Okay. Deep breath. I have three points that I want to make here, and I don’t really have time to integrate them, or expand on them as much as I’d like to. Next post I write about this, I’ll probably spend less time recapping the episodes and more getting into the analysis, because honestly, the people who have read this far will have already seen the series, and anyway the name of the site isn’t Overdescribingit.

First: Jouissance

So yeah, apparently I couldn’t make it one full post into this series before I alienate everyone by talking about Lacan. But this is Lacan-lite, I promise. Jouissance is a French word that’s a little difficult to translate: it means something like enjoyment, but with faintly racy overtones. Maybe ecstasy would be better, although jouissance doesn’t carry the same connotation of an extremely strong sensation. In Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory, jouissance is what we feel when our carefully constructed symbolic representation of the world slips for a second and instead we experience the world as it actually is. It’s not necessarily a pleasurable sensation – it can take the form of fear, nausea, boredom, or what-you-will – but jouissance works as a descriptor because there’s that hint of animalistic irrationality about it. (Now, there’s a LOT that’s wrong with this description, especially the phrase “the world as it actually is,” but there’s not much to be gained for our purposes by going into more detail.) For people who write about aesthetics from a Lacanian perspective, jouissance becomes a really critical concept, because you can make the argument that creating moments of jouissance is what Art, big-A Art, is really all about. This idea (or something very much like it) is actually quite a bit older than Lacan: don’t we all pretty much accept that art speaks to the emotions or to the spirit first, and the intellect second if at all?

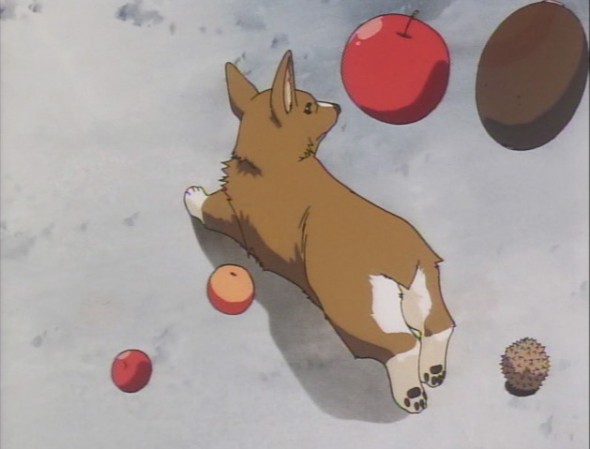

My take on Cowboy Bebop has to do with those strangely detached action sequences. The episodes are neatly divided: on one side, you have the plot, characters, motivation, and all the other rational elements of narrative fiction. On the other, you have these extended set pieces that are about nothing more (and nothing less!) than looking and sounding cool. And the sense of exhilaration and excitement that these scenes can create when they’re done well is pure audio-visual jouissance. You get this most obviously in the fight scenes, but not only there. The best example, for me, comes from Stray Dog Strut, where Abdul Hakim is chasing Ein through a market and stops to throw fruit at him.

This picture doesn’t really get the effect across at all. What makes the segment truly surreal is the way the fruit moves, because it’s not really in the same three dimensional space as the dog. None of it hits him – none of it even hits the pavement! Rather, it just moves from the top of the screen to the bottom of the screen. All of this is over in a second, so when you’re watching it you don’t have time to realize what’s weird about the motion. You just register it as weird, as motion that’s outside of the symbolic framework that governs our sense of how things are supposed to move. And this – call it jouissance, or anything else – is what makes the scene work, and arguably what makes the show work.

Second: Discipline.

And while we're on the S&M tip, let's not forget that they've found an excuse for Faye to get tied up like this in all three episodes she's been in so far.

