“You are all going to make me lose my mind.

“You are all going to make me lose my mind.

Up in here.

Up in here.

You are all going to make me go all out.

Up in here.

Up in here.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman, on his “march to the sea”

From Buchner to Buschemi, from Dickinson to DMX, the modern human is oft-beset by the specter of madness. Denied the comforts of microcosmic tradition and ritual, torn from the circadian rhythms of preindustrial life, and disarmed of macrocosmic rationality or consonance, the modern human is forced by exposure, education and experience to confront paradox, treachery, nihilism, contradiction and, above all, brutality, within a paradigm that does not admit to the existence, let alone prevalence, of these things.

In such circumstances, whatever the threat without may be, the true threat is within — that your own mind and body will reject reality and rebel against your self-control, plunging you into despair or insanity.

Perhaps one day you awaken to find yourself transformed into an enormous bug.

Perhaps you find yourself in a bank, responsible for hostages you have not taken — mistaken for a bank robber, when you have done no such thing — fired at by ground- and airborne sharpshooters for the crime of banking while black, even as you save the lives of the very men looking to take yours.

It’s enough to make a man lose his mind.

Up in here, up in here.

Dog is a dog, bloods thicker than water

We done been through the mud and we quicker to slaughter

The bigger the order, the more guns we brought out

We run up in there, erybody come out, dont nobody run out

– Napoleon Boneparte on the invation of Russia

This post is about a music video. The song itself is pretty great, but it only becomes a Great Moment in Racial Discourse because of the video. Check it out:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w9FHbP2-of8

A moment for context

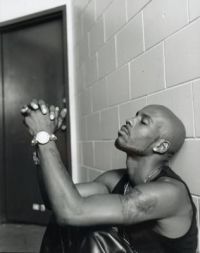

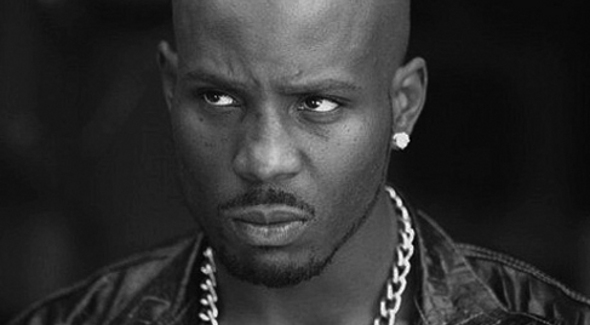

The most obvious problem the video poses before it yields to analysis is that the lyrics of the song and the events of the video seem related mostly by coincidence. However, this post will at points lean on the relationship between the video and the lyrics. As someone who tends not to ascribe to the thesis of the death of the author, this is somewhat problematic — What is the intention of Dark Man X? — but considering his Dionysian tendencies – the gutteral, instinctual element to his creative energies –- it seems fair to at least speculate as to what the significance of this art object might be were it intended as it is.

Furthermore, why should we assume the director did not consider these combinations, these tensions? We should not.

Regardless of what we assume, we can then consider the elements in parallel to the qualities they exhibit upon close reading by their own structure and details.

Context is not everything. It is important in the practical exercise of art, even if not in its serious criticisms, the possibility of happy accidents — as well as the possibility that artists happen upon or even encourage these sorts of accidents on purpose, or at least through a legitimate, if not conscious, exercise of generative creative power.

Oh, you want to know why DMX is jumping off a bank, and what this has to do with racial discourse? Read on . . .

Phenomenal post.

When you were writing this, did you notice the similarities between this video and Henry Louis Gates-gate?

@Sheely

I did not, but perhaps that is because two key factors other than race prejudice me against Mr. Gates.

A) I live in Central Square in Cambridge itself, which is a place with a lot of potential racial tension that could boil over at any moment, and in my experience the Cambridge police are ridiculously patient. The way they manage the situation in Central Square leads me to think they aren’t really out there looking to grind axes. I give them a lot of benefit of the doubt handling situations like this.

