[If anyone was hoping for another Cowboy Bebop post, don’t worry – I haven’t abandoned the series. But Choose Your Own Adventure came up on one of the podcasts a little while back, and I wanted to get this finished while it was still on my mind.]

In a few hundred years, when people get around to writing a really definitive history of avant-garde literature in the 20th century, I hope they pay enough attention to Choose Your Own Adventure.

I’m not even slightly kidding. The Choose Your Own Adventure books (and the other gamebook series – Time Machine, Tunnels and Trolls, Fighting Fantasy, and so on) are a far more successful challenge to our received notions of what “reading” is about than any modernist novel I’ve encountered.

And everyone read Choose Your Own Adventure back in the day. Two hundred and fifty million copies sold between 1979 and 1998, according to Wikipedia, and in 38 languages. Astonishing. I have no idea how to figure out how many copies of Finnegan’s Wake were sold during the same period, but I’m guessing less. And while I hear you saying already that selling a lot of copies doesn’t actually make a literary work successful, it does matter in this case. A challenge to standard narrative that doesn’t reach a mass audience is not really a challenge at all. It doesn’t mean the niche stuff isn’t good or important, but to be a really viable alternative it needs to be, uh, viable.

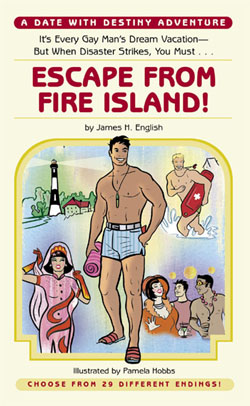

Anyway, the CYOA books would have been pretty radical even if they hadn’t been lucrative. The earliest gamebooks came out of the French experimental literature collective Oulipo: in 1967, Raymond Queneau produced a short story in this format which you can still read here, assuming you speak French. And the idea was in the air earlier than that… “One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with,” Flann O’Brien writes in At Swim-Two-Birds, which sure enough has three beginnings and three endings, if you’re not too careful about how you define the concept. But I’m not here to try to rescue the artistic purity of reader-driven-narrative from servitude in the brothels of capitalism by pointing out that “serious” intellectuals did it first. I’m here to talk about the CYOA books themselves, which deserve to be remembered for their own merits. (But before we leave the topic of brothels, let me just point out that there are apparently a LOT of “adult” CYOA titles out there. I knew about the one I linked to from working in a bookstore, but while googling it I found out that there are, like, way, waaaaay more than I expected. And while I don’t get the feeling that all of these are actually pornographic, they’re all selling themselves on a winking hint of sexuality coupled with a healthy (unhealthy?) ladle of nostalgia, sort of like a “Sexy Smurfette” Halloween costume. Gross. But then, the cover art on Escape From Fire Island is just perfect. And I bet no other book has ever had, or ever will have, the Amazon tags “Champagne Toast,” “The Meat Rack,” “lifeguard station,” “zombie epidemic,” and “The Golden Girls,” making Escape From Fire Island another one for the ‘ol ‘Unsurpassed and Unsurpassable’ file.

Anyway, the CYOA books would have been pretty radical even if they hadn’t been lucrative. The earliest gamebooks came out of the French experimental literature collective Oulipo: in 1967, Raymond Queneau produced a short story in this format which you can still read here, assuming you speak French. And the idea was in the air earlier than that… “One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with,” Flann O’Brien writes in At Swim-Two-Birds, which sure enough has three beginnings and three endings, if you’re not too careful about how you define the concept. But I’m not here to try to rescue the artistic purity of reader-driven-narrative from servitude in the brothels of capitalism by pointing out that “serious” intellectuals did it first. I’m here to talk about the CYOA books themselves, which deserve to be remembered for their own merits. (But before we leave the topic of brothels, let me just point out that there are apparently a LOT of “adult” CYOA titles out there. I knew about the one I linked to from working in a bookstore, but while googling it I found out that there are, like, way, waaaaay more than I expected. And while I don’t get the feeling that all of these are actually pornographic, they’re all selling themselves on a winking hint of sexuality coupled with a healthy (unhealthy?) ladle of nostalgia, sort of like a “Sexy Smurfette” Halloween costume. Gross. But then, the cover art on Escape From Fire Island is just perfect. And I bet no other book has ever had, or ever will have, the Amazon tags “Champagne Toast,” “The Meat Rack,” “lifeguard station,” “zombie epidemic,” and “The Golden Girls,” making Escape From Fire Island another one for the ‘ol ‘Unsurpassed and Unsurpassable’ file.

