King of the World.

Recently, Fenzel spelled out Five Reasons Why Avatar Will Suck. I want to add one more. Every article that I’ve read about the movie waxes poetic about how Cameron has been given carte blanche to pursue his vision. He’s spent almost four years in production, and more than 300 million dollars. He even invented his own camera. This is a man with unlimited resources and total creative control. That makes me very nervous.

This may seem like a strange thing to say. Don’t we all agree that in a perfect world, all artists should have unfettered freedom? You don’t want gallery owners telling Picasso how to paint, or concert hall owners telling Mozart how to compose. And when it comes to artsy filmmakers, I completely agree. By all means, write Paul Thomas Anderson a blank check and leave him the hell alone.

But while Avatar is certainly art, it’s entertainment first and foremost. It’s a blockbuster, the most tricky of all genres to nail. Every year, there’s a handful of amazing dramas and hilarious comedies. But making a movie like Independence Day is subtle pop culture alchemy. How many awesome blockbusters has 2009 given us? I’d argue Star Trek, and that’s it. (And while Star Trek was fun, I don’t think it’s on the same level as The Dark Knight.)

Can't get his pet project funded. I'm not kidding.

To make a good blockbuster, you need a great director. Then you need to give him enough power to bring his vision to life. But there need to be checks and balances. A blockbuster is a populist creature – the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the director. The best blockbusters absolutely end up capturing the worldview of their creators… but that’s not their purpose. Good blockbusters are never self-indulgent; they are audience-indulgent.

To understand why Avatar worries me, you have to understand how rare Cameron’s level of absolute, godlike, no-questions-asked control is. For instance, many people assume that Steven Spielberg can go out and make any movie he wants. But back in February, The Big Money reported that he couldn’t find anyone to fund a Lincoln biopic he’s been cooking up.

Think about that: Steven Spielberg simply cannot get his movie off the ground. And it’s not a fluke thing.

The most recent issue of Esquire reports on Ryan Kavanaugh, a 34-year-old venture capitalist whose company is funding about 35 movies in 2010. The article begins with director Ron Howard waiting outside the guy’s office to ask for money. Just because Frost/Nixon was a success does not mean that people are rushing to finance Howard’s next project. Even for A-list directors, getting a movie greenlit can be tricky. Getting a massive blockbuster greenlit is even harder.

And even when they get the go-ahead, it doesn’t mean they call all the shots. They have limited budgets. They have producers calling in daily to discuss the rushes. They have demanding stars with massive egos.

James Cameron has been a pretty powerful guy for his whole career, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t had to deal with nervous and demanding studio executives. His battles with Fox during the Titanic shoot are legendary – at one point, he gave up his own salary to keep production going.

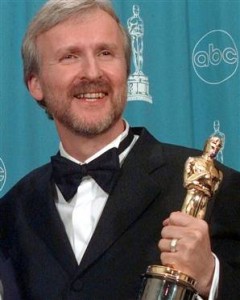

But as he himself memorably put it, Titanic’s success made him King of the World. I can only think of a few cases in recent history where a director had this kind of clout… and they didn’t end well.

After co-writing, directing, producing, and running the special effects company for the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Peter Jackson had a Cameron-level of mojo working in 2003. And like Cameron, he had a dream project that had been gestating for years. Jackson had actually shopped around a script for King Kong in 1996, which had the misfortune of landing on everyone’s desks right after Godzilla bombed at the box office. After the epic success of Rings, it didn’t surprise anyone that he signed a deal to make Kong (which made him the highest-paid director in Hollywood history).

I don’t want to suggest that King Kong is a terrible movie. I like it. If it were on right now, I’d say, “Ooh, King Kong. I like that movie.” But the movie is three hours and seven minutes. That’s almost twice the length of the original, which shares virtually the same plot. This isn’t an epic like Lord of the Rings that needs that kind of sprawl; it’s a simple, straightforward adventure movie. Three hours is too long, no matter how good each individual scene is.

We don’t even see Kong for seventy minutes. Those of you who know about the Ghost Ship Moment understand that this concerns me.

I think it’s a fair assumption that if it had been any other director besides Jackson, the studio would have insisted on a more bladder-friendly running time, and they would have been right. And the New York Times reported that in the end, Peter Jackson put up millions of his own money to cover the additional expense. You die-hard King Kong fans can argue with me, but I think all he did was buy enough expensive celluloid rope to hang himself with. The movie would have been better off shorter.

But even putting aside the running time, I’d argue that Peter Jackson could have done better with a little more studio pressure… because I’ve read the 1996 King Kong script. It’s available online here, and I think it’s better.

