USA! USA! USA!

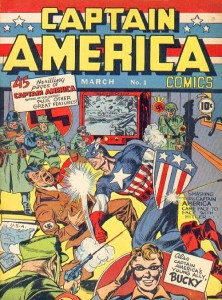

The basic Captain America story isn’t supposed to be complicated. Steve Rogers is a nice kid from Brooklyn with a heart of gold and unfailing sense of duty who turns into a Super Soldier and fights ze eehvil Ghermahns during World War II, the Least Morally Ambiguous War ever. Along the way he loses friends and gets the girl, but stays true to his patriotic duty to his country.

Future iterations of Captain America would struggle mightily with morally ambiguous situations and the symbolic burden of being the mascot of a nation-state whose actions he doesn’t approve of, but none of that is even hinted at in Captain America: The First Avenger. Most of this is due to its setting in World War II and that it’s an origin story focused on the creation of a hero. But even with those two factors as a given, the movie takes great care to steer clear of anything even remotely controversial. Even the gravitas of Nazi evil is mostly pushed aside by the fictional HYDRA, a rogue Nazi science unit that breaks off from the Third Reich and even targets it as one of its enemies. Rogers recruits African- and Asian-American members for his team, but the racial prejudices that both men would have surely endured are never mentioned in the movie.

USA! USA! USA!

From a story telling perspective, the movie made the safe choice by not bringing in these more complicated, challenging elements. The movie stays lean and focused on Rogers’s transformation and heroics, and everything else is in support of that. It make sense to show Rogers’s guilt over his friend Bucky Barnes’s death, but it probably wouldn’t make sense to see Rogers have an argument with Gabe Jones, the African-American member of the team, over segregation back home and abroad. It’s not essential to the story.

I recognize all of that, and yet, I can’t help but be a little disappointed that Rogers doesn’t have to struggle with anything beyond personal loss and HYDRA-thwacking in this movie. It’s justified for all of the reasons I cited above, but I can’t help but yearn for these things. This is OverthinkingIt.com, after all, and it’s not exactly in our nature to let any movie off the hook, especially when the movie’s hero is presented as the physical embodiment of a complicated nation-state, and as such demands the same level of scrutiny and debate we give to that most complicated of nation-states, America.

So with that in mind, let’s engage in a thought experiment: how could a different Captain America movie put our Star Spangled hero into some more thought-provoking situations?

Captain America as a Holocaust Movie?

What Would Captain America Do?

Rogers arrives in Italy in November 1943. This may or may not have been intentional on the part of the filmmakers, but either way, the choice of time and place give Rogers plenty of distance, both spatially and temporally, between the horrific scenes discovered by US troops as they liberated concentration camps in Germany in the spring of 1945.

But what if the timing were different? Putting the HYDRA threat aside for a moment, what if the U.S. government saved Rogers for the D-Day invasion and the final push into Germany? What if Rogers had come face to face with Nazi mass murder and all of its implications?

The testimonials of American GIs who liberated the camps are well-document. They reveal a range of strong emotions: shock, horror, trauma, and even guilt that they somehow weren’t able to do more to stop these atrocities from happening.

Now, remember that the doctor who invented the Super Serum implied that the formula affects the mind as well as the body. What was bad be comes worse, what was good becomes better. Schmidt’s bad personality traits amplify and turn him into a super-villain. Rogers’s good personality traits amplify and turn him into a super-hero.

What Would Magneto Do?

Given these augmentations, Rogers would have had an intense reaction to the concentration camps. Perhaps he would have been paralyzed by the evidence of man’s seemingly limitless capacity for cruelty and collapsed into despair. Perhaps he would have been filled with guilt over his inability to stop the killings and question the extent to which his country did enough to stop them. Or perhaps he would have been filled with righteous anger and devoted his life to bringing every last Nazi to justice. (It wouldn’t be totally out of character for a Marvel character to become a Nazi hunter, after all.)

Few people would want to see Captain America curled up in a fetal position, crippled by PTSD, or Captain America as a cold-blooded Nazi hunter, but I think many would share my interest in wanting to know how this idealized symbol of righteous American power would have reacted to this most extreme situation. Presumably with great sadness, possibly with some disillusionment as well, but also great compassion for those that suffered, not to mention an even stronger resolve to keep fighting and preventing such evil from happening again.

Captain America as Struggle for Racial Equality?

Gabe Jones, Black Guy

The above Holocaust scenario is pretty far removed from the movie that came out this past weekend, but the subject of race isn’t far from it at all; it’s on screen for anyone to see, although it’s never explicitly discussed in the movie.