B) Being a Yale graduate, I am much more likely than the median to believe that a Harvard professor was being an arrogant jerk and disrespecting the police, and it is hard for me to feel bad when a man of the crimson is taught a lesson in humility. God knows a lot of them need it. Unlike Yale people, who aren’t arrogant at all ;-)

But yes, there are definitely similarities, and Gates probably reacted poorly because he believed he was being forced into a role where he had to.

In this way, and in almost no other way, Henry Louis Gates is a lot like DMX.

at 2:18, one of the policemen storming the building is clearly black.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re saying the DMX paradox is precisely why he raps about guns and hoes and the like? I suppose I understand the violence for violence of the video, but I fail to see why it should equate rap (theme/subject matter) for rap (theme/subject matter). By this, I mean I don’t understand how he’s forced to conform *as an artist* to other artists’ standards. I mean this in the deepest sense- clearly I understand what “sells” and that this frustrates him, but I suppose I can’t reconcile him doing what frustrates him and still think of him as an artist because it essentially means he’s selling out and then complaining about it. Basically, what I’m saying is, if he doesn’t want to be thought of as the same as other rappers because he doesn’t like what and how they produce their music, why doesn’t he just do it the way he’d prefer? He can still get the message that he disapproves out through his art without using their methods, language, etc., or he could try satirizing, like the song/video “Read a Book” by Bomani “D’mite” Armah (if you haven’t seen it, please, for the love of God, YouTube it).

@Gab –

“Correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re saying the DMX paradox is precisely why he raps about guns and hoes and the like?”

No, he just raps about those things because they are his primary interests :-)

“By this, I mean I don’t understand how he’s forced to conform *as an artist* to other artists’ standards.”

To be less cheeky, the biggest reason rappers tend to gravitate toward specific schools or styles and tend to talk about the same stuff is that rappers develop their skills and publicize themselves in direct, personal competition with each other, much more than other sorts of musicians do (except for, say, classical ones, who are all trying to play the exact same pieces with maximum virtuosity).

This competition is also, especially during the time DMX was coming up, linked socially with the very activities that DMX is rapping about.

Like, this isn’t like the Beatles singing about submarines. DMX raps about guns and shooting people before they shoot him because he tends to keep a lot of guns in his house (and has been arrested and put in jail for them), which he retains in order to credibly threaten shoot people who intend to shoot him.

DMX is chastising people not for carrying guns or making a ruckus, but for doing these things in a reckless way that comes from inexperience and not taking things seriously. By all accounts, DMX takes things like guns very seriously, and a DMX utopia isn’t a world without guns, it’s a world in which people only get shot if they really deserve it.

And the DMX paradox is that by setting this high bar — by calling out people who shoot people who don’t deserve it or who cause problems by running their mouths and getting involved in situations or quarrels they don’t understand, he puts himself at odds with these people, and because these are people with guns who will presumably shoot him, he shoots them first.

I mean, the baseline, where DMX wants to be, is not exactly a place you would identify as safe, I suspect, but to DMX, it’s still an improvement over his surroundings. Take this quote from Wikipedia:

“In June 2004, [DMX] was arrested at the John F. Kennedy International Airport on charges of cocaine possession, criminal impersonation, criminal possession of a weapon, criminal mischief, menacing, and driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol while claiming to be a federal agent and attempting to carjack a vehicle.”

This is not a guy who only does the things he does to conform or be cool. Part of DMX’s enduring popularity has been that he has generally been viewed as legitimate and substantive in his discussions about how likely he is to fly off the handle and wreck shit.

“Basically, what I’m saying is, if he doesn’t want to be thought of as the same as other rappers because he doesn’t like what and how they produce their music, why doesn’t he just do it the way he’d prefer?”

