Back in the fall, Wrather wrote an excellent series of posts on Gossip Girl in which he analyzed the literary, psychological, cultural, and socioeconomic aspects of the teen soap opera. However, six episodes into season, it seemed that the show’s second season was going to be a huge disappointment and that the exploits of Serena, Blair, Chuck and company were simply not deserving of that level of scrutiny. As a result, the project fell by the wayside. Since then, the series has not only supplied ample guilty pleasures (including girls going wild, drunken rooftop-ledge shouting matches, and illicit teacher-student affairs), but has also provided substantial food for (over)thought, most recently on the philosophical bases of punishment and the relationship between the police power of the state and economic elites.

Of course, this is Gossip Girl, not a political theory textbook, so these philosophical and sociological ideas are embedded in plotlines that focus on a variety of romantic entanglements, scandalous revelations, and boatloads of deceit and double-crossing. The latest batch of melodrama, which came to a head in last week’s episode, revolves around the revelation that Serena’s new boyfriend, Gabriel, and new best friend, Poppy Lifton, are not the southern Tobacco heir and socialite that they purport to be, but are actually con artists whose aim was to rope Serena’s mother Lily and the other multi-millionaires of the Upper East Side into a Madoff-esque Ponzi scheme.

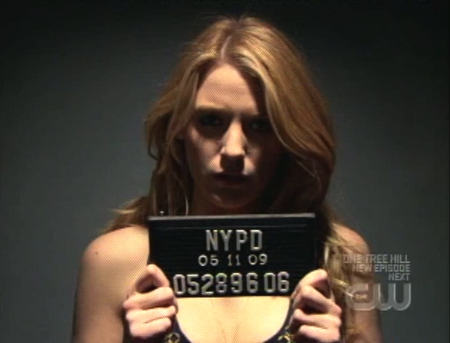

Once Serena learns that Poppy is the mastermind of the operation, having grabbed all of the money and left Gabriel in the lurch, she and Lily disagree strongly about the wisest course of action. Serena wants to enlist Chuck and Blair in an elaborate operation to catch and humiliate the Poppy, whereas Lily wants to just pay off the other investors out of her own fortune to avoid a public scandal. When Serena goes forward with her plan, Lily calls the cops with the false report that Serena has stolen a piece of jewelry from her, scuttling the revenge plot and allowing Poppy Lifton to flee the scene.

On the surface, the conflict between Serena and Lily appears to be a dispute between deontological and consequentialist theories of crime and punishment, with mother and daughter disagreeing about whether the right course of action is to ensure that the grifters get the punishment that they deserve or whether the desire for retribution should be secondary to the rational calculation of whether or not punishing Poppy causes more harm than good. Throughout the episode, Serena is a stubborn retributivist (unknowingly carrying on the tradition of Kant and Hegel), constantly asserting that to let Poppy Lifton escape would be fundamentally unjust and that the morally right course of action is not only to punish her but to actively collect evidience that proves her guilt. In contrast, Lily is much more of a utilitarian than her daughter; she argues that the costs to the family’s reputation and Serena’s future are too great to make punishing Poppy worthwhile and that the better course of action is to let Poppy escape and just pretend that they were never conned.

However, there is also a fundamental similarity between Serena and Lily’s actions in this episode– both ultimately use the language of justice and the related institutional arms of the state to pursue private aims. Serena and company were prepared to call in the police to arrest (and, in the process, humiliate) Poppy Lifton after they had recorded her conning a new mark, but Lilly trumped this by using the NYPD to prevent Serena from executing the counter-con. Although they were working at cross-purposes, both plans are rooted in the premise that the police are not be autonomous arm of the state so much as they are a tool that the wealthy can use as they see fit.

Viewed in this way, the disagreement between Serena and Lily is more a matter of differing time horizons than opposing value systems. Serena (and the other Gossip Kids) typically care only about short-term vengance; their scheme to con the con-artist (much like most other Blair/Chuck-driven schemes) is an aristocratic duel in which the weapons are cell phones rather than pistols . In contrast, Lily’s restraint stems not from adherence to a competing moral code, but rather from a different frame of reference; rather than caring about avenging one particular wrong, her focus is on protecting Serena’s future and the family’s reputation. Last night’s 80s flashback episode (and spinoff pilot) revealed that she didn’t always behave in this way; when she was a teenager, Lily was as myopic as Serena, whereas her mother was the one concerned with protecting the family’s reputation and social standing.

