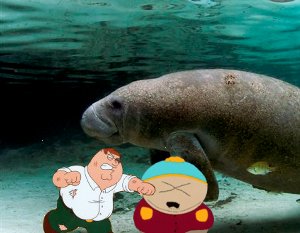

South Park and Family Guy don’t get along. In 2006, the two-part South Park episode “Cartoon Wars” characterized the writers of Family Guy as an a tank full of manatees randomly manipulating beach balls to generate the show’s scripts. Cartman (who is often depicted as a comedy writer) voices his (and according to the commentary track, the show’s) complaint thus:

“I am nothing like Family Guy! When I make jokes they are inherent to a story! Deep situational and emotional jokes based on what is relevant and has a point, not just one random interchangable joke after another!” —Eric Cartman, “Cartoon Wars I,” South Park

Family Guy made no immediate response, but this season produced the episode “Spies Reminiscent of Us,” which featured a dig at South Park‘s argument.

Peter gets the only laughs (big, loud, suspiciously artificial laughs) of the improv show when he injects out-of-context, pre-written gags. Even though the audience loves Peter, Quagmire sees the show as a failure. During their group’s rehearsal, Quagmire repeats many of the mantras of traditional improv comedy, including “don’t think” and “keep it going.” Quagmire seems to be a stand-in for a particular philosophy toward comedy outlined by Del Close and Charna Halpern in their improvisational comedy work. The philosophy promotes exactly the kind of organic, narrative, character-based comedy described by Cartman in the top quote. In Family Guy, Quagmire’s adherence to this philosophy at the expense of entertainment put him at odds with Peter (and, therefore, Seth MacFarlane) and, because Peter got laughs and Quagmire did not, in the wrong.

If the conflict between the two shows is a conflict between two comic ideologies, we at least understand the theatre-geek mentality that produces South Park. What, then, is the theory inside Family Guy, and why does it clash with what Cartman describes as “emotional” comedy?

South Park‘s major problem with Family Guy is the insert gag. In “Cartoon Wars,” the fictional episode of Family Guy seems to be a string of (uncharitably flat) cutaway jokes that do not relate to the narrative action. For South Park, these gags are not funny because they are “random,” not because the joke isn’t funny. The “randomness” interrupts the diegetic reality of the central emotional narrative of the episode by diverting the plot (momentarily) into a parallel universe without a causal or physical relationship with the narrative universe. Since the jokes can never change the circumstances of the central narrative, they are without emotional weight. The audience is not permitted to relate to these gags as anything other than cleverness. It is the narrative equivalent of a stand-up monologue, rather than improv theatre.

Aristotle’s Poetics lists the tools used to create emotional connections with the action of a narrative: unity of time, unity of action and unity of place. By firmly establishing a boundary around the story (it occurs over this time period, contains these events and happens here), the narrative gives a window into a universe in which the audience’s reality does not exist. In this way, the audience can temporarily abandon their identities in favor of the unity of the story. This allows for an emotional purging (catharsis) at the end of the action. When these unities are disrupted by anything that undermines the “rules” of the story’s universe, the catharsis is diluted.

Family Guy employs certain tricks from Aristotle’s bag, including the three-act structure, a plot that arises from character flaws, etc. Where Family Guy diverges is in its relationship to hammerspace. Hammerspace, in cartoon comedy, is the unrepresentable, infinite space that a character might reach into to retrieve a hammer (or anything else). Family Guy uses time the way Bugs Bunny or Harpo Marx use hammerspace, reaching into the hammer-timespace continuum to pull out a gag. The gag that occurs in hammertime is as separate from the temporal causality of the show’s narrative universe as the hypothetical hammer is from Bugs Bunny’s spatial universe, which is to say, both separate and not separate. Gilles Deleuze describes this world without boundaries, without dialectics, as a “plane of immanence.” All of the unities that Aristotle declared essential to creating a subject-object relationship between the audience and the events of the story are suddenly mutable and non-unified.

“Immanence is not related to Some Thing as a unity superior to all things or to a Subject as an act that brings about a synthesis of things: it is only when immanence is no longer immanece to anything other than itself that we can speak of a plane of immanence.” —Gilles Deleuze, Pure Immanence

Stewie's having a hard time coming up with a Gilles Deleuze joke.

When Peter or another Family Guy character says, “This is worse than the time…” and brings us into hammertime and hammerspace for a gag, we are not traveling into the plane of immanence. Rather, the plane of immanence is all of Family Guy, and all of the comedy universe that is connected to the hammer-timespace continuum. Our consciousness cannot experience the universe causally, as there is no causality (though there is also enough causality for plot). Our senses are useless, because the universe has no concrete set of rules that generates the sensations we would use to experience it (though we can see and hear the universe as it is presented to us). At any moment, any rule at all may be broken, including the rules that tell us who we are specifically supposed to be. As Deleuze puts it, “the life” becomes “a life,” loose in a boundless existence.

The post-structuralism of Family Guy is offensive to the structuralist, modernist, constantly-proselytizing children of South Park. While Family Guy is perfectly capable of including South Park in its world view, South Park, a show that comes from a specific theatrical tradition tied strongly to Aristotle, rejects the anti-dialectic of the immanent world. This one-sided argument is why Family Guy couldn’t retaliate with their own criticism of South Park, apart from a broad swipe at Quagmire’s theatrical demagogy. Family Guy can’t really have a point of view, since it undermines subjecthood, so it can’t really attack another point of view. The best it can do is defend itself by arguing that, if it’s funny, it’s probably all right. Seth MacFarlane said as much at Harvard University in June, 2006:

“…cutaways and flashbacks have nothing to do with the story. They’re just there to be ‘funny’. That is a shallow indulgence that South Park is quite above, and, for that, I salute them.” —Seth MacFarlane