Movie junkies suffered a crippling blow to their understandings of the universe this week. If you put your ear to the ground in Hollywood, you could feel the vibrations as the Earth shifted to accommodate it.

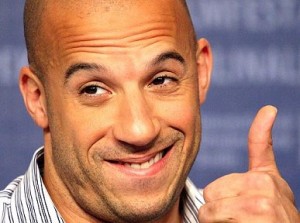

As of this writing, Vin Diesel’s IMDB STARmeter is up 600%, week-over-week, and the entertainment windmills are spinning like industrial fans.

Fast & Furious made $72.5 million last weekend. That’s the largest April opening weekend ever. It’s the largest opening for a movie about cars ever. It’s the largest opening weekend of the year, annihilating pretenders like Watchmen and Monsters vs. Aliens. These are summer blockbuster numbers, people — and we’re not even in finals season yet.

Thankfully, Overthinking It is here to help you sort through the madness with a little philosophy about this strange world it turns out you’ve been living in all along — this world where Vin Diesel is a huge movie star —

Why Did You Ever Doubt Him?

When you come across an event or fact that defies your explanation of the world, the natural urge is to nudge your explanation of the world enough to fit in it. Contextualize it. Narrativize it. Give it a story and a place. Adjust your idea of the world to accommodate the new piece of information.

A bunch of folks in Hollywood are no doubt doing this right now. Clearly, Vin Diesel speaks to an underrepresented +18 male demographic that is not as enchanted with comic book adaptations as we thought. Clearly, American moviegoers crave multiracial heroes and fantasies about conspicuous consumption.

Clearly, Vin Diesel was always a huge movie star, and he just didn’t make a lot of movies in the last couple of years, since he’s been spending a lot of time stuck in development and raising money so he can act in and direct Hannibal the Conqueror.

(As I often say, in any sort of argument, “clearly” usually means, “I really think this is true, but I’m not going to provide any evidence of it.”)

Actually, take a moment to let that Hannibal part sink in. Check out the directorial credit on this page. That’s written by the guy who wrote Gladiator and Amistad. Truly, there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Anyway, for most people (and indeed for this site 99% of the time), retroactive explanations are not only enough, they’re what we go for. We all go through life looking in the rear view mirror, and just because it’s not perfect, that doesn’t mean it isn’t the way things work.

But I want to take a moment to invoke my favorite book of the decade so far, Nassim Taleb’s The Black Swan.

A Fast, Furious World

The Black Swan is about how history and the world are mainly and increasingly shaped by unlikely twists that nobody can ever successfully forecast. The more we think we know what will happen, the more we will be sideswiped by what will actually happen, which will probably be crazy!

One of the book’s early supporting details is that people are really good at coming up with explanations after the fact that they would never be able to offer before something happens, and that this way of thinking is worth a lot less than we think it is.

Not Vin Diesel. Probably wishes he were Vin Diesel.

After Spider-Man, it’s obvious that comic-book movies straddle very fortuitous demographic dynamics, have built-in, pre-sold audiences of loyalists, and can make for great summer blockbusters. After The Lord of the Rings, three-and-a-half hour movies are clearly justified for theatrical release.

After the hundreds of millions of dollars are in and counted, those movies became mainstream signposts. People forget that their successes were far from foregone conclusions, and that you had to get gloriously crazy horror movie visionaries to venture so far from the beaten path to make them work in the first place.

Accepting retroactive explanations for phenomena is philosophically lazy, because such explanations rarely resemble the world as we experience it or faithfully describe the mechanisms of causality.

They imitate it, they reflect it back to us, but they don’t show up until the present moment has moved on, and since all of history is a myth, they’re myths as well (I’ve ventured pretty far from The Black Swan by now, but bear with me). We the living must exist in our moment, as Frost said, a present “too much for the senses, / Too crowding, too confusing- / Too present to imagine.”

2 Fast 2 Furious

This, by the way, is why I always scoff at scientific evidence that begs the questions of free will or consciousness by introducing some mechanism by which to demystify them. Explanation and experience are different animals, and finding the reason the sun rises doesn’t change the fact that you have to get up in the morning. So, whether it works or not, it’s still just a retroactive explanation.