As I mentioned earlier, there are two racial minorities in Rogers’s core team: Gabe Jones, an African-American who learned both French and German at Howard, a prestigious black college, and Jim Morita, a Japanese-American from “Fresno,” which he points out to Rogers after he mistakes him for a Bad Guy Japanese. Both would have been the subject of harsh discrimination during the World War II era. African-American soldiers were typically prohibited from combat and mostly relegated to service roles. Segregation of America’s armed forces didn’t end until 1948, and persisted unofficially through the end of the Korean War in 1953. Japanese-Americans were, of course, infamously interred into camps in the United States. Japanese-American men not in the military were given 4C draft status–“enemy alien”–and all those that were in active duty were discharged shortly after the Pearl Harbor attacks. Both African- and Japanese-Americans would eventually create specialized fighting units that served with distinction during the war (the Tuskeegee Airmen and the 442nd Infantry Regiment, respectively), but those were the exceptions, not the rule.

Jim Morita, Asian Guy

All of this would not have been lost on a “kid from Brooklyn” (especially one that paid close attention to the newsreels before movies, as was depicted in the movie). Suspicion of Japanese-Americans was rampant after Pearl Harbor, and the internments made national headlines. Closer to home, New York City’s history before and during the World War II era is pockmarked with numerable moments of significant racial tension, from the draft riots of 1863 to the Harlem Bus Boycotts of 1941.

Jones and Morita were not strangers to Rogers. The movie alludes to a strong sense of camaraderie among the men, and given the awesomeness of their action montage, it seems that they’d been through a lot together. Surely the subject of racial discrimination would have come up among the men, especially with Morita, who, being from California, very likely had family living in internment camps at the time.

My interest in wanting to see how Rogers would have reacted to these conversations goes beyond a simple wish that any given commercial movie be more sensitive to topics of race and prejudice. It’s more directly tied to my desire that Steve Rogers be forced to confront these issues. Not in spite of the fact that he’s Captain America, but precisely because he’s Captain America.

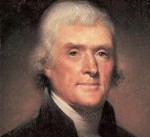

Thomas Jefferson: white guy, slave owner, the original Captain America?

Many have argued–myself included–that the one common thread running through the long, sprawling, complicated American narrative is the tension between the loftiness of its egalitarian ideals and the constant internal struggle to turn those ideals into practice. The same man who wrote “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” into the Declaration of Independence also owned hundreds of slaves on his Virginia plantation. Over 200,000 Union and Confederate soldiers died in a war fought over slavery, a war whose legacy was still unresolved at the time of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s and in many ways remains unresolved today, in the 2010’s.

Oh, and we fought a war against a genocidal racist maniac while our own army was racially segregated.

In other words, the struggle for racial equality isn’t the seedy underbelly of American identity. It practically defines it. And this is why I see the lack of any acknowledgement of racial tension in the Captain America movie as a real lost opportunity. As our idealized symbol of righteous American power, Captain America should obviously embody all of the great things about the American spirit, but he shouldn’t pretend that the terrible things about the American spirit don’t exist or ignore their destructive power. In fact, if he’s the Great American Hero we so desperately want him to be, then he should be confronting these issues head on.

Asking for a Captain America movie in which our hero saves the Jews is probably too much to ask for. So would a Captain America movie in which Rogers leads a Civil Rights movement at the same time he’s battling Nazis/HYDRA in Europe. But I don’t think it’s too much to ask for a Captain America movie in which Rogers has to confront American racism, at least a tiny little bit, among his close-knit, multi-cultural squad.

But It’s Just a Summer Action Movie

Those that say I am in fact asking too much of this movie, that it shouldn’t really be criticized for skirting the issues of the Holocaust and racial prejudice, wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. Captain America, in spite of its historic setting, is ultimately a fantasy movie, not a gritty realistic portrayal of hardship during World War II. It has no “obligation” to tell a more complicated, thought provoking story. You could even say that X-Men: First Class, with its moral dilemmas and civil rights allegories, more than adequately plays that role for this summer’s slate of superhero movies.

None of these things are necessarily wrong. And I remind you of what I said at the beginning, that the movie “made the safe choice” to not include things like the Holocaust and racial prejudice in its story, and that at least partly because of that, the movie succeeds in providing solid entertainment.

But let me close with this thought: were the signers of the Declaration of Independence (yes, those same slave-holding white guys) making the “safe choice” when they signed their names to a document that essentially marked them as traitors to the British crown? No. America was created by those who made the unsafe choices, those who took risks, those who challenged the status quo.

Shouldn’t Captain America do the same?

During crowd shots of soldiers, there were a few black faces. That means that in this world, the army was desegregated already. Yes, the Japanese probably still faced some discrimination due to Pearl Harbour, but maybe in the Marvel Movie Universe, they overcame segregation much earlier?

I’d like to think that Thor gave Nick Fury some Asgardian technology that allowed him to go back in time and jumpstart the Civil Rights Movement a few decades early. I’m pretty sure that Nick Fury: Time-Traveling Activist would probably be the best movie ever.

