Narrativizing

So, having hopefully wedged apart the literary clamshell of catharsis and brushed off that we are paradoxically healing alongside characters who are suffering, let us consider what it is to narrativize a loss.

Narrativization is one of the most important concepts in overthinking – the urgent human need to make chaotic and multideterministic existence or stimuli comfortable or comprehendible by forging it into a story is one of the basic hungers that drives the constant production of pop culture – and certainly informs its ephemeral quality. New songs, new shows, new movies are like the fabric of the fates, constantly being spun out to keep up with the progression of the living world.

And not just grief for deaths or big tragedies, but really all losses drive an impetus for narrativization – take the pain you have encountered and make it into a story. Link did not hit box overlay with zone 345×1414 prompting a sprite redraw, further hit box interaction and a status change – he touched a statue that became a soldier and it hit him.

I hope I have somewhat desanctified this impulse – made a case that it is neither normative nor explicative – that making a loss into a story for its own sake does not necessarily fix it, or make you feel better, or find the core truth of it.

What remains is an open-ended impulse that emerges from the basic concepts of emotional learning – something critical for children that becomes more optional, but still important, as we grow up, remapping and re-explaining the world to ourselves to cope with the shifts our amygdalas force on our perceptions as powerful emotional experiences affect the way we perceive and react to what is around us.

Consider Where the Wild Things Are again. One of the unifying motifs of the movie is the destruction of the igloo. Max’s loss of his igloo is a very painful loss that prompts an immediate and drastic emotional reaction out of line with what a rational narrativization might recall, but in line with what tends to actually happen. This new emotion is so terrible, so difficult, that Max explores ways to narrativize it – and also to engage in dramatic play – act out this idea, explore it from different directions, until he can assimilate it.

This doesn’t make his pain go away, necessarily. It doesn’t stop him from acting out in the presence of his mom. But it does help him understand that he loves her, even when he is mad, and that she loves him, even when he is alone or being denied what he wants. What he does with that, then, is anybody’s guess.

Consider The Wrestler again – all the times in the movie the Ram Jam comes up as a motif. The celebratory letters on the Nintendo game that Randy briefly and joyfully plays with the neighborhood kid in the trailer park. The chant of the crowd and its promise of adoration in exchange for it. The Ram Jam is Randy’s death sentence, but it is connected with the few things in his life that encourage him and give him what he thinks is love.

This is also a narrativization, but it is not therapeutic at all. It is a learning experience that teaches Randy little of use – it only teaches him self-destruction. Throughout his history, Randy had plenty of opportunities to give up wrestling and be with his family, which would have no doubt led to him ending up happier and more successful (except for his fleeing moments of joy, his life does get to a point where it is pretty miserable).

And yet I insisted to the friend I saw the movie with that The Wrestler isn’t a cautionary tale. It isn’t about what is right or wrong about with Randy’s choice to be a professional wrestler.

Because what is healthy for you, what makes you happy, and what is true are sometimes not the same thing – and seldom so at the same time.

I think this emotional insight is at the heart of Where the Wild Things Are, in the character of the child exploring new and scary emotions, in The Wrestler, which tells the story of a man whose emotional life is warped around his drive to make what many would consider a peculiar sort of art, and, in a briefer, more introductory way, is a starting place from which Up proceeds when it ceases to be sad and starts being a mundane kids movie (in which those three things are almost always the same – ah, mundane kids entertainment, where brushing one’s teeth, recycling or walking a dog are at once great for you, great for the world, and thoroughly fulfilling).

What, then unifies all these specific moments of sadness?

I’ve I think it’s the act of narrativization itself – because each scene is structured to present you with the stimulus and demand that you to narrativize it. It is definitely notable about all three scenes that inspired tears that:

- None of them include meaningful dialogue

- They are all presented as montages of disconnected shots with at least a few jump cuts

- They all have include patterns or shapes with established meanings (Randy’s glance at what might be his daughter’s outfit, the heart with the C in it from Carol’s ruined diorama, the measured pace and comfortable iconography of the “happy couple” Pixar sequence)

- They are all packed with stimuli – sound, visuals, movement – they all move quickly, and they all challenge the mind

Each moment includes some difficult, paradoxical ideas – the death of a baby in a children’s movie, the victorious special move that leads to death, the happy monster friend you are abandoning to never see again – and is presented in a way to force the audience’s mind to put the pieces together. And each is permeated by a powerful sense of loss.

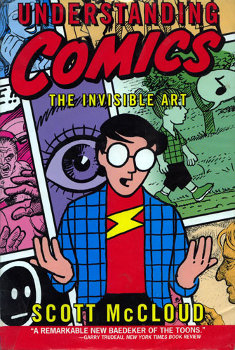

It’s much like the phenomenon of closure as described in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics – in one panel, you show an axe blade falling. In the next, the deed is done, or it is shown from outside. In the urge to form a story out of it, the mind fills in the blanks, and does so more horribly than the author ever could.

Psychologically, this would point to the modular act of the narrativization of a loss as in itself an act of grieving, even if it is not a loss of your own, even if it serves no normative purpose related to health or the negotiation of the events and state of one’s own life. Even if it just for a movie.

It’s hearing the gunshot that killed Old Yeller, but not being permitted to see it easily yourself – having to fill in the details from limited information.

The value behind the crying is artistic, not psychological, but it is produced from an understanding of the psychological that emerges from craft and technique – like most synthesis of disparate elements drawn together in powerful moments, pieces with limited intrinsic meaning become far more meaningful in juxtaposition or collage.

I am reminded of the last time, prior to 2009, when I cried this profusely in a movie – it was a similar scene in Big Fish, the (where’s the Pokemon again?) presentational rush to the river where the son carries his father toward death surrounded by the gathering characters of all his father’s stories. The movie does not do the work of narrativizing the loss for you. It gives you enough to figure out a loss is being suffered, and it depends on the lack of cogency or essential unity in the psychological experience of grief for you to put the pieces of it together.

It asks you to cope ugly.

And cope ugly I did.

Though I take some consolation in the fact that Rowdy Roddy Piper did too.

Though I don’t know if he cried during Wild Things.

And no, not the Neve Campbell, Denise Richards, Kevin Bacon movie.

Sheesh.

Oh, and the secret to happiness? Be resilient. Make the most of the good times. And try not to let things fall apart when things go badly.

Great stuff. The closing had me coping ugly just a teensy bit

The ending to the Wrestler is less ambiguous than you make it out to be. There can’t be any doubt that Randy died. When he comes off the turnbuckle for the Ram Jam the camera switches to a 1st person POV. The closing shot is of the lights. Meaning Randy is on his back.

The symbolism is heavy, only a wrestler who has lost his match stares up the lights as he’s being pinned. Randy as the babyface in a reunion match against an opponent doing the evil foreigner gimmick would never do the job, the crowd would be sent home happy that the all-American wrestler has conquered the invading foreign menace. This is even more the case after Randy hits his patented finisher. Even if this was one match in a series of matches the heel would never shake off the face’s finisher to win the match. So Randy is laying on his back after a heart attack.

The symbolism is much more than just Randy’s death. Its that life has pinned him, and the match is over.