People complained that I made page breaks too frequently, so here you go

At that point, anything that even suggests an emotionally charged memory can set off alarm bells – you see a seat belt and you freak out. You walk into a crowded room and you start hyperventilating. You vomit uncontrollably whenever you hear the word “Pilgrim” (Wing Commander movie reference. Apologies.).

So, on one hand, emotional memories help us learn and remember the world. They are essential to our survival, and especially important to children, who have to learn all the many bounties in God’s creation that are not for eating – like dust kittens or 9 volt batteries.

But on the other, emotional memories can eff us up and make us sick. They can stick in our craw and hurt us – prevent us from doing things we like or need to do, damage our ability to do things that we or somebody else have deemed are important for reasons unrelated to our own emotional states (such as, say, care for children or hold down a job).

Carl from Up is clearly damaged by his painful memories of Ellie. He talks to her picture. He rarely leaves his house. His personality changes; he becomes antisocial and violent. As romantic as this is, it is probably not the way for Carl to live his life (which is what Up is about).

Emotion helps create the world around us, but it can also put it in a stranglehold. We can be empowered by emotionally-turbocharged learning and experience in the world, but we can also be so damaged by the things we find that we require professional help to move on with our lives.

This space around these two purposes, these two powers emotion has, is where a lot of art and philosophy lives. Sometimes they intersect – as in childhood traumas related to learning disabilities – but usually they float on either side of experience; emotion the instructor and emotion the punisher. Lessons Learned and Love’s Labours Lost. In negotiating this difficult place (which all three of our featured 2009 movies do, in very similar ways, ‘natch), I’d encourage you to remember two fundamental things:

1. The dual goals of learning and being healthy neither totally explain emotions nor give a strong imperative about what an average person ought to do with them.

2.Whatever a therapist does for you, it is not strictly the same as art, philosophy or truth.

A corollary to that – it is not the goal of art to make you feel better.

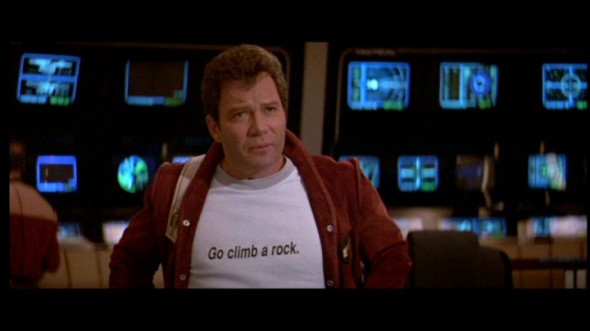

Psychological controversy and Star Trek V

Since today is all about narrativizing things (and reducing them by narrativization from incomprehensible complexity to something we understand, hint hint), allow me to narrativize the history of psychology for you.

Psychology as an intellectual discipline emerged from art and literature’s attempts to understand the mind, motivate and character. It is often said that Shakespeare was one of the early muses of the science. The great early psychologists, not coincidentally, were also great writers. The psychological systems of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung work like fiction – phenomena have causes, real or mysterious, and the peering eye or listening ear seeks for what it can find to unravel the truth of what is going on.

True causes are cloaked in guile and deception, surprise transformations and transmutation of psychological cause and effects are commonplace. Once the truth is unraveled, the psychologist declares a certain success over the problem. People are like books – the first step to fulfilling their purpose is to read them. Relative to the climax of diagnosis, treatment is denouement. The rest is trivial by comparison.

Think of Randy from The Wrestler atop the turnbuckle, about to leap to his doom. In that moment, Randy has a revelation, and at once understands his life and everything that leads up to this point. This is a psychological breakthrough!

At some point along the line, the scientific method began to creep more thoroughly into this poetry. Psychology became increasingly focused on not just causes, but results. “It is all well and good, Mr. Freud, that you have determined my wife wishes she had a penis, but hooking her on cocaine seems to have been, dare I say, a net negative.”

Think of Randy from The Wrestler after his epiphany. He leaps from the turnbuckle and is probably dead. How can we say this revelation was a uniformly good thing?

From an artistic standpoint, we can admire it. From the standpoint of the pursuit of the truth of the human condition, we can pity it and fear it. But from a psychological standpoint, mentally unbalanced people killing themselves is straight-up bad news.

As psychology got its legs under itself as a professional practice and medicine also improved and evolved, it became more important to demonstrate that what you were doing actually helped somebody. This is where we find the most elusive and difficult to grasp fact about psychology:

Psychology rarely determines whether something is good or bad, true or untrue, desirable or undesirable. Psychology is primarily tasked with determining what is healthy. You can have the craziest whacked out motivations or memories or complex oedipal fantasies in the world, but if it doesn’t impact you in a way that can be defined as health, psychology offers you little help in determining what you ought to do about it.

And it is an entirely possible outcome that the truth is not healthy for you.

The narrative seems neat, except that this process is not a one-way arrow – both the old way of looking at therapy as discovery and the new way of looking at empirical evidence of improvement are still practiced. One of the major practical controversies in contemporary psychological treatment, even if it is not the most popular to talk about – to what extent is talking about the problem solving the problem, and to what extent is it not?

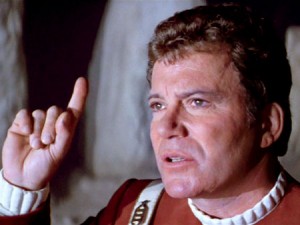

When Captain Kirk yells that he “needs his pain!” is he right?

Great stuff. The closing had me coping ugly just a teensy bit

The ending to the Wrestler is less ambiguous than you make it out to be. There can’t be any doubt that Randy died. When he comes off the turnbuckle for the Ram Jam the camera switches to a 1st person POV. The closing shot is of the lights. Meaning Randy is on his back.

The symbolism is heavy, only a wrestler who has lost his match stares up the lights as he’s being pinned. Randy as the babyface in a reunion match against an opponent doing the evil foreigner gimmick would never do the job, the crowd would be sent home happy that the all-American wrestler has conquered the invading foreign menace. This is even more the case after Randy hits his patented finisher. Even if this was one match in a series of matches the heel would never shake off the face’s finisher to win the match. So Randy is laying on his back after a heart attack.

The symbolism is much more than just Randy’s death. Its that life has pinned him, and the match is over.