On history as myth: Every once in a while, I think about a historical person whom I can imagine with clarity, like, say

Abraham Lincoln, or the world that surrounds that person; the three-piece suits, the absurd mustaches, the tattered blue and gray bloody shirts waved by politicians, and I muse as to where it is. I can imagine it as vividly, or more so, than Dubai or New Jersey or any number of other real, fantastic places.

But Lincoln’s America isn’t real anymore. It exists only in our imaginations and records, not in the memory of any living person.

Consider Carl Sandberg’s “Cool Tombs.”

Now, consider Fast & Furious:

I have to say, the movie looks pretty awesome, and I love the big reveal on who’s driving the car. Haven’t seen it yet, but I can definitely understand the retroactive explanation that this movie was always going to be a huge hit and Vin Diesel’s star power has been consistently underestimated. And I’ll probably eventually catch it on DVD or video on demand or something.

Maybe I’ll have a Fast, Furious movie marathon and Tokyo Drift all over my house until my roommates tell me I’m too loud and I need to go to sleep.

Lessons

As you can tell by now, I’m a bit less concerned than Taleb and his Black Swan are with the pragmatic consequences of the prevailing unknown, but they bear mentioning. Remember that you don’t really know what’s going to happen. Make business and career choices that put you in a position to benefit from large, unexpected events rather than leave you vulnerable to them, because they will happen, and you don’t know what they will be.

I also feel a bit vindicated personally, because my explanations for Vin Diesel’s star power are not entirely retroactive. I’ve liked the guy’s work for a long time, and I’m less than half-joking when I recommend that people at least watch The Chronicles of Riddick. But that’s not really the point. I got lucky this time. I’m sure I’ll get my comeuppance when Hannibal the Conqueror turns out to be a huge travesty or something. I don’t intend to let myself get cocky over this.

Diesel, but no Vin Diesel.

Still, did people think that the only guys left who could carry action movies were Oscar-hunting method actors, quirky offbeat character actors, 60-year old men and Jason Statham? Really?

The most basic lesson from this is that Vin Diesel is probably going to get a lot more work, and Hannibal the Conqueror is probably going to get made. Of course, you never know, but it seems more likely at this point, which is great news as far as I’m concerned.

But more importantly, there are lessons here regarding how to confront the future, how to treat unexpected change in your own life, and how to think about the way the world works.

While my heart is far too out on my sleeve for me to be a true stoic, I think there is real wisdom in stoicism that can help with confronting and coping with any large, unexpected event. There is wisdom in lining up your expectations for the world – and heck, also your moral will, or prohairesis – with the way the world actually works. It leads to relatively fewer nervous breakdowns.

So, recognize that the world is crazy and unpredictable, and that F. Scott Fitzgerald was wrong when he insisted there were no second acts in American life. He probably insisted there were no fourth Fast & the Furious sequels either.

As in Zeno invoking the simile of Cleanthes, if you’re going to be a dog tied to a cart, would you rather be trotting alongside it nicely, or be dragged?

BONUS — The five stages of Diesel

If you happen to still be in the throes of grief because your worldview and personal identity rely on celebrity worship circle that doesn’t invite Mr. Diesel into their number, here’s your five-step prescription:

1. Denial — Pitch Black

2. Anger — Knockaround Guys

3. Bargaining — Boiler Room

4. Depression — Babylon A.D.

5. Acceptance — xXx

Seriously though, if you’re sad, just watch The Iron Giant. I mean it.

Vin at his most Diesel.

I haven’t read the book, but can the behavior of millions of Americans really be described as a “black swan”? September 11 was a black swan – an unpredictable event that has an enormous impact. But when a movie turns out to be roughly twice as popular as expected, isn’t that just poor market research? Just because we didn’t predict that big opening weekend doesn’t mean we need to throw up our hands and say, “It was inherently unpredictable.” Improve your polling, and you improve your predictions. Right?

@Matt –

To answer your first question, yes. The Black Swan is closely related to the Tipping Point – large groups of people are entirely capable of quickly and dramatically getting behind very surprising courses of action.

The American housing bubble had black swan properties – American housing values had never fallen before, so nobody believed they could fall. Their eventual fall, while perhaps not as “surprising,” and certainly not totally unexpected by anybody, was still largely influential because of how few people actually thought it was going to happen – or at least who processed it and its implications. And that whole trend involved the simultaneous and interrelated actions of hundreds of millions of people.

