Completely unrelated thought: is this title appropriate? It makes the movie sound like a romance, which it's so not.

At the end of Scent of a Woman, young Charlie Simms tells an obvious lie to the Headmaster of his boarding school, in front of all the students and teachers. He fully expects to be expelled. Instead, his new friend Colonel Frank Slade decides to get a few things off his chest. “If I were the man I were five years ago, I’d take a flamethrower to this place!” he thunders, moral outrage crackling out of his fingertips. (By the way, I always wondered whether he meant “five years ago, when I had more backbone and courage,” or “five years ago, when I could see what I was lighting on fire.”) When the dust settles after his five minute rant, the faculty board exonerates Charlie on the spot, the student body erupts into riotous applause, and (I assume) Headmaster Trask goes home to stick his head in a goddamn oven.

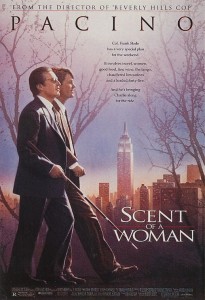

The speech probably has a lot to do with Pacino winning his only Oscar, and it’s a lot of fun. It’s so much fun, in fact, that it’s easy to miss two things:

- All this fuss is about a large balloon filled with white goo.

- It’s by no means clear that Charlie did the right thing.

Let me refresh your memory.

Coming home from the library late one night, Charlie and his friend Willis (Philip Seymour Hoffman) see three students planting something on a lamppost. The next day, after the Headmaster parks his swanky new Jaguar, a voice on the P.A. recites a satirical poem, and then a large balloon inflates over the car showing Trask kissing the ass of a gentlemen labeled “The Trustees.” When Trask pops the balloon, he and the car are coated in white stuff, and there is much rejoicing.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9H-ln9ZkxWY

Clearly the writer wanted to create the most elitist prank imaginable, working in both poetry and editorial cartooning. I’m pretty sure they got this prank out of Poor Richard’s Almanack.

Anyway, a teacher saw Charlie and Willis at the scene the night before, and Trask knows they know who did it. They both lie and claim they didn’t get a good look at the pranksters. Trask then says there’ll be a hearing after the weekend, and if they don’t name names, they will both be expelled. He then privately tells Charlie that he has a special arrangement with Harvard, and he can get Charlie in… if he cooperates.

Got it? Okay, let’s break it down.

The bribe, I feel, is an ethical red herring. That is, it SEEMS like it’s important to take into account, but it’s not. Think about it: if protecting your fellow students is the right thing to do, the bribe doesn’t make it wrong. And if being honest with Trask is the right thing to do, the bribe doesn’t make it wrong. The bribe gives us the impression that cooperating with the Headmaster is immoral. But really, the only immoral thing is naming names because you want the bribe. Colonel Slade actually says this in his speech:

I don’t know if Charlie’s silence here today is right or wrong; I’m not a judge or jury. But I can tell you this: he won’t sell anybody out to buy his future!

Slade leaves open the possibility that its okay to cooperate with the Headmaster, so long as you’re not doing it to get into Harvard. At least, that’s my interpretation. Later in the speech, Slade says, “He has chosen a path. It’s the right path.” Most people would interpret that as, “Charlie made the right decision in not snitching.” I actually think Slade just means, “Charlie made the right decision in not being tempted by the bribe.”

So let’s put the bribe on the back burner and examine Charlie’s predicament:

TRASK: Mr. Sims, you are a cover-up artist and a liar.

SLADE: But not a snitch!

Those are Charlie’s two choices: he’s either got to lie or snitch. Which of these sins is the lesser of two evils? Well, it depends on your value system, of course.

It’s actually somewhat ironic that Colonel Slade, a military man, praises Charlie’s decision to stay quiet. Slade is presumably a graduate of West Point, where the famous Honor Code says: “A cadet will not lie, cheat, or steal, or tolerate those who do.” In other words, if you know one of your fellow students has done something wrong, you have a duty to snitch. If you don’t, you’re just as guilty as they are.

They are deadly serious about the Honor Code at West Point. In 1951, a cadet named George Holbroke offered his roommate Brian Nolan help on a math exam. Nolan went straight to the administration. They then had Nolan infiltrate the cheating ring to see how many people were involved. That August, 90 cadets were expelled, thanks largely to Nolan’s snitching. Believe it or not, Nolan’s a hero to a lot of people.

