Since 1908, Hollywood has been churning out adaptations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. Every portrayal detective in literature, film or television harkens back to 221B Baker St. (51° 31’25.50” N, 0° 09’30.89” W)* for those seemingly insignificant details, the flawed but determined investigator, and the big reveal at the end. Even medical shows are cheating off Doyle these days.

With examples ranging from the fabulous (Basil Rathbone, both on film and on the radio) to the awful (much of the Young Sherlock Holmes series), Holmes and his stories are well trodden territory, but there’s hope for tomorrow’s film will have something new. For the first time, we’ll get see Sherlock Holmes portrayed as a superhero by Robert Downey Jr., an actor who plays a good superhero.

Downey’s characters: arrogant, substance-abusing geniuses who put their minds to work to protect the innocent. Iron Man’s Tony Stark and Sherlock Holmes have an awful lot in common. Stark has an amazing, creative genius and access to the resources of a giant defense contractor. These advantages made him like a precocious toddler with first-strike capabilities, but they aren’t superhuman. Holmes, on the other hand, has a truly superhuman ability to absorb and retain knowledge.

Malcolm Gladwell. His superpower: inserting phrases like "the tipping point" into the popular lexicon against the will of the majority.

Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers introduced much of the reading public to the concept of the 10,000 hour rule. This included Hollywood. The rule states that it takes approximately 10,000 hours to master any single skill or discipline.

Want to play first violin with the New York Philharmonic? Set aside 10,000 hours for practice and you’ll get there.

Want to be the world tiddlywinks championship trophy? 10,000 hours and it’s yours for the taking.

Want to win Olympic Gold? You should have started working on that a couple of decades ago.

(10,000 hours takes about 10 years, Gladwell figures.)

In the first Holmes story, “A Study in Scarlet,” Dr. Watson produces the following list of the detective’s strengths and weaknesses:

I enumerated in my own mind all the various points upon which he had shown me that he was exceptionally well informed. I even took a pencil and jotted them down. I could not help smiling at the document when I had completed it. It ran in this way:

Sherlock Holmes — his limits

1. Knowledge of Literature. — Nil. 2. Philosophy. — Nil. 3. Astronomy. — Nil. 4. Politics. — Feeble. 5. Botany. — Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening. 6. Knowledge of Geology. — Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them. 7. Knowledge of Chemistry. — Profound. 8. Anatomy. — Accurate, but unsystematic 9. Sensational Literature. — Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century. 10. Plays the violin well. 11. Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman. 12. Has a good practical knowledge of British law.

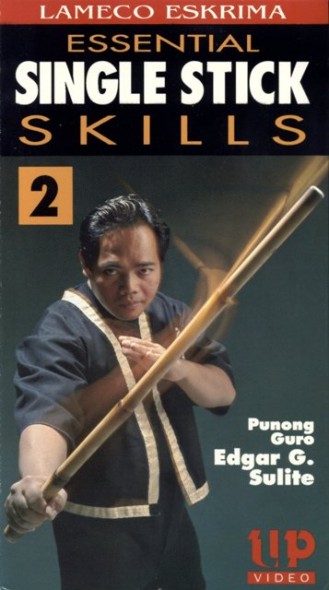

He was undefeated until he met the dark stranger with TWO sticks.

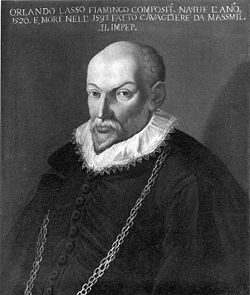

Subsequent stories expand on Holmes’s areas of expertise, demonstrating an expanding knowledge of politics (his brother, Mycroft works for the government and Holmes is brought in on several politically delicate cases), familiarity with European royalty, and an exhaustive knowledge of cigar ash. Holmes has written a monotype on this last subject, as well as on cryptography, on “the Polyphonic Motets of Lassus,” and, in his retirement, on the “Practical Handbook of Bee Culture, with Some Observations upon the Segregation of the Queen”

All of this in addition to his exhaustive knowledge of and consuming interest in crime.