Kinda remind me one comic has (What if#28 and #29 volume #1) that make a non-continuity story that tell what Happen if Captain America hadn’t been the only super soldier, he end up saving Magneto from the concentration camp and give him a stiring speech that giving him a more concilatory outlook in the mutant/human conflict and he create the X-men

Mind you, later Captain America get his identity stolen by the Red Skull, run for president and transform the U.S into a fascist dictatorship and later kill the x-men except for Magneto who promtly declare War on humanity

I was really hoping they’d find some way to comment or reflect on the over-the-top propaganda that audiences and Capt. America were drinking in throughout the movie. They could have made some aspects WW2 at least a little morally ambiguous. It wasn’t nearly as rosy as they painted it and movie feels like it succumbs to becoming the propaganda it displays.

Aha, all is explained: the propaganda posters come from an alternative universe, the one in which Captain America exists.

I think the filmmakers assume many people are coming in already so cynical and disillusioned with America that they can’t even get enough care and energy to confront tough issues so Captain America needs to pump them up by being all pump. But what would have pumped me up was knowing America can face those tough issues.

The movie sets up the dynamic of emotional experience equals responsible use of power. Roger’s knows what it’s like to have a weak body so respects weakness when he is strong.

To pretend America has always been pumped up with Vita-Rays from day one and never had a moment of political weakness would mean America has no appreciation for political weakness because it never experienced it.

As said in the podcast Rogers is weak, has a martyr complex, and doesn’t back down from a fight he can’t win, which are not traits you want in a super soldier. You could make the claim that Rogers gets his strength from denial of reality, but that cynical reading would have been lessened had Rogers fully confronted a weakness America denies, that would have really been proof of a more socially relevant strength and thus more inspiring. And I see no reason why it couldn’t be just as entertaining, Team America: World Police did it, with puppets no less.

But what would have pumped me up was knowing America can face those tough issues.

+1

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

– Abraham Lincoln

While slavery was one of the causes of the war, please don’t oversimplify by saying that the war was fought over slavery. This is Overthinking It, after all. And really, America only went to war against “genocidal racist maniac” because he was threatening the rest of Europe, not because he was genocidal or because he was racist.

At the risk of opening up a big ‘ol can of worms…

“While slavery was one of the causes of the war, please don’t oversimplify by saying that the war was fought over slavery.”

The quote by Lincoln is accurate, but I don’t think it necessarily disproves or is mutually exclusive to the idea that the Civil war was fought over slavery.

The Southern states overwhelmingly cited the threat to slavery as their primary reason for seceding from the union. I point readers to this article in the NY Times that cites statistical language analysis to this effect:

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/28/the-causes-of-the-civil-war-2-0/#more-90835

But it does acknowledge that Northern reasons for fighting the war weren’t about slavery on the surface:

As for the second point:

“And really, America only went to war against “genocidal racist maniac” because he was threatening the rest of Europe, not because he was genocidal or because he was racist.”

Yes, this is true, but I don’t think it weakens the point that I’m trying to make, which is that, in spite of America’s obviously moral superiority to the Nazis during WWII, it still shared in some of its enemy’s evils with regards to race and the dehumanization of fellow human beings. I thought this would be an interesting thing for Captain America to grapple with.

While I wouldn’t deny that there was a “language of slavery,” I think the issue wasn’t slavery in itself, but the economic impact on the South that abolition would bring. The article points out how protecting slavory is a means to an end- for economic freedom, keeping back black uprisings, etc. And it discusses how slavery was couched within a multitude of other issues.

Also, that article focuses on Virginia- and, as it points out, Virginia took a long time to decide what to do. It was ambiguous for a while, and was by no means the harbinger of the secession.

“The North did not fight at first to end slavery, but the South did fight to protect slavery.” Yes, but the information in article itself makes this statement feel too minimalistic- there needs to be more at the end. “…to protect slavery because of how slavery was so integral to myriad institutions and practices in the South.” Or something. Saying it’s slavery *period* still isn’t going deep enough.

And a bit of disclosure: I’m not a big fan of quantitative analysis like this- tallying the number of times a word gets used doesn’t tell you why it’s being used, or when, or where. So I could also just be biased and want to nitpick and disagree with it.

So just to be clear, I don’t think slavery wasn’t an issue- I just think there was a lot more going on, and it was one of many- and was connected to many, too.

Would “deeper” be “to preserve a system of racial preference”?

This is the reason poor, even landless whites fought to the death to defend the slave state, from the time of the onset of the colonial British “divide and conquer” strategy vis a vis European and African indentured servants–no?

Am now excited to watch Captain America, what with all that possible overthinking ^^

*start disclosure* The next few sentences are based on my understanding of 1776 onwards from the book “John Adams” by David McCullough, and besides a general understanding of the American Revolution, I have no other points of reference. *end disclosure*

Were the Founding Fathers defined by their slave ownership? It seems that while the two Virginian presidents (Washington and Jefferson) owned slaves, Adams did not, and was opposed to it. And if the Congress that assembled the Declaration was in fact equally divided among the 13 states, I would assume that the North and South were equally divided, and therefore would be divided in the slave ownership issue. Would it be fair, then, to paint an entire generation by what half its members did?