This simultaneously self-centered yet forward looking world view explains why she (and the other adults) in the fictional Upper East Side behave differently from their children, even if that behavior could hardly be called “mature,” “wise,” or “moral” in any conventional definition. Although the grown-ups are just as likely as their offspring to act like impulsive, selfish, horny teenagers, the main difference is that the “adults” take steps to ensure that their childish actions guarantee that their entire lineage will be able to act with impunity in perpetuity.

Sheely, this is all brilliantly observed and and analyzed. Here are a few observations:

1) The 80’s GG spinoff may be dead: http://www.deadlinehollywooddaily.com/that-gossip-girl-spinoff-dead-at-cw/

2) The worldview in Gossip Girl is blatantly aristocratic. It doesn’t even pull its punches. Dan comes in for non-ironic ridicule when he takes a job as a cater-waiter, the implication being that he’s a class traitor, or else never belonged in the aristocracy to begin with.

3) Gossip Girl sees membership in the aristocracy as a matter of essential worth — an intrinsically better class of person — rather than as a benefit conferred by hard work or even luck. The social order — which, with its hierarchical arrangement, smacks of feudalism — is objectively ordained.

4) I think this accounts for the view of the police not as an autonomous arm of the state serving public aims but as a private instrumental force serving the private — indeed, not just private but personal — aims of the aristocracy. The police — and, by extension, the law and the norms of society — may govern everyone else, but Serena, Blair, Chuck, etc. are above that.

5) Is there an inconsistency here? The show seemed to suggest that there was a moral imperative for Nate to turn his father in for securities fraud, meaning that it was right for the father to be subject to the same laws as everyone else.

5a) But recall that Nate’s dad is not the Vanderbilt; his mother is. In a way, the father’s business failure and subsequent resort to fraud is seen as evidence of his intrinsic unworthyness.

6) Serena’s focus on retribution is a convincing characterization, since it accords with the developmental psychology of adolescence, viz. newfound (and thus zealous and absolute) devotion to abstract ideals like fairness.

7) There is a lack of faith in social institutions that I think goes beyond the aristocracy’s viewing the police as simply a private paramilitary force. Serena and Blair often see themselves as the only force that can right a perceived imbalance in the world. Part of this is due to Belinkie’s First Law of Kids’ Movies — in its most Derridean formulation, “All minors are always already unaccompanied.” — http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0488658/ and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYhbQ4Xvdvk (q.v.).

But there’s more to it than that. I think that these kids understand that when you live outside the law you forfeit its protections.

@Wrather- I’m glad that this post could, at the very least, get you writing about GG again. I think any of your points could (and should) be expanded into a stand-alone post.

About the 80s spinoff- I’m not sad that this is dead. Based on what I saw in last night’s episode, it just didn’t work. In fact it was so off that it made me even the weakest GG episode seem great by comparison. It was pretty deeply flawed across the board- the writing, casting, acting, and production design just were not at the level of the original.

There is nothing metaphysical or Dostoyevskian about Gossip Girl. Nothing at all. Though it was not a poor attempt to establish philosophical means within a teenage soap opera; espeically one as deep as bathwater.

I’d like to see more of how your mind works but in the mediums of music and films, rather than the world of nothingness that is Gossip Girl.

@Shane- Thanks for reading. For more on how my mind works (and treatments of similar themes in the context of other media), click through to the posts on Kanye West/Robocop and Black Sabbath’s Neon Knights, or click on my name at the top of the article to see my full list of articles.

In terms of the contention that Gossip Girl lacks sufficient depth for overthinking, I would tend to agree that there isn’t necessarily much that is Dostoyevskian about GG (of course if any of y’all do see Dostoyevskian themes in GG, please chime in). The “Crime and Punishment” allusion in the title was more a reference to Beccaria’s treatise on criminal justice and the related literatures in both Criminology and Applied Ethics. From this perspective (and from a broader sociological perspective), I think that there is frequently much more to the show than meets the eye.

Of course, I’d also be lying if I said that I watch the show for purely intellectual reasons. I started watching the show about a year ago (halfway through season one) because my fiancee is a fan, and got sucked into because it is often quite funny and occasionally well scripted and acted. In particular, the performances by Ed Westwick and Leighton Meester (Chuck and Blair) alone place it on a level apart from many other teen soaps.

“… more a reference to Beccaria’s treatise on criminal justice and the related literatures in both Criminology and Applied Ethics. From this perspective (and from a broader sociological perspective), I think that there is frequently much more to the show than meets the eye. ”

Point taken.

I’ll check out your other works. Good work!