notice, which are incredibly entertaining but the polar opposite of “Important”?

@shana,

Well, MacBeth is just a script. Die Hard is a whole production. So you’d have to judge an entire production of MacBeth against Die Hard. I’ve seen a couple of movie and live productions of MacBeth, and while the script is better than the Die Hard script for a bunch of reasons, the productions were generally not as good as Die Hard.

I would say that if you want to point to the Wire being better than Burn Notice, you could find justifiable reasons to claim it, but I would caution against relying on its “importance.” The Wire does a lot of awesome things other than just be “important.” It isn’t just a bad history of Baltimore – it has a lot of artistry. Now, I haven’t seen Burn Notice, so I can’t make comparisons there, but I could do a pretty detailed comparison of The Wire and The Sheild that didn’t include at all whether one show was more “important” than the other.

I think using legitimacy or seriousness as the main criteria for quality is reductive. You don’t have to rely on it. Shakespeare certainly didn’t — his plays are funny, his characters are compelling and vivacious, and he’s not above telling dirty jokes. He didn’t have the luxury of patting himself on the back for being important, because Shakespeare made art people actually watched for a living and didn’t rely on criticial approval for his professional reward and fulfillment.

Maybe this comes from reading English literary criticism from over the centuries — watching a particular poet fall in and out of favor based on the intellectual fashion of the time. So much of the approval or legitimacy of the academy (or Academy, ‘natch) is just fashion — what people happen to think is important, what advances their own goals for themselves and their art form.

So, no, I’m not willing to concede that, say, Pilgrim’s Progress is better than Harold and Kumar go to White Castle, just because one of them is Worthy and Important the other one is contemporary, market-driven popular entertainment.

I agree with you on The Hurt Locker, by the way. The original article had a few more paragraphs bashing it, but they weren’t well thought out or necessary, and they were too relative to be worth pubilshing. The Hurt Locker is a very good movie that deserves praise, it’s more a matter of whether it deserves as much praise as it is getting or not — and at that point that’s kind of irrelevant; we have to see whether it wins the big Oscars or not, because I’m not sure everybody is on the same page about how much this movie is actually being praised. A lot of that is speculation about buzz. So, we’ll see how it turns out in the end.

@fenzel and the rest: Your comment makes a lot of sense. The fact is, I keep going back and forth on the “how do we judge art?” question. I’ve spent many hours of my life arguing that, yes, Jack Black’s Year One is just as much “art” as Hamlet. Art criticism is probably more subjective than any field on Earth, so it’s easy to make these kinds of arguments.

But I still don’t know. Part of me really wants to say, “Yes, definitively, 12 Angry Men is superior to The Blind Side, and anyone who disagrees is a big stupid.” And it’s not just because 12 Angry Men has superior acting or a tighter script — it’s because 12 Angry Men is ABOUT something and The Blind Side is just a series of Lifetime movie cliches. Why should movies be about something? I’m not saying that they have to be heavy-handed and preachy. I’m just saying that maybe those films that actually illuminate a truth about our real, lived lives are automatically a step up from films that operate in fantasy Hollywood-land. (And, no, this isn’t about genre: a piece of fantasy fiction like Pan’s Labyrinth can be considered more “true to life” than a theoretically “realistic” film like Valentine’s Day.)

Another problem with Macbeth: No Alan Rickman. Although Alan Rickman playing Macbeth in a movie version is definitely something I could get behind.

I think separating these two is more than just contextualizing. I don’t actually believe that “war is a drug” is a major thesis point of the film , I think its about much more than that, but that’s not what the topic is about so I’ll skip it.

Something my room mate mentioned was that the big thing for the Hurt Locker can be viewed through O’Brian’s The Things They Carried; which is not exactly entirely accurate about Vietnam, but is a metaphor that conveys the experiential truth of that conflict, the Hurt Locker is very similar. It shows a metaphor inside a certain context; whereas Lethal Weapon is a specific story entailing certain features. The Hurt Locker is too, to a certain degree but the difference my room mate discerned is that Lethal Weapon’s story is intrinsic whereas the Hurt Locker’s episodic nature was inherent not to describing the story but to describing certain features about the characters and the conflict. The Lethal Weapon is specifically structural whereas the Hurt Locker is more deconstructionist.

I think what separates The Hurt Locker from something like Generation Kill (the series form a book literally based on true events from the onset of the war) is that while the prior is hyper-realistic and the other is just realistic (because it is very close to the original source material just off form the actual events) is that the metaphor in the Hurt Locker is to convey an idea but that Generation Kill is to convey something that occurred and to show the “truth” in that thing, rather than the “idea” of Hurt Locker.

You’ve said a lot of interesting things here but ultimately I don’t think the similarity argument works. For me the part where the comparison really breaks down is this: Riggs is the classic Broken Hero, who’s aberrant behavior stems from some damage in his past, usually a loss, sometimes coupled with previously questionable behavior of his own. A Broken Hero is ultimately saved/redeemed by connection to a person or people around him. James’s aberrant behavior and his damage are pretty much one and the same and it’s made quite clear that any connections he might have to other people in his life are not going to make any difference.