*end American history reference*

That being said, Captain America could have been better portrayed had it addressed the issues of the day. An entire generation would have been introduced to relevant issues of racial segregation and the conflict between “the Nazis are evil” and “the Nazis were fighting for their leader, too.” It really was a wasted opportunity.

Oh well, when the time comes and I get to watch it on the big screen, I’ll just enjoy it for what the director and screenwriters left it as: another summer blockbuster. I’ll do my overthinking somewhere else.

One more thing: that shot of Captain America during the Holocaust (captain-america-concentration-camp) reminded me of an art exhibit I saw when I recently went to Singapore. It was entitled Superhistory, by Agan Harahap of Indonesia, and it features superheroes and other movie characters (it even had The Joker!) in famous historical shots. Too bad the exhibit is already finished, though.

http://www.mopasia.com.sg/exhibition-superhistory.shtml

That led me to a thought that would tie in nicely with this article: the fact that the superheroes fit so perfectly in these historical shots only signified that fictional characters, if they are to function most effectively as a mirror of society, should not be removed from the issues of their era, and that new characters should be made for the new generation.

So how would Capt. America grapple with these thorny issues? The two ways I see it being done in a movie are A. He rewrites history and we vicariously feel that victory to come to terms, or B. He fails to stop history happening in the shameful way it did and we go with him through his tragic journey of guilt.

With something like the internment, it felt like it made sense to lots of people at the time, which is the real danger, I imagine the scene would play as Captain America agreeing with it at first then finally realizing how hypocritical it is then stopping it, in a Huck Finn way where he knows it’s against what society says and feels conflicted that he feels it’s right to free them on a humane level. The tragic guilt way may be too heavy for Capt. America, and the first maybe denial but it is how the rest of the movie operates, I mean it’s denying there was segregation but it’s still a progressive take on race, so I don’t see why it couldn’t be done on something larger like the Japanese internment and still be an entertaining adventure movie.

On counterpoint, Stanley Kubrick said in an interview he didn’t like Schindler’s List because he felt the holocaust was about the failure to stop the death of millions, not the success of saving a few. I guess he feels the danger is people get a false sense of closure, that it vents the outrage needed to stop something like that?

I don’t think Captain America by being an adventure movie runs the risk of accidentally solving racism though.

Can’t we have an option C? He leads the lesser of two racist systems (mid-20th century western democracy, not fascism) to victory not necessarily “solving” racism but certainly disenfranchising state-wide implementation of the more trigger-happy variant of it. Can we have a (struggle for) net reduction of racism even in there’s continual problems?

Damning with faint praise, there.

America was the first country in the history of the human race where the slave OWNING class went to war to end slavery!

With one of the primary motivations being to reduce incentives for the “propagation” of the enslaved? The 19th century Abolitionists weren’t exactly as “modern” as we’d like to think sometimes. Sometimes faint praise is pretty much earned.

Besides, even if us white Americans were such great people with regards to racially-systematized slavery, we were pretty happy (in the North, South, and West) to have racially-systematized pseudo-slavery on a large scale until the Civil Rights movement and arguably is still pretty intact today (Latino migrant workers anyone?).

I doubt this was your intention, but your remarks are so general as to smack of Southern apologetics. ‘Tis much safer to be a slave in the South than a factory worker in the North, and all that rot.

Also, who said all the abolitionists were white?

Young Admirer: Hey Cap’n! Is it really morally okay to punish the Germans for being racist and evil while America is just as guilty of racism and evil?

Captain America: Not now, junior, I’m being shot at by Nazis. Maybe we can talk about this after the war.

“Just as guilty?” Scuse me, but CONCENTRATION CAMPS?

Yeah, that’s a touch out of proportion, but it’s not like the US got damn close too. Japanese Internment, the Bracero Program, and various Native American extermination/indoctrination/resettlement campaigns, anyone?

Hell, where do you think Hitler and Ratzel got the idea of Lebensraum from? Hint: What industrialized country in the world had a frontier at that point?

The Trail of Tears (thank Calhoun and Jackson), which was a death march, inspired Ataturk, who marched Armenians do their death in the Armenian genocide. Hitler looked to Ataturk as his hero and a model for what he wanted to do in the German-speaking world.

Also, if you look into the history of smallpox and Native Americans you will lose your lunch VERY quickly. In some cases Christian missionaries actually spread pox-infected blankets or, after the vaccine became available, denied vaccinators passage to Native American communities. SICK.

I don’t see a great deal of difference between the genocide of Native American tribes by American citizens and the genocide of Jews and Gypsies by the Nazis, sorry. Btw, look up “Einsatzgruppen.” Okay, now google “Mountain Meadows Massacre.” And while the MMM was an isolated event (carried out by a ‘rogue state’), there were multiple campaigns sanctioned and carried out by the US armed forces to kill Native Americans and deprive them of their property.

http://www.nerve.com/entertainment/the-five-most-leftist-things-captain-america-has-ever-done

– Just to continue the thinking on Captain America (comics)

This may not be over-thinking it, but I was not as pleased with the movie as I had hoped. I really like the struggles of Steve the scrawny kid. I liked that he was content to wait for the right woman. I loved the moment that he jumped on the grenade.

