Your children will not save you

Your children will not save you

WARNING: The spoilers pick up in this section.

Cross-generational alienation is not new to 24. We’ve all had our fill of the Bauer family by this point. Kim Bauer’s return felt tedious not long after it started, although it was a lot of fun when she caught on fire. The show crossed a lot of this territory before.

This season, though, it followed a specific theme that speaks to the anxieties of the day. There were five (one is arguable) major parent/child plotlines in this season of 24:

- The President’s husband attempts to investigate his son’s murder, while accompanied by a sort of surrogate son — a young Secret Service Agent who placates him and humors him for a time, then tries to murder him.

- The President’s estranged, treacherous daughter is briefly welcomed back into her family’s good graces shortly before she effs it all up again.

- An African military officer is murdered by his commanding general while convalescing in a hospital. His unknowing son continues to fight for his murderer.

- Bill Buchanan, Jack’s surrogate father and a shadow of his former self, asks for Jack’s help in one last mission and ends up getting killed while Jack is watching.

- Jack and his surrogate son/little brother Tony Almeida engage in elaborate quintuple-crosses during which Jack is always a step behind.

The Obama/McCain election traced a lot of fissures through American culture, but perhaps the most pronounced was generational — this was, above all, an election won by younger people (say, under 40), who consolidated disparate interest groups and got a bit of a thrill from overthrowing the status quo.

“Change” is a pretty vague word. It connects much more cleanly and directly to generational sectionalism (which changes because it must — aging is not optional) than it does to the current right/left political continuum (which doesn’t match the parties well right now), or indeed to any particular issue. Many historically conservative areas (think Iowa and North Carolina) went blue not on the force of issues, but on the force of generational politics — the young mobilizing the countryside.

And the Obama/McCain election was a war. People and materiel moved thousands of miles across the country, handled by an elaborate chain of command and directed by logistical HQs that conducted all matter of simulation and analysis, all in an effort to win.

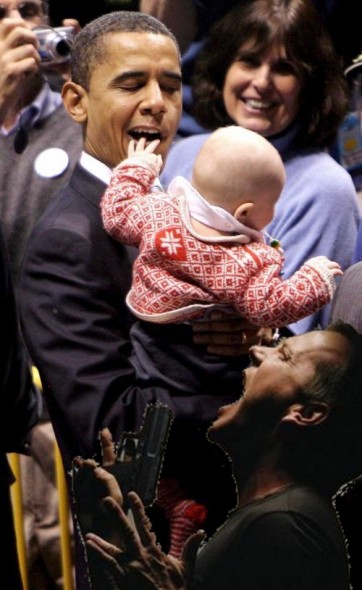

This is a very flattering picture.

Again I ask people like me to step outside themselves and consider what it is like for a parent to go to war with a child, especially if the child is powerful enough to pull off the win. Incredibly disorienting, I’d wager. Disturbing. It at once recalls mortality and the passage of time and undermines one’s one authority, self-worth and self-respect.

Now, if the parents and children were on the same side of the party divide, this probably wasn’t a problem last year, but remember that for much of the country, this was not the case. Many parents went through more than a year of political enmity with their kids.

In the Age of Obama, obedient children who support your ideals and carry through what you believe into the next generation are not going to be there — that’s the anxiety. They will take things you think are sacred, and they will destroy them, because they have grown into adults who can no longer be controlled, and because even if you could stop them, it breaks your heart to do so.

And even if they are not at war with you, the reminder is that they’re different from you. They’re separate. And it’s not coming, it’s already happened. You are going to go die at some points, and your kids will live their own lives without you. That is a more pressing concern for baby boomers at this point — facing retirement and an ascendant generation of offspring looking to remake their parents’ country in their image — than it has been for an American demographic in forty years.

It's like a Greek tragedy with flash-bang grenades.

The big cliffhanger for this season of 24 is whether Jack and Kim will survive an experimental operation to harvest stem cells from Kim and use them to cure Jack’s neurodegenerative condition (brought on by a biological weapon).

Earlier on in the season, Jack asked Kim to let him die, and I believed him.

