This album is dedicated to all the teachers that told me I’d never amount to nothin’, to all the people that lived above the buildings that I was hustlin’ in front of that called the police on me when I was just tryin’ to make some money to feed my daughters, and all the ni—rs in the struggle, you know what I’m sayin’?

—Notorious B.I.G., “Juicy”

I just threw away a lifetime of guilt-free sex and floor seats for every sporting event in Madison Square Garden. So please, a little respect. For I am Costanza, Lord of the Idiots.

—Jason Alexander, Seinfeld

Every culture recognizes the hustler.

Greek mythology devotes as much praise to Odysseus – builder of the Trojan Horse; blinder of Polyphemus; the man who outwitted Circe and Proteus – as it does to the legendary warrior Achilles. The Native Americans of the Midwest venerated the mythical Coyote, trickster extraordinaire, while the Norse had Loki, who could even change his gender. You can find more classical fables, from Aesop to Jean de la Fontaine, that honor the cunning prey overcoming the mighty predator than vice versa. From the Monkey King of the Ming Dynasty to Anansi, spider-god of the Ashanti, every human society reveres cleverness and wit.

These mythological gods and heroes play a variety of roles. Anansi was a storyteller; Coyote, the creator of man and the Earth; Loki, a thorn in the side of Asgard. But they all share the similar Jungian archetype of the hustler: the underdog surviving on his wit.

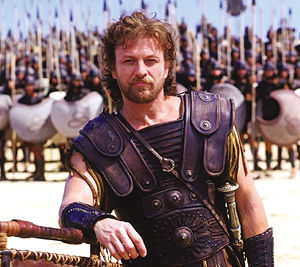

Smooth operator.

What is a hustler? To “hustle” is to hurry, to put forth the muscular effort to rush along. It comes from the same etymology as fast-talking someone: the smooth flow of street patter meant to overcome someone’s objections and trick them into something they wouldn’t agree to in quiet reflection. A hustler has to talk fast, move fast (to avoid trouble) and think fast (to come up with a clever story).

Note that hustling lives strictly in the province of the underdog: the poor, the common, the disadvantaged. If a king breaks a treaty and attacks a peaceful nation, he’s not hustling: he’s dishonorable. But if Haile Selassie breaks a treaty and attacks the warlords who outnumber him, he’s clever. Irwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox” whose tanks outmaneuvered Patton and Montgomery in WWII, was a hustler; Stalin, who sent Russians to die by the millions in defending Stalingrad, was not.

While the concept of “justice” has varied radically throughout history, every culture has had one. Everybody always has a notion of what somebody deserves. In feudal Europe, noble lords deserved the labor of their serfs, while the Church deserved homage from the nobility. In ancient times, when might made right, conquerors deserved the spoils of war.

But in every culture you found the hustler, who took more than he deserved.

The best summary of what makes a hustler probably comes from Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas:

After awhile, it got to be all normal. None of it seemed like crime. It was more like Henry was enterprising, and that he and the guys were making a few bucks hustling, while all the other guys were sitting on their asses, waiting for handouts. Our husbands weren’t brain surgeons, they were blue-collar guys. The only way they could make extra money, real extra money, was to go out and cut a few corners.

So we have a distinction between earning for a living – whether by labor or conquest – and hustling. And we have a distinction between the orthodox power of the mighty and the unorthodox hustling of the low. These distinctions are almost universal across the human race. They transcend barriers of language, skin color and history.

I’ve just fast-forwarded through ten thousand years of human history. Still with me? Good. Then, to quote the Notorious B.I.G., “turn the pages to 1993.”

Though there’s never a great time to be young, black and poor in America, the early 90s were particularly bad.

In March 1991, Rodney King was pulled over for speeding in Los Angeles and, after failing to cooperate with cops, subsequently beaten by four LAPD officers. Leaked footage of the beating sparked a public outcry, which boiled over into rioting once the four officers involved were acquitted of all charges. The rioting throughout the summer of 1992 led to over 50 deaths, more than 2000 injuries and $1,000,000,000 in damages. The resulting investigation exposed what many residents of Los Angeles had long suspected: endemic corruption and brutality within the LAPD.