And the market research note only really troubles you until you realize just how bad all forecasting is – and also how the more faith you place in forecasting, the more your mistakes matter.

If your job was to predict which movie was going to do the best this spring, you were 100% wrong. No matter how close you got to other answers, you failed at your job completely.

Of course, professional forecasters won’t say this. They’ll point out their successes – that even though they almost always get it wrong when it’s important, they get it wrong more than would just be luck. Taleb’s solution is to basically throw those people into the ocean, because by pretending they are able to do something they are entirely incapable of doing (which is to provide reliable forecasts), they do more harm than good. People make a lot of choices based on these forecasts, and when these forecasts turn out to be wrong, they look pretty stupid.

This isn’t the same as the event being random or totally “unpredictable,” since sure, it’s not outside the realm of imagination, but if the prevalence and influence of these sorts of events overwhelms the prevalence and influence of the events that do happen according to plan, then it’s pretty much the same, pragmatically speaking, as if everything were really random.

Don’t get caught up in the aesthetics of freak accidents. Things that look really boring can actually be very unlikely or unpredictable.

And yeah, if you aren’t as drastic about it as Taleb and want to keep these people around, go ahead and try to improve your methods. But if you’re making decisions based on that information, try not to listen to the forecasters too much.

It seems like what Taleb is basically saying is that no one should even try to predict how movies will do at the box office, since they are often wrong. But this is silly. What’s the alternative for movie studios trying to run their businesses? Go with their guts? Throw darts at a dartboard? Just because the predictions are often wrong doesn’t mean they aren’t useful and necessary. It just means the movie business has a high degree of uncertainty associated with it, and you shouldn’t act like it’s a science.

You say that if your job was to predict what movie would do the best this spring, you would be a failure. But that wasn’t anyone’s actual job. The actual job was to predict how much EVERY movie would make, and I’m betting most of the time, they were in the ballpark. Certainly, their predictions were probably a lot closer than mine would have been.

It’s easy for Taleb to smirk at Fast & Furious and say that all forecasting is dumb. But just stop to think about how “The Black Swan” found a publisher. The publisher knew the marketplace, knew the success of similar books, and made a prediction about how Taleb’s book would do. Doubtlessly, that publisher is often wrong. Perhaps he was wrong about how successful “The Black Swan” would be. But it seems to me that if all the forecasters were “thrown into the ocean,” virtually every industry would grind to a halt.

Belinkie – I think at this point you’re ascribing to Taleb a view he doesn’t hold.

Taleb’s point (or, of the several he makes in The Black Swan, the one I find interesting) is that the “just-so” stories we invent AFTER unpredicted events to rationalize them are largely B.S.

So, if Taleb were addressing the box-office success of Fast & Furious, he wouldn’t be saying that “all forecasting is dumb.” He would be saying that our attempts to RETRO-cast – to explain the success of Fast & Furious ex post facto – would be dumb.

All that being said, I remain pretty skeptical of the pop summations I’ve seen of Taleb’s theses. But I’ll have to check out The Black Swan myself to address them in more detail.

@Perich –

Okay, so Taleb “would be saying that our attempts to RETRO-cast – to explain the success of Fast & Furious ex post facto – would be dumb.” But he doesn’t mean that there’s no point in discussing why Fast & Furious is so successful, right? Because clearly, there must be reasons; it didn’t make all that money by mistake.

What Taleb is saying is that we shouldn’t be too harsh on the forecasters, because the success of the movie was caused by a confluence of factors too complicated to predict ahead of time. Right? We can go ahead and figure out why it succeeded, but we should NOT assume that this was obvious at the time.

So while my impulse is, if our models had been better, we would have correctly predicted the box office, Taleb says that no matter how good your model is, there will be things that defy it.

I’m not sure I agree with this. I STILL say that if our models had been better, we would have correctly predicted the box office. Fast & Furious isn’t an earthquake out of the blue. It’s not an act of God. It’s a movie – if it surprised us, it’s just because our polls undersampled cellphones, or urban neighborhoods, or weighed the poor performance of Tokyo Drift too heavily.

I just don’t see WHY Fast & Furious COULDN’T have been predicted. Just because analysts got it wrong doesn’t make it a black swan, does it?