So, the radical things about Choose Your Own Adventure books. (Or at least apparently radical. We’ll get back to that.)

- First of all, although each book has a solitary beginning, they do have multiple endings, and in a way that surpasses anything Flann O’Brian came up with. For all that At Swim-Two-Birds claims to have multiple endings, they appear in a fixed order, and even a perverse reader who purposely tackles them out of order will read one of them last, making that one the “real” ending. CYOA books, on the other hand, may have dozens of endings spaced throughout the book, and each is an actual, definitive, end. (Or not. More on that later.)

- Second, to increase universal appeal, the protagonist (that is, “You”) has no gender, no race, no religion, no sexual orientation (21st century erotic repackagings of the concept notwithstanding). No political opinions, no particular skill set… a total blank slate. I do seem to recall that the protagonist was usually described as a child (the books being marketed to children), but that’s about it. Eat your heart out, The Man Without Qualities.

- Third, the reader drives the action: as the title of the series suggests, you get to choose how the story develops. Just like you can choose whether or not to read the rest of this post.

But like I implied, all of these “radical” elements can be undermined. The last has been pretty well debunked by the more cerebral class of video-game critics. If you’re asked a multiple choice question with only one answer, do you have a choice? No. How about only two answers, both planned out for you ahead of time? Does the situation really change with three answers, or a dozen? The illusion of choice becomes more and more elaborate, but it doesn’t ever become freedom: a cage is a cage, no matter how large it is. By the same token, while the unmarked “You” of the narration allows readers to insert themselves, there’s no room to try out other identities. I mean, I could read The Cave Of Time while thinking of “You” as a Armenian bootblack, but it wouldn’t have any effect. You’re never going to get a choice that says “If the smell of fresh leather triggers a flashback to your father’s workshop in Yerevan, turn to page 36.” And as for the multiple endings, well…

As defined by the “rules” of the book, when you come across the words THE END you have no choice but to head all the way back to the beginning of the book and start again. But in fact you did have a choice – when you came across a fork, you could fold down the page or stick your finger in the book to mark your place, so that if one branch of the decision tree proved fatal or boring, you could simply backtrack. As a result, a bad ending was only rarely a “real” ending. Even a moderately good one was only temporary. So if the ending of the book simply as “the last page you read before you return it to your middle school library,” then there really was only one, just like there’s only one real ending to At Swim-Two-Birds. I don’t know about you, but I read these books in search of the best ending, and only considered the book as “ended” when I found it.

That’s quite a statement, though, because it implies that the “real” ending of a book is defined by the reading habits of the audience. And this brings up the more fundamental innovation of CYOA. We read normal books to be entertained. We read CYOA books to win. All the enjoyment we get along the way is just incidental to the triumph of securing the happy ending. Even a real page turner of a book – by which I mean a book in which most of our enjoyment comes learning more about the plot – doesn’t give us the same sense of accomplishment, of winning, that I got as a child from locating the good end of a CYOA. Furthermore, our reading habits can change. If I were to go back and read one of them today, for instance (and I may or may not have recently done this — you decide!), I’d be a lot less caught up with finding the good ending, and a lot more interested in finding all the endings, i.e. finishing the entire book. Which means that the “real” ending – using the definition of ending I gave above – would just be the ending that I got to last. Depending on how the book is structured, the “real” ending might not even be an ending at all. Sometimes there was more than one way to arrive at a given game-over, so my last thoughts before putting the book down might be something like “Ah, I see where this is going, after this I get eaten by the shark again. Okay.”