Over on the East Coast, the crack epidemic had just come off its worst years. Though violence was at a temporary low, the introduction of crack – a cheap and potent form of cocaine – had sparked a massive rise in urban gangs and violence. These gangs, and the drug problem, did not vanish over night. The generations weaned on gang life had now come of age. Some branched into traditional gang mainstays such as extortion and robbery; others into different drugs, like heroin or cocaine. But the “official” end of the crack epidemic did not mean the end of urban crime.

Out of this culture came gangsta rap. The term “rap” comes from the Beat Generation, meaning to talk in a laid back, informal manner. Rapping spread through the inner cities as a way to showcase cleverness; Muhammad Ali was particularly famous for his raps. But the Sugar Hill Gang was the first group to make rapping famous as a form of music, by looping a bass beat (“Good Times”) and rapping over it.

The Sugar Hill Gang set the tone early on: rap music was supposed to be true to life. It’s about things the listener can relate to (“have you ever went over to a friend’s house to eat,” etc). But it didn’t take long for voices agitating for social change to use rap as a medium for harsher truths. I could pick from several examples, but “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five is probably the best example.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dShcXDacNXM

Rap grew edgier over the years; see 2 Live Crew or the Geto Boys. It also improved in artistry, with Run DMC and the Beastie Boys being leaders. But it wasn’t until the early 90s that we saw the beginnings of what was later called gangsta. If early rap was about how the folks in the projects lived, gangsta rap was about how the hustlers lived.

Gangsta rap might not have taken off as it did were it not for two factors: the Biggie / Tupac feud, and MTV.

First, while it’s unfair to credit Christopher Wallace (a/k/a The Notorious B.I.G., Biggie Smalls, or the Black Frank White) and Tupac Shakur (a/k/a 2Pac or Makavelli) with the genesis of gangsta rap, they became its public face. As high-profile performers backed by ambitious studios, they went from friends to rivals to enemies in a few short years. The feud between East Coast and West Coast rappers was a synecdoche for gangsta rap itself: the opulence, the artistry, the boasting, the implied and actual violence.

And it didn’t hurt that they were both damn good.

Second, while gangsta wasn’t the first rap to get played on MTV by a long stretch, gangsta seemed uniquely suited to the medium. By the 90s, producers had long realized that a music video was no longer an added feature for a song but an essential consideration. Videos went from being an afterthought (consider “Video Killed The Radio Star”) to a vanguard (consider “Justify My Love”). Style and substance have always kept an uneasy truce in pop music – and now visual style was winning.

Into this battlefield came a style of rap that boasted about luxury. Gold rings on every finger and platinum chains around the neck. Packed nightclubs, dark save for recessed lighting under the counters and strobes cutting through cigar smoke. Icy bottles of ludicrously expensive champagne. Women in sprayed-on dresses and bikinis, rubbing themselves with vacant stares.

None of this was new imagery, of course. King of New York, Goodfellas and Scarface had glamorized the wealth that came from drug dealing for years. But gangsta rap was the first genre to put that imagery in service of its music. MTV, a channel that thrived on delivering desirable imagery to teenagers and young adults, ate it up with both hands.

It’s no accident that gansta rap ascended in the 90s. Looking back, it’s clear that gangsta was an idea whose time had come.

Beautiful

After reading this article I went to a coffee shop where they were playing “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.” Zero Mostel might be the ultimate hustler, between that role and his role as Max Byalistock in “The Producers.” In both roles he plays a down-on-his-luck shmuck who isn’t very bright, but manages to achieve his dreams by manipulating and lying to everyone around him, and yet we can’t help but root for him!

The schmuck (or shlemiel) is one of the oldest comic stereotypes.