"Mmm...macroeconomics"

[Special thanks to Stokes for coming up with the concept for this D’OHverthinking It post. – Lee]

It’s often said that the Simpsons are intended to be an iconic representation of typical lower-middle class Americans. The father works a semi-skilled blue collar job, and they own a home and two cars, but they’re always a little short on money, and their financial problems have often been used as major and minor plot points in the series.

But “The Simpsons” is an episodic TV show–that is, plot elements typically don’t carry over into future episodes. Granted, there are some exceptions (the death of Maude Flanders being a notable one), but for the most part, problems that arise in one episode are resolved in that episode, and that’s that.

The same holds true for the Simpsons’ financial problems. Someone in the family (usually Homer, but often Marge) makes an unsound financial decision, pays the consequences of that decision for the duration of the episode, and is finally saved from that situation through implausible but humorous plot devices. Problem solved. Subsequent episodes may mention other specific or general financial difficulties, but never the lasting ramifications of past mistakes or hardships.

Sounds familiar? Like how for the last twenty years, consumers and individuals kept borrowing money to solve problems until the credit stopped flowing?

You may be asking yourself: “Surely you can’t be serious in suggesting that the Simpsons’ episodic and ephemeral fiduciary actions actually influenced American consumer behavior to the point of causing systemic collapse.” But consider the complex relationship between a piece of art like “The Simpsons” and the real world its audience inhabits. A show like “The Simpsons” both satirizes and sanitizes the poor fiscal habits of irresponsible middle class Americans. Those same middle-class Americans who comprise the show’s audience are attracted to the show, partly for this reason. They grow more and more accustomed to this sort of behavior, and worst of all, its lack of real consequences.

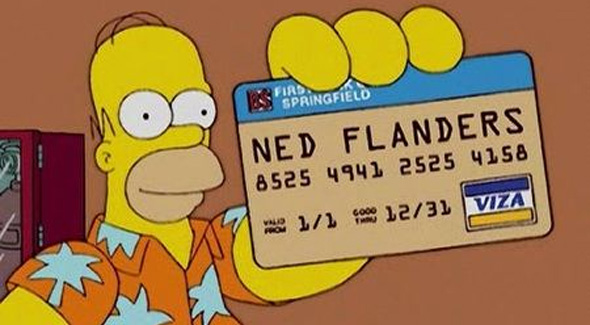

The Flanders Bailout Package

In small yet significant ways, this changes real-life attitudes, which changes real life behaviors. The show turns back to its audience for the source of its satire. The cycle not only repeats itself, it amplifies itself with each iteration. Think I’m overstating the impact of television on our culture? Look no further than this show’s impact on our language and try to tell me that TV doesn’t affect us in significant ways.

Twenty years of “The Simpsons” has led America down the path of high spending, massive debt, and anemic saving without any sense of real consequence.

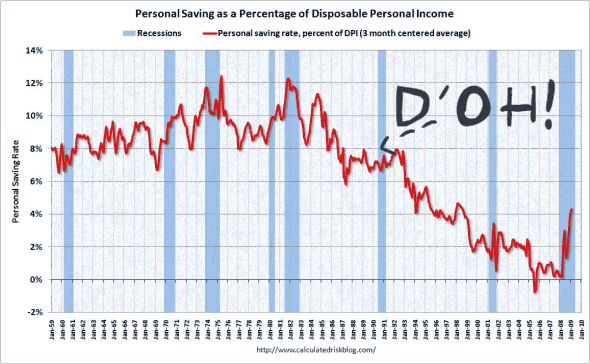

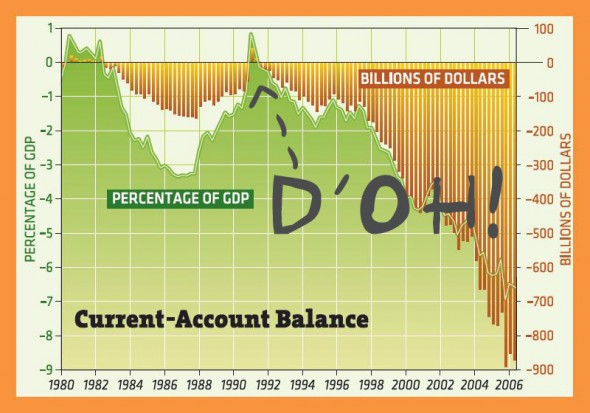

I say this partly in jest. But take a look at these economic trends over the last twenty years “The Simpsons” has been on the air:

When did America’s household income-to-debt ratio start to fall off the cliff? Almost twenty years ago:

When did America’s trade deficit (current-account balance) start to fall through the floor? Almost twenty years ago:

Yeah, yeah, correlation does not equal causation, I know. But even if you discard the causal link between “The Simpsons” and the economy (I wouldn’t blame you if you did), it’s hard to ignore the eery parallels between the rise in popularity of this show and the consumer behavior depicted within and the sea changes in our economy over the same time.