So here’s a question for you: who’s reading the book right? Old Stokes or Young Stokes? Earlier I mentioned the “rules” of the book, and while neither of us were really following them precisely, Young Stokes might be closer to the spirit of the thing. Trying to “win” at the book isn’t perverse – it’s what you’re supposed to do. You’re supposed to identify with the character… sadistically marching him/her into death after gruesome death just for the experience is more than a little ghoulish. But I think Old Stokes is getting more out of the experience. As a child, I was too focused on the end benefit. I wanted so much to find a happy ending that I stopped caring about the process of reading the book. Sometimes it would get to the point where I would actually STOP READING the text of the pages, skipping directly to the choices at the bottom so that I could navigate through the book more quickly. Sometimes I would flip through the book at random until I found the good end, just to satisfy my curiosity, but I still wouldn’t consider myself to have “finished” it until I could find my way on my own. Navigating the decision tree was more important, by far, then the content of its branches. And that might be a more severe violation of the “rules” of the book. You are still meant to actually read the thing, aren’t you?

Or maybe the rules, like the ending, change according to the reader. And this is where CYOA really shines as an alternative to classical narrative. Think about a standard novel. There are many ways to interpret it – that is, many things to get out of it – but there’s only one acceptable way to read it: seriously, carefully, reverently. And reading in this sense implies a few more things. There’s a principal of ontological unity: if you read halfway through a book before getting bored and stopping, then you haven’t really “read” the book, right? There’s also a principal of aesthetic unity: if you soldier through to the end out of sheer bloody-mindedness, then you’ve read it… but you didn’t really “like” the book, no matter how much you enjoyed the first half. Right? And there’s an implied moral duty to the author. Reading the book halfassedly – taking the chapters out of order, skimming the parts you don’t like, doodling sarcastic comments in the margins, MST3K style – is usually thought of as some kind of betrayal of the author, or at the very least as extremely rude. There’s no rhyme or reason to any of this – especially because the last one still applies even when the author is dead – but these are the unwritten rules of reading, and they’re as true for “daring” modern fiction as they are for the stodgiest 19th century literature. And they apply just as well to commercial cheese: when I was reading the Da Vinci code, I cheerfully slagged it off to anyone who’d listen to me complain, but I still read the whole thing, in order, from beginning to end.

They don’t apply to CYOA books, though. Not because CYOA books offer some kind of radical freedom to the reader – like I said before, you don’t really control the narrative when all the choices are laid out for you – but because the new rules that you’re presented with are so arbitrary, so confining, that you begin to discard them the minute you begin to play the game. There’s even one CYOA book, UFO 54-40, that lampshades this: unlike most books in the series, it only has one ending, and what’s more the ending is hermetically sealed off from the rest of the book. (!) You can’t get there by following the rules: either you skip to the page, or you don’t read it at all.

Now, the author was trying to make a point about thinking outside the box, telling you that you can’t win by following the rules. The message I receive, though, is that the whole idea of “winning” a book, of rules for reading, is meaningless. You win at reading in that you enjoy it: within this one limited corner of human experience, the only rule is the rule of pleasure. So let’s go ahead and mark our place with a finger. Let’s stop reading when the book gets dull. Let’s write snarky comments in the margins. Let’s imagine that the main character of a CYOA book is an Armenian bootblack. We can even imagine that the main character of Hamlet is an Armenian bootblack if you’ve a mind to – it’s not my idea of a good time, but if it floats your boat I’m willing to play along. This doesn’t mean that dense literary tomes don’t have value, nor that ponderous analysis isn’t a valid form of enjoyment in its own right. (The amount of completely unpaid time we all spend writing for this website, it had better damn well be a valid form of enjoyment.)

By the way, although Choose Your Own Adventure‘s little cultural moment has already come and gone, those books were more influential than you might think (or maybe just prescient). The “branching trees” model has become absolutely standard for video game plots, although the mechanism for triggering one branch or another is rarely as simple as “turn to page twelve.” And the model of reader experience created by CYOA is even more widespread in our culture – not the model they intended, where the reader navigates a series of linear narratives, but the model that readers actually followed, where you mark your place with your finger, flip around at random, and skim through the text itself on your way to the (sometimes unattainable) perfect end-benefit of your reading experience, only to suddenly look up and realize that four hours have passed. I’m hoping I’ve constructed the metaphor well enough for you to see the parallel to the process of surfing the web. After all, what is your browser history but an expertly managed stack of fingers marking your place? What is a hyperlink but an instruction to turn to page 15 (or to DNS code 74.126.19.21, as the case may be). And what is wikipedia but “Edit Your Own Encyclopedia?”