I felt like, after he got super-sized and to the front, he lost that feeling of “striving.” Even losing his friend didn’t resonate all that strongly to me, because what he’d wanted before was to be on the front lines, and while I don’t want to belittle the effect such a loss would have, it wasn’t really part of the theme of “just because you have strength doesn’t mean you should use it” that seemed to be implied in pre-Captained portion. He got his dream, and it was pretty much everything he wanted, except he did lose a friend, but then he got over it. He had an objective, but not something he was striving for.

Perhaps, if there wasn’t the need to shoe-horn him into the Avengers, the story would have taken a different arc with a more satisfactory ending, perhaps where he realizes, as this article suggests, that what he’s fighting for isn’t perfect, but sometimes it’s still worth the fight.

As an Italian, I must object that, being in Italy in november 1943, Captain America didn’t see the horror of war. Of course the liberation of the concentration camps was probably the worst part of WWII but in the same time Italy was living one of the worse time too. In late September there was the creation of the “Repubblica di Salò” and the outright occupation of northern Italy by the Nazis. The Italian Resistance (la Resistenza)was in his early step and to stop it there were many massacres in retortion of their actions.

Cap had plenty of opportunity to see the horror of war.

The closest Cap gets to seeing the “horrors of war” is when he’s complaining to Agent Carter that he’s sitting on the sidelines while everyone else is fighting and dying. Cut to a bloody and bandaged guy on a stretcher.

This brings us back to this idea of what, if any, “obligations” a movie has in terms of accurately portraying history and/or bringing up difficult subjects, especially when the movie is set in WWII.

I do knock the movie for doing neither of these things, but I’m not quite ready to carry my criticisms to the logical extreme, which is that every WWII movie needs to have “Saving Private Ryan” levels of gore and/or “Schindler’s List” levels of Holocaust horror.

One could argue that movies like “Captain America” are a net negative on society’s understanding of history and the lessons to be drawn on it. I’d say that by themselves they’re neither positive nor negative unless there are outright myths/distortions/falsehoods presented as historical fact.

Yes, it’s a shame that people don’t know their WWII history as well as they should, both at the macro level as well as the micro level, but for that, we have much greater forces to blame, like weak history curriculum in schools and people’s general lack of appetite to hear about unpleasant things.

Dude, he was all over the place. He saw men gunned down right next to him all throughout the movie, and was shown drinking to the memory of his best friend in the middle of a bombed out city. And his primary mission was storming NAZI LABS. That’s enough “horrors of war” for one day.

They didn’t focus on racism issues or the holocaust or the bigger perspective of world war II in the movie because

1)People are sick of whiny bitches who try to sound “thoughtful” by endlessly dragging the corpses of sins past out of their shallow graves. Yes, America has done wrong things in the past, thank you for reminding us YET AGAIN, Poindexter. Mind if the rest of us, who actually LIKE our country, stop and remember the things we got RIGHT? And maybe along the way we’ll take a moment to recall that while we HAD those problems, we are also the ones that FIXED them…. precisely because of the principles which Captain America was supposed to represent. Liberty, Justice, human freedom. America inherited the institutions of slavery and racism from the Old World, but it was those principles unique to America’s foundations that brought about their end as institutionalized entities– that made it even feasible to question them in the first place. Captain America was about the virtues that make America great IN SPITE OF the warts and scars and blemishes she carries. Just like Steve Rogers, we don’t like bullies. We’ll sacrifice ourselves to protect what we value. And we’ll go down fighting if we have to.

2)It would be stupid to use Captain America, a one-off, strategic secret weapon, in the broad front of the War. You don’t send a navy SEAL to do the work of an army grunt….you send him to take out the most tactically and strategically important targets you can find and he can reach. Throwing him on the beaches at Normandy would (internally) be a stupid waste of a VERY limited resource, and (externally) be something of an insult to the real heroes who actually DID storm the beaches at Normandy— and did it without the benefit of a super-serum treatment or a bulletproof shield.

If the mistakes and outright horrors of the past are forgotten en masse by blinded patriots, in favour of remembering and lauding only those so-called rectifications, absolutions, and great ‘fixes’; then it becomes a job worth undertaking to ensure these mistakes are not forgotten! The people who ignore history, or rather pick and choose the bits they like, are doomed to repeat it’s failures and miseries.

“We’ll sacrifice ourselves to protect what we value. And we’ll go down fighting if we have to.”

