[Returning guest writer John Perich takes on literature and video games today. Leave your reactions in the comments. —Ed.]

“Who was he?”

“John Galt was a millionaire, a man of inestimable wealth. He was sailing his yacht one night, in the mid-Atlantic, fighting the worst storm ever wreaked upon the world, when he found it. He saw it in the depth, where it had sunk to escape the reach of men. He saw the towers of Atlantis shining on the bottom of the ocean. It was a sight of such kind that when one had seen it, one could no longer wish to look at the rest of the earth. John Galt sank his ship and went down with his entire crew.”

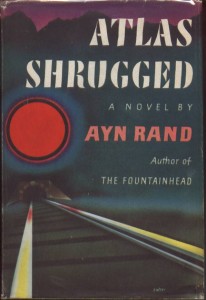

—Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand

“To build a city at the bottom of the sea: insanity. But where else could we be free from the clutching hand of the parasites? Where else could we build an economy that they would not try to control, a society they would not try to destroy? It was not impossible to build Rapture at the bottom of the sea. It was impossible to build it anywhere else.”

—BioShock

BioShock shattered critical expectations when it debuted in August 2007. It received some of the best awards of any first-person shooter videogame that year, or ever: 10/10 from Electronic Gaming Monthly, Eurogamer, Game Informer and the Official XBox Magazine. Not only was it the sort of engaging, tactical gameplay you’d expect from the makers of System Shock, but it boasted a vivid and breathtaking setting—the underwater Art Deco city of Rapture—and an original score worthy of a classic horror film.

But even with all this, BioShock would have stunned audiences for one point alone: it’s a video game that makes you think.

Ken Levine, head writer and creative director of BioShock, made explicit the inspiration behind the game: Ayn Rand’s 1957 doorstop of a novel, Atlas Shrugged. Atlas Shrugged depicts a world whose creative minds have fled, leaving society to collapse into self-destructive anarchy, and who build a cloistered paradise for themselves. BioShock depicts a cloistered paradise full of creative minds, and the problems that turn them into paranoiacs, murderers and mutants.

Hundreds of pages could be written about the philosophy that inspires Rand’s novel—and have been—and you could probably fill another hundred pages on BioShock‘s playability as a first-person shooter. But we’re narrowing our focus today. This article will compare Atlas Shrugged to the video game it inspired, to see what was similar and what was left out.

A word on SPOILERS: I will spoil significant portions of Rand’s novel in the following article. I think this is only fair—it’s been out for 50 years, you can study it in school, it’s part of the American culture. However, I will try my hardest not to spoil the crucial elements of BioShock‘s plot. I’ll tell you nothing you couldn’t learn in the first hour or two of gameplay. However, we may spoil more of the plot in the comments later on, so be warned.

“I AM GOING TO STOP THE MOTOR OF THE WORLD.”

Atlas Shrugged takes place in the very near future—the day after tomorrow. The giant corporations that turned the U.S. into an economic powerhouse have begun to dissolve. Washington, D.C. reacts with legislation designed to prop up failing businesses—measures to keep them from competing with each other, or to force them to cooperate.

Dagny Taggart, VP of Operations for Taggart Transcontinental—the last great railroad linking the country—refuses to surrender to the cynicism and despair that poison everyone around her. She refuses to go along with the industrial cartel that her brother James pals around with. She refuses to drop out of society and laugh at the world’s misfortune, as her childhood lover Francisco d’Anconia does. Even as her corporation is saddled with regulations that guarantee her failure, and even as her best and brightest employees quit or vanish, she struggles on. Not because she wants to turn a profit—though she knows she’s entitled to one—or out of spite for her enemies—though she certainly loathes them. But because all she wants to do is create something worthwhile.