My money is not on both of them surviving into next season, at least not unscathed. The culture war between parents and children doesn’t proceed without casualties. We no longer live in a country where children become their parents and take their place — if we ever did. Instead we live in a country where each generation revolts against the one before it, and the results are always painful.

That was how this season of 24 played it out, anyway.

History, tragedy, farce.

We seem in this essay fairly tuned-in to the myths and symbology that haunt the other. Yeah, they had a summer of love. Yeah, they were present during and not totally unaware of some sort of thing with civil rights. Yeah, the musical-industrial complex saw fit to bestow upon them an endearing range of impresarios who even now refuse to bow off the dinosaur-pop stage.

Then they got mortgages in the suburbs and cast their lot with W. It’s easy to make fun of old people. The eyes that saw Woodstock harbor their share of motes. But it may be that our fascination with the semiotics of change blinds us to the essential emptiness of our own beloved zeitgeist. When the primary argument for our current civic direction is the imagined opinion of an imagined history, can we really be headed the way we think? Having abandoned all judgment for the pleasures of marketing, will it be a surprise that we get whatever the marketroids decide? Can we turn this canny social microscope on ourselves?

To be clear, “24” is an awful show: repugnant, ignorant, and incoherent. It has no need for pacing or a narrative arc; it can just crank up the chronological sound effects. Its misguided caricature of the organs of state fulfilled its own prophecy when filtered through the insecurities of a cadre of officers and civil servants who knew well only the political calculus to which they owed their offices. The parody of governance and defense portrayed, justified, and echoed appeals only to those who have forgotten or never considered the fallibility of our natures, the impossibility of really understanding each other.

But let’s not make too much of our sympathy for those poor bastards who live like that. We live like that. We have overthrown Caesar for Octavian, and we imagine that the Republic has been revived. We know that _this_ iteration of the 8-to-12-year petal-picking cycle is special. We like _this_ circus so much more than that other one. We run from one side of our cell of civic possibility to the other, and have no concept of what might be found outside. We are all Americans.

At least it seems like that to me.

@Jess

The primary argument for civic direction is always an imagined opinion of an imagined history. Imagining that history and imagining opinions of it is one of the most important roles of storytelling in human society.

As cynical as you might get, you will never escape the zeitgeist, because the zeitgeist just becomes whatever you escape to. Whatever frame of reference you use to assign meaning to something, it will be based on an idea that at some point will pass through the lens of interpretation.

Take, for example, the War in Iraq. The War in Iraq as it broadly impacts American government and civic life, is a series of imaginations. No one person experienced enough of the War in Iraq to be able to comprehend the entire enterprise, and most of the information – even the good information – comes thirdhand. Maybe you have some amount of information that isn’t imagined, but in in this world, it will never be sufficient to inform an opinion on something as nuanced as human governance without filling in some of the blanks.

So, how do we deal with it? We do the best we can. We can try to pull ourselves out of this game, but, as Milton said and you also articulated, “New Presbyter is but old Priest writ large.” Revolutions don’t end history. Hacking off some part of the world you don’t like, given time, will usually cause something awfully similar to grow in its place – or sprout somewhere else.

So, where does that leave us?

It leaves us as the stewards of history. It leaves us to come up with the story. And that story is important, so it carries with it a great deal of responsibility. That doesn’t mean we don’t imagine – even the most honest stewards of history make their own choices about how the stories are told.

And it also means that the stories that are in play already, especially the ones that inform the zeitgeist, can’t be dismissed with just a wave of the hand and acknowledgement of their falsehood, no matter how repugnant they might be.

I understand your anger – and I share much of it. My original draft of this article had a _lot_ more vitriol directed at politicians and party politics, but I cut it in the interest of trying to stick to the point and not get sidetracked too much in the main article.

But I do think it’s important to try to understand influential ideas and trends that you don’t agree with, and not to insist they are awful and toss them aside as a rule. If they’ve captured people’s imaginations, there’s usually a reason for it, and learning that reason can make us better stewards of history.