The dark irony here has already been pointed out, and while I stress that I in no way intend to equate American segregation and racial inequality with the Nazi orchestrated Holocaust – the scale of the latter being unprecedented – it is a hypocrisy, one that is definite and unyielding. At the time of the second world war there still existed no legislation against lynching, the shadow of Jim Crow, and many other inequalities including the racial segregation of the armed forces. World wide media attention upon the racial situation in the United States in the wake of WW2, as well as the birth of an invigorated and orchestrated Civil Rights campaign, kickstarted American response at the federal level – the country could hardly allow such a useful weapon for communist propaganda to exist unfettered!

To state so glibly that ‘America inherited the institutions of slavery from the Old World’ is, ironically when one considers the overarching intention of this particular website, a vast oversimplification. A statement of fact it may be, but it tends towards a childish we-didn’t-start-it defence, or to quote Billy Joel, ‘We didn’t start the fire.’ Perhaps not, but some 200 years of fanning the flames hardly renders a nation guitless.

‘Those principles unique to America’s foundations that brought about their end as institutionalized entities’. The principles of Enlightenment philosopher John Locke and Classical Liberalism hardly count as ‘unique to America’, a nation cannot claim copyright on philosophical ideas, whether it can claim a constitution famously based upon them or not.

Furthermore, the oft exulted Emancipation Proclamation only freed slaves in those confederate states that did not rejoin the union. While it led directly to the abolition of slavery by the ratification of the 13th Amendment after the defeat of the confederates in 1865, it was, in reality a war tactic, used by Lincoln to destabilise southern slave communties and provide union soldiers with a honourable cause to fight for, so as to blind them to the fact they were fighting countrymen. Not only is the Emancipation Proclamation not the great slave freeing edict it is masqueraded as, it is hardly as though Lincoln’s proclamation was the first legislation of it’s kind around the world. The origin of legislation denouncing slavery as illegal and immoral is the United Kingdom – having been abolished in the British Empire in 1807 -, hell most Latin American countries abolished slavery some 50 years before the USA – though it is true that in those countries it still went on to some degree up until the 1870’s. All this having been longwindedly stated, how on earth is there any semblance of truth in claiming that it was, ‘principles unique to America that brought about there end as institutionalised entities’?

It is all well and good to be proud of one’s national affiliation and thus proud also of said countries percieved achievements, however, to assert that the realist, that refuses to concurr that said achievements render the mistakes inconsequential, does not ‘like’ their country is just ridiculous.

Relevant reading: NY Times columnist Charles Blow weighs in on “Captain America” and its “racial revisionism.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/30/opinion/blow-my-very-own-captain-america.html?ref=charlesmblow

From the article:

AMen.

I am of the opinion that it wasn’t until World War II forced us to confront racial discrimination at its worst that American society began to really become aware of the problem. So having Captain America confront it, and take a stand on it, probably would be as anachronistic as a racially integrated combat team. It should be kept in mind that while America wasn’t one big happy integrated family, neither was the entire country as bad as Mississippi or Alabama. Steve Rogers, the “kid from Brooklyn” was probably ambivalent on the whole matter. He would have had to have grown up amongst people of different races and cultures, so having an African-American and a Japanese-American on his team wouldn’t have been that big a deal to him.

One conceivable subplot has him become aware of the extent of racial discrimination in the U.S. as Rogers became “Captain America” the superhero. It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to toss a few real incidents into the script. Like the time when Lena Horne was perfoming for the USO at Fort Riley KS, and was horrified to find German POWs in the front rows while black soldiers were segregated in the back. She promptly came down off the stage and walked to the rear to perform directly for them. She subsequently refused to perform for segregated troops.

There were many other incidents on the Home Front where black troops were refused service at segregated facilities while German POWs were allowed in. There was even a riot at Fort Lawton near Seattle over such discrimination.

But concentrating on those issues would have made for an entirely different movie. One that’s been done before, in “Hart’s War”.

Better to show just a bit of the problem, and use it in Roger’s character development. I think it would be more satisfying to take the costumed hero that America thought it wanted and let him become the real hero that America needed.

It would have made sense to show the naive kid from Brooklyn seeing incidents of racial discrimination and ugliness that “don’t seem right” to him, even though he’s not in a position of power or really has the self-confident or awareness to challenge them at the time. It would inform the character he became. That would be both subtle and good storytelling and make comix fans like me happy.

Instead they just sort of gloss over racial issues entirely. Lame.

Well, there were reason to choose the “safe choice” for the film, that go beyond just creating a lean story. Remember that this film is called “The First Avenger” to overseas markets. They intentionally decided to downplay the America aspect of the movie. It would take a very, very skilled director to make a film that would do reasonably well both here and abroad, while also saying something meaningful about the Holocaust and racism.

In addition, there’s a lot of baggage in WW2 in other countries in comparison to the US. There’s the general criticism of how countries like Russia and China have made great sacrifices in human lives, but are under represented in comparison to the achievements of the US, or the use of nuclear weapons to end the War, or the fact that human experimentation was done in WW2 by Joseph Mengele and Unit 731.

Somehow I doubt the overseas numbers are going to be anything but crap. Some fantasy properties do well overseas, but even the ones that do well don’t measure up to properties like James Bond in worldwide numbers.