But I’m guessing he’s not a hero to Busta Rhymes. In February 2006, one of Rhymes’ bodyguards was fatally shot on the set of a music video. Although there were many, many witnesses (over a hundred by some accounts), no one was willing to come forward. Absolutely no one. The NYPD Commissioner publicly complained about Busta’s refusal to answer any questions:

I’d think he’d be knocking on the door… If your employee’s murdered in front of you, you think you might want to talk to the police.

But in the hip hop world, any cooperation with the police for any reason constitutes snitching. Gangsta rappers, by definition, don’t want to be seen as law abiding citizens. Anderson Cooper once interviewed the rapper Cam’ron about snitching, and asked him if he’d call the police if he learned the man living next door was a serial killer. Cam’ron replied:

No, I wouldn’t call and tell anybody on him, but I would probably move. But I’m not going to call and be like, you know, the serial killer is in 4-E.

So a West Point cadet would say that Charlie has to tell the Dean everything. Cam’ron would say that Charlie should keep his mouth shut, even if he saw those three students raping a nun right there on the quad. Most of us, however, are neither cadet nor Cam’ron, but somewhere in the middle.

Let’s assume that people’s default setting is to cooperate with authority. (This is, after all, the very backbone of the Social Contract, without which life would be nasty, brutish, short, and generally sucky.) I see two general circumstances in which one might ethically lie to an authority figure.

1. You think the offense is small and victimless. In my books, ethics doesn’t force you to report your neighbor for not recycling, or your friend for illegally downloading mp3’s. Overlooking these minor infractions is justifiable because strengthening neighborhood and community bonds is a worthy end. A society of tattletales and spies wouldn’t be a very pleasant place to live. Therefore, a certain amount of “mind your own business” is fine.

2. You think the justice system is unjust. Take, for example, the McCarthy Hearings. In general, we can agree that cooperating with Congress is a good thing. But looking back on the McCarthy from the vantage point of 2009, refusing to name names was the only right decision. The people who cooperated, like Elia Kazan, have been judged harshly by history. And yet, all they did was honestly answer a question, while under oath, posed to them by a United States Senator.

Another good example is the concept of jury nullification. This is the rare instance in which a jury refuses to convict because the jury dislikes the law in question. At first, this may seem like an abuse of the jury system – how can it be ethical not to uphold the law? But jury nullification is actually a crucial part of our legal system. John Jay, our first Chief Justice, wrote, “The jury has the right to judge both the law as well as the fact in controversy.” Today the concept is controversial, but definitely alive and kicking. In Indiana and Maryland, judges are actually required to explain to juries they have the right to nullify.

Okay, back to Charlie. I think he decides not to name names for both the above reasons:

1. It’s a prank we’re talking about here. The only harm that was done was done to Trask’s pride, his suit, and his car. The crime isn’t severe enough to overcome Charlie’s natural inclination to be a good friend (even though the perpetrators aren’t really his friends).

Moreover, it’s a prank Charlie approves of. Trask is unpopular, vain, and generally assholish. When he gets his comeuppance, Charlie laughs along with everyone else. By refusing to cooperate in the investigation, he’s practicing civil disobedience. He’s standing behind what the pranksters were trying to accomplish.

2. Maybe the bribe plays a role in this ethical calculus after all. Because of the bribe, Charlie knows for a fact that Trask isn’t a fair administrator of justice. He knows the system is broken. And since he knows this, Charlie can’t in good conscious do anything to help that system.

There’s actually a shortcut for solving this moral dilemma: Utilitarianism. Just look at the outcomes and pick the one that’s the least bad for humanity in general. If Charlie stays quiet, he will likely be expelled. If he names the three pranksters, they will likely be expelled. Three is bigger than one, so a Utilitarian would say Charlie should keep quiet for the greater good. (I don’t believe that’s how Charlie made his decision. I’m just throwing it out there.)

But Charlie’s decision may not have been made for ethical reasons at all. The entire student body is sitting there, staring at the back of his head; the peer pressure to stay silent is enormous. Charlie’s an outsider, and he will certainly lose the few friends he has if he rats out the pranksters. Sure, Trask has threatened to have him expelled if he doesn’t. But honestly, I think a lot of people would rather be expelled a hero than stick around a villain (especially teens).

Slade praises Charlie’s actions as the hard choice. I’m not so sure – usually you don’t get a standing ovation for making the hard choices in life. That’s what makes them hard choices. But I do know that Brian Nolan, the cadet who helped get 90 of his friends expelled… THAT kid made a hard choice. Maybe he was a classmate of Colonel Slade’s.