Which reminds me: when they write that history of the 20th century literary avant-garde, I hope they pay enough attention to the Internet.

——

What do you do?

To read a deeply fascinating essay about the information structure of specific Choose Your Own Adventure books, turn to page 12 click here. (This essay is fantastic: it’s full of insight, and the author managed – amazingly enough – to use the order of the story segments in the published books to deduce aspects of the authors’ creative processes. His charts are jaw-droppingly beautiful.)

To read a hilarious, 4th-wall-shattering deconstruction of a Choose Your Own Adventure Book, turn to page 23 download this pdf from the mad geniuses over at Kingdom Of Loathing, who know from 4th-wall-shattering deconstructions. Their artwork is not particularly jaw-dropping, but it has its charm.

To purchase a copy of Pierre Bayard’s fantastic book-length essay How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, which although I didn’t bring it up directly was definitely part of my thought process as I wrote this, turn to page 9 click this here amazon link so we can get our sweet two cents.

To post a comment, turn to page 11 just go ahead and post a comment.

I used to read CYOA’s avidly, and then expanded to Fighting Fantasy’s in my early teens. Once the internet came into fruition, I realized I could get more of these books through Ebay, and started collecting as many FF books as possible(some as far away as Australia). I am currently within having all of the Steve Jackson/Ian Livingston books, only missing a couple of the real high numbered ones.

I had a plan a few years ago where I was going to roll one character, and go through each book in order, keeping any skills, stats, and abilities I could. I would only use a skill if it was relevant to the book (No using high science in the Modern-era book). I don’t recall what I would do if I died, if I would start the book over, or start at the beginning, but thinking about it now, I think I would have made me reset to start of the book I died in.

I got about 2 or 3 books in before I lost my steam, sadly. I thought at the time, and now fondly looking back now at it, it would be a really interesting experiment, and would think the character sheet would be Huge(and a mess of rubber eraser) at the end of it all.

Had anyone else had an ambitious project as this? Also, did people tend to use a piece of paper, or jump back to the character sheet in the book???

Some of my improv friends made a cool Choose Your Own Adventure video series — also an increasingly popular form of exploration of the genre:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-D0Pb1o1-0

I wanted to leave a thoughtful and intelligent comment other than “Duuuude, Choose Your Own Adventure RULED!!” However…….Duuuuuuuuuude Choose Your Own Adventure RULED!!!!

I may be wrong, but doesn’t Tom Hanks say something like, “It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure,” while designing the video game in _Big_?

Interesting dichotomy in reading-styles between your older and younger selves- one I experienced in the inverse, actually (and oddly enough). I don’t really think there’s a “right” way to read them applicable to every one, too. I think it depends on what is expected by, not from, the reader. If they want to “win,” if they want to see how they’d do against those restrictions, if they want to get as many possibilities as they can- so long as they reach whatever goal (within or without the story) they desire, it’s valid and valuable. I think that’s one of the beauties of entertainment in general, yes, but specifically literature in all its forms. There isn’t a “right” way to read something, not when focused on what a person “gets out of it.” Respect toward an author isn’t necessary for one to be entertained (or NOT entertained, either), and once the words are in the hands of the reader, it becomes theirs to do with as they wish- the author has no more agency in the matter, or can at least lose any agency if the reader desires it.

::end rant::

“Space Patrol.” Does anybody remember this particular installment of the series?

http://ktarini.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/cyoa0222.jpg

My mind immediately went to this cover. I can’t remember anything at all about the story, but I do remember that this was one of my first experiences with science fiction imagery. I think I doodled about 400 different versions of the SREV III and that dude with the laser gun in the second grade.