Also, how would US vs. Nazis play into US Russia and China baggage? American doughboys fought on the side of the White Russians after WWI, but the US and USSR were allies by the time the US entered the European conflict. The US also backed the Nationalists in China both before and after WWII, but the Communists and Nationalists formed a truce during the Japanese invasion and the US was instrumental in putting Imperial Japan down.

Japan is usually a reliable audience for US fantasy crap so I could see being sensitive about the treatment of Japan… but it’s not like they don’t know that their Axis ally lost the war (ever seen Hetalia?). If Steve Rogers and Fresno Guy had gotten in each others faces and then agreed to be friends, it would have been more realistic, less contemptuous of the American audience, and would not have challenged contemporary Japanese narratives (note I do not use the word “history”) about US-Japanese relations.

Talking about Nazis wouldn’t offend Germans because Germans acknowledge that Nazis are bad… unless you’re a disaffected unemployed punk, in which case you aren’t buying movie tickets anyway. Same goes for Eastern European Nazi sympathizers. Is Lithuania considered a key overseas market for a piece of Americanocentric dreck?

If the next Avengers movie is supposed to be the real world sales ticket, and this is just an origin story, why would the sales of that movie by contingent on the first? Not seeing it. I don’t think you need to go into deep explanations of the origins of a character called “Captain America”. Super-soldier serum, shield. Done.

Giant missed opportunity to entertain North American/British audience and make them think at the same time.

Certainly, the one I feel worst about when I’m having my post-colonial guilt sessions (thrice a week!) is the firebombing of Dresden. Actively targeting and killing tens if not hundreds of thousands of people.

Here’s what Jack Kirby, who co-created Captain America and revived him in the 1960s, had to say about his OWN experience as an infantry Scout in WWII, including his discovery of a concentration camp:

“At that time, the common man felt downtrodden; it was the same for Americans, we were feeling the same pressures back then, but we had Roosevelt and they had Hitler. It almost happened here; Hughie Long tried the same approach as Hitler. He wanted to take things over and run things for himself. Guys were unemployed and would listen to anybody. They thought he had a better idea; that he could fix the situation. I forget where he came from, but he was always making a big deal about everything. Somebody finally got fed up with him and had him shot. Hitler was immune to this because he was the one doing the shooting.

I was not prepared for the military experience personally; most of what I knew about the world came from the papers, books and movies—mainly movies. Like everybody else I was fed stereotypes by the movies, by writers who were pulling down big dough for writing that stuff; they didn’t realize that it was a kind of a beginning of an education for most of the country. There were very limited communications: A telephone was very hard to come by, not like today. To own an automobile you had to be semi-rich, and nobody ever took a cab; those were taken by rich people too. And airplanes? We all took trains back then and you only went on a train when you really had to go someplace. All the things we take for granted today were as far away from us as the sun. I know I may sound like an old rehashing-type, but those were different days.

But I did appreciate the opportunity to meet all sorts of people from all over the country. It was a great opportunity, I can tell you. There were guys from Florida, Michigan, Utah, Texas—I don’t think there was one state that wasn’t represented there. The experience helped me appreciate the variety of the country, in the people, the language, and culture. It is incredible to think that we are as diverse as we are and how we have held together as one country. Really, it is the one clear fact of this country that makes it unique to the world.

Communications were very poor back then. We had no idea where some of the places were. Some guys didn’t even know where New York was. Once I told a Texan that I was from Brooklyn and he asked me, “What’s a Brooklyn?” Those were the times when convention collided with new beginnings. I mean, the world was changing; the attitudes were changing. Movies had a tremendous role in that change. No matter what people say, we learn from what we see in the movies and read in books. Through them you began to meet different types of people and learn about different types of cultures.

I met Southerners for the first time. That was a big experience. I didn’t know anybody who spoke like that. Well, they spoke like that in the movies, but here it was live and real. I met Texans. I met people who had grown up on 40 acres of farm and never seen a person they didn’t know for years, never seen a big city, and here I was from the big city and all I ever saw was a lot of people I didn’t know. In that particular way, I think the war did a lot for uniting America; it was a galvanizing experience. It united the states because it forced people to work and live in close quarters with each other; it forced us to meet each other on common terms, but I can tell you that there were times when these meetings weren’t the happiest of meetings.

And I was right there; I was one of them. I had never seen a Texan in the flesh, the Texan had never seen somebody from New York; it was a country of people who had never met each other. I never saw a Texan until I got into a truck with one during the war. I wanted to talk to one and so I did and I can tell you that it was harder to do than I had imagined. It turned out that he had never talked to a New Yorker either; he thought we were all swells, wise guys with money to burn. Well, I corrected him on that and he was very surprised, but so was I; he had never ridden a horse in his life, he was from a big city like Houston, and he didn’t know anything about ranches—but he was still a tall man that talked like a Texan, so at least some of what I expected held true. I can’t say that about myself; I was not the stereotype of a New Yorker of the time.