In any work of art, there’s a power dynamic between the creators and the audience. The writers control what the audience sees, and when. Some are very kind: showing the audience what they want to see whenever they want to see it. Some make us work a little more. The creative team behind Cowboy Bebop are some sadistic controlling bastards. I don’t mean that they make the show unpleasant to watch. I just mean that the constant withholding of critical information and images is part of what makes the show what it is. Consider the stuff they keep back:

• We don’t get to see Katerina shooting Solensan (we just see the aftermath)

• We don’t get to know why Ein is so important

• We don’t get to see Spike and Faye’s poker game (instead, we get an oblique montage of casino-related imagery)

• We don’t get to see the Space Warriors turning into apes (we just cut away after the vial shatters)

• We don’t get to know what motivates Vicious’ power play within the crime syndicate

• And hey, while we’re on the subject of character motivations, we don’t get a reliable one of these for ANY of the main characters, at least not yet. One it’s own, this one is pretty normal for early in the run of a series. But as part of a pattern, it begins to look like something more than narrative convention. As part of this pattern, even the fact that the heroes never collect on a bounty starts to look like some kind of sick game.

The most interesting version, again, comes from Stray Dog Strut. At the end of one of the chases, Spike and Abdul Hakim confront eachother on a bridge. They’ve both been established as unspeakably badass martial artists. Surely we’re in for the kung-fu fight of the century, right? Remember, this is the second episode, and a big chunk of the first episode was devoted to kung fu, so at this point, it looks like Cowboy Bebop is basically a kung fu show. Especially since this episode has been dropping references to Bruce Lee and Game of Death at a rate of about one per minute. So what happens? Well, they fight for a second or two. But the camera stays focused on Ein the whole time. All we see is their feet shifting around, and occasionally zipping out of frame as one of them tries for a roundhouse kick. Okay, but surely that’s just the teaser, right? After all, that was in the first act. The final act will have the kung fu battle to end all kung fu battles, right? Wrong. Abdul Hakim crashes his car and gets arrested without confronting Spike again.

The writers used the second episode of the show to frustrate the expectations created by the first episode of the show. Hardcore.

Third: Formalism

Isn’t it interesting how different Ballad for Fallen Angels is from everything that came before it? This is maybe the most obvious point to make about the show, but no less worth making. It’s the first episode where we learn anything about Spike’s past. It’s also the first episode where he kills people. (In the earlier fight scenes, he would cheerfully jumpkick a guy with a machine gun, apparently just for the fun of it. In this one, he just shoots a whole bunch of people, and he’s quite businesslike about it.) It’s the first episode where Spike displays emotion about anything or anyone other than himself: whether he goes to rescue Faye because he doesn’t want her hurt or whether he just wants a chance to kill Vicious is an open question, but either way someone’s getting through to him. More trivially, it’s the first episode where the title card doesn’t have music (instead we get the sound of Vicious’ pet bird squawking), and I think the first where the little graphic that tells us we’re coming back from the commercial break doesn’t get any sound at all. It’s certainly the first episode where the awesome action scene has no music. The big musical set pieces here are reserved for the moments before and after the attack: Spike marching into the church and falling out of the window. During the fight itself, all we hear is gunfire.

So basically where the first four episodes are light, even frothy, the last one is as serious as a heart attack. In fact, it’s so serious that it almost wraps its way around to being silly again… or at least, serious enough that it violates narrative causality in that wonderful jouissance-provoking way. The “In the Rain” song in the video above is a great example of this, as is the scene in the opera box. When Faye turns and sees Mao Yenrai’s corpse, propped up in a chair with blood smeared down his face, eyes open as if he was watching the show, I don’t mind telling you that a chill ran down my spine. So as different as this episode is, it is still recognizably Cowboy Bebop. It still does trade on these little moments of surrealism. It still does have a bad-ass action sequence. It does still end with the honky tonk piano riff established in episode three.

In the comment thread for the last of these posts, Mlawski said that the story of Cowboy Bebop develops more like music than like a traditional narrative. Let’s lean on that metaphor a little. When you’re making an extended musical form, you only have two basic tools: repetition and variation. That is, each time you write a section of music, you have the option of 1) doing the same thing you just did again, and 2) doing something else. A third important technique (really just a version of the first two) is to do something, do something else for a little while, and then bring the first thing back. This is grotesquely oversimplified, but whatever. It does tend to play out in the way that actual musical forms work, whether it’s something relatively simple, like an ABAB song form, or something relatively complex, like Sonata form, which I would need a whole other post to even inadequately explain. The point though, is that it’s possible to make interesting and important shapes even if you never alter your basic building blocks at all, and even if the blocks don’t have “meaning” in the same way that stories typically have meaning.