– Matt

Taleb is never saying that we “shouldn’t be so harsh” on anybody. He’s famously abrasive to people who disagree with him only slightly.

Taleb would probably have a problem with how the modern studio system makes movies – he’d probably much prefer either the old-school studio system or the porn industry. Picking 100 movies and sinking tens of millions into each one, including marketing, is stupid, because if any one of them fails, that’s a huge problem, and if one of them really succeeds, your limiting your upside with all that upfront cost.

He’d say the real money is in making movie like _The Blair Witch Project_ or _Slumdog Millionaire_ – movies that cost very very little, but make lots of money.

The proportion of money you make from a really expensive idea that catches on is so huge that you’d be dumb to put your money on movies that have a higher potential to lose money and can never really blow up.

He’d say if you’re investing in making movies, you should put most of your money in something super, super safe (like, say, restaurant equipment training videos, which you can sell for a reliable price), and then have a bunch of play money that you spend on long-shot bets.

In the long run, the long-shot movies will pull in better alpha than that same movie applied to tentpoles or blockbusters.

Unless, of course, the math doesn’t work out that way, in which he pretty much just makes porn.

And yes, if you took away (deeply flawed) forecasting, a lot of industries would grind to a halt. But a lot of industries grind to a halt anyway because of (deeply flawed) forecasting. So it’s tough to say whether changing tack in a larger sense would be a net positive or not.

One thing to remember about Taleb, though, is that he’s a trader – he doesn’t really care about what works for “everybody,” and a lot of his writing works under the assumption that the world is going to have big winners and a lot of losers.

So, yeah, getting rid of the forecasters makes a lot of people losers, but relative to the people who don’t rely on them, those people are big losers anyway – they’re just don’t put two and two together and realize how much they fail relative to people who take advantage of Black Swans.

Wow, LOTTA typos in that comment. Sorry, guys!

I think the main thing to remember about Taleb – to really boil it down – is that it’s not whether the forecasts are right or wrong – it’s the _relative impact_ of when a forecast is right or wrong.

When a forecast is right, not much happens.

When a forecast is wrong, there’s often a huge shift of one sort or another that you want to be in a position to take advantage of.

And he says that, for most things in the world, the effects of the latter are so huge as to render the former relatively worthless.

Q-Q-Q-Q-Q-UAD POST!

Also, Matt,

Taleb addresses one of the points you brought up – things you could concievably predict vs. things that you couldn’t – when he talks about randomness.

There’s pure randomness, where something doesn’t have a cause and is just totally out of the blue. This doesn’t _really_ exist, but we all sort of understand what it is.

Then, there’s randomness where there is a perfectly good reason for something, and from the right perspective it’s not random at all, but from _our_ perspective, we can’t or don’t spot the causes that make it happen, at least in advance.

Taleb basically says that, from the point of view of people actually living in the world, the randomness of these two different types of events is equivalent. It doesn’t matter whether there’s a good reason why the Vin Diesel movie outperformed all the others, if, within the framework we had before it happened, there wasn’t a reason to believe or expectation that this was going to happen, then it’s random.

It’s sort of like causes happen behind a curtain, and then the effects are revealed to us. We can retroactively explain the cause of something so that it is no longer random, but before it reveals itself, when we still can’t see what’s behind the curtain, there’s a lot more effective randomness in the world than our explanations let on.

Mmmm, stoicism. Your Cool-o-Meter points have skyrocketed, Fenzel. Relevant Marcus Aurelius quote:

“Things themselves cannot take the least hold of the Soul, nor have any access to her; but the Soul alone deflects and moves herself, and whatever judgments she deems it right to form, in conformity with them she fashions herself the things that submit themselves to her from without.”- _Meditations_, Book V, xix. And in Book VI, xvi, he says, “…Fluxes and changes perpetually renew the world… In this river of change, which of the things which swirl past him, whereon no foothold is possible, should a man prize so highly?”