Also on the topic of CYOA cover art:

http://www.somethingawful.com/d/comedy-goldmine/choose-your-own.php

I also came upon this gem while googling “choose your own adventure”: “Master of Tae Kwon Do.”

http://www.gamebooks.org/gallery/cyoa102.jpg

This does somewhat contradict Jordan’s 2nd point about the universality of the protagonist, “you.” In this case, it’s clearly a white male who’s beating up those, um, North Korean ninjas.

Which, by the way, is another example of whitey keeping the yellow man down. I say that only half jokingly; though I can’t properly cite this off the top of my head, I seem to recall there being a common trope among western-produced martial arts movies of a lone white guy beating up hordes of screaming Asian dudes.

Sigh. Leave it to the token OTI minority to bring race into a discussion on Choose Your Own Adventure.

I’m glad you brought up UFO 54-40, which in many ways was the best book of the series.

I think they did the pure scifi titles much better than the realistic stuff, though I’m not sure why. I also remember a good version where the premise was that the Earth was hollow and there was a small black hole at the center.

I also was fascinated by the series during my teenage years. After reading the Cave of Time, I drew a decision chart, though I had no idea then that it was called that, that looked like a cave but tracked all the different narratives in the book. Since in that book different narratives often flowed into each other than flowed out again, the drawing wound up looking like a map of an actual cave system.

My reading preference has always been to read the book the first time, making decisions as close as possible to the ones I would make in that situation, and treat the resulting ending as the “real” ending, even though the first ending I came too usually involved death in some horrible manner. Then I would back up and explore the alternative endings.

The books however suffered from what I call the “red door, green door” syndrome, there were too many choices similar to a situation where you had to choose whether to go into a red door or green door, with no other information, and with the red door the story continued with you driving off in the car left on the other side of the door, and if you choose the green door you got eaten by a tiger. But with the better stories it was possible to pick up a few pointers on how to make decisions and on survival skills, for example swimming back to the shore at a 45 angle when you get caught in a strong current, or avoiding cafes in Middle Eastern cities likely to be bombed, both of which featured in choices presented in some of the books.

@Lee – Good catch! I wonder, though, whether that actually comes up in the story, or whether it’s just the artwork. I remember the text of those books being neutral — although as a white male, it’s entirely possible that I just didn’t notice… privilege is insidious that way — but If you flip around through the cover gallery, you’ll find that the protagonist figure is usually a guy and always, always white.

There do seem to be a number of stories about an Anglo-American youth going on a mysteeerious journey into the lands of some dusky-skinned people or other. So that’s not great.

@Ed –

I like your description of “Red Door, Green Door” syndrome. That’s the kind of thing that I hated, hated as a child, but today I find kind of charming.

Another interesting point. Some of the books clearly tried to form an internally consistent world that you could explore, so that, for instance, if there were zombies inside the barn in one story thread, there would be zombies in the barn in all story threads. But others were less consistent. Whether there were zombies in the barn or not might depend on what story fork you were on, meaning more practically that your decision to go swimming instead of hiking at the very beginning of the book had apparently caused a zombie apocalypse. I remember one called Prisoner of the Ant People that combined this with the “Red Door, Green Door” syndrome to bewildering effect. At one point, while trying to escape the ants, you found yourself trapped in a room with three totally random objects. There was a ray gun, I think, and maybe a lantern, and – this one is stamped into my brain, for some reason – a sword blade without a hilt. Your only choices were to pick up one of these three items, and there nothing anywhere else in the book to explain what they might do.

Anyway, each of these led directly to an ending. But the endings were completely incompatible. I don’t remember the specifics, but one object definitely led to a scenario where it turned out that the ants were good all along, and another led to a scenario where you singlehandedly burned every ant on the planet to death. And I think choosing the hiltless sword made you transcend to a higher plane of existence. Trippy stuff.

Great post, personally I always read through as myself, then found the “good” ending, then meticulously read every other ending like the neurotic child my psychiatrists somehow didn’t pick up on at the time.