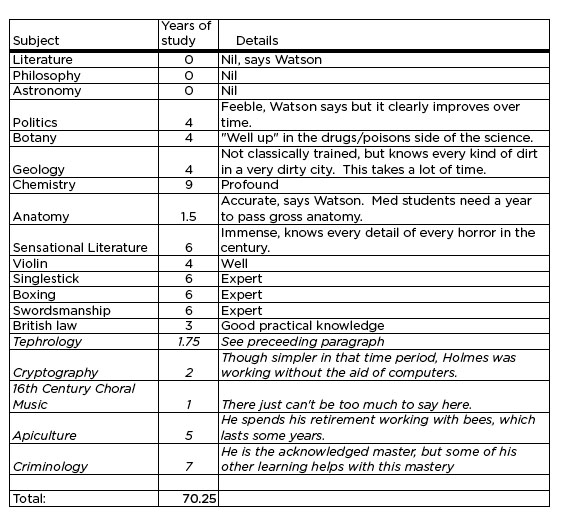

So, to Watson’s list we add the subjects of Holmes’s published materials, making Holmes an expert in tephrology, cryptography, 16th century choral music, apiculture, and criminology.

Obviously, Holmes is not a master of all the fields listed above, but we can extrapolate from Gladwell’s numbers, use other data and some common sense and arrive at a solid approximation of the amount of time it would take to achieve Holmes’s levels of proficiency in these fields.

BEGIN LONG CIGAR ASH DIGRESSION

Take the cigar ash, for instance. As Holmes says: “I found the ash of a cigar, which my special knowledge of tobacco ashes enables me to pronounce as an Indian cigar. I have, as you know, devoted some attention to this, and written a little monograph on the ashes of 140 different varieties of pipe, cigar, and cigarette tobacco. Having found the ash, I then looked round and discovered the stump among the moss where he had tossed it. It was an Indian cigar, of the variety which are rolled in Rotterdam.”

Sir Orlande de Lassus, Notorious Godfather of 16th Century Italian Choir Music

His monograph may have only considered 140 varieties of tobacco, but the 19th century was the highpoint of cigar smoking in England before the cigarette took over the market in the 20th century. In the 1830’s, England imported more than 250,000 lbs of tobacco. Millions of cigars came from all around the world, from hundreds of manufacturers and in thousands of different types.

Going back as far as the 1830s, the National Cigar Museum lists over 190 different brands of cigar that have names starting with the letter “A” and nearly 500 that start with “E.” Today, the self-proclaimed “world’s largest cigar store” carries more than 350 brands, each brand offering 5 or more types of cigar – 1750 individual cigars with different backgrounds and histories. Back then, smaller manufacturers weren’t competing against tobacco giants like Phillip Morris, so there were likely more brands then than exist today.

Let us grant, then, that in order to be able to correctly identify ash on sight, Holmes had to have examined the ashes of at least 1750 of types of cigars. He does not carry samples with him or send them back to the lab, which means close and careful analysis followed by memorization. Give Holmes half an hour to produce, examine, chemically analyze and commit to memory each type of ash. That’s 875 hours just on the cigars. Let’s be generous and say that he can complete both cigarettes and pipe tobacco in another 875 hours.

Holmes's discovery of a certain type of cigar ash led him to blame this man for the murder of Charles McCarthy in Boscombe Valley.

1750 hours is a lot, but it’s also a lot less than 10,000. According to Gladwell, Holmes is at best a journeyman tephrologist. If 1000 hours of practice takes a year to accomplish, it took Holmes 1.75 years to get this study done, what with his other jobs, classes and drug habits.

END LONG CIGAR ASH DIGRESSION

With that in mind, let’s look at how long it would take to learn Holmes’s other skills.

70 years. That’s how long it takes to learn the skills that Holmes obviously possesses at the end of his life. Excluding his retirement at the apiary, it drops to 65 years.

