Somewhere, there is a crime happening

In the first article in The American Tragic Hero series, I wrote:

In the first article in The American Tragic Hero series, I wrote:

“Above all else, America is dedicated to the proposition that ‘what happened to other countries isn’t going to happen to us.’ As such, our variations on the tragic hero struggle to buck free of their core restrictions, often with startling results.”

I still think this is true — American culture in general is not very good at contextualizing or coping with death or futility – “doom” has an adversarial place in the American mind, not something you cannot avoid as much as something you must outsmart or outlast. “Doom” is not a reason to cry — “Doom” is a crazy time-traveling scientist with a metal face and robot clones, or a thrilling gun battle carving its way through a demon-infested colony on Mars.

To connect with some of my previous writings, the American vampire is not like Dracula or Nosferatu, weighed down by futility, vendetta, or torturous hunger the American vampire is like Blade, drinking Capri Sun pouches from the blood bank while facing down infinite, inky darkness and stabbing it with a gas-powered stake gun while doing a flying jump kick — or Edward Cullen, bound, slowly but surely, by integrity, by discipline, by hope, and by faith in the fiction that he is still young and will always be young — to the comforting notion that love conquers all.

So, the American tragic hero takes many analogous forms. In #1, I identified John Rambo as a Reverse Tragic Hero, a hero who has his catharsis and suffering at the beginning of the story, and is driven by recognition of his tragic flaw to ascend to great heights.

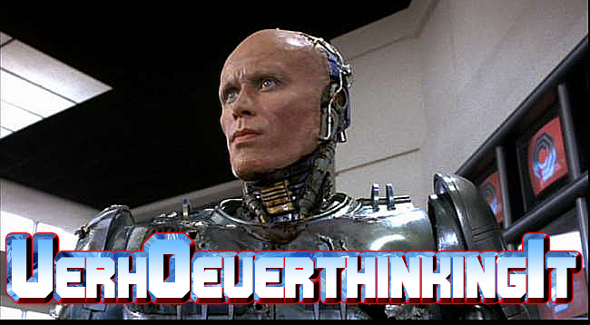

Here I will identify Robocop as the Indestructible Tragic Hero — a hero who treads the emotional and representative path of tragedy, who recognizes, who suffers, who loses something very precious to himself as he realizes what he has done to be punished so by fate — who leads the audience along a path of horror, pity and fear and prompts a purging of their collective moral selves with the intensity of the experience — and then who doesn’t have the good sense to die at the end or fade to a shade of his formal self. A tragic hero who goes through all these things that are his own fault, fairly or unfairly, but who still must pick himself up and go to work the next day, and who does not so much have to “come to terms” with his situation he persists by his very nature.

Picture this: Ajax the Great, upon rousing himself from madness and discovering he had killed a flock of sheep he thought were his friends and comrades, is crushed with guilt. In the Greek tragedy, he kills himself in shame. In the American story of the Indestructible Tragic Hero, we all share that horror with Ajax, we purge ourselves thanks to it, and then Ajax strolls down to the port to hop on the next trireme to a new tour of duty. He’s not happy about it. He feels pretty cruddy, in fact, and that cruddiness is never going to totally go away. But he has to do what he has to do.

Part of this is the convention of the Western, developed as it was in connection with various Italian and Japanese cultural mavens. Part is Hollywood’s eternal, bizarre demand for endings that can be seen as happy. Part of it is manifest destiny and a cultural work ethic — the belief that you can and you must keep going until you conquer the continent or pacify the world or any of that stuff — the march of America is unstoppable, and therefore, so must be the American.

In America, Sisyphus is admired for his hardcore lifting regimen, and Tantalus for his low body fat percentage.

Being a godless abomination spawned from human arrogance can be a downer sometimes, but in the end, it ain't so bad.

But part of it, I think, also comes from a young civilization that derives much of how it feels about humanity from its own experience rather than from ancestral stories, which carry with them a certain false, overdramatic perspective. In real life, this is generally how it goes down. Suicide is not nearly as common response to great moral failings or causal coincidences as it is in ancient tragedies. It’s pretty rare, in fact.

In reality, suicide is more commonly the result of a combination of bad luck, diseases, biochemical depressive states, opportunity, abuse, drugs, bad habits, and a host of other factors, few of which even approach the explanation “because it was necessary” or “because somebody deserved it.” In real life, you would rarely, rarely agree with the statement, “Yeah, I guess that person had no choice but to kill themselves.” (especially because of the poor pronoun/antecedent agreement) But this is a common expectation in old-style tragedies, as perhaps it was a more common belief in other civilizations.

In real life, seen through the lens of a single generation, people have to live with their mistakes. In real life, you don’t get the kindness of the story ending after you’ve realized you’ve done something terrible. As Chris Rock said, “People say life is short. Life ain’t short. Life is long.”

You may be struggling with whether you are a real person or whether the relationships in your life are meaningful or the work you do really improves the world around you or is instead in service to a giant evil corporation, but one thing remains true:

“Somewhere, there is a crime happening.”

And that means, if you are Robocop, you have your little tragedy, sure, but then you walk, like the half-robot you are; legs and arms whirring audibly, to your Ford Taurus, cue the theme music, cut to shot from the rig in front of the car, framing Robocop’s steel-solid face behind the windshield as the lights of Detroit flash by, and move on to Robocop 2*.

I leave you with this, which I found on the Internet, and which probably requires an introduction, but which I am not going to give, because I think it’s better when it comes up just short of making sense (with credit to The Zollie):

Oh, and just to be perfectly clear, Robocop is an awesome, wonderful movie. A masterwork. If you have never seen Robocop, you owe it to yourself to do so. As a bonus, except for the stop-motion ED-209, even the special effects hold up remarkably well.

* This, if you ask me, is the real tragedy.

“[Verhoeven is] like De Tocqueville with brief nudity and a higher body count.”

WIN.

Also, video punchline at the end = WIN

Great article.

It isn’t pop culture, but another great depiction of the American tragic hero can be found in Arthur Miller’s play A View From The Bridge.

Just read Perich, Stokes, Belinkie, Lee and now this…I’m loving Verhoeverthinking It with a level of intensity it definitely deserves.

PS – OT @Fenzel: can you do a post on the syntactic genius of the Wu-Tang Clan such that they can make this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothin ta fuck with.

actually mean this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan is nothing to fuck with.

The laws of grammar and double-negatives dictate that the first sentence should mean that the Wu-Tang Clan is not nothing to fuck with, i.e. that the Clan is indeed something to fuck with.

However, any listener immediately takes the second sentence as the true meaning.

How is this possible?