Another thing I’d mention is that this is pretty much what DMX does. It might not be obvious to people who aren’t rap enthusiasts, but DMX’s style of rap isn’t mainstream rap. He’s sort of in the direction of the rap equivalent of hard rock or metal — compare him to somebody like Biggie or Busta or Jay Z or Snoop Dogg or Nelly or 50 Cent or even Eminem, Dre or Tupac (let alone somebody who is just not even in the same solar system, like Kanye West or Mos Def), and DMX’s raps are much less melodic, much less lyrical.

The thing DMX doesn’t tend to do is add floral, baroque accoutrement to his treatment of his subject. It’s pretty rare that a DMX rhyme will land, and you’ll think it was cleverly done, not because he’s a bad or clumsy rapper (he’s not; what he does is pretty hard), but because he treats the rhyme scheme like a formal framework within which to operate, not an end in itself. He isn’t interested in appearing to be clever.

DMX likes to do a lot of his poetical work (because he is, after all, a professional poet) within lines. That’s why so many of his lines are so long – he likes to modulate the rhythm of his verses on the verbal level in interesting ways in order to lend or detract emphasis.

The classic DMX line is a line with a forced pause in a place that requires you to read it in a particular hyped up emotional state in order to fit with the established metrical structure. And while he doesn’t go for brownie points on end-stopped lines that much, he will show off with internal rhyme in order to reflect the smaller units that pop up out of his lines and pepper the rhythmic structure with his particular sort of poetical frenzy.

And here comes the triple post . . .

One thing that really amused me when I figured it out is that a lot of the that things that distinguish what I think of as “angry rap” from “fancy rap” are differences that persist across English from the Norman invasion.

That is, it wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate to refer to DMX as more “Germanic” or “Anglo-Saxon” than, say, Biggie Smalls, who would be more “French” or “Latinate.”

The difference is the difference between accentual meter and syllabic meter — English prosody exists in the middle place between these two styles that it gets from its main parent language families — Germanic languages and Romance languages.

DMX’s lines are more accentual. Extra syllables tend to spill out over the structure, but as long as the strong syllables line up in a recognizeable pattern from line to line, that doesn’t feel like it breaks the form.

Whereas a rapper with more “flow” (although I really hate that word in describing rap, because it doesn’t really mean anything credible) — a rapper with a smoother style where unstressed syllables are as much a part of the expectations for any given line as the stressed syllables are – where the stresses within words aren’t these guideposts that the rest of the work is tied to, but the lines themselves are more of a woven pattern with variation and decoration – that’s a more Latinate sort of rapper, a more French sort of rapper.

I mean, we’re all speaking English, and this rift is just hewn massively across the language over more than a a thousand years — it’s not like the language is going to change for it just because of people’s race.

But I suspect people wouldn’t appreciate this choice of vocabulary, and I have no intention of showing Mr. Dark Man X, Biggie Smalls or anybody else that kind of disrespect, so I tend to keep this sort of analysis to myself.

Oops.

But if his justification for being so violent has more to do with his own personality (i.e. being one craaaazy mofo), why complain about his peers? It sounds kind of like the Hulk, “Don’t make me angry, you won’t like me when I’m angry!” but meant in a much more hostile way. When the Hulk says it, it’s (generally) as a real warning because he *doesn’t* want to do harm, whereas with DMX, it feels more like he’s saying he’ll bust a cap over nothing because he enjoys it, like he gets pleasure out of the DMX Smash. It isn’t just that X is gonna give it to ya, but that he *wants* to give it to ya, and for the sake of giving it.

Keep in mind, I’m not saying he doesn’t live in a world wrought with violence or hardship, but now I’m wondering something new (sorry!). If he’s frustrated with his fellow rappers because they are less restrained in this environment, why give *them* a hard time and not what they react to? And I suppose this makes him just as impulsive as they are, hence the paradox… eh?

I definitely hadn’t thought about the lyrical aspect before, but now that you say so, I realize it’s there. A much different syllabic execution. Funny that, D’mite calls himself a lyrical poet.