Okay, so you see where I’m going with this, right? If Cowboy Bebop was a piece of music, the first four episodes would be variations on a single theme. The fifth episode would be a contrasting theme. We can probably expect a tug of war between these tendencies to play out over the duration of the show — possibly within individual episodes, but more likely (I’m guessing) between the different episodes. We’ll get a light one here, a dark one there, etc. and the pattern of light and dark that this creates will eventually determine the overall shape of the series. It will be interesting to see which one wins out in the end… and also whether there are any episodes that don’t fit into either category.

All right. Nothing more to see here, until you add it in the comments.

Hooray, more Bebop posts written by Stokes! A fine combination. Here are my random thoughts, in no particular order:

-I have to say, the first time I saw the show, I didn’t understand why Asteroid Blues was the first episode. The tone seemed different to me (yes, more nihilistic) than the usual episodes of the show, which are a mix of wackiness and cleverly staged fight scenes. This episode had the clever fight scene but not the wackiness.

Having seen the whole show, I can now say that Asteroid Blues IS the correct first episode. The parallels between it and the last episode are really interesting, for one thing. You say in your post that the first four wacky episodes of Bebop are the main theme, and the dark fifth episode is the counterpoint. I could also see it the other way around. The nihilism and darkness of the 1st and 5th episodes are the main theme, and the wackiness in between is the filler. Fun filler for sure (you still haven’t got up to the wacky drug comedy/blaxploitation episode or the wacky terrorist episode), but still filler, in a way.

-I think you brought up an interesting question about how much Bebop is a deconstruction of an anime/action show versus just a plain anime/action show. Or is it a sort of deconstructed reconstruction? I need to think about this more before I can answer.

-What I do think is different about Bebop in comparison to most other anime shows I’ve seen – and incredibly frustrating sometimes, especially later in the series – is, as you said, the amount the writers hold back. This is the only anime TV show I can think of (besides, of course, Evangelion) where there is more subtext than text-text. Compare Bebop to, say, Dragon Ball, and you will see what I mean. The characters in most anime shows, even the good ones like the aforementioned Evangelion, spend a lot of time talking about their feelings to one another, or at least to the audience. Bebop is unique -and, again, sometimes incredibly frustrating – because it is about four (or five, if you count the dog) main characters who almost never speak honestly to each other. I can think of one time in the show where Spike talks honestly to one of the other members of the main cast, and it was so shocking to me that I was chilled to the bone. Chilled, I say!

-I love all the commentary you have about the music. More, please!

A response to your episode 5 recap: Spike is being a dick within the context of the show for insulting Faye’s singing. However, it’s more of a 4th wall joke as Faye’s Japanese voice actress is Megumi Hayashibara, who is a popular Japanese songtress, voice actor and pop culture icon. The joke doesn’t really carry over into the English dub as Wendee Lee, while talented, isn’t on the same level as Ms. Hayashibara.

I view the reason the writers’ hold back information (both plot detail as well as denying viewer expectations) is that Cowboy Bebop is a juxtaposition of two common anime genres: the typical seinen and slice-of-life. We get the drama and violene that comes from the seinen genre’s target demographic (males 18-40). We also get the observation of Spike and Jet’s regular lives as the bounties they chase ultimately don’t tie into storyline of Spike’s past. Their lives are much more exciting as they’re space bounty hunters but it’s still an average day for them. Your example of the ending of Stray Dog Strut fits into place quite well in this aspect. We don’t always have the epic kung fu battle with our nemesis. Some times you just never confront them, some times they get arrested for pet trafficking. Life’s weird that way.