Dagny Taggart, VP of Operations for Taggart Transcontinental—the last great railroad linking the country—refuses to surrender to the cynicism and despair that poison everyone around her. She refuses to go along with the industrial cartel that her brother James pals around with. She refuses to drop out of society and laugh at the world’s misfortune, as her childhood lover Francisco d’Anconia does. Even as her corporation is saddled with regulations that guarantee her failure, and even as her best and brightest employees quit or vanish, she struggles on. Not because she wants to turn a profit—though she knows she’s entitled to one—or out of spite for her enemies—though she certainly loathes them. But because all she wants to do is create something worthwhile.

Throughout the first two-thirds of the novel, a recurring bit of popular slang sums up America’s cynicism: “Who is John Galt?” John Galt’s not a real person—he’s a mythical figure like Murphy or Kilroy. Asking “who is John Galt?” is the equivalent of saying, “why are you asking the impossible?” It’s a statement of resigned helplessness in a decaying world.

Dagny writes this slang off as a symptom of the world falling apart—until she suspects that John Galt might actually be real.

In the remains of one of the first companies to go under, she discovers the shattered remains of a motor driven by atmospheric electricity—a motor that would have brought cheap, abundant power to the entire world if it had been completed. She tracks down financiers, artists and engineers who have disappeared, and learns that in each case they had a visit from a mysterious man. This man talked with them for a few minutes and said something that made them leave the world behind.

Some of these creators vanish. Some of them go into blue-collar professions—driving trucks, or flipping burgers. But none of them return to their chosen work.

After an epic cross-country chase, Dagny finds a secluded mountain hideaway, protected by holographic illusions. The world’s greatest creative minds have retreated here, pursuing their masterpieces in private. They pay no income tax and perform no charity—they work for the joy of working and trade in mutual benefit to each other. And the entire gulch is powered by a motor driven by atmospheric electricity—the invention of one John Galt.

Galt tells Dagny what he told each of these fugitives: that society will never value the importance of creators so long as creators remain around to sustain society. It’s the output of rational people that allows the irrational to survive—and, at the same time, to question why the rational people should get all the acclaim. These inventors and artists didn’t walk away from their careers regretfully—they walked away joyfully, laying down the burden of supporting an ungrateful world.

They were the Atlases, supporting the world on their shoulders. When the time came, they shrugged it off.

Note: this is a woefully incomplete summary of the 1100-page epic that is Atlas Shrugged. I skipped over all of the subplots—such as the tension between Dagny and her brother James, Dagny’s affair with the industrialist Hank Rearden, Rearden’s deteriorating marriage, Dr. Stadler and his State Science Institute, Galt’s radio speech, Galt’s capture by the bureaucracy and the gang’s gung-ho rescue, etc, etc.

I also skipped over a lot of the substantial flaws in the novel. The rather melodramatic writing style, where every gesture is violent and every statement passionate. The substantial emotional repression which the protagonists inflict upon themselves. The odd epistemological ladder inherent to Rand’s philosophy, in which emotions necessarily reflect thoughts, which necessarily reflect value judgments, which necessarily reflect your worth as a human being. And finally there’s the moral quandary with which the novel ends, in which the supergenius protagonists leave the rest of the U.S. to starve while they hide in their mountain fortress.

It’s a superficial take. Bear with me.

I’m impressed that you read Atlas Shrugged, and jealous that you played Bioshock.

Hey, maybe they could make a videogame out of The Fountainhead! (Wait, does SimCity count?)

Ok, but I’ve got to know, is the philosophical aspect of Bioshock confined to the plot of the game, or is it also reflected in the gameplay?

I don’t own a console, so I’m a little out of the video gaming loop these days. But from what little I know, there seems to be a tension these days between the game-as-game and the game-as-plot, or perhaps the game-as-film, since it’s usually made up of cinematic cut scenes over which the player has little to no control.

From the reviews I’ve read, I get the feeling that there’s a choose-your-own-adventure aspect to the cut scenes, and also that choices during the shooter sections (do I kill this little girl for the powerups, or let her live?) can influence the plot. But this in itself doesn’t make the gameplay philosophical. There might be times when a player would do something strange from the gameplay perspective in order to further their enjoyment of the game-as-plot, but the levels would still be separate.

