In 2008 and 2009, the zombies have taken over. From the multiplex to the classics of 10th grade literature, the shambling undead hordes have gnawed their way into America’s hearts and skulls since they first appeared in 1968.

But the real origins of today’s zombies don’t lie with George Romero or Dan O’Bannon. Nor do they come from the Voo-Doo mind-control zombie films of the 1940’s. No, the first zombies to invade our popular culture died 3700 years ago, appeared in popular American literature in 1868 and appeared on screen in 1932. They were called Mummies and it seems that they’ve been forgotten this Halloween.

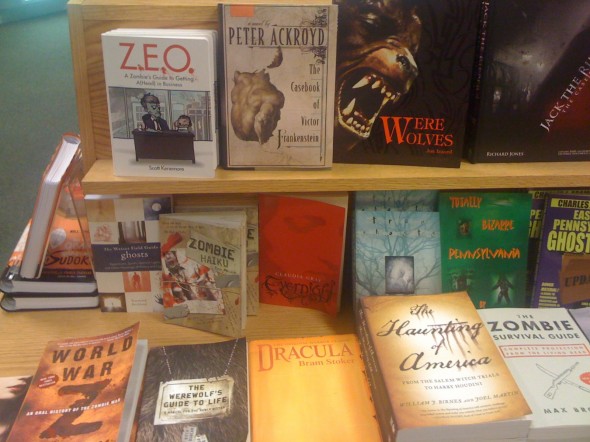

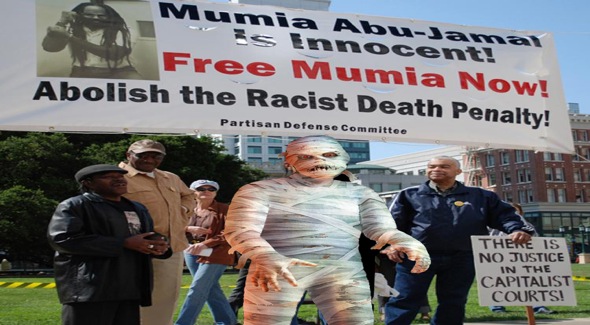

The seasonal shelf at Barnes & Noble. Lots of zombies, several vampires, a couple of ghosts, a pack of Shechner's werewolves and a Frankenstein. Where my Mummies at?

The ancient Romans, the world’s first tourists, used to visit Egypt to see the pyramids and look at mummies because those things were old. 2,000 years ago, they were 2,000 years old. Like us and Madonna, the Romans believed that the ancients knew magical secrets that we have since forgotten. We look for those secrets in the page of Dan Brown novels, but the Romans only had Virgil, so they brought home real unearthed mummies instead. Either as souvenirs in an age before site-specific shot glasses or ground up and ingested as medicine, thousands of mummies made their way to Europe and into the public imagination as something powerful, mysterious and potentially sinister.

If Mummyx causes plague, boils, frogs or the death of your firstborn, stop taking Mummyx and consult your physician.

After the Arabs conquered Egypt, the trade dried up and the European fascination with Egypt didn’t return until the end of the 18th century when Napoleon’s archaeologists found the Rosetta Stone. The 19th century was simply giddy over Egyptology. (What other country should have its own ‘ology’? Sound off in the comments.) As the fine folks at the British Museum plundered every grave they could find, Western writers recognized the inherent creepiness of grave robbing and started writing books about it.

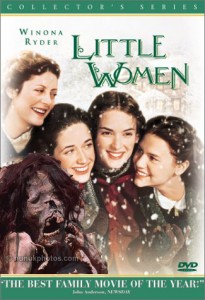

Three major mummy works of the 19th and early twentieth centuries were, in order of coolness, “The Mummy’s Foot” by Theophile Gautier (1847), Jewel of the Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (1903), and “Lost in the Pyramid, or The Mummy’s Curse” by Louisa May Alcott (1868). That’s right, in between Little Women and Little Men, Alcott wrote a short story about the undead.

The three stories basically follow the same plot: person comes into possession of a mummy or a piece thereof, mummy is not as dead as originally hoped, vaguely magical bad things happen until whatever is disturbing the mummy’s rest is put right. Moral of the story: stop robbing graves you sick bastards.

Ultimately, you’ve never heard of any of these. They’re not that good, whatever the New York Times says. Stoker’s plot cowers behind impenetrable prose, Gautier’s story focuses on his protagonist’s great taste in home décor (the titular mummy’s foot is a new paperweight), and Alcott’s most horrific moment involves deadly Egyptian flower seeds. In none of them is there an ancient, rotting corpse coming to get someone. That took the magic of cinema.