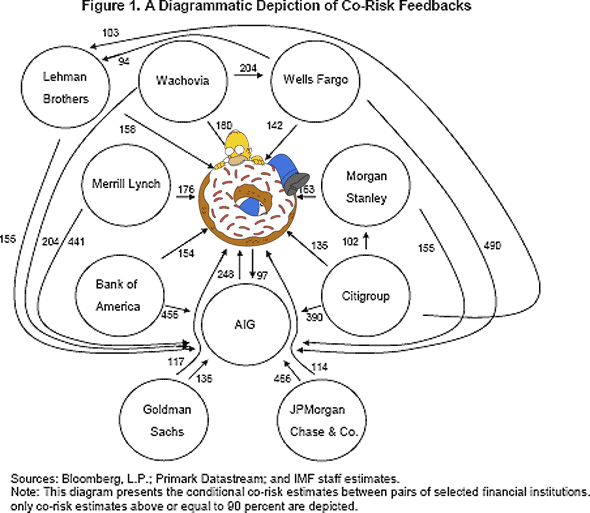

And if you’re still not convinced, well, see what was at the nexus of systemic risk in our financial system right before the crash:

"Mmm...systemic risk"

I used to have this same debate with myself quite often on another topic – the correlation between the fall of the so-called “traditional family” in our country and the explosion of shows such as Kate & Allie, My Two Dads, Full House, Out of this World, Blossom, etc etc etc. It was pretty evident to me as a kid that, while pretty much all of my friends’ parents were divorcing, the number of shows with divorced, widowed, separated or unmarried parents was rising exponentially, and shows like The Cosby Show and Family Ties were fading into the background. Was television oddly prescient, or did these shows come into the fore precisely to make people feel better about their situations? Or, as your article seems to imply, did these shows actually have a causal effect (perhaps parents in unhealthy relationships saw these shows as vindication that they *could* make it on their own, and gave them societal “permission” to try?)

It’s a similar conundrum to the one you present here. It seems more than a little likely that causation is at play here, but in which direction? Does art imitate life, or life imitate art? Or is it a little from column A, a little from column B?

I would add that, in addition to seeing no negative consequences, we also never see the Simpsons decide NOT to buy something. (Well, maybe once: there’s an episode where Homer has been saving up to buy an air conditioner, but Lisa’s sax gets broken so he buys a new sax and foregoes the AC.) Generally they buy whatever they want, travel the world, etc. For every episode where financial irresponsibility drives the plot and is swept under the rug at the last minute, there’s a dozen where equally irresponsible actions are taken without even short-term consequences. The family throws a massive BBQ party complete with a whole roast pig. Bart and Lisa enroll in a private military school (or fat camp, or ballet lessons, etc. etc. etc.). The City of New York issues Homer several dozen parking tickets, compounded with a “

smalllarge lateness penalty.” And they pay for all of it somehow. The most egregious example is the episode “Marge Simpson in: Screaming Yellow Honkers,” where Homer impulse-buys an SUV. The episode is basically about road rage, and although I’d have to watch it again I don’t think the financial impact of the purchase is even mentioned.When you combine this sort of thing with the episodes that do focus on the family’s finances, it gets even uglier. America’s problem with credit card debt is partially the result of aspirational spending: people who self-identify as middle class buy their way into a lifestyle that they can’t actually afford. No one wants to self-identify as poor, and with the Simpsons floating right on the very bottom edge of middle class respectability, this means that most Americans will think of themselves as better-off financially than the Simpsons. This can lead to a vicious circle: “I want an SUV. Homer Simpson can afford an SUV (as demonstrated by episode X, where he buys one without consequence). But Homer Simpson is on the brink of financial collapse (as demonstrated by episode Y). Because I have not quadruple-mortgaged my house, I am better off than Homer Simpson, and because I am better off than Homer Simpson, I too can afford this SUV. And the good people at Capitol One must agree with me, or they wouldn’t be offering me an adjustable rate on my car loan! Adjustable things are always better – this is basically the barcalounger of financial instruments, right? – and the offer says ‘act now,’ so I’d better not think this through. After all, What Would Homer Do?”