@Mlawski – Very interesting! I would not have put episodes 1 and 5 in the same category, but you’re right that 1 is way more dour than 2, 3, or 4. And I’m totally with you on the lighter episodes being the “filler” around the “real plot” that takes place in the serious episodes… the serious episodes are sort of definitionally where the “real” plot of a serial TV show takes place, even if the lighter ones are better overall (for which see Buffy the Vampire Slayer). I’m wondering, though, whether Cowboy Bebop is trying to turn this on its head somewhat, and argue that rather than focusing on some grand revenge narrative you should just kick back, eat some sauteed bell peppers, and play fetch with your super-intelligent Corgi. This is sort of the position that Bilbo Baggins takes at the beginning of the Hobbit, right? “Plot development? Drama? Oh, no, not for me. We don’t want any of that here, thank you. Wouldn’t you rather have some nice seed cake?”

@Riderlon – Cool to know! I never would have gotten that joke. So is Hayashibara basically a singer who gets voice acting work as a stunt, the way that Miley Cyrus might over here? Or is she just a voice actress who is also a successful singer? If it’s the latter, that’s astonishing… although I guess it shouldn’t surprise me that the status of voice actors is different in Japan than it is in the states, given that the status of animation as a whole is so different.

As to whether Cowboy Bebop can be seen as a slice of life drama… I’m a little hesitant to agree. It seems a little too packed with incident. Shouldn’t there be episodes where they just take the day off and do their laundry? (Not that any of them seem to own another set of clothes.) Or entire episodes where they’re just lounging around the ship en route to the next planet? But maybe I don’t quite understand what you mean by the term slice of life… is it really a well-defined anime genre? What would be the textbook example?

@stokes Ms. Hayashabira started off as a singer but eventually started doing roles as a voice actress for anime. She still does release new singles and albums every few years but she’s becoming more well known for her voice acting than her singing (especially in the West). She also still has a radio show if memory serves. She really has become something of a pop culture icon as opposed to just a singer/voice actress. According to her wikipedia page, she was also a licensed nurse at one point so she seems to be an all around success if you ask me.

Slice of life by definition is just a look into the daily life of our characters and examine what happens to them. It often includes some kind of observation on life or society and rarely has an overarcing plot. The pinnacle American example is the sitcom Seinfeld. Japanese anime and manga have two very distinct flavors of the genre: mundane and fantastical.

The mundane variety tends to be populated with comedies such as Azumanga Daioh (high school girls), Genshiken (college otaku), Crayon Shin-chan (5 year old boy’s antics) and Maison Ikkoku (boarding house tenets). Some have an overarching storyline while others are purely episodic. The fantastical variety tends to be populated with more drama such as Planetes (astronauts), Patlabor (mecha pilot), Kiki’s Delivery Service (witches) and The Melancholy of Suzumiya Haruhi (which is a comedy despite its title). I’ve heard arguments for Ranma 1/2 and Neon Genesis Evagelion as slice of life but I’m not willing to label them as such. Check out one of each type and you’ll have a good idea of what the genre consists of.

Cowboy Bebop gives us a fantastical flavor of the genre. We observe Jet and Spike’s life as bounty hunters in space. The series is fairly episodic as outside of the episodes dealing with the crew’s checkered pasts. We also get very notable observations on life and society. The first is that even with advanced technology, humanity is very much the same.We still have terrorists, organized crime and smugglers that exist today although their means are more science fiction. The second observation is that being a bounty hunter sucks. You’re always out of money between repairs, fines and feeding yourself. You’re in constant danger even with the most mundane tasks. I would not enjoy being a space cowboy one bit.

So… okay, I’m still confused. Isn’t any serial just a look into the daily lives of its characters? If you can have a slice-of-life show about mecha pilots, can you argume that Lost is a slice-of-life show about people stuck on a mysterious island? Is The Wire a slice-of-life show about the drug trade? Is Dexter a slice-of-life show about a serial killer who only kills other serial killers? Is the Illiad a slice-of-life poem about the Trojan War? They do all describe the events that — however interesting they seem from the outside — make up the protagonists’ daily lives, and all of them provide social commentary.

But you gave me a good long list of titles (for which thanks!), so probably I should just watch some of them and get back to you if I’m still confused.

@stokes Slice of Life is pretty hard to define and I explained it to the best of my ability (which really isn’t that great). One of the main characteristics (in my mind) is the lack of an overall important narrative. The Illaid and The Odyessey tell an overall stories of the Trojan War and Odysseus’ return home from the War. there’s a narrative there despite it just being a day in the life of Odysseus.