Holmes was supposedly born on January 6, 1854. Watson gives us the above description in 1881, when Holmes is is 27 years old. At 27, he possesses knowledge that would take an average person more than twice that time to learn.

Through some twist of genetics or Victorian mad-science, Holmes has the ability to absorb, retain and access knowledge and information at a rate no ordinary human could hope to equal. He uses that ability to punish evildoers and protect the innocent. Sherlock Holmes may have been the modern era’s first true superhero.

* Yes, Edgar Allen Poe wrote the first detective story, “Murders In the Rue Morgue.” That is a great story, and he deserves the credit for getting the ball rolling, but let’s be honest (spoiler alert): the murderer was an orangutan. If Poe were the true father of detective fiction, Clue would end with “It was the dog, in the library, with its teeth.” Poe may have sired the detective story, but ACD was the stepfather who taught it how to behave.

But Holmes’ knowledge of philosophy and literature was shown to be more expansive than Watson first estimated. In later stories, like The Sign of the Four, he quotes Geothe and Thomas Carlyle.

Caleb is right; it’s said that Watson believes Holmes related him this info as way to pull his leg. He regularly quotes Goethe, Shakespeare, and other obscure sources.

“The game is afoot!” is from Shakespeare (Henry IV and Henry V), and one of Holmes’ favorites.

Leaving aside the obvious (that Holmes learns “at the speed of plot”), the Holmes canon (and Gladwell?) assume an outdated conception of the psychology of knowledge. For normal people, making use of information requires active rehearsal of the retrieval and application processes. And for knowledge to remain accurate, there has to be some review and checking against the facts, otherwise memory can drift. So add to those 70 years time to read chemistry journals, practice his martial arts, and study flash cards for uncommon poisons. (That could also help with some of that knowledge quickly going out date, as would have been the case for least chemistry, anatomy, and cryptography during Holmes’s life.)

While the facts are indeed superhuman, you have to account for overlap in Holmes’ skill set. For example, singlestick and swordplay could clearly be related. Singlestick was born as a method of training French soldiers to fight with sabres. Additionally, his drug/poison botany skills may be attributed to his mastery of chemistry. This still leaves Holmes a mental superhuman, but a somewhat more understandable one. At least to me.

Ah, but can’t those hours of study be concurrent? Surely if I’ve spent 10,000 hours within the last ten years getting really good at typing, it doesn’t mean I can’t have also spent that same period of time attaining a proficiency in finding information on the web, playing piano, playing guitar, and operating Digital Audio Workstation Software. In fact, I’ve spent the last decade learning to do all these things and more, and I feel I’m quite proficient in all of them. (Plus, not all skill sets are created equal. Gladwell’s number is an average, but certainly it doesn’t take 10,000 hours to master Tic Tac Toe).

If you spend 10,000 hours divided evenly over a period of 10 years, then you’re only spending 2 hours and 45 minutes a day practicing your skill of choice. If you haven’t got a day job, then there’s lots of room in your day for getting good at multiple things at once.

Let’s crunch the numbers:

1 year has 8,760 hours.

10 years have 87,808 hours (including two leap years).

Of those 87,808 hours, let’s assume the average person will 30% of them asleep (that’s between 6 and 8 hours a night). That leaves 61,465.6 hours. Let’s get rid of the remainder, for convenience’s sake.

So now we’ve got 61,465 hours of discretionary time. Holmes went to school, obviously, and this is likely where he learned some of the rudimentary skills that he later used to fight crime.

Someone correct me if I’m wrong, but Holmes never had a day job outside of being the World’s First Consulting Detective, right? That leaves a ton of time for him to practice the varying skills that he knows will be useful to his pursuit of crimefighting.

These numbers, furthermore, assume that Holmes began his work at age 17, and made no progress of any sort beforehand.

In short, I don’t find Holmes’ accomplishments to be superhuman. Extraordinary, sure, but superhuman, no.

Idiocy, clearly. I wonder how many hours it took that guy to come up with that 10,000 hours load of it.