I remember an Simpsons episode where they buy an elephant. And they have to get rid of it because they can’t afford to feed it. So there may be one counterexample.

Also, the “everything gets wrapped up in a half hour episode” is a long standing US sitcom tradition, which I think has something to do with syndication.

Congrats on writing our 800th post, Mark. I’m using the OTI credit card to get you a granite yacht.

the elephant episode:

Bart wins a radio contest and they offer him cash or A FULL GROWN AFRICAN ELEPHANT. Homer and Marge wants him to take the money, but their 10 year old kid really wants A FULL GROWN AFRICAN ELEPHANT, so they say “yeah, whatever, get the elephant, we don’t see how this can possibly go wrong”. Soon, it becomes evident that keeping A FULL GROWN AFRICAN ELEPHANT as a pet can be quite expensive, so they try to get a profit off him, but their marketing/bussines strategy proves unviable and they end up buried in debt. Someone offers to buy the FULL GROWN AFRICAN ELEPHANT, but they just give it away for free to the first wildlife reserve they see. THE END.

AAnd what makes this story even worse is knowing that just a couple seasons before that, Homer had to get a high interest loan and a second job at the local convenience store to buy and maintain a pony, just because “his daughter stopped loving him”.

Some people just never learn.

I love the later episode where the subject of elephants comes up, and we get this exchange:

Bart: I wish I had an elephant.

Lisa: You did have an elephant. His name was Stampy. You loved him.

Bart: [wistful] Oh yeah…

I remember Marge mentioning in a somewhat recent episode that she always keeps a good bit of money tucked away to compensate for Homer’s wacky antics. This of course would never cover everything on the show, but it helps somewhat in explaining why the Simpsons themselves aren’t losing their house.

@Matt, funny you should mention the Simpsons losing their house. An episode from this season actually had the Simpsons getting their house foreclosed on. I thought about including it in the article but wound up not doing so A) because it didn’t exactly fit and B) because it was a laughably weak attempt at making the Simpsons reflect current economic conditions.

Nevertheless, let’s unpack it in the context of the argument while we’re on the subject.

SPOILERS BELOW:

The episode basically runs like this: Homer throws a lavish Mardi Gras party that was funded by a home equity loan (note: this is far from the first time that Homer has borrowed money against the house; in one episode he’s explicitly shown to have 4 mortgages). The Simpsons can’t make the monthly mortgage payments and the bank forecloses on the home.

Flanders, out of sympathy for the Simpsons, buys the home at the auction and rents it back to the Simpsons. The Simpsons are lousy tenants and Flanders evicts them. They spend a few nights in a homeless shelter. Yikes, this shit is getting real. Until…when Flanders tries to rent it out to new tenants, he is reminded of his affinity for the family (would we call this an instance of Stockholm Syndrome?), decides not to rent it out, and welcomes the Simpsons back home.

And that’s literally it. Weak sauce. When America is finally reaping the harsh, long-term consequences of its Simpsons-esque financial impropriety, the show depicts the Simpsons facing some short-term consequences that are solved by an implausible Flanders-ex-machina plot twist at the very end of the episode.

I’m assuming that the fact that their house is in foreclosure and Flanders is their landlord is not brought up in future episodes, so if that’s not the case, let me know and I might reconsider my argument.

Did anyone else see this episode and find it to be a major disappointment? Granted, I’m not sure how else they could have handled the issue of home foreclosure on the show, but the method they wound up using I found to be totally unsatisfactory.

I should add: Did anyone else see this episode and have a positive reaction to it? I’m open to explanations as to how the events of that episode can be interpreted to fit in the larger context of Simpsons plot devices.

Of course, you could just as well argue that the big drop off of the cliff came in the early-to-mid eighties, and that it is the result of Reaganomics and financial deregulation simultaneously driving massive government deficits alongside freely flowing clonsumer credit, with increasingly harsh bankruptcy laws.

Well you could. But where’s the fun in that?