I’ll use Crayon Shin-chan as an example seeing as I’ve seen all of what’s been released in the US. Each episode is essentially standalone. No narrative is being told and we just see the hilarious antics of Shin. There are multipart episodes but they don’t affect the narrative setup which is Shin is 5, goes to school and drives his parents and teachers insane. The status quo is maintained at the end of the day.

Cowboy Bebop does this with its story. New characters are introduced but regardless of the success of this week’s chase, the status quo isn’t changed. Even when we do get a serious episode dealing with Jet, Spike or Faye’s past we get some character development with [my mouth staying shut to avoid spoilers].

The other issue is how non-slice of life anime do this for character development. They take a break from the action and shift tone to expand on someone’s backstory via a slice of life episode. Bleach is a big example of it from what I’ve been told.

I think Riderlon has a point in that there actually are a number of scenes where the characters are just waiting for something to happen. An argument could be made that the first scenes on the ship with the bell peppers and the kung fu are of this type. I seem to think there’s an episode later where Jet is fishing off the Bebop while waiting for laundry to dry. These daily activities are the true keys to understanding the characters: Jet grows Bonsai; Spike practices Jeet Kune Do.

At the same time, I disagree with Riderlon’s suggestion that Cowboy Bebop is largely a slice of life drama since it does have an overarching narrative. It is ‘going somewhere,’ but it takes its sweet time getting there. The closer you get to the end, the fewer side episodes you have until it’s all about the backstories and the choices these characters make about whether they will continue in the life they’ve led.

I say it’s a juxtaposition of seinen and slice of life genres. We have the standlone bounty episodes that don’t really tie into the oerall backstory. We also have sequences and entire episodes featuring realistic violence, adult situations and humor along with flat out depressing issues that people deal with like Post Traumatic Stress, addiction and betrayal that are common to seinen anime and manga like Berserk, Battle Royale and Noir.

@Riderlon: Yes, I understood that, but I disagree with the idea that it is a juxtaposition of the two groupings (I hesitate to say genres for reasons I’ll mention later). I agree wholeheartedly with the seinen elements (Black Lagoon being the closest in terms of content, style, and presentation), but I think that the slice of life elements, which I agree exist, only serve to further characterization rather than being juxtaposed with seinen.

Further, the fact that many of the bounty hunting episodes are among the darkest episodes suggests that they, while part of everyday life, are equally seinen in nature. In addition, some episodes that tie in to the main storyline do begin with apparently unrelated bounties. There isn’t always a clear line between episodes that delve into character stories and episodes that are just them doing their job.

I also disagree that The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya is from the slice of life genre. I believe it to be a very different animal all together.

Of course, I think it’s silly to say that something is ‘seinen’ as a genre since it’s a grouping that includes such diverse series as Elfen Lied, Detroit Metal City, Mushishi, and Mahoromatic. Four VERY different series that I would say fall in very different genres.

@Stokes: While it is true that everything works out for the worst here, not everything does. They win some and they lose some. I think that’s an important thing to consider. they will succeed with some bounties later.

This will be a bit of a long comment on the slice-of-life genre, since I don’t think Cowboy Bebop really fits. Of course, that’s my definition, and it is definitely one of the nebulous ones that will receive ten different answers from ten different people.

Personally, I’d say Cowboy Bebop is primarily an action series. Sure, there’s comedy and drama and character exploration and so on, but the main focus is on the action. It has some slice-of-life elements, but both drama and comedy can get bigger impact if the audience has some kind of connection with the characters, and slice-of-life is one method for creating that. But every single episode has some kind of major action that’s central to the story. Even Toys in the Attic, or the more comedic than most Mushroom Samba.

A lot of the series mentioned above I would classify as primarily sit-coms. This is a genre that most anime fans seem to have forgotten about. ^_^ They may focus on the every-day life of the characters, but it’s the “wacky and zany” life. Or, frequently in the Japanese case, the “cute and cuter” daily life. They have to keep up the constant stream of jokes, so we get the funny incidents. Granted, the characters seem to have a lot _more_ of them than most people, but the focus is on these moments, not on typical every-day life.