I’m not going to go to the mat and say that 24 isn’t awful. A lot of the time it is. But I think you’re letting your own prejudices get in the way of understanding why people like it and why they connect with it. In that way, you are the one with the imaginary opinion (that there’s nothing defensible about 24 that anybody could like) about an imagined history (in which 24 wasn’t a really popular TV show that can be a lot of fun to watch).

But, if 24 teaches us anything, it’s that we all become what we despise.

I think 24 appeals to a lot more people than you do.

I’m not trying to refute you – I think a lot of what you say has merit, and I’m curious, but I want to establish a bit of a framework for where I stand here in relation to what you’ve said.

You say our zeitgeist has “essential emptiness” – in your opinion, is this especially desirable or undesirable, and, if undesirable, what would it take to “fill” it?

Thanks for reading, and I hope you at least enjoyed the photoshops :-)

If you didn’t hav time, you should have just gone for one:

“Tell me where the tags are!”

@fenzel …Jesus, man. That was way deeper than I thought 24 could go. I definitely saw the struggle against Obama Nation in this season, especially when Janeane Garofalo talked, but YOU. You are the man.

Oh, and since you mentioned the photoshops, I love Jack Bauer screaming at the world.

@Fenzel: Thanks for the thoughtful response. I would have responded earlier but was traveling.

First of all, let’s stipulate that I appeal to very few people.

My “To be clear” paragraph was intended as a digression. I do feel that “24” is bad in a bad way, but only thought it necessary to say so because it seemed to run counter to my other thoughts. My main point was that your essay seemed to associate “24” with the old folks who didn’t vote for the epochal change that is Obama, to their mutual discredit, and to counter that nothing has actually changed, IMHO. I thought maybe you were making a bit more of your differences with the conservative masses than could be supported, although your subsequent comments have ameliorated those concerns somewhat.

(Another digression: I also know a number of Obama voters who are ardent “24” fans; I’m not sure where they fit into this analysis. Perhaps they are sophisticated enough to enjoy the carnage on an ironic level, much as hip-hop artists have largely appropriated the n-word for their own purposes.)

I don’t mean “nothing has actually changed” in a trivial “plus ça change” sense, but in the sense that we having been making really terrible public decisions for decades now, and now that we’ve had an election we are still making those terrible public decisions only more so. I no longer believe our system is capable of avoiding these decisions, so I focus more on coping strategies than fighting the good fight. At the same time I’m not exactly inspired by the whole mess, and I feel a bit of pity for those who are.

I may be stodgy in thinking that the marketing narrative shouldn’t govern all our decisions, or cluelessly nostalgic in thinking it hasn’t always done so. I’ll cop to both. I’m left with this: that our public choices are directed by those who have positioned themselves to profit thereby, at the same time that the mass of the public swallows the asinine fake-conflict pap that gets written about it in the papers. (“freedom v. security”, “fairness v. capitalism”, etc.) I could deal with the corruption, if just occasionally someone else acknowledged it. I normally cope with even this grim conceptual situation; maybe there’s something about the erudition of OTI that slips through my practiced indifference and prompts me to write really long comments.

Upon reflection I see that I am guilty of a bit of clumsiness here, because you’re mostly describing the reaction of “24” and its worldview to a perception of Obama rather than describing Obama himself in any concrete way. That is in keeping with OTI, and I can’t really criticize it. Clearly Jack Bauer the character would draw a distinction between W and O. Both W (or his minion/regent Cheney) and O would publicly claim a sea change between their administrations, and I should accept that as a context in which a popular television program can operate.

Events have also overtaken me a a bit in the sense that Obama has made more specific his plans for closing Gitmo. I applaud this and any other plans for our government to obey the law, but I wonder if I too am distracted by a sideshow. After all, the NSA is still bcc’ed on every single email sent in this country. The national public debt is still hockey-sticking. Hank Paulson isn’t in prison yet. I could go on, but I probably shouldn’t. Thanks for the interesting exchange.

To answer your questions: I do object to this particular zeitgeistian emptiness. I don’t think it can be filled without a great deal of real change in our governance and lifestyle, so it isn’t clear that filling it is something that most people would choose even if they were aware of the option.