Quickly: how does the 2005 King Kong begin? Can you remember? Well, the 1996 script begins with a sensational dogfighting sequence set in World War I, introducing Jack Driscoll (the Adrian Brody character) as a young pilot. The scene does more than start the movie off with a bang – it establishes a couple important things about Driscoll’s character. And more importantly, it establishes he can fly a plane, because in the final reel, he steals an aircraft to try and protect Kong. In the 2005 Kong, Adrian Brody barely has anything to do in the last third of the movie. Having him jump in a plane seems much more satisfying. It also gives Ann Darrow a reason to take him back; he redeems himself for his part in Kong’s capture.

In a lot of different ways, the 1996 screenplay just works better. For instance, in the 2005 version, it is never made clear how the film producer (Jack Black) gets his hands on a map to Skull Island. He just shows up in his first scene waving it around. This is kind of a huge plot hole. And even if you buy this, why exactly is he looking for this uncharted island anyway? All he needs is a jungle to film an adventure screenplay he already has. The whole journey seems forced.

In the 1996 screenplay, the producer isn’t trying to make an adventure story – he’s a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not-style documentarian, hacking his way through jungles in search of beautiful bare-breasted natives he can film, always putting himself front and center. In this version, it makes perfect sense that he’s trying to find this mysterious island – that’s what he does. (Ann, by the way, isn’t an actress. She’s the daughter of a famous archeologist that Denham ripped off.)

The 1996 screenplay is faster, tighter, and more fun. No pointless monologues about Heart of Darkness. This was before Jackson had been nominated for an Oscar, and he wasn’t taking himself too seriously. More importantly, when Jackson sat down to write the 2003 screenplay, he knew it was getting made. He didn’t have to please anyone but himself. He’s a talented guy, and King Kong still has a lot going for it. Sadly, I can’t say as much for…

There are a million and one opinions about where the prequel trilogy went wrong. But let me point out that the original Star Wars was written over the course of many years, with the input of many different people. If you want, you can read a whole bunch of drafts online, which are wildly different than the actual movie. Star Wars didn’t spring fully formed from Lucas’s head – it was hammered out piece by piece.

Now think about Episode I. Lucas didn’t need anyone to greenlight it – he was financing it himself. And as any writer can tell you, after you finish that first draft, you invariably believe it’s a work of total genius. If you’re lucky, you wake up the next day and you’re able to see the flaws by yourself. For most people, you need some trusted readers to give you honest opinions. Did Lucas show Episode I to anyone who would be blunt with him? I’d guess his readers were either Lucasfilm employees, or close friends like Steven Spielberg who aren’t necessarily going to be harsh critics.

I think that even on his worst day, James Cameron is a better screenwriter and director than George Lucas. But I also think it’s a dangerous thing when you have the power to decide when your script is ready to shoot. You should have to spend months rewriting every word, even if no one’s forcing you to, because no screenplay is perfect right off the bat.

The only picture I could find of them together. Perfectly, it was the 2004 Visual Effects Society Awards.

I don’t know if Cameron is surrounded by yes-men who didn’t make him fix his script. But I do know that from a technical standpoint, there are an uncomfortable number of similarities between Avatar and Episode I. Both directors are obsessed with special effects, and famous for pushing the envelope with each project. Both are control freaks who dream about manipulating every detail of every frame. Both delayed their pet projects for years, waiting for more advanced technology to come along. Hell, even Cameron’s crusade to get 3D projectors into theaters parallels Lucas’s crusade to get digital projectors into theaters.

And the thing that worries me is, for all the hoopla, the special effects of the Star Wars prequels weren’t nearly good enough. Remember that scene from the end of Episode I, where the robots are fighting the Jar-Jars? Two computer-generated armies – a breathtaking technical achievement at the time. It also looks fake as hell. I honestly believe that Lucas, the Industrial Light and Magic CEO, bought his own hype, and believed that his effects were completely believable. He was probably tickled pink with the number of servers crunching teraflops of data they had going. In the end, he overreached – the technology wasn’t up to the challenge after all. The movie suffered the ultimate insult, losing the Visual Effects Oscar to The Matrix.

Cameron is also a tinkerer, completely in love with the toys he’s built for himself. When he shot Avatar, he could look through his camera and actually see the actors as their computer-generated selves, moving through the computer-generated set. It’s amazing technology, without a doubt. But nothing I’ve seen so far has blown me away. It looks great, but it still looks like special effects to me. (And I agree with Pete that the Na’vi designs aren’t too interesting.) Cameron could prove me wrong, but I wonder if as a special effects pioneer, he’s got a blind spot for the limits of the technology. (One of the many symptoms of Lucasitis.)

What is Frodo doing in my pool?