Incidentally, I think that’s one of the reason so many otaku got upset with the chocolate coronet scene in Lucky Star. That kind of tangential conversation does happen, but it isn’t the kind of constant set-up, punch-line, set-up, punch-line they were expecting.

If you want a good example of slice-of-life, check out Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou. Unfortunately, it isn’t officially available in English, and isn’t likely to be (unless Vertical’s upcoming release of Twin Spica does very well, in which case it’ll have a slim chance of being licensed).

It’s the “purest” slice-of-life story I know of. Sure, there are comedic and dramatic moments, and even actiony moments (the hurricane, for instance). But they’re not dominant or even primary elements.

For instance, one chapter involves the main character, Alpha, doing the following: She wakes up, putters around the house, makes coffee, and falls asleep waiting for customers. That’s it. There’s around three lines of dialogue in the entire chapter, all her speaking out loud to herself. No action, drama, or forced comedy. And it works. It takes a good storyteller, but they can do it.

This kind of thing is very different from the kind of thing shounen action manga like Bleach do. Those do sometimes break from the main story to follow/explore the characters, but it’s so they can power up (over 9000!) or show dramatic tragic pasts.

As far as Cowboy Bebop goes, they’re bounty hunters. Their daily life is full of exciting adventures. Even the quiet moments are usually tied in with this. Spike goes toe-to-toe with criminals frequently, so he practices Jeet Kun Do in his spare time. Not that it doesn’t, or can’t, have slice-of-life elements, they’re just very minor ones.

Action and Sci-Fi definitely come to mind when you mention the series. Slice-of-life, not so much.

I’ll add that slice-of-life seems to be a particularly Japanese thing. America just doesn’t have an equivalent. It isn’t a particularly common genre, but it does show up outside anime and manga. Yasujiru Ozu made some great slice-of-life movies. He’s got comedies and dramas as well, but for things available in English (Criterion carries several of his films) this is your best bet.

To finish, I’ll reiterate that this is a very undefined genre. Everyone is going to have slightly different views on it, and Riderlon’s view seems pretty common. This one is just mine, not any kind of “official” view.

But for me, of the series mentioned above, only Genshiken has any kind of significant slice-of-life element. Maison Ikkoku is more a romance/comedy. Azumanga Daioh is more sit-com, etc. It’s just very rare for this to be the, or even a, dominant element in a published-for-profit story. By nature, it’s hard to have any kind of gauge on how successful they’ll be before you actually try to sell them. Publishers will rarely want to take that risk. Even Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou has some elements (the data transfer, for instance) early on that are obviously meant to increase its saleability. Luckily it was popular enough that Ashinano has apparently been given enough freedom with his new series, Kabu no Isaki, to not have to pander.

IIRC Ms. Hayashibara (she used to have her own manga detailing her life) was a trainee nurse when she was “talent-spotted” to be a seiyuu. Later on she branched into music; very common among seiyuus in Japan.

Azumanga Daioh = “Seinfeld” with girls

I’m gonna nitpick a few of your points in the Discipline section…

“Consider the stuff they keep back:

• We don’t get to see Katerina shooting Solensan (we just see the aftermath)”

I think this is simply more dramatic, and not that a unique way to show a shooting.

“• We don’t get to know why Ein is so important”

I honestly think this was lazy writing, not a conscious choice of Reveal versus Conceal. Even if you’re suggesting the Reveal versus Conceal conceit as a byproduct rather than the creators’ conscious choice, what is the point? What does it add to the series and your enjoyment of it?

“ We don’t get to see Spike and Faye’s poker game (instead, we get an oblique montage of casino-related imagery)”

This I can see fitting your pattern.

“• We don’t get to see the Space Warriors turning into apes (we just cut away after the vial shatters)”

I feel like this was to save time and $$.

“• We don’t get to know what motivates Vicious’ power play within the crime syndicate”

And I hate this! I’m only on episode 10 so I hope this changes.

“• And hey, while we’re on the subject of character motivations, we don’t get a reliable one of these for ANY of the main characters, at least not yet.”

I’m hoping this is more of a symptom of early episodes than anything else.