DEFINATELY looking forward to the next Cowboy Bebop by the way, I’ve already rewatched the series twice because of your posts and the specific dvds in said posts both before and after reading them.

I am a Bebop junkie.

Short time reader, first time poster…

I just had to comment on this article, as I was also in the prime “80’s child” age group to really enjoy these books as a kid. I still remember my favorite story, although the title escapes me. Basically the premise was that you had this rare genetic anomoly that allowed you to be extremely talented at any one thing (for example, you could choose to be a brilliant scientist or a world-class tennis player).

Looking back, even though I don’t remember thinking this at the time, I am surprised that “you” as the character would die some horrible death so often. It seems that it would be a little traumatizing. Although it was neat how they usually wouldn’t come out and say “you’re dead”, but allude to some disaster or inescapable situation before ending (e.g. “the three-headed monster approaches you with mouths wide open showing rows of razor-sharp teeth, as the door behind you locks shut. THE END”

After reading this article, I discovered that many of the CYOA books are, in fact, available for download on the Kindle. At $5.50 or so a piece, it’s a pretty cheap run down nostalgia lane. Arguably, it’s a much better medium for the books than physical books are:

http://www.amazon.com/Choose-Your-Adventure-Books-Kindle/lm/R1109XFERTWOQ4/ref=cm_lmt_srch_f_1_rsrsrs1

@Tom: that’s fascinating, and it also raises some interesting questions: did they implement hyperlinks to allow you to jump straight to the indicated page? And more importantly, how does not being able to hold your finger to mark your place change the experience?

Most importantly: will they be available for the Apple tablet? ;-)

@Jeff: I believe the one you’re referring to is “You Are A Superstar.”

And yeah, a remarkable number of deaths for children’s literature, especially considering they were all notionally your death. I remember getting terrified to the point of nightmares at Space Vampire.

@lee: I’ll read one this weekend and report back. As for your second question, there’s already an iPhone/iPod Touch Kindle app – wouldn’t they naturally have one for the Apple tablet?

So, my experience with CYOA is from the library at the Catholic school I went to for first grade, where I was not allowed to check out books from the 4th grade shelf, even though they were the same level books which I was already reading at home. But the 1st grade shelf was chock full of CYOA. Maybe those nuns were promoting more advanced literary choices than I thought! I certainly had fun reading them. Also, my favorite Edward Gorey book is The Raging Tide/The Black Doll’s Imbroglio. If you choose turnips…

Having gone through one of the books on the Kindle (The Abominable Snowman, Book #1), the experience is certainly different from what I recall. Instead of going to a page, you get a “click here” message. If you try to hit “Next Page” or “Previous Page,” you get an error message telling you to go back and make a choice, but if you keep going you can advance to another story. What you can’t do is go backwards on the decision tree, which is more than occasionally frustrating (especially because the instructions claim that you can, in fact, do so). The overall effect is to make it feel even more like an early text-based RPG than it did when it was in book form.

I did notice another symptom of the “Green Door/Red Door” syndrome, where peripheral characters are either good or bad depending on a previous, totally unrelated choice.

Overall, I enjoyed the experience, but I probably won’t buy any more of them. For less than six bucks, though, it’s a fairly enjoyable way to kill 30-60 minutes.

@Tom – That’s VERY interesting! Thanks for the report. So, to me at least, the Kindle version kills the most interesting thing about these books, in that you have to actually obey the rules of the book all the way through, rather than alternating between “playing fair” and taking a more unfocused, hedonistic approach to the text. The comparison to text based rpgs is very apt – the essay on samizdat.cc that I linked to points out that the rise of gamebooks as a commercial phenomenon is pretty much contemporaneous with the rise of that kind of computer game. And like you say, the big difference is that you have to play the computer version by the rules: you can’t just skip to the end of Zork. (Well, with some of those old games you actually could open up the resource files as text documents and page around through the descriptions at your leisure. But it took a bit more initiative.)

I wonder how the kindle version takes care of the “hidden” pages of UFO 54-40? … Ah. They just didn’t release that one for the kindle. Nice.

Inevitable march of capitalism and technology: 1.

Artistic innovation: 0.