An analogy: The rules of Chess, like the theories of Ayn Rand, are fundamentally opposed to altruism. But when I was a little kid playing chess with my granfather, he would make “stupid” moves sometimes to avoid beating me too badly, or just to prolong the game. This doesn’t mean that chess-as-game has an altruistic element, it means that my grandfather was consciously deviating from his experience of chess-as-game in order to further his enjoyment of chess-as-social-ritual.

Flash forward a dozen years or so, to the wonderful/stupid computer game Battlechess. According to the rules of chess, your goal is to checkmate your opponent. If you can achieve mate quickly, there is no reason to take all of your opponents other pieces first (unless you feel like being a dick… another aspect of chess-as-social-ritual, although not one that my grandfather enjoyed). But you might well do it in Battlechess, in order to see all of the cute little combat animations that the programmers had worked so hard on. Again, this doesn’t change the way that chess works as a game: you’re deviating from those rules in order to enjoy something else.

So is Bioshock really a philosophical FPS? Or is it a normal FPS (in which the rules are: collect all the guns and use them to shoot everything), to which a philosophical series of cinematics has been attached?

Stokes: the central “choice” of BioShock is whether or not to harvest Little Sisters for their ADAM.

If you harvest a Little Sister, you kill her. You drain all the ADAM she’s carrying (note: never actually seen the animation for this). This gives you the maximum possible ADAM which that Sister carries.

If you free a Little Sister, you remove the ADAM-laden sea slug from her body and turn her into a normal, albeit weird, girl again. You get about half the ADAM you would normally gain. However, the girls’ matron, Dr. Tenenbaum*, leaves you “care packages” every time you rescue, rather than harvest, 3 girls. These care packages give you a bit more ADAM (though not as much as you’d gain by harvesting) and access to exclusive powers.

So – there is SOME philosophy in the gameplay. However, it’s not the most compelling choice (you pay a slight premium for being good, but not much). And I don’t know if you could frame it in terms of Rand’s philosophy. I suppose rescuers are self-made men and harvesters are parasites. Or maybe rescuers are altruists and harvesters are selfish. You could argue either way.

* Many folks comment on the fact that “Andrew Ryan” is an anagram for Ayn Rand. But it takes a real trivia nerd to recognize the connection between the thickly accented Dr. Tenenbaum and Alice Rosenbaum – Ayn Rand’s real name.

“Andrew Ryan” is an anagram for “Ayn Rand”? Says who?

Yeah. It is an anagram for “Nard Yawner” though.

Or “Ayn Randrew.”

Anagram minus a few letters. It’s slaves to tradition like you that drive good men under the ocean!

So from a purely amoral game-as-game point of view, it’s just a question of build optimization, right? You can choose to have a bit more of the in-game currency, or to have a few extra skills. This isn’t really a moral choice, although the game maps a moral choice onto it… How is killing the little sisters less moral than killing the pawns in chess? If it feels less moral, the game’s art director did a good job getting you to suspend your disbelief. (Which is kind of awesome in its own right.)

Having looked at the Bioshock wiki page, I can also tell you [spoilers] that the game has two endings, and that you have to avoid killing children to get the “good” one. There is something of a philosophical issue, but it’s utterly prosaic. At the end of the game (read: your life) you will end up in one of two places. For best results, avoid child-murder.

…

OR, for best results, play the slightly more difficult version of the game! I don’t know that the no-kill path is actually harder, but I can almost guarantee it, now that I know the payoff. Having a “good” ending reserved for beating the game on hard mode is a pretty standard feature, which may tell us something about what the morality of video games really is: a good old-fashioned Protestant work ethic. Kind of ironic, considering.

I would say that the actual major plot twist in the game (which I won’t spoil) points more to the gameplay aspect, and in a way part of the philosophy of Bioshock, than any “moral choice” the game imposes on you.