In 1922, Howard Carter discovered the previously un-grave-robbed tomb of King Tut and the world’s Egypt fetish hit an all time high. Why it took ten years to greenlight, we’ll never know, but in 1932, Boris Karloff first played an undead creature, shambling across the screen, bringing inevitable doom. He and director Karl Freund, who served as cinematographer on both Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and “I Love Lucy,” where he’s credited with developing the first three-camera sit-com, gave us many of the tropes that horror has come to rely on.

Mouth technology has come a long way since 1932.

Their story, most familiar to us from the once fun and now thoroughly unwatchable Brendan Fraser franchise, has Prince Imhotep cursed for all eternity for falling in love with the Pharaoh’s main squeeze, then killing the boss. Instead of just having him buried/eaten alive, they have him buried/eaten alive in a way that leaves open the possibility that he’ll come back with god-like powers. Say what you want about the American penal system, it has at least replaced apotheosis with a parole board.

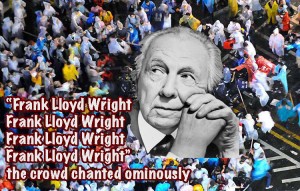

The real Imhotep was one of the ancient world’s great architects. To someone from the Old Kingdom, these movies would be like us running from a reincarnated Frank Lloyd Wright.

Having endured that harsh/stupid form of punishment for thousands of years, Imhotep comes back, as Belinkie put it, as an ancient, bandage wrapped, unstoppable Terminator whose existence means certain death for someone. Unlike a zombie, the mummy takes things personally. If you spent much of your life and fortune preparing for the afterlife, had your viscera removed and your brain pulled out of your nose, then found out that eternal life meant millennia of dust and darkness followed by grave robbers screwing with you, you might take things personally too.

So this Halloween, go ahead and put on your zombie costume (or better yet, an Overthinking It “Braaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaains” shirt) and have your fun. Just remember the wisdom of the ages, respect your elders and show the mummies some respect.

Thanks! Mummies need more representation. As (I’m guessing) the only Egyptologist/regular reader, I have just a few additions.

1) The Greeks were tourists before the Romans; there are plenty of Greek graffiti in tombs and on temples. In fact, the Hellenistic period was full of Greek-speaking tourists in Egypt, like Herodotus and Manetho, to name a few famous examples. Of course the Romans took the tourism to a new level, and even brought some nice fads like the Isis cult home with them.

2) Fascination with Egypt didn’t quite “dry up” before the 18th century; there were some really quite amusing Renaissance attempts to decipher hieroglyphs, etc. The Romans had brought plenty of Egyptian stuff home, and that wasn’t really forgotten. (For example the obelisks in Rome or Istanbul, which was there before 400 CE.)

3) The Mummy’s Foot is a pretty awesome story, which inspired a lot of spin-offs in the movies and other literature. You can find a copy here: http://www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/MummFoot.shtml It’s a good read!

Of course, there is also the Poe classic (living in Baltimore, I have to represent!) “Some Words with a Mummy” which can be found here: http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/eapoe/bl-eapoe-some.htm

I have a lot to say about the transformation of the mummy movies from including decent scholarship alongside the horror plot and moralizing, and in fact will be teaching a course during our January term about just that. Maybe I can put together a guest post for you…

@Katie – You definitely need to get in touch with us about a guest post. Anyone who can bring some academic analysis to a Brendan Frasier movie is a friend of ours. Email us at “editor AT overthinkingit DOT com”.

I’d certainly be curious to know if the ancient Egyptians had any beliefs about mummies rising from tombs to terrorize the living. Were mummies scary things to them? Or were they just dead bodies?

@Josh – I had no idea that Bram Stoker and Louisa May Alcott wrote mummy stories. Craziness.

And I would go to see the Frank Lloyd Wright horror movie. Proposed title: “Frank Lloyd Wrong.”

I totally just bought Jewel of the Seven Stars today before reading this! It was in the kid’s section at a second-hand bookshop, but it was the lurid cover art that got me.

A wrist had been pinned to the floor with a sword and was oozing blood, a cat shrieking in the background. Being by the author of Dracula was a nice bonus, and even if it’s as bad as you say I look forward to reading it.

Bram Stoker also tried his hand at, believe it or not, fairy tales for children. Think of the children!

I think you answered why mummies aren’t very popular: they come with the same story each time, lacking the openness of vampires, werewolves and zombies to other types of story and genre. Or maybe no-one’s tried hard enough yet.

You might enjoy this clip of Frank Lloyd Wright on early (1956) TV game show ‘What’s My Line’: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbZliXx8kIQ