The thing is that we all met.

I met people from Georgia. I found people of my own religion living in Georgia. There are a lot of Jewish people living in Savannah and there were a lot of Jewish people living in other parts of Georgia, in all parts of the South—even in Texas. I realized that there were a lot of similar people living all over the place. I began to get a feel for the United States in a way I never had before. I could envision the United States as the American flag, the stars and the stripes—the meaning of it.

..

Once I entered this village, I was sent out with my platoon to scout for Germans. I went up one corner and looked into these store windows. All of them were empty of course; the place was completely uninhabitable. It was like walking in on a movie set; I was walking around these foreign towns in full gear, full uniform in these bombed-out French cities—it was like a dream or a nightmare. Then I came to this French hotel. The front door was charred and still hanging from its hinges. It had a big winding staircase in the lobby—probably a swanky place where all the swells went to pick up girls. When I pushed the door open, I was startled by a sound from behind a pile of rubble. I was ready with my weapon and I said in German and French to come out with your hands up. I waited for a moment. Nobody answered so I got worried and I called out again; this time I was thinking that I was going to see some action.

Then this big dog came out from behind the pile. It was a great big hound that was badly injured; it was cut and burned all over. They must have blown the building when the dog was in it. It stopped in front of me and just stared. It didn’t growl or whimper, it just looked at me with these deep accusing eyes; it was the most human expression I have ever seen on an animal. It was like he was saying, “You, you did this to me!” Oh, I felt so guilty. I felt just terrible and so hurt, because to me it was like an accusation by a dumb creature that didn’t care why I was there or anything about the Germans. All he knew was that I was there and he was hurting; that’s all this animal knew. All this was happening around him and even though I had nothing to do with it, I’m still the cause. I didn’t have the courage to look this beast in the eyes any longer. I lowered my rifle and it limped past me out of the wreckage and onto the road. He kept giving me these dirty looks, terrible dirty looks. I think I stood there for several more minutes before I continued my sweep.

…

We were on patrol, constantly on patrol. On patrol you see the strangest things—things that I can tell you are beyond anything you could call normal. Once I had an old guy with a little gray beard run over to me. I can hear his thin little voice as he looked into my eyes. Tears were running down his cheek. He couldn’t believe his eyes. He blinked a couple of times and he said, “You’re Jewish.” I said, “Yeah, I’m Jewish.” So he said, “Come with me.” So I ran after this little old guy with the rest of my squad behind me. It’s a long road; I remember some farm buildings and a factory. It could have been an ambush, but we figured that it probably wasn’t—I mean, what would the Germans be doing with this little gray beard? Then we came to this walled-in place, this stockade, and he pointed. “There, there,” he said. I stopped. German guards were leaving by the dozens; I could see them jumping over the wall and getting out of there the best way they could. They knew that I am a Scout, they knew that this big division was right behind me. I was standing there looking at them as they yelled out ‘f*ck you’ in English. They all said that by that time. They thought it was a big insult, but I don’t think they really knew what the word meant.

There they went, over the side, and then my buddies and me opened up the stockades. I thought I was going to see Prisoners of War, you know, some of our guys that got caught in some of the early fighting—but what I saw would pin you to the spot like it did me. Most of these people were Polish; Polish Jews who were working in some of the nearby factories. I don’t remember if the place really had a name, it was a smaller camp—not like Auschwitz, but it was horrible just the same. Just horrible. There were mostly women and some men; they looked like they hadn’t eaten for I don’t know how long. They were scrawny. Their clothes were all tattered and dirty. The Germans didn’t give a sh*t for anything. They just left the place; just like leaving a dog behind to starve. I was standing there for a long time just watching, thinking to myself, “What do I do?” Just thinking about it makes my stomach turn. All I could say was, “Oh, God.”

http://twomorrows.com/kirby/articles/27ww2.html

I agree with the substance of this article–precisely because it IS Captain America.

Why would you sanitize the hell out of a property practically guaranteed to make most of its money in the States? Are all Americans in “LALALA ICANTHEARYOU” mode now? Well, I’m not… guess what, haven’t seen this movie yet. Doesn’t exactly scream “big screen” when they’re fighting cartoon villains like HYDRA and why would a grown person like myself want to watch “characters” with the innocence of babes?

It’s funny, race wasn’t ignored in “The Dirty Dozen,” even if–as in so many movies of the era–the black guy bought it.

Why was “The Dirty Dozen” able to look head-on at something that was closer in historical time while Captain America has wrapped wool around its eyes and ears? Even twenty years ago I feel that the attitude would have been High Audience Pander, but today it’s “Speak No Evil”.

Why?

Re: Captain America and the Holocaust, I recommend you take a look at Garth Ennis’ limited series The Unknown Solider, which does a wonderful job taking this into account, and also showing, just in general, how any human tasked with being the living embodiment of a nation-state would become deeply, deeply warped.