This isn’t really a moral choice, although the game maps a moral choice onto it… How is killing the little sisters less moral than killing the pawns in chess?

Fair enough, but can any “game” in the strictest definition of the word have truly moral choices in it? “You’ve just leveled up! Go confess a hated secret to your friend, and then press (A) to spend your experience points. We’ll wait.”

Before addressing anything else, I must say you’re made of awesome, John, for mentioning Rawls and the Veil of Ignorance! I squeeled with delight when I saw that. And “Perfect on paper can never be perfect in practice.”- yes, yes, yes! Heart you so much.

Now a question, since I’ve never read _Atlas Shrugged_: does anyone get faced with a situation where they must make a conscious choice between two moral paths during the course of the novel like they do in the game? If so, what direction (i.e. “good” or “bad”) do they go, and what happens to them by the end?

In terms of endings for the game, does choosing to harvest just once out of all opportunities mean you get the “bad” ending? Further, does choosing one way the first time set the game on auto for the rest of the time? Or, to put it another way, does the person playing get the option to harvest OR save every time a Little Sister is found? And if so, how many of each decision-type does it take to get the corresponding ending? See, I’m curious as to whether there are degrees of moral relativism involved and how successful they could be: if, say, you know you’re going to have a boss soon and oh, there’s a Little Sister, maybe I should take a hit off of her for the uber power boost- but later, it’s not as urgent, so you can (in terms of ADAM levels) “afford” to let that one go or something.

Gab – glad I could do it for ya.

The first question, re: Atlas Shrugged, would take a few hundred words for me to answer to my satisfaction. Short answer: one person does, they choose good, the bad guys kill them. Everyone else chooses good or evil as soon as the choice is presented clearly to them.

The second question, re: the game’s endings – and we’re now entering BIOSHOCK SPOILER TERRITORY, so be warned.

Every time you find a defenseless Little Sister, you choose whether to harvest or rescue her. So it’s a recurring choice.

If you choose to rescue each one, you get the “good” ending.

If you choose to harvest just one of them, you get the “bad” ending.

If you choose to harvest all of them, you get the “bad” ending with extra harsh language (literally – that’s all the difference Wikipedia ascribes to it).

@Jordan – I know what you’re getting at, and I feel like it’s something that might deserve its own post. People tend to overplay the degree to which a game offers you real significant choices. Good example is Grand Theft Auto. “It’s an open world!” people say. “You can do anything!” Except no, not really. If you want to beat the game, you have to do EXACTLY what the game tells you to. Sure, there are two endings, but I’m not sure that means much.

Of course, there are games that really do let you choose whether to play as a destructive killer, or an upright hero. For instance, in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, everything you did determined whether you became a good Jedi or a bad Jedi.

The thing is, I don’t hold the linearity against Bioshock. To beat the game, you have to traverse a certain path, killing certain bad guys as you do. This isn’t a morally ambiguous experience, but it can be very satisfying. And it’s even more satisfying when it’s mapped onto a morally ambiguous story, even if you’re not the one making the important decisions.

@Dan – I for one would love to see your spoileriffic analysis. If you really don’t want to put it in the public forum, send it to me at stokes at overthinkingit dot com.

@John – “Fair enough, but can any ‘game’ in the strictest definition of the word have truly moral choices in it?”

See, this to me is a really interesting question. You’re right, game systems don’t tend to require moral choice. But they do have a certain… well, value system might not be the best term, but it’ll do. Consider Mario 1 and Mario 2. In 1, you can only move forward, there’s a ticking clock, and most enemies can be easily killed for points. In 2, you can move in any direction, there’s no time or score, and for the most part you’re better off just avoiding the enemies. I don’t think it’s all that unreasonable to look for ideological differences there… but when people talk about how “deep” a game is, they’re usually talking about something else.

This doesn’t mean that people shouldn’t be making – or overthinking – games with complex, philosophical stories. But I think it’s always worth keeping an eye on how/if the philosophy is brought out in the gameplay.