So to be totally redundant, the stoic way of dealing with the weekend numbers is to go with it and accept the universe as it is. Don’t fight the current, let it carry you. The soul deals with things as they come, and she molds herself to fit what comes her way. A RETROACTIVE thing- she’s mutable, adaptable, so don’t try to root yourself down, since it’s impossible to do, anyway. And don’t get attached to stuff, because it’s all just shadows and dust.*

Here, “stuff” is our preconceived notions of how the market w/should work as according to the “common sense” explanations of pollsters. So the movie made a lot of money and we (meaning the masses, the public, the sheep) weren’t expecting it. Why should that *really* upset anybody? Unless you’ve got some personal grudge against Vin Diesel (or, I’d argue, anyone/thing involved in the production, from the company to the caterers) and thus a personal reason to want it to fail, there really isn’t much reason to get in a tizzy about it. And even then, this is rather un-stoic, too, since it makes you emotionally attached to the idea of their failure. The very idea of taking something “personal” is quite un-stoic.

Now, it can be argued that there are instances where running with a bad prediction leads to disaster (investments come to mind, as does bandwagonning with politicians that end up losing), so the idea of going with the flow and letting it fall off your shoulders is harder to swallow. After all, it’s human nature to get upset if taking bad advice leads to, say, bankruptcy or the death of a personal career; but the very attachment to these things is part of the (and thus your, whomever “you” may be) problem from a stoic perspective.

I’m not 100% sure what Aurelius, Epictetus, et. al. would think about pollsters. I venture to guess they’d say it’s okay to take advice from pollsters and predictions, but it’s NOT okay to let ourselves become undone if those predictions turn out incorrect. And we should be taking that advice in order to be better global citizens and work toward the Good (Virtue) and all that kinda jazz, not out of any material desire for ourselves (and if there *is* personal material gain, that should be put toward the Good or be a secondary benefit of some kind and NOT our main goal- the icing on the cake, if you will).

*The “[f]luxes and changes” part also relates to the shifts mentioned ^up there^ when an “unexpected outcome” or whatever occurs. Life is indeed a river of change, so we shouldn’t get attached to our current (HAH!) state- things will not be like this forever. We should accept whatever changes we find ourselves faced with and move on to the next bend. Also, implicit (first line) is the notion that outside forces only get to us (in the emotional sense) when we let them, that it’s up to us whether or not we get upset over something.

(That all probably sounded like a whole lotta nothin’, but I totally geeked out when I saw “Stoicism” as the first word in the title, and had to do something about it. Sorry.)

Great evaluation of Vin Diesel’s career past,present & future! Anyone who has eyes & a brain can see he’s a great actor!

@Pete –

See, I get skeptical when an armchair tycoon like Taleb starts talking about how an entire industry’s business model is dumb, and they should really be doing something completely different. Because Hollywood always makes money. A lot of money. Now admittedly, they will produce a huge flop and lose some money on that. But for the most part, studios do just fine. The studios do a lot better than, let’s say, investment banks, retail, real estate, etc.

And let’s keep in mind that the example that started this whole thing, Fast & Furious, was a movie that did way BETTER than it was supposed to, not a movie that lost them millions. It doesn’t prove that they don’t know what they’re doing, anymore than the surprise success of Tickle Me Elmo proves that Tyco should quit the children’s toy business, because their predictions are faulty.

So Pete, I’m curious if you agree with what you imagine Taleb would say about Hollywood. Is producing movies like Fast & Furious stupid? Should they never spend money on anything over 20 mil?

– Matt

I firmly believe the enjoyability of a Vin Diesel film involves the following equation (stupid math degree ;P):

Let all variables have a lower limit of 0 and an upper bound of 10:

Let W = the amount of action in the film

Let X = the amount of VIOLENT action in the film

Let Y = the minutes of screen time devoted to the Diesel in a non-speaking action sequence

Let Z = the minutes of screen time devoted to the Diesel talking

Let A = the awesomeness of the movie, determined by the other variables; the higher the score, the better the movie!

W + X + Y – Z = A

Rule: If Z > Y, then A will be a negative integer, regardless of the values of W and X.

Of course, this does nothing for predicting box office results, since really great Diesel movies like the insanely awesome Pitch Black made far less than Fast & Furious.

But I think it holds up well when it comes to the various Diesel properties; xXx got infinitely better AFTER that horrible monologue into the camera early on; Riddick seldom talks, making Pitch Black, Chronicles of Riddick and the Butcher Bay video game instantly great; A Man Apart has the Diesel on a violent bender with, again, little talking; The Fast and the Furious and Fast & Furious both have Paul Walker chewing the screen, which normally would make a movie bad, but by keeping Diesel in mainly action-y moments actually has the reverse effect =)