CASE STUDY: Lady In the Water

Obviously, M. Night Shyamalan isn’t in the same league as Lucas, Jackson, and Cameron. But he also makes much smaller movies, so he ends up having a similar level of clout. In July 2006, Entertainment Weekly published a behind-the-scenes look at Lady In the Water, and the combination of ego and the power to indulge that ego is staggering.

Shyamalan had the Lady In the Water script hand-delivered to four top Disney execs on a Sunday. He specifically chose a Sunday because he wanted their undivided attention (nevermind ruining their weekends). A couple days later, the four executives went out to dinner with Night, and expressed some reservations about the script. (What the article does not say is that the writer/director wrote a part for himself, as a writer whose work is so amazing that it brings about world peace. In other words, he cast himself as the messiah. That’s your first hint right there that Mr. Shyamalan is a… what’s the word… douche.)

Anyway, Night listens to their concerns graciously. Just kidding:

Night went into a long monologue of everything he had written as an adult, as a writer-for-hire, as a ghostwriter, as the writer of four original screenplays for Disney. He cited dollar figures, how the movies had ranked for their studios… Night had always thought they let him do his thing, as a writer and a director, because he had earned the right to do so. Now he was hearing something different. He was hearing: We didn’t put our foot down last time, and we regret it; we’re not going to make that mistake again.

“Last time” refers to The Village, a movie which got a 42% positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes. So yes, maybe these executives had a right to be a little concerned. At least, that’s what I think. He disagrees:

He had known these people for years. He had always liked them; he had always thought they were smart. He knew they were good people.

“Good” people. There’s an implication buried in there that disliking the script is somehow a moral failing. By the way, if you’re wondering how the author knows what Night is thinking, this is an excerpt from a book written by a guy who Night invited to follow him during Lady In the Water. Night must have told the guy about the dinner, probably believing it made him look like a sympathetic victim.

But here’s my favorite part of the story; the part that will make me hate M. Night Shyamalan forever.

Cook told Night he could still make the movie at Disney, even if the executives didn’t understand it. He said, ”Prove us wrong, Night. Just make the movie for us. We’ll give you $60 million and say, ‘Do what you want with it.’ We won’t touch it. We’ll see you at the premiere.”

”I can’t do that,” Night answered. Spend a year of his life trying to prove them wrong? No. What a waste of energy. Their lack of faith in Lady in the Water would infect the whole project.

”C’mon.”

”I want to thank you for six great years and four great movies,” Night said.

I honestly have trouble wrapping my brain around this. They offer him $60 million to make his movie, exactly the way he wants to make it. It’s every filmmaker’s dream. And M. Night Shyamalan turns the offer down, because he doesn’t want to work with someone who would even suggest (not insist, just suggest) that the script could use a little work.

You know how much I hate this guy? I cannot wait until he releases another movie, so I can watch it fail and imagine how devastated he is.

I am angry on behalf of the Terry Gilliams of this world. And I cannot tell you how much it pleases me that Lady In the Water was completely ripped apart by the critics and lost tens of millions of dollars for Warner Brothers.

Now the question is, do you believe that James Cameron is as full of himself as M. Night Shyamalan? If a Fox studio executive ever tried to give him some constructive feedback on Avatar, can you see him rattling off the domestic gross of Titanic and banning the guy from his set? I can. Cameron’s a great filmmaker. He’s also a raving egomaniac. And when raving egomaniacs become King of the World, they have a way of buying their own hype.

Hollywood executives have a bad reputation. It’s absolutely true that a lot of them are only interested in making a high-grossing product, and couldn’t care less about making a good movie. But while Hollywood executives are behind a lot of the movies that disappointed you the most, they are also behind most of your favorite movies. Ideally, their job is to make the movie better.

I know this seems controversial, but it’s true.

We geeks spend a lot of time railing against studio executives, wishing they would just give talented directors the freedom to make the movies they want. For the most part, we’re right. But there’s a point at which too much freedom becomes dangerous. Anyone who has been forced to rewrite something knows how agonizing a process it can be. If you’re Lucas, Jackson, Shamalan, or Cameron, and you don’t have to rewrite if you don’t want to… are you going to? Maybe you stop at five drafts instead of ten. After all, reporters are lined up to interview you for puff pieces about what a creative dynamo you are, and studios are in a bidding war to make absolutely anything you give them.

In Shyamalan’s case, he not only refused to listen to constructive criticism, he actually ostracized anyone who doubted his brilliance. What I want to know is, did Cameron have people in his inner circle who told him if the ending is corny, the jokes weren’t funny, or the whole thing needed to be ten minutes shorter? Bottom line: every emperor, no matter how powerful, needs someone to tell him if he has no clothes (or if Jar-Jar needs to be taken out back and shot). We’ll find out if Cameron had that soon enough.