I haven’t played, but from what I have read here thus far, it seems to me this particular game pushes a certain morality/philosophy. If harvesting one soul Little Sister is enough to take away the “good” ending, even if doing it more makes things worse, it still gives the fundamental lesson, “Killing kids is bad.” But the potential for picking and choosing makes fodder for an interesting psychological experiment. One could set up a control group with absolutely no knowledge of the game prior and have them play through it, and then have every other group gain a bit more information. If they know there is a “good” and “bad” ending, does that influence their decision? What about DEGREES of “bad”? And I’d really be interested to know if the train of thought of, “It’s just a game,” is changed for them when the potential victim is a Little Sister versus a thug or whatever else you must kill in the game.

(One small detail, though: do the Little Sisters do anything apart from shiver onscreen, or do they attack you when you find them?)

For some reason, I can’t get a fairly old Playstation game out of my head for this sort of experiment, the _Die Hard Trilogy_, because there are lots of ways to manipulate gameplay within the first and third movie’s games (hardly any for the second), but if you don’t do things within a certain set of parameters, you’re still screwed- and while some of the ways you can mess with things are, well, messed up, they are also quite easily interpreted as funny or ridiculous (running a civilian over and having a Samuel L. Jackson impersonator remark, “Are you aiming for those people?”, for example). Has anyone else played this game and would know what sort of things I mean?

(One small detail, though: do the Little Sisters do anything apart from shiver onscreen, or do they attack you when you find them?)

A Little Sister never shows up onscreen without a Big Daddy accompanying it. If you get within arm’s reach of a Little Sister, the Big Daddy will flip out and murder you swiftly.

If you keep your distance and observe, you’ll see (in what’s a neat little AI sequence) the Little Sister pad softly through the remains of Rapture. Whenever she finds a corpse, she plunges a giant hypodermic needle into it and withdraws its ADAM to stockpile. “Look, Mr. Bubbles,” she tells the Big Daddy. “It’s an aaaaangel …”

So whether you harvest her or not, you must kill the Big Daddy every time you see a Little Sister?

(And oh my goodness, “Big Daddy” with a “Little Sister” is wrong on so many levels…)

No, it’s entirely possible to bypass most of the Big Daddy/Little Sister combos. But it’s tough to beat the game without the expanded powers the ADAM gives you.

I think the moral choices in Bioshock extend a bit further than simply “killing Little Sisters gives you a bad ending (even killing just one) versus saving them all gives you a good ending.”

I think it’s in the REASONS for harvesting or saving the girls. It’s already been established in the above and well-written comments that you get more ADAM through harvesting Little Sisters.

Well, see, that right there means by killing even ONE of them, you are greedy, and that greed is what leads you to the bad ending, which I think would be good to spoil, but I’ll let someone else make that decision ;) Suffice it to say that your greed reflects you in the way Atlas’ and Ryan’s greeds affect them.

In all honesty, the more I think about it, I feel like the Big Daddys are the real victims here. Sure, the Little Sisters were kidnapped and implanted with a sea slug that causes them to go around pulling ADAM from every living thing, but at least Dr. Tenenbaum (and through her, your own character) wants to save the girls.

Nobody shows the Big Daddys mercy. You kill them out of greed, plain and simple; you can’t even get to the harvest/save decision with the Little Sisters until you whack each accompanying dude in the armored dive suits. Even if you use a power to get a Big Daddy on your side, his Little Sister will immediately escape through the nearest tiny ventilation pipe.

Plus Big Daddys have lots of cash and items that makes up for the ammo you need to put them down for the count.

What’s more, later on you have to dress like a Big Daddy, which takes cannibalism to a whole new level….

Wait- you EAT Big Daddys? Or is the cannibalism thing a reference to the searching of the corpse?

“A video game that makes you think” followed by a trailer for said video game, showing a city in the sea, that goes immediately into an implication of violence about to happen to a child before going into heavy violence and torture in front of the child. What/how exactly does that make us “think”?