The American Dream: “I’d buy that for a dollar!”

I always thought Officer Lewis was one of the most interesting female characters in an 80s action movie. Sadly, I will remain part of the problem and not really write about her much here. But stay tuned!

Much like Stokes wrote about Verhoeven’s work being a study in “good movies” vs. “bad movies,” Robocop is a study in duality — public/private, city/suburbs, partner/friend, civilized/savage, man/machine, drug dealer/corporate raider, progress/decline, stop-motion animation/guy wearing a suit.

The movie hybridizes most of these distinctions — shows us one folding inside the other. What is it like when a government institution is a private corporation and a private corporation is a government institution? What is it like when apparent technological and social progress are the same as systemic failure and grand barbarism? What happens when a man hooked into a sophisticated computer system with perfect recall who can access mainframes in his mind with a flick of the wrist can’t remember his own name? Verhoeven even puts the men and the women in the same locker room — a trick he uses to challenge and excite the audience in Starship Troopers as well.

Years ago, I identified Robocop, minus the specific robotic cops (which seemed impractically designed), as the portrayal of the future from 80s science fiction most likely to turn out to be accurate. With the decay of Detroit, the continued meshing of private and public, the widening gap between rich and poor, the heightening divide between the clean, corporate, orderly America and the dirty world of the declining American city, the ever-building corporate control of American government in general and city planning in particular, the rise of mediocre, oversexualized schlub/hotty entertainments, and even the development of automated military and law enforcement capabilities, it seems pretty close to the mark.

Part of why it is so insightful is because it breaks down these dichotomies, which, to an extent, are illusions that we force on reality in order to make sense of it. We misidentify the march of history when we insist it makes more sense or stays more within the lines than it actually does — when we carve out dualities and presume they will be at some point distinct. In truth, not only do such bifurcations almost always collapse, but the clean lines are rarely there in the first place.

Well, America is also a study in collapsed duality: from its very birth and beforehand, two callings — two promises have vied for the soul and intentions of American culture, as they have persisted in the souls of many nations older and younger:

The call to homeland — The promise of a new continent where regular people can live, raise their families, and practice their ways of life freely, justly, humbly, and with dignity.

The call to prosperity — The promise of vast resources and free enterprise to build wealth, solve problems, alleviate suffering, better the world, bring pleasure and happiness, and defeat our enemies.

The duality that folds within itself? Move to America for a simple, humble life away from the mischief of the rest of the world, and also have opportunity to make massive amounts of money by getting all up in everybody else’s business. The two promises live in symbiosis with one another.

The call to homeland brings us citizen soldiers, the Bill of Rights, Quaker Oats, the white picket fence and the Square Deal. The call to prosperity brings us the arsenal of democracy, the sea-to-shining-sea, the boostrapping millionaire, summer blockbusters and Silicon Valley.

Over the centuries, this divide has promoted many other dichotomies — the “homeland” antifederalists vs. the “prosperity” federalists, the “homeland” articles of confederation vs. the “prosperity” Constitution, the “homeland” agrarian South vs. the “prosperity” industrial North, the “homeland” free silver movement vs. the “prosperity” gold standard status quo — all the way to the “homeland” anti-deficit hawks vs. the “prosperity” economic interventionalists, or, cutting the other way, the “homeland” healthcare reform movement vs. the “prosperity” resistance from insurance companies and their allies.

The deep and ironic divide tends to cut both ways whenever it exists. The Union sees itself as protecting the basic rights of southern slaves and the integrity of the country while attacking the plantation fat cats who seek to dominate them and tear it apart, while the Confederacy sees itself as protecting the basic rights of southern farmers and independent states while attacking factory fat cats who seek to dominate them and bring the whole country under unconstitutional oligarchy. Republicans seek to break the greedy stranglehold of government on regular Americans, while Democrats seek to break the greedy stranglehold of business interests on regular Americans, and business and government practically have a joint checking account.

Or to step away from politics, take the pot-and-kettling of independent and mainstream film. Corporations compromise the dignity, independence and character of everyday Americans by manufacturing and cheapening the culture, while indie filmmakers compromise the dignity, independence and character of everyday Americans by spreading self-aggrandizing product that slanders regular people for their taste and has nothing but contempt for a vibrant zeitgeist upon which it subsists but never thrives — ever the self-loathing parasite.

The way conflicts like these tend to be articulated show us more of what we have in common than what splits us. At the core of most arguments that cut along this warp and woof: the belief that, if you are good, you will rise to greatness, but that if you seize greatness, you will cease being good.

Leave home to get an education and more income, and you lose your small-town values. Work hard all your life to follow your dreams, and the money you make will assure you never find them. Set out for Washington to get elected and solve the problems the country faces, and the system will ensnare you with privilege and graft until others depart your home to pursue you and bring you down (and become you). Be fooled by the rocks that you’ve got, and you will forget you were Jenny from the Block, losing all the honor and respect that the title confers (and despite the fact that, were it not for the rocks, nobody would know who Jenny from the Block is in the first place).

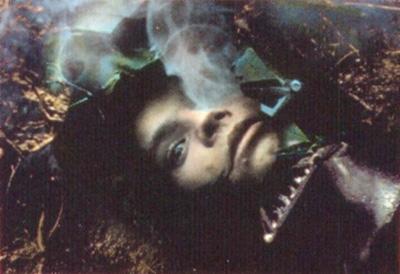

The saddest most difficult situations are those where a threatened homeland can be saved from external corruption by self-corruption — cut off Darth Vader’s head, and you will see your own face behind his mask.

Most literary traditions have this dichotomy somewhere in their culture, and the way their great works of literature address it tends to inform the national character (to the extent that one exists and is not a trick of the light).

And for those who would say Paul Verhoeven is not American, I would say most of the most compelling critics of the American mind and American experiment have come from overseas, and Verhoeven is among them. He’s like De Tocqueville with brief nudity and a higher body count.

“[Verhoeven is] like De Tocqueville with brief nudity and a higher body count.”

WIN.

Also, video punchline at the end = WIN

Great article.

It isn’t pop culture, but another great depiction of the American tragic hero can be found in Arthur Miller’s play A View From The Bridge.

Just read Perich, Stokes, Belinkie, Lee and now this…I’m loving Verhoeverthinking It with a level of intensity it definitely deserves.

PS – OT @Fenzel: can you do a post on the syntactic genius of the Wu-Tang Clan such that they can make this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothin ta fuck with.

actually mean this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan is nothing to fuck with.

The laws of grammar and double-negatives dictate that the first sentence should mean that the Wu-Tang Clan is not nothing to fuck with, i.e. that the Clan is indeed something to fuck with.

However, any listener immediately takes the second sentence as the true meaning.

How is this possible?